Black Dirt Muddy River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

Gulf Islands Real Estate INSIDE on Stage A&E Coverage PAGES 13-17 GGULFULF IISLANDSSLANDS

Gulf Islands Real Estate INSIDE On Stage A&E coverage PAGES 13-17 GGULFULF IISLANDSSLANDS Wednesday, August 31, 2011 — YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1960 51ST YEAR ISSUE 35 $ 25 1(incl. HST) EMERGENCY Car crash sparks brush fi r e Incident points out Garner Road danger BY ELIZABETH NOLAN DRIFTWOOD STAFF Salt Spring Fire-Rescue crews were kept busy over the weekend with nine calls for assistance, including a car crash that turned into a brush fire and sent two people to hospital on Sunday night. At 9:30 p.m. the fi re station received its fourth call of the day, which sent firefighters out to the scene of a motor vehicle incident on Garner Road. According to Salt Spring PHOTO BY DERRICK LUNDY Fire Chief Tom Bremner, a DESTRUCTION: Garner Road resident Mary Burns is seen through the rear window of a burnt-out Ford Explorer that rolled onto her property and Ford Explorer had driven off ignited, along with one of Burns’ vehicles, a cedar tree and surrounding woods on Sunday night. a bank and rolled down onto another car below. The crash HST ignited a fi re involving both vehicles and then extended to the surrounding terrain. Mary Burns, who is a dis- abled resident of 161 Gar- Referendum decision ditches HST ner Rd. and the owner of the parked car, said she was not immediately aware of the sit- Local riding posts fi fth-highest turnout in B.C. uation’s severity. “I heard a bump at that BY SEAN MCINTYRE riding had the fi fth-highest participation rate in She said the referendum result is the demo- moment and I thought it DRIFTWOOD STAFF the province. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

Blaze Damages Ceramic Building

• ev1e Voi.106No.59 University of Delaware, Newqrk. DE Financial aid expecte to be awarded in July By BARBARA ROWLAND To deal with the budgetary The Office of Financial Aid impasse, the university's is anticipating a "bottleneck" financial aid office will send in processing Guaranteed out estimated and unofficial Student Loans (GSLs) as soon award notices on the basis as the federal budget is pass- that the prog19ms will re- ed by-Congr.ess. main the same'-- Because Lhe==amount-oL __- M_ac!)_o_!!ald does 11:0t expect federal funding for both Pell to receive an indication on the Grants and the GSL program amount of. f~ding for Pell has not yet been determined Grants untll this July. the university has not bee~ In an effort to alleviate the - able to award financial aid pressure students may feel packages, according to Direc- -about tuition payments, Mac tor of Financial Aid Douglas Donald said the university MacDonald. will allow students to pay their tuition a quarter at a MacDonald emphasized the time, instead of a half and problem of funding student half installment plan. assistance is not as serious as The university has the problem with delivering also established a $50,000 aid in time for the fall scholarship progr.ani to semester. award students on the basis of MacDonald believes it is both merit and need. unlikely Congress will imple Some of tne changes the ment any changes in the two financial aid office has pro , . _ . Review Photo by Leigh Clifton programs in 1982-83 because jected for next year include: FIREMEN' RESPOND TO A BLAZE at the university's cer'amic building Wednesday night which of the late date. -

Amusement Park Physics Amusement Park PHYSICS

Amusement Park Physics Amusement Park PHYSICS PHYSICS and SCIENCE DAY 2017 Physics 11/12 Amusement Park Physics These educational materials were created by Science Plus. Illustrations, typesetting and layout by Robert Browne Graphics. For more information on Amusement Park Science contact Jim Wiese at [email protected] Vancouver, B.C., Canada April 2017 Materials in this package are under copyright with James Wiese and Science Plus. Permission is hereby given to duplicate this material for your use and for the use of your students, providing that credit to the author is given. Amusement Park Physics Amusement Park Physics and the new Secondary School Curriculum In the past 18 months, the educational system has seen a shift in the science curriculum and changes to how that curriculum is delivered. The current curriculum is more inquiry based with a focus on questioning, predicting, communication, planning and conducting investigations. In addition, students are asked to analyse not only the data they collect, but also the process that was used to collect the data. The curriculum for Science 8 has changed. Although forces are not directly in the current Grade 8 curriculum, inquiry and investigation are at the forefront. Amusement Park Physics can now be applied to any number of classes as they all include an inquiry / investigative component. Teachers are able to adapt or enhance the curriculum packages currently supplied by Amusement Park Physics as they see fit. This gives you, as an educator, tremendous flexibility in terms of how you and your class spend your time at Playland. You could focus on one ride and do an in-depth study or perhaps investigate similar rides and compare them. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

The Ithacan, 1979-11-01

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1979-80 The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 11-1-1979 The thI acan, 1979-11-01 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1979-80 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1979-11-01" (1979). The Ithacan, 1979-80. 10. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1979-80/10 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1979-80 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. f,! ,'I'' A. Weekly Newspaper, Published Independently by the Students of Ithaca College Vol: 49/No. 10 November I. 1979 McCord to Leave Post at IC by Andrea Berm.an cited" about the opportunity, University. said that as of yet, no plans should have been. Charles McCord will be said McCord. But the McCord speculated that the have been set in regards to "In the five years he led our leaving his position as Ithaca "prospect of leaving Ithaca," search for his successor will be filling his position for next development efforts, we have College's V .P. of - College he continued, "where you've starting shortly; hopefully, a semester. raised over $7 million. Our Relations and Resource been for 20 years ... that's a. definite replacement will be in Regarding any projects alumni program has taken on Development to assume the tough one." stated by July. That in presently under his super new vigor, annual giving to the post of Director of University McCord has been with dividual, like McCord, will be vision, McCord said, "there College has more than Relations at the University of Ithaca . -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

The Daily Egyptian, October 06, 1982

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC October 1982 Daily Egyptian 1982 10-6-1982 The aiD ly Egyptian, October 06, 1982 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_October1982 Volume 68, Issue 33 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, October 06, 1982." (Oct 1982). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1982 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in October 1982 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Daily 'Egyptian Wednesday. October II, 19112·VoI. III, No. 33 &aft P .... by Greg Drndma ."'_er Sea. Adlai SleveasOil (left) aIId G~ Jamea TIIomplOll e.c.... ge p9iats III the gubel' DatGr1al debaw at McLeod Tbeater Taesday lliglll. Candidates trade harsh words Voters, was held in. McLeod ~la#i;'~ TMater. It was the third of a series of rour and was the 0IIIy WGN· Trs debate audio cut off ,,'. Both candidates for lllinois one in which the candidates directly asked each other The debate that was to go WGN was using leeds from AI Pizzato, WSIU station governor said they believe statewide education is essential to q\'eStiOIlS. didn't. WSlU, 0uumeI 8, to provide DIP..:Jag.'lI' • alleviate unemployment Stevenson, who proposed to WGN-TV in Chicago lost live coverage over its cable WSW and GTE bad nothing problems and to ensure a stable upgrade teacher training, said Jive audio coverage of the system. However, at about to do with it, be said. The future ior t.'!#! state. -

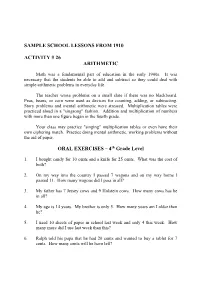

Sample School Lessons from 1910 Activity # 26 Arithmetic

SAMPLE SCHOOL LESSONS FROM 1910 ACTIVITY # 26 ARITHMETIC Math was a fundamental part of education in the early 1900s. It was necessary that the students be able to add and subtract so they could deal with simple arithmetic problems in everyday life. The teacher wrote problems on a small slate if there was no blackboard. Peas, beans, or corn were used as devices for counting, adding, or subtracting. Story problems and mental arithmetic were stressed. Multiplication tables were practiced aloud in a "singsong" fashion. Addition and multiplication of numbers with more than one figure began in the fourth grade. Your class may practice "singing" multiplication tables or even have their own ciphering match. Practice doing mental arithmetic, working problems without the aid of paper. ORAL EXERCISES – 4th Grade Level 1. I bought candy for 10 cents and a knife for 25 cents. What was the cost of both? 2. On my way into the country I passed 7 wagons and on my way home I passed 11. How many wagons did I pass in all? 3. My father has 7 Jersey cows and 9 Holstein cows. How many cows has he in all? 4. My age is 14 years. My brother is only 5. How many years am I older then he? 5. I used 10 sheets of paper in school last week and only 4 this week. How many more did I use last week than this? 6. Ralph told his papa that he had 20 cents and wanted to buy a tablet for 7 cents. How many cents will he have left? 7. -

Coaster Brook Trout: the History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead

Trout Unlimited MINNESOTAThe Official Publication of Minnesota Trout Unlimited - February 2019 March 15th-17th, 2019 l Tickets on Sale Now! without written permission of Minnesota Trout Unlimited. Trout Minnesota of permission written without Copyright 2019 Minnesota Trout Unlimited - No portion of this publication may be reproduced reproduced be may publication this of portion No - Unlimited Trout Minnesota 2019 Copyright Shore Fishing Lake Superior Coaster Brook Trout: The History & Future Artist Profile: Ted Hansen Swinging for Steelhead MNTU Year in Review ROCHESTER, MN ROCHESTER, PERMIT NO. 281 NO. PERMIT Chanhassen, MN 55317-0845 MN Chanhassen, PAID P.O. Box 845 Box P.O. Tying the CDC & Elk U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Minnesota Trout Unlimited Trout Minnesota Non-Profit Org. Non-Profit Trout Unlimited Minnesota Council Update MINNESOTA The Voice of MNTU Meet You at the Expo! By Steve Carlton, Minnesota Council Chair On The Cover appy 2019! May the new year program. The program had a very im- bring more fish and more fishing pressive first half of the school year. Fish A coaster brook trout from Lake Su- Hopportunities…in more fishy tanks in schools around the state are now perior is ready to be released. Learn places! Since our last newsletter, I have filled with young trout growing toward about coaster brook trout, their chal- not had the time to get out, so all I can do release in the spring. Our education lenges, and current work on their be- is look forward to my next opportunity. program can always use your help and half on page 4.