Intelligence Center of Excellence COL Norman S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Hartford Club Guest of Rotarians Here Will Plan

4 ft**? '*"!' «#<, *-r**i,T'' *•»> * > ..,... '" T'^ :'H • . '*£! Sj-L , V-.J" «•*• #4,? ,&S C?,# x •••••••' ;:-. '" *' \¥" "i^S>J? • : • 7,v#sBffi THE ONLY NEWSPAPER PUBLISHED IN THE TOWN OF ENFIELD, CONN. Fifty-Third Year—No. 24. THOMPSONVILjaErCONN., THURSDAY, SEPT. 29, 1932 Subscription $2.00 Per Year—Single Copy 5c. EAST HARTFORD Things to Remember Before Voting ENDORSED FOR Town Tickets As They Will Be DEMOCRATS TO CLUB GUEST OF At the Town Election Next Monday REGIONAL LOAN HOLD RALLY AT ROTARIANS HERE Voted At Election Next Monday The polls in all three of the voting districts will open at 6 A. M. BANK DIRECTOR THE HIGH SCHOOL and close at 4 P. M. DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN First Inter-City Meeting Avoid confusion by checking up in which district or precinct you Assessor are registered before balloting. Walter P. Schwabe Be Michael A. Mitchell Henry J. Bridge Local Candidates And Proves Unusually Suc _ Jn Thompsonville, if you live south of the Asnuntuck Brook, the ing Urged For Direc jrona or Freshwater Brook you are in Precinct 1, and you vote at the Board of Relief Out of Town Speakers cessful— Rev. Charles Town Court Room. torship of New Eng Michael J. Liberty Jeremiah H. Provencher Will Be Heard Tomor Noble of Hartford Ad If you live on the north side of the above named bodies of water Selectmen you are in Precinct 2, and your voting place is the Higgins School land Branch,of Federal Patrick T. Malley Orrin W. Beehler row Night—No Repub dresses Gathering. Auditorium. Francis T. Carey Robert J. -

Brig Gen George M. Reynolds

BRIG GEN GEORGE M. REYNOLDS Brigadier General George M. “Moose” Reynolds is Vice Commander of the 25th Air Force, Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, Texas. He is responsible to the commander for providing multisource intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance products, applications, capabilities and resources; electronic warfare and integrating cyber ISR forces and expertise. The 25th Air Force includes the 70th, 363rd and 480th ISR Wings, the 9th Reconnaissance Wing, 55th Wing, 319th Air Base Wing, the Air Force Technical Applications Center and all Air Force cryptologic operations. These units include more than 29,000 Airmen worldwide providing flexible collection, analysis, weapons monitoring and operational intelligence to joint warfighters and the national intelligence community. Prior to his current assignment, Brig Gen Reynolds was the Air Force Military Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations, New York City, New York. He participated in a competitively selective education program focused on national security policy research and strengthening relationships with civilian academic and policy communities. Previously, Brig Gen Reynolds commanded a flying training squadron, four expeditionary squadrons, operations group, and wing. He has served on the numbered air force, center, air and joint staffs. Brig Gen Reynolds received his commission from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1992. He is a command pilot with more than 2,400 flying hours in the RC-135V/W, OC-135B, WC-135W, EC- 130E/H, C-130E/H, T-38, and T-37. He has flown combat missions in operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. EDUCATION: 1992 Bachelor of Science in Ops Research, United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colo. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6"X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World’s Information since 1938 300 North Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820321 Operational art and the German command system in World War I Meyer, Bradley John, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1088 by Meyer, Bradley John. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 OPERATIONAL ART AND THE GERMAN COMMAND SYSTEM IN WORLD WAR I DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Bradley J. -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS Case No. 12 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -against- WILHELM' VON LEEB, HUGO SPERRLE, GEORG KARL FRIEDRICH-WILHELM VON KUECHLER, JOHANNES BLASKOWITZ, HERMANN HOTH, HANS REINHARDT. HANS VON SALMUTH, KARL HOL LIDT, .OTTO SCHNmWIND,. KARL VON ROQUES, HERMANN REINECKE., WALTERWARLIMONT, OTTO WOEHLER;. and RUDOLF LEHMANN. Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NORNBERG 1947 • PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ TABLE OF CONTENTS - Page INTRODUCTORY 1 COUNT ONE-CRIMES AGAINST PEACE 6 A Austria 'and Czechoslovakia 7 B. Poland, France and The United Kingdom 9 C. Denmark and Norway 10 D. Belgium, The Netherland.; and Luxembourg 11 E. Yugoslavia and Greece 14 F. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 17 G. The United states of America 20 . , COUNT TWO-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST ENEMY BELLIGERENTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR 21 A: The "Commissar" Order , 22 B. The "Commando" Order . 23 C, Prohibited Labor of Prisoners of Wal 24 D. Murder and III Treatment of Prisoners of War 25 . COUNT THREE-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST CIVILIANS 27 A Deportation and Enslavement of Civilians . 29 B. Plunder of Public and Private Property, Wanton Destruc tion, and Devastation not Justified by Military Necessity. 31 C. Murder, III Treatment and Persecution 'of Civilian Popu- lations . 32 COUNT FOUR-COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY 39 APPENDIX A-STATEMENT OF MILITARY POSITIONS HELD BY THE DEFENDANTS AND CO-PARTICIPANTS 40 2 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ INDICTMENT -

HM Forces: Applications on Discharge

HM Forces: applications on discharge This guidance is based on the Immigration Rules Appendix Armed Forces Page 1 of 24 HM Forces: applications on discharge v3.0 Published for home Office staff on 14 May 2015 HM Forces: applications on discharge About this guidance About this guidance This guidance tells you about settlement applications from members of HM Forces who In this section Key facts have been discharged. Changes to this Discharged armed guidance forces members: In this guidance ‘armed forces rules’ means Appendix Armed Forces. Contacts eligibility criteria Information owner Medical discharge ‘HM Forces’ means a member of the Royal Navy, British Army or Royal Air Force who is Ministry of Defence serving as a member of the regular forces. Related Links disciplinary procedures Links to staff intranet Grant or refuse entry ‘Gurkha’ means someone enlisted in the Brigade of Gurkhas as part of the British Army. removed clearance ‘Discharge’ means an HM Forces member who has permanently left HM Forces. All those who have been discharged will hold a certificate of discharge. Those about to be discharged External links will hold a letter from their commanding officer confirming their date and reasons for discharge. Appendix Armed Forces Anyone compelled to leave HM Forces following a court martial has not been discharged but Immigration Act 1971 dismissed. ‘Medical discharge’ is when an HM Forces member is prematurely discharged because their health prevents effective service. They will often receive compensation for this discharge. ‘Reckonable service’ is the service which counts towards pension. This starts from the first day of paid service in HM Forces and does not include certain absences including any period of detention, unauthorised absence or unpaid leave. -

Military Administrative Discharges—The Pendulum Swings

MILITARY ADMINISTRATIVE DIS- CHARGES-THE PENDULUM SWINGS ROBINSON 0. EVERETT* The type of discharge which a man receives upon being separated from the Armed Services can have a profound effect on his civilian life. Not unexpectedly, therefore, much concern has been recently expressed concerning the safeguards and procedures available to the serviceman to contest an unfavorable discharge, both before and after termination of his military service. This article ex- haustively examines the problems surrounding the administrative discharge and the limitations being imposed on its unfair use by the military itself, by the courts, and by Congress. INTRODUCTION N 1962 the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate Judiciary Committee opened legislative hearings on the consti- tutional rights of military personnel by emphasizing concern that |administrative discharges were being increasingly used by the Armed Services to circumvent safeguards for the serviceman which Congress had provided in the Uniform Code of Military Justice.1 Those hearings resulted in a number of legislative recommendations 2 and the introduction by Senator Sam J. Ervin, Jr. of several bills to provide service personnel with new protection in military ad- ministrative actions and to reverse the trend towards their use.3 None of these bills was the subject of hearings during the Eighty- Eighth Congress; but they were all reintroduced in the present * A.B. 1947, LL.B. 1950, Harvard University. Adjunct Professor of Law, Duke University. Consultant and former Counsel, Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Author, MILITARY JUSTICE IN THE ARMED FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES (1956). 1 See Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. -

C:/Users/User/Desktop/2017-08-16 Tannenberg Booklet 6 Seiten BGG

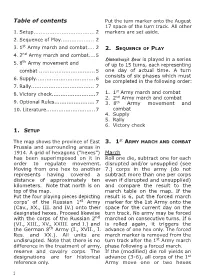

Table of contents Put the turn marker onto the August 17 space of the turn track. All other 1. Setup................................... 2 markers are set aside. 2. Sequence of Play................... 2 st 3. 1 Army march and combat.... 2 2. SEQUENCE OF PLAY 4. 2nd Army march and combat....5 th Hindenburg’s Hour is played in a series 5. 8 Army movement and of up to 15 turns, each representing combat ................................ 5 one day of actual time. A turn consists of six phases which must 6. Supply..................................6 be completed in the following order: 7. Rally.................................... 7 st 8. Victory check.........................7 1. 1 Army march and combat 2. 2nd Army march and combat 9. Optional Rules....................... 7 3. 8th Army movement and 10. Literature............................ 7 combat 4. Supply 5. Rally 6. Victory check 1. SETUP The map shows the province of East 3. 1st ARMY MARCH AND COMBAT Prussia and surrounding areas in 1914. A grid of hexagons (“hexes”) March has been superimposed on it in Roll one die, subtract one for each order to regulate movement. disrupted and/or unsupplied (see Moving from one hex to another 7.) corps in the army (do not represents having covered a subtract more than one per corps distance of approximately ten even if disrupted and unsupplied) kilometers. Note that north is on and compare the result to the top of the map. march table on the map. If the Put the four playing pieces depicting result is 6, put the forced march corps’ of the Russian 1st Army marker for the 1st Army onto the (Cav., XX., III. -

Digital Download (PDF)

Q&A: JCS Vice Roles and Missions Reboot? 48| Pilot Training 44| Cost-Per-E ect Calculus 60 Chairman Gen. John Hyten 14 THE NEW ARCTIC STRATEGY Competition Intensifies in a Critical Region |52 September 2020 $8 Published by the Air Force Association THOSE BORN TO FLY LIVE TO WALK AWAY ACES 5®: Proven and ready Protecting aircrew is our mission. It’s why our ACES 5® ejection seat is the world’s only production seat proven to meet the exacting standards of MIL-HDBK-516C. Innovative technologies and consistent test results make ACES 5 the most advanced protection for your aircrew. Plus, we leverage 40 years of investment to keep your life-cycle costs at their lowest. ACES 5: Fielded and available today. The only ejection seat made in the United States. collinsaerospace.com/aces5 © 2020 Collins Aerospace CA_8338 Aces_5_ProvenReady_AirForceMagazine.indd 1 8/3/20 8:43 AM Client: Collins Aerospace - Missions Systems Ad Title: Aces 5 - Eject - Proven and Ready Filepath: /Volumes/GoogleDrive/Shared drives/Collins Aerospace 2020/_Collins Aerospace Ads/_Mission Systems/ACES 5_Ads/4c Ads/ Eject_Proven and ready/CA_8338 Aces_5_ProvenReady_AirForceMagazine.indd Publication: Air Force Magazine - September Trim: 8.125” x 10.875” • Bleed: 8.375” x 11.125” • Live: 7.375” x 10.125” STAFF Publisher September 2020. Vol. 103, No. 9 Bruce A. Wright Editor in Chief Tobias Naegele Managing Editor Juliette Kelsey Chagnon Editorial Director John A. Tirpak News Editor Amy McCullough Assistant Managing Editor Chequita Wood Senior Designer Dashton Parham Pentagon Editor Brian W. Everstine Master Sgt. Christopher Boitz Sgt. Christopher Master Digital Platforms Editor DEPARTMENTS FEATURES T-38C Talons Jennifer-Leigh begin to break 2 Editorial: Seize 14 Q&A: The Joint Focus Oprihory the High Ground away from an echelon for- Senior Editor By Tobias Naegele Gen. -

Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War Andrew Loren Jones East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2014 Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War Andrew Loren Jones East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Andrew Loren, "Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2387. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2387 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War ___________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ________________________________________ by Andrew L. Jones May 2014 ________________________________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Dr. John M. Rankin Keywords: Nationalism, Delbrück, Schlieffen, German War Planning, Germany, Sedan, Moltke, War Enthusiasm, German Wars of Unification, World War I ABSTRACT Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War by Andrew L. Jones Debating Cannae: Delbrück, Schlieffen, and the Great War provides the reader a view of the historical struggle between Alfred von Schlieffen and Hans Delbrück. They argued fiercely about the foundation of the German Empire and the use of history. -

FPCD-80-13 Military Discharge Policies and Practices Result In

_‘ !\I 33y BY THECOMPTROLLER GENERAL 7%~ Report To The Congress OF THE UNITED STATES Military Discharge Policies And Practices Result In Wide Disparities: Congressional Review Is Needed The military services characterize a member’s service by the type of discharge imposed at separation. Different philosophies and prac- tices among the services for imposing and up- grading discharges have led to wide disparities, which erode the integrity of the system. Therefore, the type of discharge may have little to do with the former service member’s performance on active duty. Many with less than fully honorable discharges may have better service records than others with fully honorable discharges. Yet these judgments are used to differentiate among former service members, usually without further review. This report discusses these problems and makes recommendations to the Secretary of Defense. The Congress should also consider the problems discussed and decide the future of the services’ characterization and separa- tion systems. 111337 COMPTROLLER OENLRAL OC THE UNITED STATES wA8HINoToN. D.C. zou8 B-197168 To the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives f M/O LloflQ I The military departments characterize the service of each member by the type of discharge imposed when the in- dividual is separated. The current system of discharyes was adopted by the Department of Defense in 1947, but each service has developed and implemented its own philosophies and practices. As a result, people with similar service records are getting different types of discharges. The most favorable type of discharge--the honorable-- should be reserved for honest and faithful service but is awarded to many persons discharyed for reasons indicating they were not successful. -

Timeline of Service

Timeline of Service Captain Robert B Hermann 8th Army Air Corp, 306th Bomb Group, 367th Bomb Squadron Navigator Boeing B-17F-30-BO, #42-5130, Sweet Pea, Pilot, Capt. John L Ryan From: 289 North High Street, Chillicothe, Ohio Born: 25 Dec 1918 Died: 22 July 1990 Elgin, IL Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Washing DC, Section 70 Grave #1821 Serial Number: 0-660491 6 Dec 1941, Enlisted as Aviation Cadet Fort Hayes Columbus Ohio 11 Dec 1941, Basic training at Ellington Field Texas 7 Feb 1942, Navigation School, Kelly Field Teas 23 May 1943, Commissioned 2nd Lt 9 June 1942, Assigned to 306th Bomb group at Wendover Air Field Utah 6 Aug 1942, Transferred to Westover Air Field MA 5 Sept 1942 – 8 Sept 1942, Flew overseas to Thurleigh England, 31 Dec 1942, Promoted to 1st Lt 6 Mar 1943, Shot down on mission to Lorient France, MACR- 15568 8 Mar to 17 Mar1943, Sent to Dulag III Frankfort Germany for interrogation 20 Mar to 8 Apr 1943, Sent to Oflag 21B Apr 1943 to Jan 1945, POW Stalag Luft III, Sagan Germany (now Zagan Poland) Jan 1945, Marched to Stalag VII A, Mossburg Germany 29 Apr 1945, Liberated 16 July 1945, Returned to USA 8 Oct 1945, Promoted to Captain 20 Dec 1945, Discharged Danville Ky. Missions List: 9 Oct 1942, Lille France (Pilot Capt. John Ryan) 7 Nov 1942, Brest France 8 Nov 1942, Lille France (Pilot Capt. Lambert) 9 Nov 1942, St. Nazaire France 14 Nov 1942, St. Nazaire France 18 Nov 1942, La Pallice France 22 Nov 1942, Lorient France Timeline of Service 12 Dec 1942, Rouen France 20 Dec 1942, Romilly-sur-Seine -

V^Ciocc1, Primarily O.. J Trrnalation Of) 1 R;Jt.^Rb^I>G-- Viic Cc

hi.. ":Ui('-(t> >it! •/..'/><* ttirhyft-.rti.r. ,V./iV /../.. '.i,iuith-ir»rh ti>i it iktfu a././ <r V^ciocc1, primarily o.. J trrnalation of) 1 r;jT.^rB^i>G-- viic cc '.-virkllch v;ar,by / imade bj auf.h:r uf hhie article. ; .• . ... _ , , . , , . , , , , , t . , '.,;",•;,••'• •; ' . •' •<. ' '.' ' 7 " ! r " '• " ' ' "';/ ...... ,, ./ i ii ,V I it i l! II >t •< . •ili'iii I i ii I, „ „ .. II . •-. >.i) II ;. .. .i >t it H it li it ,f)i u ,i Hi, il-ul CODE; tflWBER , IR—1933 I N D IV ID U A ij *RES EAR OH STUDY A CRITICAL AKALY8I& OP TtiE BATTLE OP TANNENBERO •••i; " . • : , (baaed primarily on a translation of nTANNENEERQ--wie es wirklieh war11 General Max Hoffmann) Submitted by \ THIS SOLUTICM MtiST BS RiSTURf^ED FOR FILE BY 5:00 >!W,, OUTHE DATS SKOSN •PLEABB PLACE Y'jUR NAME ON COVZR PACE HiE WRNI1W. FOR FU.E LBUT DO NOV PLACE VGUK 1 0» SOLUTION IWEif WRESTING A RDVIEff. The Command and General Staff School .'.}••• Leavenworth'' , •Kansa ' s Fort Leftv>nworth, Kansas, May IB; 1933 MEMORANDUM FOR: The Director Second Year Class, The Com mand and Oeneral Staff School, Fort Leavehworth, Kansas. A:Crjitioal Anaiysis :o£ the Battle of Tan enberg (based primarily oh•aftranslation of "Tannenberg wie es wirklioh war" by Max Hoffmann) I, PAPERS ACCOMPANYING: 1. A Bibliography for this study. 2. Maps: (1) Strategic Map--East Prussia, Campaign SO $d^&hj6e;J^^ 'Armiejst &) J'JBi^^le'j^of'^^ia%7'-F^a)^enjaii 4) !'$ei^u<iti ioh^'/bif;;.inu81lB'ian r igfifc 'tlank 5) Attack on Russian left, August 26-28, • ' 101^ ' •' ', i JL v J L * ^ ' ', :; • '• J > (6) Attaok on Russian Center, August 26-28, 1914.