SCSL Press Clippings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inspector General of Government and the Question of Political Corruption in Uganda

Frustrated Or Frustrating S AND P T EA H C IG E R C E N N A T M E U R H H URIPEC FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel Ronald Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER NO. 20 November, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel R. Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER No. 20 NOVEMBER, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA aniel R. Ruhweza Copyright© Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2008 ISBN 9970-511-24-8 HURIPEC Working Paper No. 20 NOVEMBER 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................................................................... i LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS......................………..………............ ii LIST OF LEGISLATION & INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS….......… iii LIST OF CASES …………………………………………………….. .......… iv SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS……...... v I: INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………........ 1 1.1 Working Definitions….………………............................................................... 5 1.1.1 The Phenomenon of Corruption ……………………………………....... 5 1.1.2 Corruption in Uganda……………………………………………….... 6 II: RATIONALE FOR THE CREATION OF THE INSPECTORATE … .... 9 2.1 Historical Context …………………………………………………............ 9 2.2 Original Mandate of the Inspectorate.………………………….…….......... 9 2.3 -

Uganda Chapter Annual Programmes Narrative Report for the Period January

FORUM FOR AFRICAN WOMEN EDUCATIONALISTS (FAWE) UGANDA CHAPTER ANNUAL PROGRAMMES NARRATIVE REPORT FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY – DECEMBER 2016 Plot 328, Bukoto Kampala P.O. Box 24117, Kampala. Tel. 0392....... E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.faweuganda.org 1 1.0 Introduction This annual programme narrative report for the year ending 2016 has been prepared as a reference document for assessing progress of activities implemented by FAWEU during the period under review (i.e. Jan – Dec 2016). The report provides feedback on the progress made in the achievements of set goals, objectives and targets and the challenges met in implementation of activities during the period January – December 2016. 1.2 Overview of the FAWEU Programme The FAWEU programme comprises of a number of projects where majority of them run for a period ranging from one year to three years. The projects address different aspects that are very critical in the empowerment of women and girls to enable them fully participate in the development at all levels. The aspects include; the scholarship component (i.e. school fees/Tuition fees and functional fees, scholastic materials and basic requirements, meals and accommodation and transport), the Advocacy component for awareness creation and fostering positive practices and strategies among different stakeholders for learning and development. Such aspects include; Adolescent Sexual reproductive health (awareness raising through provision of age appropriate information and advocacy), Violence Against, mentoring, counselling and guidance among others. 1. SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM In a bid to enable vulnerable children from disadvantaged backgrounds, FAWEU provides educational support in collaboration with different funders. These include the following; 1.1 KARAMOJA SECONDARY SCHOOL SCHOLARSHIP FAWEU and Irish Aid have been in partnership since 2005 implementing a secondary education programme for vulnerable girls 65% and boys 35%. -

International Court of Justice

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE Peace Palace, Carnegieplein 2, 2517 KJ The Hague, Netherlands Tel.: +31 (0)70 302 2323 Fax: +31 (0)70 364 9928 Website: www.icj-cij.org Press Release Unofficial No. 2011/39 15 December 2011 United Nations General Assembly and Security Council elect Ms Julia Sebutinde as a Member of the Court THE HAGUE, 15 December 2011. The General Assembly and the Security Council of the United Nations elected on Tuesday 13 December Ms Julia Sebutinde as a Member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a term of office of nine years, beginning on 6 February 2012. The biography of Ms Sebutinde is annexed to this press release. It is recalled that on 10 November 2011, Judges Hisashi Owada (Japan), Peter Tomka (Slovakia) and Xue Hanqin (China) were re-elected as Members of the Court. On the same day, Mr. Giorgio Gaja (Italy) was elected as a new Member of the Court. The election of a fifth judge could not be concluded, since no candidate obtained an absolute majority in both the General Assembly and the Security Council. In February 2012, the Court as newly constituted will proceed to elect from among its Members a President and a Vice-President, who will hold office for three years. * For more information on the composition of the Court, the way in which candidacies are submitted and the election procedure, please refer to Press Release 2011/34, which can be found on the Court’s website (www.icj-cij.org) under the heading “Press Room”. Photographs of the election taken at the General Assembly and in the Security Council are available on the United Nations website at the following address: www.unmultimedia.org/photo. -

Kyrgyz Republic

TI 04 chap08 6/1/04 16:14 Page 206 Kyrgyz Republic Corruption Perceptions Index 2003 score: 2.1 (118th out of 133 countries) Bribe Payers Index 2002 score: not surveyed Conventions: UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (signed December 2000; not yet ratified) Legal and institutional changes • The ombudsman law, signed into law in July 2002, provides the legal basis for the ombudsman to ensure official compliance with constitutional rights. It specifies procedures for appointment to – and removal from – the post, as well as its respon- sibilities and investigative procedures (see below). • A commission on legalising the illegal economy, appointed by Prime Minister Nikolai Tanaev in August 2002, was tasked with drafting a programme of work under the chairmanship of Deputy Premier Djoomart Otorbaev and Finance Minister Bolot Abdildaev. The plan envisions four principal projects: economic analysis of the shadow economy; identification of fiscal policy measures; labour force policy; and accounting and registration policy. The goal of all four measures is to bring illegal businesses in all economic sectors into legal conformity. The National Statistics Committee has reported that the shadow economy accounts for at least 13 per cent and as much as 40 per cent of GDP. • A nationwide constitutional referendum approved in February 2003 introduced reforms that included the extension of immunity from prosecution for the first president (see below). • President Askar Akaev signed a decree in February 2003 raising judicial salaries by 50 per cent. He called the decision a move to reduce corruption in the court system. • An anti-corruption law was adopted in March 2003 to highlight and prevent corruption, call offenders to account and create a legal and organisational framework for anti-corruption operations. -

Motivating Challenging Inspiring

A Women’sArise Development Magazine Published by ACFODE Issue 53 November 2012 Motivating Inspiring Challenging 1 2 Vision A just society where there is gender equality of opportunities in all spheres Mission To Promote Women’s Empowerment, Gender Equality and Equity through Advocacy, Network- ing and Capacity Building of both Women and Men Editorial Board Appreciation Helen Twongyeirwe This publication was made pos- Gertrude Ssekabira sible through the kind support of Regina Bafaki Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS). Sandra Nassali ACFODE greatly appreciates this generous contribution. Contents Editorial ........................................................................................................................................................................2 Letters to the Editor ...................................................................................................................................................3 Reaping All the Benefits of a Mentoring Relationship ........................................................................................4 Mentoring the Path to a Better Education and Career ........................................................................................6 Mentoring at the Workplace .....................................................................................................................................9 Parenting in today’s Modern Family ..................................................................................................................... 11 Modest Appearance, -

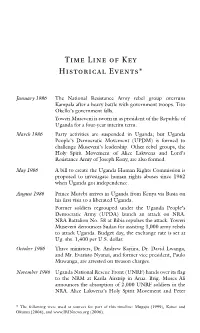

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

70+6'& %%24 0#6+105 +PVGTPCVKQPCNEQXGPCPV Distr. QPEKXKNCP GENERAL RQNKVKECNTKIJVU CCPR/C/UGA/2003/1 25 February 2003 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 40 OF THE COVENANT Initial Report UGANDA* [14 February 2003] * This report is issued unedited, in compliance with the wish expressed by the Human Rights Committee at its sixty-sixth session in July 1999. GE.03-40506 (E) 180903 CCPR/C/UGA/2003/1 page 2 CONTENTS Page PHYSICAL FEATURES ............................................................................................... 6 DEMOGRAPHIC INDICATORS ................................................................................. 6 UGANDA’S INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES ............................................................ 7 BUDGET ....................................................................................................................... 8 APPEALS ...................................................................................................................... 10 GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS THAT PROMOTE AND PROTECT ALL PEOPLE’S CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS ........................................................... 14 The Uganda Human Rights Commission .......................................................... 14 ARTICLE 1: THE RIGHT TO SELF-DETERMINATION ........................................ 14 ARTICLE 2: NON-DISCRIMINATION ..................................................................... 16 ARTICLE 3: EQUAL RIGHTS OF MEN AND WOMEN ........................................ -

Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT PRIVATE ADMISSIONS, 2016/2017 ACADEMIC YEAR PRIVATE THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON PRIVATE SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN DAIRY INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS COURSE CODE ADI INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0540/513 Ssekanjako Emmanuel 2014 U 16 SACRED HEART SEM. MUBENDE 31.6 2 U0083/668 ATUKUNDA Edellah 2015 F U 06 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 30.4 3 U1379/748 NAKAGOLO Shakira Namwebya 2015 F U 35 LUGAZI MIXED SEC. SCH. 27.5 4 U1974/510 OFOYRWOT William 2014 F U 62 ST. PETER'S HS HOIMA 27.4 5 U1365/573 NAMUYINDA Dorcus 2012 F U 45 NILE HIGH SCHOOL 27.3 6 U0857/637 OKELLO Thomas 2012 M U 08 KAJJANSI PROGRESSIVE S.S 26.9 7 U0956/783 KANYESIGYE Anniter 2015 F U 72 NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 26.4 8 U0053/637 KIBIRIGE Ronald 2015 M U 16 MENGO SECONDARY SCHOOL 25.9 9 U0110/574 OCEN Emmanuel 2015 M U 53 BUKOYO SECONDARY SCHOOL 25.6 10 U2222/570 yeko emmanuel 2015 U 20 BUGISU HIGH SCHOOL 25.1 11 U0097/580 opio isaac 2015 U 27 ST.KALEMBA SECONDARY SCHOOL 24.8 12 U0856/535 NALUBINGA JOVIA JULIAN 2015 U 16 ST.ELIZABETH SEC.SCH. NKOOWE 24.6 13 U1379/600 ALAYO Gloria Echodu 2014 F U 106 LUGAZI MIXED SEC. SCH. 24.2 14 U0513/542 MATOVU DICKSON KASOZI 2013 M U 42 KANJUKI S S 22.9 15 U0055/720 NVIRI Rajab 2015 M U 85 BISHOP'S SEC. -

Legal Ethics and Professionalism

Legal Ethics and Professionalism This page was generated automatically upon download from the Globethics.net Library. More information on Globethics.net see https://www.globethics.net. Data and content policy of Globethics.net Library repository see https:// repository.globethics.net/pages/policy Item Type Book Authors Dennison, D. Brian; Tibihikirra-Kalyegira, Pamela Publisher Globethics.net Rights Creative Commons Copyright (CC 2.5) Download date 25/09/2021 06:56:33 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/215288 2 ISBN 978-2-88931-010-4 Law African African Law 2 Legal Ethics and Professionalism A Handbook for Uganda Legal Ethics and Professionalism The Editors D. Brian Dennison is the Acting Dean of the Faculty of Law at Editors Uganda Christian University. Before joining Uganda Christian University in 2008, Brian practiced law in the United States for D. Brian Dennison / nine years. Brian holds a Bachelor in English, a Masters in Business Administration and a Juris Doctorate in Law from the University of Georgia. He is presently pursuing a PhD from the University of Pamela Tibihikirra-Kalyegira Cape Town in Private Law. Pamela Tibihikirra-Kalyegira is the Director of Quality Assur- Legal Ethics ance & Accreditation at Uganda’s National Council of Higher Edu- cation. Previously, Pamela served as the Dean of the Faculty of Law at Uganda Christian University from 2009 to 2014. Pamela holds a and Professionalism Bachelor in Law from Makerere University, a Diploma in Legal Prac- tice from Law Development Centre (Uganda), a Master of Laws Tibihikirra-Kalyegira Pamela Dennison/ Brian D. A Handbook for Uganda from the London School of Economics and a Doctor of Juridical Science from the Indiana University School of Law. -

The Ship 2016/2017

It’s been a turbulent year since the last issue of College St Anne’s The Ship: the shock result of the EU referendum and an unexpected election in the UK; the unexpected result of presidential elections in the USA; the divisive impact across Europe of the biggest refugee exodus since World War II; and the growth of religious intolerance – University of Oxford the underlying cause of terrorist attacks from Manchester and London to the further reaches of the Middle East and Africa. You will find all this reflected in the pages of this issue. And a good deal more of a positive and, College Record St Anne’s I hope, entertaining nature: the British passion for our amazing built heritage, our enduring fascination with crime fiction; a stirring reminder of our College history alongside a vision for its future from our new Principal; and a celebration of the opening of our long-awaited new library. All this and more. With the certain knowledge that I am repeating myself, I marvel every year at the range and engagement of our alumnae 2016 – 2017 across the world. We may not have succeeded in getting a comment direct from President Trump’s Oval Office, but the inimitable Alex, as always, has the last word on the changing face of the student world. • Number I cannot thank all our distinguished contributors enough for taking the time to make this latest issue of The Ship an essential read. There is 106 not the space here to list everything, but don’t • miss out on an unusual Careers Column, nor the Society Annual Publication of the St Anne’s inspirational Donor Column. -

Dormant Accounts

dfcu DORMANT ACCOUNTS 119 2004 dfcu . Dormant Accounts 26 oad P 70 Tel: 0414 351 000 0800 222000 www.dfcugroup.com dfcu Bank Limited is regulated by the Central Bank of Uganda 1 A Page 1-9 B Page 9-17 C Page 17 D Page 17-18 E Page 18-19 F Page 19 G Page 19-21 H Page 21-22 I Page 22-26 J Page 26-34 K Page 34-40 L Page 40-43 M Page 43-98 N Page 98-108 INDEX O Page 108-110 P Page 110-115 Dormant Accounts Q Page 115 R Page 115 S Page 115 T Page 115-116 U Page 116 V Page 116 W Page 116-121 X Page 121 Y Page 121 Z Page 121 2 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME ABIM ATIM SUSAN GRACE ABIM OWILLI AKIO MARY EMMACULATE ABIM ATIN CAL 1 PAPERE GROUP ABIM OWILLI JUSTINE 6TH STREET AYO GRACE ABIM ATWARO CHRISTINE VICKY ABIM OWILLI MATHEW.O.A I.T.O OWILLI 6TH STREET KAKEREWE HUSSEIN KRISTIAN SUNDAY ABIM AUMA ANNA 6TH STREET NAIRUBA DOREEN ABIM OWILLI PETER ABIM AWILLI LILLY 6TH STREET NALUMU MAYIMUNA ABIM PAMBA FARMER FIELD SCHOOL ABIM AYEE YESU WOMEN GROUP 6TH STREET NAMUKWAYA SHARIFAH ABIM RYEM CAN YOUTH GROUP ABIM AYEN JACKSON R.B 6TH STREET OKELLO MOSES ABIM TEM ATEMA FARMER FIELD SCHOOL ABIM AYOO KAMILA ABAITA ABABIRI ABERA ROSE MARY ABIM UGANDA MUSLIM SUPREME COUN- ABIM AYUB- YORA MICRO FINANCE ABAITA ABABIRI AKELLO SUZAN CIL,ABIM DISTRICT GROUP ABAITA ABABIRI ALEMO AGNES ABIM UMOJA AGRO PASTORAL FIELD ABIM BAKALI KABWAKA ABAITA ABABIRI APIO DAPHINE SCHOOL ABIM BALIKOWA HENRY ABAITA ABABIRI BAKAMBAGA GODFREY ABIM WARYEM CAN ORETA GROUP ABIM BEDO ABEDA BAKONYI YOUTH ABIM WELU K’ETHUR CO-OPERATIVE -

African Women Judges on International Courts: Symbolic Or Substantive Gains? Josephine Dawuni Howard University, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 47 | Issue 2 Article 3 2018 African Women Judges on International Courts: Symbolic or Substantive Gains? Josephine Dawuni Howard University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dawuni, Josephine (2018) "African Women Judges on International Courts: Symbolic or Substantive Gains?," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 47 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol47/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AFRICAN WOMEN JUDGES ON INTERNATIONAL COURTS: SYMBOLIC OR SUBSTANTIVE GAINS? Josephine J. Dawuni, Ph.D.* I. INTRODUCTION Scholarship on gender and judging has increased tremendously within the last decade.1 Most of these studies have provided rich empirical and theoretical knowledge on how women have entered judiciaries along with some discussion on what contributions they bring to the bench.2 However, a large part of this scholarship tends to focus on advancing arguments on why courts should be more open to women judges.3 Few studies have looked at women’s ∗ Josephine Jarpa Dawuni is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Howard University in Washington, DC. This research was made possible in part by University of Copenhagen iCourts Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre of Excellence for International Courts.