Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Tanzania in Figures

2019 Tanzania in Figures The United Republic of Tanzania 2019 TANZANIA IN FIGURES National Bureau of Statistics Dodoma June 2020 H. E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli President of the United Republic of Tanzania “Statistics are very vital in the development of any country particularly when they are of good quality since they enable government to understand the needs of its people, set goals and formulate development programmes and monitor their implementation” H.E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli the President of the United Republic of Tanzania at the foundation stone-laying ceremony for the new NBS offices in Dodoma December, 2017. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical information is very important as it helps a person to do things in an organizational way with greater precision unlike when one does not have. In my business, for example, statistics help me know where I can get raw materials, get to know the number of my customers and help me prepare products accordingly. Indeed, the numbers show the trend of my business which allows me to predict the future. My customers are both locals and foreigners who yearly visit the region. In June every year, I gather information from various institutions which receive foreign visitors here in Dodoma. With estimated number of visitors in hand, it gives me ample time to prepare products for my clients’ satisfaction. In terms of my daily life, Statistics help me in understanding my daily household needs hence make proper expenditures.” Mr. Kulwa James Zimba, Artist, Sixth street Dodoma.”. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical Data is useful for development at family as well as national level because without statistics one cannot plan and implement development plans properly. -

National Environment Management Council (Nemc)

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT COUNCIL (NEMC) NOTICE TO COLLECT APPROVED AND SIGNED ENVIRONMENTAL CERTIFICATES Section 81 of the Environment Management Act, 2004 stipulates that any person, being a proponent or a developer of a project or undertaking of a type specified in Third Schedule, to which Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is required to be made by the law governing such project or undertaking or in the absence of such law, by regulation made by the Minister, shall undertake or cause to be undertaken, at his own cost an environmental impact assessment study. The Environmental Management Act, (2004) requires also that upon completion of the review of the report, the National Environment Management Council (NEMC) shall submit recommendations to the Minister for approval and issuance of certificate. The approved and signed certificates are returned to NEMC to formalize their registration into the database before handing over to the Developers. Therefore, the National Environment Management Council (NEMC) is inviting proponents/developers to collect their approved and signed certificates in the categories of Environmental Impact Assessment, Environmental Audit, Variation and Transfer of Certificates, as well as Provisional Environmental Clearance. These Certificates can be picked at NEMC’s Head office at Plot No. 28, 29 &30-35 Regent Street, Mikocheni Announced by: Director General, National Environment Management Council (NEMC), Plot No. 28, 29 &30-35 Regent Street, P.O. Box 63154, Dar es Salaam. Telephone: +255 22 2774889, Direct line: +255 22 2774852 Mobile: 0713 608930/ 0692108566 Fax: +255 22 2774901, Email: [email protected] No Project Title and Location Developer 1. Construction of 8 storey Plus Mezzanine Al Rais Development Commercial/Residential Building at plot no 8 block Company Ltd, 67, Ukombozi Mtaa in Jangwani Ward, Ilala P.O. -

Mwanza Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report For

LVWATSAN – Mwanza Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report for Construction and Operation of a Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant in Lamadi Town, Busega District, Simiyu Region – Tanzania Prepared for: Mwanza Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Authority (MWAUWASA) P.O. Box 317 Makongoro Road, Mwanza Prepared by: Mott MacDonald in association with UWP Consulting On behalf of ESIA Study Team: Wandert Benthem (Registered Environmental Expert), Mwanza Tel.: 0763011180; Email: [email protected] Submitted to: NEMC Lake Zone P.O. Box 11045 Maji Igogo, Mwanza Tel.: 0282502684 Email: [email protected] March 2017 LVWATSAN – Mwanza Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report for Construction and Operation of a Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant in Lamadi Town, Busega District, Simiyu Region – Tanzania March 2017 Mwanza Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Authority (MWAUWASA) OPS/ASD/Technical Assistance Unit (TAU), 100 boulevard Konrad Adenauer, L-2950 Luxembourg The technical assistance operation is financed by the European Union under the Cotonou Agreement, through the European Development Fund (EDF). The EDF is the main instrument funded by the EU Member States for providing Community aid for development cooperation in the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the Overseas Countries and Territories. The authors take full responsibility for the contents of this report. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the view of the European Union or the European Investment Bank. Mott MacDonald, Demeter House, Station Road, Cambridge CB1 2RS, United Kingdom T +44 (0)1223 463500 F +44 (0)1223 461007 W www.mottmac.com Green corner – Save a tree today! Mott MacDonald is committed to integrating sustainability into our operational practices and culture. -

Supervisory Committee

Costs and Benefits of Nature-Based Tourism to Conservation and Communities in the Serengeti Ecosystem by Masuruli Baker Masuruli BSc. Sokoine University of Agriculture, 1993 MSc. University of Kent, 1997 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geography Masuruli Baker Masuruli, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Costs and Benefits of Nature-Based Tourism to Conservation and Communities in the Serengeti Ecosystem by Masuruli Baker Masuruli BSc. Sokoine University of Agriculture, 1993 MSc. University of Kent, 1997 Supervisory Committee Dr. Philip Dearden (Department of Geography) Co-Supervisor Dr. Rick Rollins (Department of Geography) Co-Supervisor Dr. Leslie King (Department of Geography) Departmental Member Dr. Ana Maria Peredo (Peter B. Gustavson School of Business, University of Victoria) Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Philip Dearden (Department of Geography) Co-Supervisor Dr. Rick Rollins (Department of Geography) Co-Supervisor Dr. Leslie King (Department of Geography) Departmental Member Dr. Ana Maria Peredo (Peter B. Gustavson School of Business, University of Victoria) Outside Member People visit protected areas (PAs) for enjoyment and appreciation of nature. However, tourism that is not well planned and managed can significantly degrade the environment, and impact negatively on nearby communities. Of further concern is the distribution of the costs and benefits of nature-based tourism (NBT) in PAs, with some communities experiencing proportionally more benefits, while other communities experience more of the cost. -

AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( E Nzara Il ILEMI TRIANGLE N N

!( !( !( )"" !( ! Omo AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( e Nzara il ILEMI TRIANGLE N n Banzali Asa Yambio i ! ! !( a t n u ETHIOPIA o !( !( SNNP M Camp 15 WESTERN ( l !( EQUATORIA e !( b e Torit Keyala Lobira Digba J !( !( Nadapal ! l !( ± e r Lainya h a ! !Yakuluku !( Diagbe B Malingindu Bangoie ! !( ! Duru EASTERN ! Chukudum Lokitaung EQUATORIA !( Napopo Ukwa Lokichokio ! ! !( Banda ! Kpelememe SOUTH SUDAN ! Bili Bangadi ! ! Magwi Yei !( Tikadzi ! CENTRAL Ikotos EQUATORIA !( Ango !( Bwendi !( Moli Dakwa ! ! ! Nambili Epi ! ! ! Kumbo Longo !( !Mangombo !Ngilima ! Kajo Keji Magombo !( Kurukwata ! Manzi ! ! Aba Lake Roa !( ! Wando Turkana Uda ! ! Bendele Manziga ! ! ! Djabir Kakuma Apoka !( !( Uele !( MARSABIT Faradje Niangara Gangara Morobo Kapedo !( ! !( !( Dikumba Dramba ! Dingila Bambili Guma ! Moyo !( !( ! Ali !( Dungu ! Wando ! Mokombo Gata Okondo ! ! ! !( Nimule !( Madi-Opel Bandia Amadi !( ! ! Makilimbo Denge Karenga ! ! Laropi !( !( !( LEGEND Mbuma Malengoya Ndoa !( Kalokol ! ! Angodia Mangada ! Duku ile Nimule Kaabong !( ! ! ! ! Kaya N Dembia ert !( Po Kumuka Alb Padibe ! Gubeli ! Tadu Yumbe !( Bambesa ! Wauwa Bumva !( !( Locations Bima !( ! Tapili ! Monietu ! !( ! Dili Lodonga " ! Koboko " Capital city Dingba Bibi Adi !( !( Orom ) ! Midi-midi ! ! !( Bima Ganga Likandi Digili ! Adjumani ! ! ! ! Gabu Todro Namokora Loyoro TURKANA Major city ! Tora Nzoro ! !( !( ! ! !( Lagbo Oleba Kitgum Other city Mabangana Tibo Wamba-moke Okodongwe ! Oria !( !( ! ! ! ! ! Omugo Kitgum-Matidi Kana Omiya Anyima !( ! !( Atiak Agameto Makongo -

Tanzania & Kenya Luxury Safari

Tanzania & Kenya Luxury Safari Please note that all of the itineraries listed in our web site are actual private tour itineraries we have prepared for clients over the past 12-18 months. By the very nature of what we do, each private tour itinerary is custom, exclusive and unique unto itself. Our over-riding goal is to create lifelong memories that you and your family will forever carry deep within your hearts. Overview Though South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Rwanda, and Zambia may be our favorite high-touch safari destinations over the past few years, we certainly cannot overlook the uniqueness of Tanzania’s Ngorongoro and Serengeti wildlife areas. There is no roughing it here as the 5-star Sanctuary Swala Camp, Ngorongoro Crater Lodge, Singita Sabora Tented Camp, and Singita Faru Faru Lodge all offer a custom luxury experience. The flagship wildlife feature of Ngorongoro is the Ngorongoro Crater, home to over 250,00 animals, including the “Big 5”. Complimenting Ngorongoro is the iconic Serengeti National Park and the Mara River in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, where, though becoming increasingly less predictable, two million wildebeests usually pass through from mid-June to August. For our clients passionate about hiking, we may offer a seven-day ascent up Mt. Kilimanjaro via the Machame Route offering the challenge of a lifetime, but much rewarded by a relaxing, luxury safari experience after! Best Travel Time: Spring Summer TANZANIA TANZANIA Seven-Day Ascent up Mt. Temperature Range Temperature Range Kilimanjaro Highs: Low 90’s Highs: Low 80’s Climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro via Lows: Mid 60’s Lows: Mid 50’s the Machame Route Area Area As the highest mountain in Africa, 945,087 SQ KM 582,646 SQ KM with its summit being approximately 364,900 SQ MILES 224,961 SQ MILES 16,100 feet from its base and Population Population 19,341 feet above sea level, it is no 55.5 Million 48.5 Million wonder why bucket lists of avid Language Language climbers and hikers worldwide Swahili & English Swahili & English feature Mt. -

Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan

Durant, S. M., Foley, C., Foley, L., Kazaeli, C., Keyyu, J., Konzo, E., Lobora, A., Magoma, N., Mduma, S., Meing'ataki, G. E. O., Midala, B. D. V. M., Minushi, L., Mpunga, N., Mpuya, P. M., Rwiza, M., and Tibyenda, R. The Tanzania Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan. Durant, S. M., De Luca, D., Davenport, T. R. B., Mduma, S., Konzo, S., and Lobora, A. Report: 162-269. 2009. Arusha, Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute. Keywords: 1TZ/abundance/action plan/caracal/Caracal caracal/conservation/conservation action plan/distribution/ecology/Felis silvestris/Leptailurus serval/serval/wildcat Abstract: This report covers the proceedings of the First Tanzania Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan Workshop held at TAWIRI on 19th-21st April 2006. The workshop brought together key stakeholders to assess existing information and establish a consensus on priorities for research and conservation for 28 species of small to medium carnivore in Tanzania (excluding cheetah, wild dogs, aardwolf, spotted hyaena, striped hyaena, leopard and lion, all of which were covered in other workshops). Recent records were used to confirm the presence of 27 of these species in Tanzania. These were three species of cats or felids: serval (Leptailurus serval); caracal (Caracal caracal) and wild cat (Felis silvestris). Five mustelids: Cape clawless otter (Aonyx capensis); spotted-necked otter (Hydrictis maculicollis); honey badger (Mellivora capensis); striped weasel (Poecilogale albinucha); and zorilla (Ictonyx striatus). Four canids: bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis); black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas); golden jackal (Canis aureus); side-striped jackal (Canis adustus). Four viverrids: common genet (Genetta genetta); large-spotted genet (Genetta maculata); servaline genet (Genetta servalina); and African civet (Viverra civettina). -

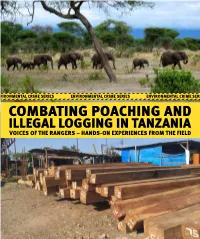

Combating Poaching and Illegal Logging in Tanzania Voices of the Rangers – Hands-On Experiences from the Field

ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD 1 Editorial Team Frode Smeby, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Rune Henriksen, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Christian Nellemann, GRID-Arendal (Current address: Rhipto Rapid Response Unit, Norwegian Center for Global Analyses) Contributors Benjamin Kijika, Commander, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Rosemary Kweka, Pasiansi Wildlife Institute Lupyana Mahenge, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Valentin Yemelin, GRID-Arendal Luana Karvel, GRID-Arendal Anonymous law enforcement officers from across Tanzania. The rangers have been anonymized in order to protect them from the risk of retributions. The authors gratefully acknowledge the sharing of information and experiences by these rangers, who risk their lives every day in the name of conservation. Cartography Riccardo Pravettoni All photos © Frode Smeby and Rune Henriksen Norad is gratefully acknowledged for providing the necessary ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES funding for the project and the production of this publication. 2 COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 WILDLIFE CRIME 6 ILLEGAL LOGGING 9 CHARCOAL 10 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 12 WILDLIFE CRIME 15 EXPERIENCES 16 CHALLENGES 17 SITUATION OF THE LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 21 FIELD EVALUATION OF LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 23 UGALLA GAME RESERVE 29 ILLEGAL LOGGING 35 CORRUPTION AND -

Simiyu Climate Resilience Project

FP041: Simiyu Climate Resilience Project Tanzania | Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) | Decision B.16/23 14 April 2017 Project Title: Simiyu Climate Resilience Project Country/Region: Tanzania Accredited Entity: KfW Date of Submission: _____________________________ Assumed exchange rates: 1 EUR = 2,484 TZS 1 EUR = 1.135 USD Contents Section A PROJECT SUMMARY Section B FINANCING / COST INFORMATION Section C DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION Section D RATIONALE FOR GCF INVOLVEMENT Section E EXPECTED PERFORMANCE AGAINST INVESTMENT CRITERIA Section F APPRAISAL SUMMARY Section G RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT Section H RESULTS MONITORING AND REPORTING Section I ANNEXES Note to accredited entities on the use of the funding proposal template Sections A, B, D, E and H of the funding proposal require detailed inputs from the accredited entity. For all other sections, including the Appraisal Summary in section F, accredited entities have discretion in how they wish to present the information. Accredited entities can either directly incorporate information into this proposal, or provide summary information in the proposal with cross-reference to other project documents such as project appraisal document. The total number of pages for the funding proposal (excluding annexes) is expected not to exceed 50. Please submit the completed form to: [email protected] Please use the following name convention for the file name: “[FP]-[Agency Short Name]-[Date]-[Serial Number]” PROJECT SUMMARY GREEN CLIMATE FUND FUNDING PROPOSAL | PAGE 1 OF 82 A A.1. Brief Project Information A.1.1. Project title Simiyu Climate Resilience Project A.1.2. Project or programme Project A.1.3. Country (ies) / region Tanzania A.1.4. -

Profile on Environmental and Social Considerations in Tanzania

Profile on Environmental and Social Considerations in Tanzania September 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) CRE CR(5) 11-011 Table of Content Chapter 1 General Condition of United Republic of Tanzania ........................ 1-1 1.1 General Condition ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Location and Topography ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.2 Weather ........................................................................................ 1-3 1.1.3 Water Resource ............................................................................ 1-3 1.1.4 Political/Legal System and Governmental Organization ............... 1-4 1.2 Policy and Regulation for Environmental and Social Considerations .. 1-4 1.3 Governmental Organization ................................................................ 1-6 1.4 Outline of Ratification/Adaptation of International Convention ............ 1-7 1.5 NGOs acting in the Environmental and Social Considerations field .... 1-9 1.6 Trend of Aid Agency .......................................................................... 1-14 1.7 Local Knowledgeable Persons (Consultants).................................... 1-15 Chapter 2 Natural Environment .................................................................. 2-1 2.1 General Condition ............................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Wildlife Species .................................................................................. -

Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (Tawiri)

TANZANIA WILDLIFE RESEARCH INSTITUTE (TAWIRI) PROCEEDINGS OF THE ELEVENTH TAWIRI SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE, 6TH – 8TH DECEMBER 2017, ARUSHA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CENTER, TANZANIA 1 EDITORS Dr. Robert Fyumagwa Dr. Janemary Ntalwila Dr. Angela Mwakatobe Dr. Victor Kakengi Dr. Alex Lobora Dr. Richard Lymuya Dr. Asanterabi Lowassa Dr. Emmanuel Mmasy Dr. Emmanuel Masenga Dr. Ernest Mjingo Dr. Dennis Ikanda Mr. Pius Kavana Published by: Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute P.O.Box 661 Arusha, Tanzania Email: [email protected] Website: www.tawiri.or.tz Copyright – TAWIRI 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute. 2 CONFERENCE THEME "People, Livestock and Climate change: Challenges for Sustainable Biodiversity Conservation” 3 MESSAGE FROM THE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE The Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) scientific conferences are biennial events. This year's gathering marks the 11th scientific conference under the Theme: "People, Livestock and Climate change: Challenges for sustainable biodiversity conservation”. The theme primarily aims at contributing to global efforts towards sustainable wildlife conservation. The platform brings together a wide range of scientists, policy markers, conservationists, NGOs representatives and Civil Society representatives from various parts of the world to present their research findings so that management of wildlife resources and natural resources can be based on sound scientific information -

Natural, Cultural and Tourism Investment Opportunities 2017

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND TOURISM NATURAL, CULTURAL AND TOURISM INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 2017 i ABBREVIATIONS ATIA - African Trade Insurance Agency BOT - Build, Operate and Transfers CEO - Chief Executive Officer DALP - Development Action License Procedures DBOFOT - Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer FDI - Foreign Direct Investment GDP - Gross Domestic Product GMP - General Management Plan ICSID - International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes MIGA - Multilateral Investment Guarantee MNRT - Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism Agency MP - Member of Parliament NCA - Ngorongoro Conservation Area NCAA - Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority PPP - Public Private Partnerships TANAPA - Tanzania National Parks TAWA Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority TFS - Tanzania Forest Services TIC - Tanzania Investment Centre TNBC - Tanzania National Business Council VAT - Value Added Tax ii TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND TOURISM ............................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................... 1 TANZANIA IN BRIEF ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 An overview .......................................................................................................................................1 1.2Geographical location and size ........................................................................................................1