Spotlaw 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Plan Guntur District

SECOND FIVE YEAR PLAN DISTRICT PLAN 1956-61 GUNTUR DISTRICT PLAI^NNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT ANDHRA PRADESH PREFACE The District being the administrative unit very intimately affects the life of the people. Most people regard the headquarters of the district as the seat of administration. Ir is there that every Department has its representative who is responsible for administering the plan programme as far as it relates to his subject. It was therefore considered necessary to prepare the district segments of the State’s Second Five Year Plan which would give a broad picture of the plan program me in the district. A district plan for the Second Plan period as a whole may not be very realistic as it has got to be flexible enough to admit of changes necessary consequent on the finalisation of detailed and specific plans for each year in consultation with the various Departments of the State and the Planning Co mmission. Even so the district plan would give the frame work within which the plan will be implemented in the District. The present publication furnishes the detailed pro grammes of development works and schemes program med for execution during the Second Plan period in the District. They also include schemes that w'ould benefit a particular region or the State as a whole but which are proposed to be implemented in the district. We are conscious that this publication is capable of being improved in order to serve the needs of the public better. Suggestions for improvement are, therefote, welcome and they may be communicated to the Deputy Secretary (Planning), Government of Andhra Pradesh. -

Self Study Report

NAAC Self Study Report SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL (NAAC) Bangalore, India St. Mary’s Group of Institutions Guntur (Approved by AICTE, New Delhi & Affiliated to JNTUK, Kakinada) Chebrolu (Village & Mandal), Guntur Dt. - 522212, A.P, INDIA Tel: 08644-254477 Website: www.stmarysguntur.com St. Mary‟s Group of Institutions Guntur 1 NAAC Self Study Report St. Mary‟s Group of Institutions Guntur 2 NAAC Self Study Report INDEX S. No. Description Page No. 1 Part A (Preface / Executive Summary) 9 2 Part B (Institution Profile) 15 Criterion 1 23-42 1.1 Curriculum Planning and Implementation 24 3 1.2 Academic flexibility 32 1.3 Curriculum Enrichment 37 1.4 Feedback System 40 Criterion 2 43-88 2.1 Student Enrollment and Profile 44 2.2 Catering to Student Diversity 48 4 2.3 Teaching-Learning Process 50 2.4 Teacher Quality 59 2.5 Evaluation Process and Reforms 78 2.6 Student Performance and Learning Outcomes 81 Criterion 3 89-124 3.1 Promotion of Research 90 3.2 Resource Mobilization for Research 99 3.3 Research Facilities 101 5 3.4 Research Publications and Awards 105 3.5 Consultancy 112 3.6 Extension Activities and Institutional Social Responsibility 114 3.7Collaborations 120 Criterion 4 125-140 6 4.1 Physical Facilities 126 St. Mary‟s Group of Institutions Guntur 3 NAAC Self Study Report 4.2 Library as a Learning Resource 131 4.3 IT Infrastructure 136 4.4 Maintenance of Campus Facilities 139 Criterion 5 141-166 5.1 Student Mentoring and Support 142 7 5.2 Student Progression 158 5.3 Student Participation -

District Census Handbook, Guntur, Part XII-A & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GUNTUR PARTS XII - A &. B VILLAGE &. TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE It TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT R.P.SINGH OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1995 FOREWORD Publication of the District Census Handbooks (DCHs) was initiated after the 1951 Census and is continuing since then with .some innovations/modifications after each decennial Census. This is the most valuable district level publication brought out by the Census Organisation on behalf of each State Govt./ Uni~n Territory a~ministratio~. It Inte: alia Provides data/information on· some of the baSIC demographic and soclo-economlc characteristics and on the availability of certain important civic amenities/facilities in each village and town of the respective ~i~tricts. This pub~i~ation has thus proved to be of immense utility to the pJanners., administrators, academiCians and researchers. The scope of the .DCH was initially confined to certain important census tables on population, economic and socia-cultural aspects as also the Primary Census Abstract (PCA) of each village and town (ward wise) of the district. The DCHs published after the 1961 Census contained a descriptive account of the district, administrative statistics, census tables and Village and Town Directories including PCA. After the 1971 Census, two parts of the District Census Handbooks (Part-A comprising Village and Town Directories and Part-B com~iSing Village and Town PCA) were released in all the States and Union Territories. Th ri art (C) of the District Census Handbooks comprising administrative statistics and distric census tables, which was also to be brought out, could not be published in many States/UTs due to considerable delay in compilation of relevant material. -

District Census Handbook, Guntur, Part X

CENSUS 1971 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GUNTUR PART X-A VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY PART X-B VILLAGE & TOWN PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT T. VEDANTAM OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVER.NMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1973 The visitors include mostly the Hindus, while II lew thousand Muslims and Christians also visit the shrine, some of them with devotion and many Of them for fun. Thousands of Lambadas even from the Telan gana Region visit this famous temple on Sivaratri day who take pleasure of putting their donations in the 'hundi' box in the shape of silver rupees. Such a huge congregation is an exclusive feature of the KOlappa konda festival alone. The dark night of Mahasivaratri and the usually dreary landscape of the area throbs with life full of mirth, gay and ecstasy and reverbera tes with din and rattle that emanate from the vast concourse of people that throng in lakhs and lakhs at this holy pilgrim spot of Sri Trikuteswara Kshetram to witness and participate in the festival celebratcd once in a year. F1'(>(' feeding is done in thl' temporary sheds ((Instructed for different communities on this jl'stilJ(, occasion. While a majoritv of the Hind1lS ob.len/(' fast on this holy day, a few thousand take food in these community feasts. The highlight of the festival is the participation Kotappa Kanda of 'Prabhas' of dilJaent sizes which are made up of Kotappakonda, a hamlet of Kondaka1l11T Village bamboo and coloured cloth and paper. Many of the lies at a distance of 7 miles or 12 Kms. -

Crystal Reports

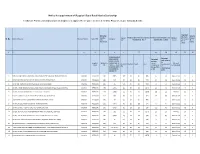

PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST SPECIAL RECRUITMENT DRIVE FOR DIFFERENTLY ABLED PERSONS, 2020-21 FILLING OF BACKLOG VACANCIES RESERVED FOR DIFFERENTLY ABLED IN VARIOUS DEPARTMENTS, GUNTUR DISTRICT Group-IV * Name of Post: 01. Junior Assistant Category: OH Qualificaon: Any Degree & Knowledge in Computer Automaon No. of Posts: General-3 * The GPA percentage in the qualifying academic examinaons has been considered as standard of merit in calculang the merit of the candidates, where the Universies have awarded the GPA in their Marks Memorandum / Provisional Cerficate. In case, if the Universies have awarded marks in lieu of GPA, the Group Marks (Part-II) have been considered as merit. Sl. Appln. Name of the Candidate Father's Name & Address Disability Sadaram Date of Age as on Gender Employment Navity Qualificaon Marks Max. % of Addional Remarks Eligible / No. No. % Cerficate Birth 01-07-2020 M / F Regd. No. Local / Gained Marks Marks Aer Scruny Qualificaon Ineligible issued Non Marks Max. % of Y / N local Gained Marks Marks 12 3 4 56 7 8 910 1112 1314151617 18 19 20 21 151PAPARAJU K PAPARAJU ANJANEYA SARMA, 90 Y 05/20/198931y, 1m, 11d M F1/2007/05201 L B.SC Computers1136 190059.7895 1137195058.3077 B.SC Computers Eligible CHAITANYA 6-178 SAIRAM TOWENSHIP NEAR MEDICAL COMPLEX SATTENAPALLI ROAD NARASARAOPET, NARASARAOPETA (R), Narasaraopet, Phone: 7702421204 258DAVALA DAVALA SOLMON RAJU, SOLASA 88 Y 06/17/199327y, 0m, 14d M F1/2012/06791 L B.A 1342 170078.9412 7.901079.0000 B.A Eligible VEERAKUMAR VILLAGE, SOLASA, Edlapadu, Phone: 9700684207 364VENKATA -

S.No. State Name State Code District Name District Code Sub District

Sub State District Village/Town S.no. State Name District Name Sub District Name District Village/Town Name Name of DA Code Code Code Code 1 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Ananthapuram 5330 A.Narayanapuramu 595096 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 2 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Penukonda 5356 Adadakulapalli 595434 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 3 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Ananthapuram 5330 Alamuru 595088 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 4 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Uravakonda 5317 Amidala 594897 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 5 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Ananthapuram 5330 Anantapur (CT) 595098 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 6 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Beluguppa 5318 Ankampalli 594908 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 7 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Bathalapalli 5337 Apparacheruvu 595170 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 8 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Beluguppa 5318 Avulenna 594910 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 9 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Bukkarayasamudram 5329 B.K.Samudram 595075 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 10 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Kothacheruvu 5346 Bandlapalle 595304 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 11 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Bathalapalli 5337 Bathalapalli 595169 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority 12 Andhra Pradesh 28 Ananthapur 553 Beluguppa 5318 Beluguppa 594905 Anantapur–Hindupur Urban Development Authority -

Sms Pharmaceuticals Limited Statement Showing the List of Share Holders

SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 1 BANK NAME :AXIS BANK LTD FOR THE YEAR :2014-2015 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. NO. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1.KUNADI SUDARSHAN REDDY 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718255 11596 KINGS COLONY ROAD GRAND BLANC MICHIGAN 2.SRI MALLIKARJUNA CHEMICALS PRIVATE LIMITED 42400.00 22-OCT-2022 718265 FLAT NO 506A ADITYA ENCLAVE NILGIRI AMEERPET HYDERABAD 500016 3.TATI SUJATHA 2000.00 22-OCT-2022 718266 7-1-28/3 AMEERPET 500016 4.RANGA RAO MALEMPATI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718267 601, SAI SRIRI SAMPADA APTS LEELA NAGAR, AMEEREPT 500016 5.MALEMPATI SAROJINI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718268 601 SAI SIRI SAMPADA APTS LEELA NAGAR, AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 6.MALLIKHARJUNA RAO DIVI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718270 7-1-215/D/1/401, YASHO CHANDRA HEAVEN, B K GUDA DHARAMKARAN ROAD, AMEERPET 500016 7.S DEVENDRA RAO 11532.00 22-OCT-2022 718271 7-1-28/1/A/12 PARK AVENU AMEERPET 500016 8.HARI K VALLURUPALLI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718275 G2, BRUNDAVAN APARTMENTS PLOT 34, CZECH COLONY, SANATNAGAR 500018 9.SAROJA DEVI VALLURUPALLI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718276 G-2 BRUNDAVAN APARTMENTS PLOT 34, CZECH COLONY, SANATH NAGAR 500018 10.SREEKIRAN VALLURUPALLI 4000.00 22-OCT-2022 718277 G-2, BRUNDAVAN APARTMENTS PLOT 34, CZECH COLONY, SANATNAGAR 500018 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PAGE TOTAL : 83932.00 CUM TOTAL : 83932.00 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 2 BANK NAME :AXIS BANK LTD FOR THE YEAR :2014-2015 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. -

Unclaimed Dividend Page : 1 Bank Name :Sbi for the Year :2015-2016 ------Slno Name/Address Amount Due Date War

SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 1 BANK NAME :SBI FOR THE YEAR :2015-2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. NO. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1.CHANDULAL G SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742738 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON SW2Q QSR, 2.RAMA C SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742739 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 3.BHARAT C SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742740 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 4.RITA B SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742741 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 5.RAMACHNADRA RAO VEMULAPALLI 180.00 23-OCT-2023 742742 3400, DORAL DRIVE WATERLOO IOVA 50701,USA 6.PRASAD RAO VDM RAVELLA 200.00 23-OCT-2023 742743 6918 N LATROBE SKOKIE ILLINOIS USA,60077 7.PRASANNA KUMAR TUMMALA 20.00 23-OCT-2023 742744 H NO 21,KAMALAPURI COLONY PHASE - 3 INDIRA NAGAR,HYDERABAD 8.JAGAN MOHAN RAO K 2.00 23-OCT-2023 742745 C/O VORIN LABORATORIES LTD , GADDAPOTHARAM VILLAGE ZINNARAM MANDAL 9.SRINIVASULU GADIKOTA 2.00 23-OCT-2023 742746 VORIN LABORATORIES LTD GADDAPOTHARAM MEDAK DIST JINNARAM MANDAL 10.VIJAYANARAYNA DEVINENI 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742747 VIJAYA NAGAR GAS COMPANY AMEERPET HYDERABAD 11.JHANSI LAKSHMI VADLAMUDI 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742748 8-3-676/1/A/2 YELLAREDDY GUDA HYDERABAD 12.KRISHNA MURTHY KORA 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742749 8-3-721/1/16/1/1 YELLAREDDY GUDA HYDERABAD ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PAGE TOTAL : 608.00 CUM TOTAL : 608.00 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 2 BANK NAME :SBI FOR THE YEAR :2015-2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. -

Sms 2015-2016

SMS_2015-2016 SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 1 BANK NAME :STATE BANK OF INDIA FOR THE YEAR :2015-2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. NO. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1.CHANDULAL G SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742738 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON SW2Q QSR, 2.RAMA C SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742739 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 3.BHARAT C SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742740 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 4.RITA B SHETH 48.00 23-OCT-2023 742741 24,HOOD ROAD WIMBLEDON LONDON,SW2Q QSR 5.RAMACHNADRA RAO VEMULAPALLI 180.00 23-OCT-2023 742742 3400, DORAL DRIVE WATERLOO IOVA 50701,USA 6.PRASAD RAO VDM RAVELLA 200.00 23-OCT-2023 742743 6918 N LATROBE SKOKIE ILLINOIS USA,60077 7.PRASANNA KUMAR TUMMALA 20.00 23-OCT-2023 742744 H NO 21,KAMALAPURI COLONY PHASE - 3 INDIRA NAGAR,HYDERABAD 8.JAGAN MOHAN RAO K 2.00 23-OCT-2023 742745 C/O VORIN LABORATORIES LTD , GADDAPOTHARAM VILLAGE ZINNARAM MANDAL 9.SRINIVASULU GADIKOTA 2.00 23-OCT-2023 742746 VORIN LABORATORIES LTD GADDAPOTHARAM MEDAK DIST JINNARAM MANDAL 10.VIJAYANARAYNA DEVINENI 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742747 VIJAYA NAGAR GAS COMPANY AMEERPET HYDERABAD 11.JHANSI LAKSHMI VADLAMUDI 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742748 8-3-676/1/A/2 YELLAREDDY GUDA HYDERABAD 12.KRISHNA MURTHY KORA 4.00 23-OCT-2023 742749 8-3-721/1/16/1/1 YELLAREDDY GUDA HYDERABAD ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PAGE TOTAL : 608.00 CUM TOTAL : 608.00 Page 1 SMS_2015-2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SMS PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT SHOWING THE LIST OF SHARE HOLDERS - UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND PAGE : 2 BANK NAME :STATE BANK OF INDIA FOR THE YEAR :2015-2016 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SLNO NAME/ADDRESS AMOUNT DUE DATE WAR. -

Andhra Pradesh(392

Details in subsequent pages are as on 01/04/12 For information only. In case of any discrepancy, the official records prevail. DETAILS OF THE DEALERSHIP OF HPCL TO BE UPLOADED IN THE PORTAL Zone: SOUTH CENTRAL ZONE STATE: ANDHRA PRADESH Dealership address (incl. location, Name(s) of SR. No. Regional Office State Name of dealership outlet Telephone No. Dist, State, PIN) Proprietor/Partner(s) SY. NO. 1299, BANDAPALLI,NATIONAL HIGHWAY-18, KURNOOL-CHITTOOR 1 KADAPA RO AP MS/HSD SIVA SAI PETRO HUB SIVA PRASAD REDDY 9701999119 RD,RAYACHOTY MANDAL,CUDDAPAH DISTRICT-516003,A.P. HPCL DEALERS,SURVEY NO. 917/1B , MS/HSD SRI VEERABADRA FILLING KAMALAPURAM VILLAGE,SH-31, 2 KADAPA RO AP P. ANKI REDDY 9848356219 STATION KAMALAPURAM MANADAL,CUDDAPAH DISTRICT-516289,A.P. HPCL DEALERS,NAGARI VILLAGE AND P.T.LATHA,CHITTOOR 3 KADAPA RO AP SRI KRISHNA FUELS 9704256782 MANDAL,NAGARI, DISTRICT,A.P. DNO.5/54 & 5/55,KOTHACHERUVU 4 KADAPA RO AP SRI MASTANAPPA QULITY FUELS VILLAGE & MANDAL,ANANTAPUR P VENKATESH 94916-21600 DISTRICT-515133,A.P. SURVEY NO.90,KANEKAL-BELLARY ADHOC-SRI LAKSHMI VENKATESWARA M VENUGOPAL &P 5 KADAPA RO AP ROAD,BOMMANAHAL VILL- 94407-52808 FUELS SATYANARAYANA 515871,ANANTAPUR DIST, A.P. HPC DEALERS,KOTHPALLI VILLAGE, MUDUKURU 6 KADAPA RO AP AJAY FILLING STATION K.SUBBA RAO 9290011330 ROAD,PRODDUTUR,CUDDAPAH DIST- 5163161,A.P. HPCL 7 KADAPA RO AP AMBATI SUBBARAYADU AND BROS DEALERS,PULIVENDULA,PULIVENDULA A.SUBBARAYADU 9949643219 (P),CUDDAPAH DIST-516329,A.P. HPC DEALERS,SY.NO.345/2,ANANTAPUR 8 KADAPA RO AP ARMILI FILLING STATION S PUSHPALATHA 94413-60959 ROAD, KALYANDURG,ANANTAPUR DIST-515761,A.P. -

Canara Bank(400)

Department of Supervision Branch Audit Allocation Report Branch Audit - 2020-2021 Canara Bank(400) No. of Sr. No UCN Firm Name and Branches Branch District State Address allocated Name A A A M & CO 1 333570 A-58 IST FLOOR 3 SECTOR-65 ALIGARH KELANAGAR Aligarh Uttar Pradesh ALIGARH MAIN Aligarh Uttar Pradesh NOIDA INDUSTRIAL Gautam Buddha FINANCE Nagar Uttar Pradesh BRANCH A A JANAWADE & CO FLAT NO 606 A WING AISHARYAM COMFORT, 2 1000006 NR ADOR WELDING 3 COMPANY KHANDOBAMAL AKURDI PUNE KARVE Maharashtra ROAD II Pune PUNE KIRKEE Maharashtra BAZAAR Pune PUNE MODEL Maharashtra COLONY Pune A A S A AND ASSOCIATES 3 260138 SBI ATM BUILDING IST 3 FLOOR, UDIT NAGAR BANGALORE JAYANAGAR Bangalore Karnataka SHOPPING Urban COMPLEX BANGALORE LAVELLE Bangalore Karnataka ROAD Urban BANGALORE, Bangalore HSR LAYOUT Urban Karnataka A A SINGH & CO HARMONY ARCADE 4 333555 CHAMBER NO 19-20, 3 17/1 TELEGRAPH ROAD THE MALL BACHGAON Firozabad Uttar Pradesh Mahamaya CHITTUPUR Nagar Uttar Pradesh SHYAMPUR Fatehpur Uttar Pradesh A A SOLAO & CO 5 891444 PLOT NO 8 SURVE 3 NAGAR GITTIKHADA Nagpur Maharashtra N 1 Generated On 21-Jul-2021 LAW COLLEGE SQUARE, Nagpur Maharashtra NAGPUR WADI Nagpur Maharashtra A A VIRANI & ASSOCIATES HOUSE NO Y 8 6 1003133 RAMNATH CITY, 3 KORADI ROAD BOKHARA GANDHIBAG, NAGPUR Nagpur Maharashtra KALMESHWA R Nagpur Maharashtra NAGPUR KHAMLA Nagpur Maharashtra A ANAND & CO NEAR DR.P K DAS CIVIL 7 334687 LINES, NEAR HOTEL 3 RAJ MAHEL RETAIL ASSETS HUB Moradabad Uttar Pradesh MORADABAD SPECIALISED SME BRANCH, Moradabad Uttar Pradesh MAJHOLA -

AP H2 FINAL .Xlsx

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Andhra Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee / Estimated Security Minimum monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Finance to be arranged by the Mode of Deposit Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Bid amount Sl. No Sales Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * applicant (Rs. in Lakhs) selection (Rs. in (Rs. in Potential # Lakhs) Lakhs) 12 345678 9a9b101112 SC/SC CC-1/SC CC- Estimated 2/SC PH/ST/ST Estimated fund required CC-1/ST CC-2/ST working for Regular / MS+HSD in PH/OBC/OBC CC- capital (Draw of (CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area development Rural Kls 1/OBC CC-2/OBC requirement Lots/Bidding) FS) of PH/OPEN/OPEN for operation infrastructure CC-1/OPEN CC- of RO at RO 2/OPEN PH 1 WITH IN 6 KMS FROM G KONDURU, ON G KONDURU TO GANGINENI ROAD(NOT ON NH) KRISHNA REGULAR 100 OPEN DC 30 30 900 25 60 Draw of Lots 15 5 2 KONATHAMATMAKUR VILLAGE, ON DAMULURU TO VATSAVAI ROAD KRISHNA REGULAR 100 OBC DC 30 30 900 25 60 Draw of Lots 15 4 3 ON SH 192, MAKKAPETA, ON CHILLAKALLU TO VATSAVAI ROAD KRISHNA REGULAR 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 4 ON RHS , FROM IBRAHIMPATNAM CROSS ROAD TO ANUMANCHIPALLI VILLAGE ON NH 65 KRISHNA REGULAR 150 OPEN DC 35 45 1575 25 75 Draw of Lots 15 5 5 ON RHS, FROM KAMBHAMPADU TO A KONDURU ON NH-30 KRISHNA REGULAR 150 OPEN CC 35 45 1575 25 10 Bidding 30 5 6 POLICE CONTROL ROOM TO KAY HOTEL (ELURU ROAD), VIJAYAWADA KRISHNA REGULAR 250 OBC DC 18 18