Alternative Visual Discourse and the Documentaries of Hu Jie and Wang Bing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

From" Morning Sun" To" Though I Was Dead": the Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident"

From" Morning Sun" to" Though I Was Dead": The Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident" Wei-li Wu, Taipei College of Maritime Technology, Taiwan The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2016 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This year is the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. On August 5, 1966, Bian Zhongyun, the deputy principal at the girls High School Attached to Beijing Normal University, was beaten to death by the students struggling against her. She was the first teacher killed in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and her death had established the “violence” nature of the Cultural Revolution. After the Cultural Revolution, the reminiscences, papers, and comments related to the “August Fifth Incident” were gradually introduced, but with all blames pointing to the student leader of that school, Song Binbin – the one who had pinned a red band on Mao Zedong's arm. It was not until 2003 when the American director, Carma Hinton filmed the Morning Sun that Song Binbin broke her silence to defend herself. However, voices of attacks came hot on the heels of her defense. In 2006, in Though I Am Gone, a documentary filmed by the Chinese director Hu Jie, the responsibility was once again laid on Song Binbin through the use of images. Due to the differences in perception between the two sides, this paper subjects these two documentaries to textual analysis, supplementing it with relevant literature and other information, to objectively outline the two different images of Song Binbin in the “August Fifth Incident” as perceived by people and their justice. -

2.17 Shanghai City Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development

2.17 Shanghai City Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development (Group) Co., Ltd., affiliated with the Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration Bureau, has 20 prison enterprises1 Legal representative of the prison company: Mao Guoping, Chairman of Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development (Group) Co., Ltd. His official positions in the prison system: Director of Planning and Finance Division of Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration Bureau2 The Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration now administers 11 prisons and one Juvenile Delinquency Reformatory. Among them, the Baimaoling Prison and Juntianhu Prison are located in the Wannan area (i.e. southern part of Anhui Province). There are also the Prison General Hospital, the Judicial Police School and a number of security enterprises that serve the prison-related work. Since 1949, these prisons have accumulatively detained more than 400,000 criminals.3 No. Company Name of the Prison, Legal Person Legal Registered Business Scope Company Address Notes on the Prison Name to which the and representative / Capital Company Belongs Shareholder(s) Title 1 Shanghai Shanghai Municipal Shanghai Mao Guoping 11.846 Industrial investment, Building No. 150, 111 The main responsibilities of the Shanghai Shenyue Prison Municipal million business management, Changyang Road, Municipal Prison Administration Bureau and Chairman of Enterprise Administration Prison yuan financial consulting Shanghai City its staffing are according to the “Notice of the Shanghai Developme Bureau Administration (actually services, commercial General Office of the Chinese Communist nt (Group) Shenyue paid 77.148 activities, domestic Bureau Enterprise Party Central Committee and the General Co., Ltd. million trading Office of the State Council, regarding the Development yuan) (Group) Co., Shanghai Municipal People’s Government Ltd.; Director of Institutional Reform Scheme” (No. -

Master for Quark6

Special feature s e Finding a Place for v i a t c n i the Victims e h p s c The Problem in Writing the History of the Cultural Revolution r e p YOUQIN WANG This paper argues that acknowledging individual victims had been a crucial problem in writing the history of the Cultural Revolution and represents the major division between the official history and the parallel history. The author discusses the victims in the history of the Cultural Revolution from factual, interpretational and methodological aspects. Prologue: A Blocked Web topic “official history and parallel history” of the Cultural Memorial Revolution. In this paper I will argue that acknowledging individual vic - n October of 2000, I launched a website, www.chinese- tims has been a crucial problem in writing the history of the memorial.org , to record the names of the people who Cultural Revolution and represents the major division be - Idied from persecution during the Cultural Revolution. tween the official history that the Chinese government has Through years of research, involving over a thousand inter - allowed to be published and the parallel history that cannot views, I had compiled the stories of hundreds of victims, and pass the censorship on publications in China. As of today, placed them on the website. By clicking on the alphabeti - no published scholarly papers have analyzed the difference cally-listed names, a user could access a victim’s personal in - between the two resulting branches in historical writings on formation, such as age, job, date and location of death, and the Cultural Revolution. -

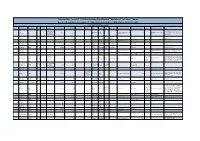

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps Based on Reports Received January - December 2009, Listed in Descending Order by Sentence Length Falun Dafa Information Center Case # Name (Pinyin)2 Name (Chinese) Age Gender Occupation Date of Detention Date of Sentencing Sentence length Charges City Province Court Judge's name Place currently detained Scheduled date of release Lawyer Initial place of detention Notes Employee of No.8 Arrested with his wife at his mother-in-law's Mine of the Coal Pingdingshan Henan Zhengzhou Prison in Xinmi City, Pingdingshan City Detention 1 Liu Gang 刘刚 m 18-May-08 early 2009 18 2027 home; transferred to current prison around Corporation of City Province Henan Province Center March 18, 2009 Pingdingshan City Nong'an Nong'an 2 Wei Cheng 魏成 37 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 18 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2027 Arrested from home; County Court Zhejiang Fuyang Zhejiang Province Women's 3 Jin Meihua 金美华 47 f 19-Nov-08 15 Fuyang City November, 2023 Province City Court Prison Nong'an Nong'an 4 Han Xixiang 韩希祥 42 m Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Nong'an Nong'an 5 Li Fengming 李凤明 45 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Arrested from home; detained until late April Liaoning Liaoning Province Women's Fushun Nangou Detention 6 Qi Huishu 齐会书 f 24-May-08 Apr-09 14 Fushun City 2023 2009, and then sentenced in secret and Province Prison Center transferred to current prison. -

The Beijing University Student Movement in the Hundred Flowers

The Beijing University Student Movement in the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1957 Yidi Wu Senior Honors, History Department, Oberlin College April 29, 2011 Advisor: David E. Kelley Wu‐Beijing University Student Movement in 1957 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: The Hundred Flowers Movement in Historical Perspective..................... 6 Domestic Background.......................................................................................... 6 International Crises and Mao’s Response............................................................ 9 Fragrant Flowers or Poisonous Weeds ............................................................... 13 Chapter 2: May 19th Student Movement at Beijing University ............................... 20 Beijing University before the Movement .......................................................... 20 Repertoires of the Movement.............................................................................. 23 Student Organizations......................................................................................... 36 Different Framings.............................................................................................. 38 Political Opportunities and Constraints ............................................................. 42 A Tragic Ending ................................................................................................. 46 Chapter 3: Reflections on -

|||FREE||| Monkey House Blues: a Shanghai Prison

MONKEY HOUSE BLUES: A SHANGHAI PRISON MEMOIR FREE DOWNLOAD Dominic Stevenson | 240 pages | 01 May 2010 | Mainstream Publishing | 9781845965662 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Download In Pdf Tyrrell rated it really liked it Jul 24, Thirteen Chinese hanjian prisoners being executed inside the prison's walls. Read more. Lists with This Book. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. InMonkey House Blues: A Shanghai Prison Memoir Stevenson left a comfortable life with his girlfriend in Kyoto, Japan, to travel to China. Ranmalee Gamage rated it it was amazing Jul 28, Sarah rated it it was amazing Dec 30, Prisons in China. This is the memoir of a young man who ended up in a Shanghai jail in China for drug smuggling. OneWay Ticket. Going to Court. I am promise you will like the My Private China. Trivia About Monkey House Blue Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. April 09, The KMT used the prison to detain several hundred Japanese war criminals and a number of Chinese who had been part of Wang Jingwei's government. Get A Copy. Shannon Styles rated it really liked it Dec 31, All your favorite books and authors in one place! All your favorite books and …. In a decision was made to no longer imprison Western convicts at Ward Road, instead sending them to the Settlement's Caucasian-only prison: Amoy Road Gaol. The majority of warders were Indian Sikhswho were generally despised by Chinese prisoners. Published May 1st by Mainstream Publishing first published Today Tilanqiao Prison is Monkey House Blues: A Shanghai Prison Memoir of China's largest and most in famous prisons, often held and reported as a model prison by the PRC state. -

Report Into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China

REPORT INTO ALLEGATIONS OF ORGAN HARVESTING OF FALUN GONG PRACTITIONERS IN CHINA by David Matas and David Kilgour 6 July 2006 The report is also available at http://davidkilgour.ca, http://organharvestinvestigation.net or http://investigation.go.saveinter.net Table of Contents A. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................- 1 - B. WORKING METHODS ...................................................................................................................................- 1 - C. THE ALLEGATION.........................................................................................................................................- 2 - D. DIFFICULTIES OF PROOF ...........................................................................................................................- 3 - E. METHODS OF PROOF....................................................................................................................................- 4 - F. ELEMENTS OF PROOF AND DISPROOF...................................................................................................- 5 - 1) PERCEIVED THREAT .......................................................................................................................................... - 5 - 2) A POLICY OF PERSECUTION .............................................................................................................................. - 9 - 3) INCITEMENT TO HATRED ................................................................................................................................- -

Cultural Reviews

CULTURAL REVIEWS Bian Zhongyun: lived. Given its proximity to the central government and State Council, as well as its long-standing reputation for A Revolution’s First Blood excellence, the Attached Girls’ School was inevitably By Wang Youqin attended by many daughters of China’s top leaders. The senseless death of a school teacher set the tone for Mao At that time, entry to all secondary schools required Zedong’s 10-year reign of terror, the Cultural Revolution. passing city-wide examinations for both middle and high school. Prior to the Cultural Revolution, however, Bian Zhongyun was born in 1916 in Wuwei, Anhei examination results were not the sole criteria for entry. Province. Her father worked his way up from a strug - In the autumn of 1965, shortly before the Cultural Rev - gling apprentice in a private bank to the wealthy and olution began, half of the students at the Attached Girls’ socially prominent owner of his own private bank. After School were the daughters or relatives of senior govern - Bian Zhongyun graduated from high school in 1937, her ment officials. This element became an important fac - plans to enter college were interrupted by China’s war tor leading to Bian Zhongyun’s death. with Japan, and she participated in the resistance effort in Changsha. She was finally able to attend college in The sequence of events resulting in Bian Zhongyun’s 1941, and became a member of the Communist Party of death began on June 1, 1966. On that evening, the China (CPC) in the same year. She graduated in 1945 China Central People’s Broadcasting Network broad - and then joined her husband, Wang Jingyao (who had casted the contents of what Mao Zedong referred to as studied with her in college), in the Party-controlled area “China’s first Marxist-Leninist big-character poster,” of China. -

The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement for the Public Record

The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement For the Public Record Edited by Chris Berry, Lu Xinyu, and Lisa Rofel Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2010 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8028-51-1 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8028-52-8 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Printed and bound by CTPS Digiprints Limited in Hong Kong, China Table of Contents List of Illustrations vii List of Contributors xi Part I: Historical Overview 1 1. Introduction 3 Chris Berry and Lisa Rofel 2. Rethinking China’s New Documentary Movement: 15 Engagement with the Social Lu Xinyu, translated by Tan Jia and Lisa Rofel, edited by Lisa Rofel and Chris Berry 3. DV: Individual Filmmaking 49 Wu Wenguang, translated by Cathryn Clayton Part II: Documenting Marginalization, or Identities New and Old 55 4. West of the Tracks: History and Class-Consciousness 57 Lu Xinyu, translated by J. X. Zhang 5. Coming out of The Box, Marching as Dykes 77 Chao Shi-Yan Part III: Publics, Counter-Publics, and Alternative Publics 97 6. Blowup Beijing: The City as a Twilight Zone 99 Paola Voci vi Table of Contents 7. -

Popular Memories of the Mao Era

Popular Memories of the Mao Era From Critical Debate to Reassessing History Edited by Sebastian Veg Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.hku.hk © 2019 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-76-2 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction: Trauma, Nostalgia, Public Debate 1 Sebastian Veg Part I. Unofficial Memories in the Public Sphere: Journals, Internet, Museums 2. Writing about the Past, an Act of Resistance: An Overview of Independent Journals and Publications about the Mao Era 21 Jean-Philippe Béja 3. Annals of the Yellow Emperor: Reconstructing Public Memory of the Mao Era 43 Wu Si 4. Contested Past: Social Media and the Production of Historical Knowledge of the Mao Era 61 Jun Liu 5. Can Private Museums Offer Space for Alternative History? The Red Era Series at the Jianchuan Museum Cluster 80 Kirk A. Denton Part II. Critical Memory and Cultural Practices: Reconfiguring Elite and Popular Discourse 6. Literary and Documentary Accounts of the Great Famine: Challenging the Political System and the Social Hierarchies of Memory 115 Sebastian Veg 7. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2012

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2012 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov 2012 ANNUAL REPORT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2012 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–190 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, SHERROD BROWN, Ohio, Cochairman Chairman MAX BAUCUS, Montana FRANK WOLF, Virginia CARL LEVIN, Michigan DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California EDWARD R. ROYCE, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JAMES RISCH, Idaho MICHAEL M. HONDA, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS SETH D. HARRIS, Department of Labor MARIA OTERO, Department of State FRANCISCO J. SANCHEZ, Department of Commerce KURT M. CAMPBELL, Department of State NISHA DESAI BISWAL, U.S. Agency for International Development PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director LAWRENCE T. LIU, Deputy Staff