The Polish Immigrant Experience in Britain 1. Polish Migration to Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naród Polski Bi-Lingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America a Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities

Naród Polski Bi-lingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America A Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities June 2018 - Czerwiec 2018 No. 6 - Vol. CXXXIII www.PRCUA.org President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda and First Lady Agata Kornhauser-Duda Make a Historic Visit to the PRCUA/PMA Headquarters Zapraszamy do czytania stron 19-24 w j`z. polskim. President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda and First Lady Agata Kornhauser-Duda with invited guests at the PMA’s Great Hall (photo: J. Siegel) Chicago, IL - Gallery and the Sabina The Polish Museum P. Logisz Great Hall, of America and the where they met with a Polish Roman group of invited guests. Catholic Union of Present were members America were of the PMA Board of honored to welcome Directors, President of the representatives from Republic of Poland various Polish Andrzej Duda and American organi- First Lady Agata zations, political Kornhauser-Duda to representatives, and the their headquarters on PMA’s staff. Poland’s Presidential Couple welcomed by PRCUA V.P. Jaminski presenting the PRCUA history in the Friday, May 18, President and First President Drobot and PMA President Owsiany Board Room 2018. Lady Duda signed the (photo: Facebook - Consulate General of Poland) (photo: Facebook - Consulate General of Poland) The Presidential PMA Guest Book and couple visited Chicago on May 18-19 during their recent trip to the United presented the PMA with the flag of the Republic of Poland, which was States. This was President Duda’s first trip to Chicago since his election as gratefully accepted by PMA President Richard Owsiany. -

Polish Air Forces in France and Great Britain 1 Polish Air Forces in France and Great Britain

Polish Air Forces in France and Great Britain 1 Polish Air Forces in France and Great Britain Polish Air Forces in France and Great Britain Founded 18 May 1940 Country United Kingdom, France Allegiance Polish government-in-exile Insignia Identification symbol Fin flash Aircraft flown Attack Caudron C.714, Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire The Polish Air Forces (Polskie Siły Powietrzne) was the name of the Polish Air Forces formed in France and the United Kingdom during World War II. The core of the Polish air units fighting alongside the Allies were experienced veterans of the 1939 Invasion of Poland. They contributed to the Allied victory in the Battle of Britain and most World War II air operations. A total of 145 Polish fighter pilots served in the RAF during the Battle of Britain, making up the largest non-British contribution.[1] By the end of the war, around 19,400 Poles were serving in the RAF.[2] History After the joint German-Soviet victory in the Invasion of Poland of 1939, most of the flying personnel and technicians of the Polish Air Force were evacuated to Romania and Hungary, after which thousands found their way to France. There, in accordance with the Franco-Polish Military Alliance of 1921 and the amendments of 1939, Polish Air Force units were to be re-created. However, the French headquarters was hesitant about creating large Polish air units, and instead most Polish pilots were attached to small units, so-called keys. Only one large unit was formed, the Groupe de Chasse polonaise I/145 stationed at Mions airfield. -

We Shall Remember Them…

We Shall Remember Them… The Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum – PISM (Instytut Polski i Muzeum imienia generała Sikorskiego – IPMS) houses thousands of documents and photographs, as well as museum artifacts, films and audio recordings, which reflect the history of Poland. Materials that relate to the Polish Air Force in Great Britain form part of the collection. This presentation was prepared in May/June 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic when the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum was closed due to lockdown. The materials shown are those that were available to the authors, remotely. • The Battle of Britain lasted from the 10th July until the 31st October 1940. • This site reflects on the contribution and sacrifice made by Polish airmen during those three months and three weeks as they and pilots from many other nationalities, helped the RAF in their defence of the United Kingdom. The first exhibit that one sees on entering the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum is this sculpture. It commemorates the contribution of the Polish Air Force during the second world war and incorporates all the Polish squadrons’ emblems and the aircraft types in which they fought.. In the Beginning….. • The Polish Air Force was created in 1918 and almost immediately saw action against the invading Soviet Army during the Polish-Russian war of 1920. • In 1919 eight American volunteers, including Major Cedric Fauntleroy and Captain Merian Cooper, arrived in Poland and joined the 7th Fighter Squadron which was renamed the “Kosciuszko Squadron” after the 18th century Polish and American patriot. When the 1920-21 war ended, the squadron’s name and traditions were maintained and it was the 111th “Kościuszko” Fighter Escadrille that fought in September 1939 over the skies of Poland. -

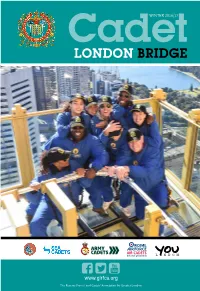

London Bridge

CadetWINTER 2016/17 LONDON BRIDGE www.glrfca.org The Reserve Forces’ and Cadets’ Association for Greater London © Sandra Rowse Lord Mayor’s Show Cadets from across the capital and beyond Both Sea Cadets and Air Cadets London Area Bands were on took part in the 801st Lord Mayor’s Show in hand with rousing music to warm the spirits as well as the Boys’ November, braving early torrential downpours and Girls’ Brigade Bugle Band and two Scout and Guide Bands. to bring smiles to the faces of hardy With the rain easing off as the parade got going, the smiles Londoners lining the streets of the City. in the photographs prove everyone had a great time. © Sandra Rowse © Sandra Rowse The best article in Cadet London Bridge submitted Front Cover: ACF Cadets and Adult Instructors from Middlesex & NW London and SE London £100 by a unit or individual will receive £100. sectors enjoying the Sydney Tower Skywalk. The star article for this issue can be found on p17. For full story see page 12. 2 CADET LONDON BRIDGE WINTER 2016/17 Remembrance Day Cadets from all over London were out in force in the run up to Remembrance Day, helping to collect for the Poppy Appeal, attending the Westminster Abbey Field of Remembrance and joining local residents in acts of remembrance throughout London. Photo: Andrew Dunsmore Photo: Andrew Dunsmore Cadets support Remember WW1 Awards Lord-Lieutenant’s Cadet RSM Khalil Ahmad, 192 Heston ACF and Cadet Chloe Edwards, 56 (Woolwich) ATC were on hand at the Army & Navy Club on 2nd November to welcome guests to the Remember WW1 Awards. -

Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Management Plan 2016 - 2026

Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Management Plan 2016-2026 Green Spaces Team Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Management Plan 2016 - 2026 Contents Page 1. Site summary and description 3 2. Site details: location, access, maps 4 History 8 Ecology 9 3. Visions for Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden11 13 4. Site aims and objectives 13 4.1. Create and maintain a welcoming site. 14 4.2. Ensure that the site is healthy safe and secure 15 4.3. Ensure that the site is clean and well maintained. 16 4.4. Ensure sustainable management of resources. 17 4.5. Appropriate management of conservation features 18 4.6. Encourage community involvement 20 4.7. Ensure effective marketing 21 5. Management Actions and Maintenance Plan 23 Appendices 26 Appendix 1: Introduction to the London Borough of Hillingdon 27 Appendix 2: Green Spaces team structure 29 Appendix 3: Summary of grounds maintenance 30 2 Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Management Plan 2016 - 2026 1. Site summary Details Site Name Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Address (Main Entrance) West End Road, South Rusilip Postcode HA4 6QX Grid Reference TQ 110 845 Ownership London Borough of Hillingdon Name of Lead Officer Dragana Knezevic Lead Officer’s contact details Postal: Green Spaces Team Civic Centre 4W/08 High St, Uxbridge Middlesex, UB8 1UW Phone: 01895 277 534 Email:[email protected] Date site acquired 1953 PPG17 designation Open space London Parks typology designation Open space Access points West End Road, South Rusilip Public Transport Busses: E7, 696 Key features Key habitats Native hedge, Scrubland Wildlife Meadow, Amenity Grassland Ponds Horticultural features Box hedge Flower beds Trees Other designations Greenbelt Conservation Area Listed Grade II Tree preservation orders No 3 Polish War Memorial Remembrance Garden Management Plan 2016 - 2026 Description This memorial garden is dedicated to the Polish Air Force by the London Borough of Hillingdon. -

Stones Used in the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire

Urban Geology in the English Midlands No. 4 Stones used in the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire Ruth Siddall The Armed Forces Memorial; Portland Stone The National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas has become established as a garden of National Remembrance, with almost 400 memorials and thousands of commemorative trees (with new ones added every year) which commemorate Her Majesty’s Armed Forces who have served in military campaigns since the start of the 20th Century. Civilian organisations are also represented. These include the Emergency Services and other civilian services, organisations, charities and groups who have served the nation from the UK or the Commonwealth. Other memorials commemorate individuals or groups who have achieved recognition for their service or sacrifice. The site was conceived in the mid 1990s by Royal Navy Commander David Childs CBE and Group Captain Leonard Cheshire who were partly inspired the Arlington National Cemetery in the USA, believing that the UK lacked a single place for national remembrance (Bowdler, 2021; Williams 2014, Gough, 2009). However, unlike Arlington, this is not a cemetery, it is a ‘cenotaphic memorial landscape’ and one not just dedicated to the remembrance of troops and civilians lost in wars (Williams, 2014). The only burials here date to the Bronze Age; several barrows are located on the site (NMA, 2017, Williams, 2014). Land was donated by Lafarge Tarmac Aggregates Ltd., much of the 150 acre site was formally a gravel pit working the glacial river gravels of the Rivers Trent and Tame (the Arboretum is still surrounded by gravel pits today). The area was landscaped and the first trees were planted in 1997. -

1062255 November 2008 No. 39 ISSN: 1745

Bulletin November 2008 No. 39 ISSN: 1745 7556 Reg. Charity No.: 1062255 War Memorials Trust works to protect and conserve all war memorials within the UK Objectives of War Memorials Trust 1. To monitor the condition of war memorials and to encourage protection and conservation when appropriate. Bulletin 2. To provide expert advice to those involved in war memorial ISSN: 1745-7556; Published quarterly by projects and to facilitate conservation through grant schemes for war memorial projects. War Memorials Trust 4 Lower Belgrave Street 3. To work with relevant organisations to encourage their London SW1W 0LA accepting responsibility for war memorials and recognising Telephone charity: 020 7259 0403 the need to undertake repair and restoration work to these Telephone conservation: 020 7881 0862 monuments as required. Fax: 020 7259 0296 Email: [email protected] Web: www.warmemorials.org 4. To build a greater understanding of war memorial heritage and raise awareness of the issues surrounding war memorial Registered Charity Number: 1062255 conservation. Patron HRH The Duchess of Cornwall Membership Rates President Winston S. Churchill War Memorials Trust Membership Rates are: Area Vice Patrons Diana Graves (England), £20 Annual Member; Sara Jones CBE (England), £30 Joint Annual Member and Maj. Gen. the Rev Llewellyn CB OBE (Wales), £100 for a Lifetime Subscription. Admiral Roger Lockwood (Scotland), The Lord Molyneaux of Killead KBE PC (N. I.), The Earl Nelson (England), Photo credits: Front cover: Simon Weston OBE (Wales). Portland war memorial (WM753) © Chris Moreton, RV Trustees J. G. Cluff (Chairman), Roger Bardell (Treasurer), War Memorials Colin Amery, Trust gratefully Winston S. Churchill, acknowledges The Lord Cope of Berkeley, the support of Jane Furlong, The Pilgrim Trust and English Heritage with its Meg Hillier MP, Conservation Programme. -

The Nation's Brightest and Noblest

The Nation’s Brightest and Noblest Narrative Identity and Empowering Accounts of the Ukrainian Intelligentsia in Post-1991 L’viv Eleonora Narvselius Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 488 Linköping University, Department of Social and Welfare Studies Linköping 2009 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 488 At the Faculty of Arts and Science at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Department of Social and Welfare Studies. Distribution: Department of Social and Welfare Studies Linköping University 581 83 Linköping Eleonora Narvselius The Nation’s Brightest and Noblest: Narrative Identity and Empowering Accounts of the Ukrainian Intelligentsia in Post- 1991 L’viv ISBN: 978-91-7393-578-4 ISSN 0282-9800 ©Eleonora Narvselius Department of Social and Welfare Studies 2009 Cover: Viktoria Mishchenko Printed by LiU-Tryck, Linköping, Sweden Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………...1 Note on Transliteration and Translation……………………………………...5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 1. Orientation, Profile and Methodological Premises of the Study 1.1. What the research is about: aims, research questions, and actuality of the study………………………………………………………….11 1.2. Orientation of the study, orientation of the researcher: preliminary notes …………………………………………………………….14 1.3. Sources and methods of material collection……………………………..22 1.4. Narrative analysis, frame analysis, and ethnographic analysis…………..26 Chapter 2. The Research Field: Multiethnic, Multicultural, Nationalist Daily L’viv 2.1. L’viv: an (un)usual borderline city………………………………….......33 2.2. The ‘most Ukrainian, least Sovietized’ city in Ukraine………………….36 2.3. -

Not Forgotten a Review of London's War Memorials July 2009

Planning and Housing Committee Not forgotten A review of London's war memorials July 2009 Planning and Housing Committee Not forgotten A review of London's war memorials July 2009 Copyright Greater London Authority July 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978-1-84781-283-4 This publication is printed on recycled paper Cover photograph credit Paul Watling Planning and Housing Committee Members Jenny Jones Green, Chair Nicky Gavron Labour, Deputy Chair Tony Arbour Conservative Gareth Bacon Conservative Andrew Boff Conservative Steve O'Connell Conservative Navin Shah Labour Mike Tuffrey Liberal Democrat On 2 December 2008 the Planning and Housing Committee agreed that Tony Arbour AM should act as a rapporteur to carry out a review of war memorials in London. The review’s terms of reference were: • To highlight the nature of the risks to London’s war memorials; • To clarify who is responsible for the war memorials’ maintenance, review relevant guidance and resources available for the task; • To assess whether further protection under the Mayor’s planning powers is appropriate. Further information about the Committee can be found at: http://www.london.gov.uk/assembly/scrutiny/planning.jsp Assembly Secretariat contacts Paul Watling, Scrutiny Manager 020 7983 4393 [email protected] Dale Langford, Committee Administrator 020 7983 4415 [email protected] Dana Gavin, Communications Manager 020 7983 4603 [email protected] Michael Walker, Administrative Officer 020 7983 4525 [email protected] 6 Contents Rapporteur’s foreword 9 1. -

Polish Airmen in the Battle of Britain. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military

REVIEWS (it being one minor part of a battle that has, itself, been overlooked). Atter does, however, claim a greater significance for the volume than it perhaps warrants. He argues that the book challenges the historiography of the battle, which has been critical of the New Army divisions generally (including 8/Lincolns), claiming that they were routed or ‘bolted’ from the battlefield. Atter believes that this is incorrect and defends the battalion from such a calumny. While some historians have made broad comments to this effect, it must be stated that my work on Loos (Loos 1915, published in 2006), which examines the experience of the reserve divisions in detail, does not come to this conclusion. It defended the performance of these units and argued that the idea of a ‘wild panic’ from the battlefield was ‘unlikely’. But Atter does not cite this, which is surprising. In the Shadow of Bois Hugo is an interesting account, written by someone with a deep attachment to the subject, but ultimately it will be of interest only to specialists in the field or those with a specific connection to the Lincolns. NICK LLOYD King's College London at the Joint Services Command and Staff College Defence Academy of the United Kingdom DOI: https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.bjmh.v5i1.829 Peter Sikora, The Polish ‘Few’: Polish Airmen in the Battle of Britain. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2018. xvii + pp. 574. ISBN: 978-1526-714855. Price £30.00. Peter Sikora’s study of the Polish ‘few’ begins not in 1940 but with a more contemporary story. -

West London Sub Regional Transport Plan

West London Contents 1. Introduction 2. Context 3. Progress report 4. Update on the transport challenges 5. Responding to the challenges: beyond the TfL Business Plan 6. Funding and delivery 7. Summary Appendices 2 1. Introduction 3 1. Introduction Publication of the sub-regional transport Ensuring the benefits of High Speed 2 are the latest sub-regional transport modelling plans (SRTPs) in November 2010 reflected Fourthly, the addendum also allows progress realised through a new strategic interchange which TfL has undertaken are also significant collaboration and joint work made across the west sub-region eg through at Old Oak Common will be essential if incorporated. All this has allowed us to between TfL boroughs, sub-regional borough Local Implementation Plans and businesses and residents in the region are to update our understanding of the outstanding partnerships, business organisations and through the sub-regional panels, to be taken fully benefit from this. transport challenges facing the west sub- London Councils as well as a range of other account of. region and to refresh our view as to how to stakeholders. West London is home to a number of major these could best be met. Over the past year there have been some development areas: Southall, Heathrow, Old It is now just over a year since the plans notable successes for London’s transport Oak, White City and Earl’s Court. The It is for the sub-regional panel, to discuss this were published. The sub-regional process is system, many of them on the national and concentration of several Opportunity Areas in draft update and agree the next steps. -

Green Flag Award Winners 2020

Green Flag Award Winners 2020 East Midlands Green Flag Award 134 winners Park Title Managing Organisation Belper Cemetery Amber Valley Borough Council Belper Parks Amber Valley Borough Council Belper River Gardens Amber Valley Borough Council Crays Hill Recreation Ground Amber Valley Borough Council Crossley Park Amber Valley Borough Council Heanor Memorial Park Amber Valley Borough Council Pennytown Ponds Local Nature Reserve Amber Valley Borough Council Riddings Park Amber Valley Borough Council Ampthill Great Park Ampthill Town Council Rutland Water Anglian Water Services Ltd Ashby de la Zouth Bath Grounds Ashby de la Zouch Town Council Brierley Forest Park Ashfield District Council Kingsway Park Ashfield District Council Lawn Pleasure Grounds Ashfield District Council Portland Park Ashfield District Council Selston Golf Course Ashfield District Council Titchfield Park Hucknall Ashfield District Council Kings Park Bassetlaw District Council The Canch (Memorial Gardens) Bassetlaw District Council Belper Memorial Gardens Belper Town Council A Place To Grow Blaby District Council Glen Parva and Glen Hills Local Nature Reserves Blaby District Council Bramcote Hills Park Broxtowe Borough Council Colliers Wood Broxtowe Borough Council Chesterfield Canal (Kiveton Park to West Stockwith) Canal & River Trust Erewash Canal Canal & River Trust Nottingham and Beeston Canal Canal & River Trust Queen’s Park Charnwood Borough Council Chesterfield Crematorium Chesterfield Borough Council Eastwood Park Chesterfield Borough Council Holmebrook Valley