Near Life, Queer Death Overkill and Ontological Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexualities and Genders in Education

SEXUALITIES AND GENDERS IN EDUCATION Towards Queer Thriving Adam J. Greteman QUEER Series Editors STUDIES & William F. Pinar EDUCATION Nelson M. Rodriguez, & Reta Ugena Whitlock Queer Studies and Education Series editors William F. Pinar Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy University of British Columbia Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Nelson M. Rodriguez Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexual Studies The College of New Jersey Ewing, New Jersey, USA Reta Ugena Whitlock Department of Educational Leadership Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia, USA LGBTQ social, cultural, and political issues have become a defining fea- ture of twenty-first century life, transforming on a global scale any number of institutions, including the institution of education. Situated within the context of these major transformations, this series is home to the most compelling, innovative, and timely scholarship emerging at the intersec- tion of queer studies and education. Across a broad range of educational topics and locations, books in this series incorporate lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex categories, as well as scholarship in queer theory arising out of the postmodern turn in sexuality studies. The series is wide- ranging in terms of disciplinary/theoretical perspectives and methodolog- ical approaches, and will include and illuminate much needed intersectional scholarship. Always bold in outlook, the series also welcomes projects that challenge any number of normalizing tendencies within academic scholar- ship from works that move beyond established frameworks of knowledge production within LGBTQ educational research to works that expand the range of what is institutionally defined within the field of education as relevant queer studies scholarship. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14522 Adam J. -

Reviving the Queer Political Imagination

Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity Ryan Conrad A Thesis in the Humanities Interdisciplinary Program Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2017 © Ryan Conrad, 2017 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ryan Conrad Entitled: Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Rebecca Duclos Susan Knabe External Examiner Monika Gagnon External to Program Anne Whitelaw Examiner Deborah Gould Examiner Thomas Waugh Thesis Supervisor Approved by: Graduate Program Director 10 April 2017 Dean of Faculty Abstract Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity Ryan Conrad, PhD Concordia University, 2017 Through investigating three cultural archives spanning the last three decades, this dissertation elucidates the causes and dynamics of the sharp conservative turn in gay and lesbian politics in the United States beginning in the 1990s, as well as the significance of this conservative turn for present-day queer political projects. While many argue -

Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

WHEN STATES ‘COME OUT’: THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY AND THE DIFFUSION OF SEXUAL MINORITY RIGHTS IN EUROPE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Phillip Mansour Ayoub August 2013 © 2013 Phillip Mansour Ayoub WHEN STATES ‘COME OUT’: THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY AND THE DIFFUSION OF SEXUAL MINORITY RIGHTS IN EUROPE Phillip Mansour Ayoub, Ph. D. Cornell University 2013 This dissertation explains how the politics of visibility affect relations among states and the political power of marginalized people within them. I show that the key to understanding processes of social change lies in a closer examination of the ways in which—and the degree to which—marginalized groups make governments and societies see and interact with their ideas. Specifically, I explore the politics of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) visibility. For a group that many observers have referred to as “an invisible minority,” the newfound presence and influence of LGBT people in many different nation states offers fresh opportunities for the study of socio-political change and the diffusion of norms. Despite similar international pressures, why are the trajectories of socio-legal recognition for marginalized groups so different across states? This question is not answered by conventional explanations of diffusion and social change focusing on differences in international pressures, the fit between domestic and international norms, modernization, or low implementation costs. Instead, specific transnational and international channels and domestic interest groups can make visible political issues that were hidden, and it is that visibility that creates the political resonance of international norms in domestic politics, and can lead to their gradual internalization. -

LG MS 35 Ryan Conrad Collection Finding Aid

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer+ Search the Manuscript Collection (Finding Aids) Collection 4-2018 LG MS 35 Ryan Conrad Collection Finding Aid Katharine Renolds Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/lgbt_finding_aids Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ryan Conrad Collection, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Collection, Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine, University of Southern Maine Libraries. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer+ Collection at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Search the Manuscript Collection (Finding Aids) by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JEAN BYERS SAMPSON CENTER FOR DIVERSITY IN MAINE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANSGENDER, QUEER+ COLLECTION RYAN CONRAD COLLECTION LG MS 35 Total Boxes: 2 Mapcase Drawers: 1 Linear Feet: 2.25 By Katharine Renolds Thomas Portland, Maine October 2014 rev. 2018 Copyright 2014 by the University of Southern Maine 2 Administrative Information Provenance: The collection was donated by Ryan Conrad between 2007 and 2011. Ownership and Literary Rights: The Ryan Conrad Collection is the physical property of the University of Southern Maine Libraries. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the creator or his/her legal heirs and assigns. -

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore Papers, 1990-2018

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80r9txj No online items Finding Aid to the Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore Papers, 1990-2018 Finding aid prepared by Tim Wilson James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 415-557-4567 [email protected] URL: http://sfpl.org/gaylesbian 2016 Finding Aid to the Mattilda GLC 110 1 Bernstein Sycamore Papers, 1990-2018 Title: Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore Papers Date (inclusive): 1990-2018 Date (bulk): (bulk 1996-2018) Identifier/Call Number: GLC 110 Creator: Sycamore, Mattilda Bernstein Physical Description: 7 cartons, 4 oversized folders, 1 map folder(8 Cubic Feet) Contributing Institution: James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 415-557-4567 [email protected] URL: http://sfpl.org/gaylesbian Abstract: Mattilda is a writer and activist concerned with various issues within the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender communities. The major subjects include assimilation, gender, identity, and politics. The collection contains manuscripts, 'zines, published articles and books, photographs and audiovisual materials. Collection is stored onsite. Language of Material: Collection materials are in English; one item is in Italian. Conditions Governing Access The collection is available for use during San Francisco History Center hours, with photographs available during Photo Desk hours. Conditions Governing Use Copyright retained by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore Papers (GLC 110), LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library. Immediate Source of Acquisition Donated by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore in three accessions, 2010, 2011, and 2012. Sycamore donated 2 cartons of writing on October 17, 2016, and an additional 2 cartons on February 14, 2018. -

Representations of Same-Sex Love in Public History By

Representations of Same-Sex Love in Public History By Claire Louise HAYWARD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Kingston University November 2015 2 Contents Page Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 List of abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One ‘Truffle-hounding’ for Same-Sex Love in Archives 40 Chapter Two Corridors of Fear and Social Justice: Representations of Same-Sex Love in Museums 90 Chapter Three Echoes of the Past in Historic Houses 150 Chapter Four Monuments as les lieux de mémoire of Same-Sex Love 194 Chapter Five #LGBTQHistory: Digital Public Histories of Same-Sex Love 252 Conclusion 302 Appendix One 315 Questionnaire Appendix Two 320 Questionnaire Respondents Bibliography 323 3 Abstract This thesis analyses the ways in which histories of same-sex love are presented to the public. It provides an original overview of the themes, strengths and limitations encountered in representations of same-sex love across multiple institutions and examples of public history. This thesis argues that positively, there have been many developments in archives, museums, historic houses, monuments and digital public history that make histories of same-sex love more accessible to the public, and that these forms of public history have evolved to be participatory and inclusive of margnialised communities and histories. It highlights ways that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans*, Queer (LGBTQ) communities have contributed to public histories of same-sex love and thus argues that public history can play a significant role in the formation of personal and group identities. It also argues that despite this progression, there are many ways in which histories of same-sex love remain excluded from, or are represented with significant limitations, in public history. -

Queer Fun, Family and Futures in Duckie's Performance Projects 2010

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Queer fun, family and futures in Duckie’s performance projects 2010-2016 Benjamin Alexander Walters Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Drama Queen Mary University of London October 2018 2 Statement of originality I, Benjamin Alexander Walters, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 27 September 2018 3 Acknowledgements This research was made possible by a Collaborative Doctoral Award from the Arts and Humanities Reseach Council (grant number AH/L012049/1), for which I am very grateful. -

Columbia Human Rights Law Review Vol

COLUMBIA HUMAN RIGHTS LAW REVIEW THE POLITICS OF LGBT RIGHTS IN ISRAEL AND BEYOND: NATIONALITY, NORMATIVITY, AND QUEER POLITICS Aeyal Gross Reprinted from Columbia Human Rights Law Review Vol. 46, No. 2 Winter 2015 COLUMBIA HUMAN RIGHTS LAW REVIEW Vol. 46, No. 2 Winter 2015 EDITORIAL BOARD 2014–2015 Editor-in-Chief Bassam M. Khawaja Executive Editor JLM Editor-in-Chief Candice Nguyen Garrett Schuman Journal Managing Executive JLM Executive Editors Production Director Managing Directors Abigail Debold Nuzhat Chowdhury Jenna Wrae Long John Goodwin Philip Tan David Imamura Executive Managing Director JLM Managing Journal Articles Alison Borochoff-Porte Director Editors Anthony Loring Kate Ferguson Ryan Gander JLM Executive Articles Billy Monks Editor Audrey Son Miles Kenyon Holly Stubbs Ethan Weinberg JLM Articles Editors Kathleen Farley Journal Executive Daniel Pohlman Notes Editor Patrick Ryan Shadman Zaman Carolyn Shanahan Prateek Vasireddy Journal Executive Submissions Editor Executive SJLM Editor Joseph Guzman Eric Lopez Journal Notes and JLM Executive State Submissions Editors Supplements Editor Victoria Gilcrease-Garcia Francis White Katherine Kettle Jessica Rogers JLM Pro Bono Rachel Stein Coordinator Caitlyn Carpenter COLUMBIA HUMAN RIGHTS LAW REVIEW Vol. 46, No. 2 Winter 2015 STAFF EDITORS Liwayway Arce Daniel Huang Keerthana Nimmala Mahfouz Basith Jonathan Jonas Claire O’Connell Christopher Bonilla Kassandra Jordan Elizabeth Parvis David Bowen Angelica Juarbe Daniel Ravitz Mark Cherry Solomon Kim Alisa Romney Allen Davis Kathleen Kim Nerissa Schwarz Lydia Deutsch Jason Lebowitz Benjamin Schwarz Daniel Donadio Sarah Lee Ben Setel Caroline Dreyspool Demi Lorant Dana Sherman Nathaneel Ducena Abigail Marion Maxwell Silverstein Alexander Egerváry Brett Masters Andrew Simpson Amy Elmgren Veronica Montalvo Sarah Sloan Arya Goudarzi Kate Morris Nicholas Spar Whitney Hood Nigel Mustapha Nina Sudarsan Luis Gabriel Hoyos Woon Jeong Nam Callie Wells Nelson Hua Cady Nicol Nicholas Wiltsie Joseph Niczky Brian Yin BOARD OF ADVISORS Mark Barenberg Kinara Flagg Sarah M. -

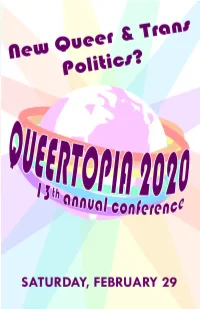

Queertopia Is Organized by Northwestern University's Queer

1 PROGRAM 8:00 — Check-in and Breakfast 9:00 AM Kresge 1525 9:00 — Opening Remarks 9:15 AM Kresge 1515 Keynote by Kim L. Hunt 9:15 — Executive Director of Pride Action Tank 10:15 AM Kresge 1515 Panel 1A: Activism, Panel 1B: The Politics of 10:30 — Abolition, and Visions of Queer Health 2:00 PM Queer and Trans Justice Kresge 2339 Kresge 2343 12:00 — Lunch Break 1:00 PM Kresge 2415 Panel 2A: Politics, Panel 2B: Technologies 1:00 — Performance, and and Transformations of 2:30 PM Resistance in Queer Media Queer Spaces and Places Kresge 2339 Kresge 2343 2:30 — Coffee Break 3:00 PM Kresge 2415 Criminal Queers 3:00 — Screening and Panel Discussion 5:00 PM Kresge 1515 5:00 — Closing Remarks 5:10 PM Kresge 1515 Reception (Open to All) 5:10 PM Kresge 2415 2 ACCESSIBILITY INFORMATION BUILDING ACCESS Is there a ramp, elevator, and/or wheelchair lift to get into the building? Yes, an accessible entrance is available at the front of the building (Kresge Hall, 1880 Campus Drive). Please take the elevator down to Floor 1 for check-in. Is accessible parking available? Parking is not available directly next to the event space. The closest parking lot is the Locy Lot located at 1850 Campus Drive. The lot is a 2-minute walk to Kresge, and the parking lot has designated accessible spaces. SEATING ACCESS Once inside the building, how does one get to the event rooms? All conference activities will occur on the first and second floors of Kresge Hall. -

Phd, Concordia University, Interdisciplinary Humanities Program, in Progress

Ryan Conrad [email protected] www.faggotz.org Education: • PhD, Concordia University, Interdisciplinary Humanities Program, in progress. • MFA, Maine College of Art, Interdisciplinary Studio Program, 2010. Thesis Paper: Reviving the Queer Political Imagination. Thesis Exhibition: Cruising the Cartography. • B.A., Bates College, Department of Political Science and Department of Theater, 2005. Honors Thesis Paper: Art. Culture. Work. Recent & Upcoming Publications: Books/Catalogs • Against Equality: Prisons Will Not Protect You, editor, (AE Press), October 2012. • Disastrous Inclusion: Critical Reflections on the Legacy of DADT, guest editor, We Who Feel Differently Journal, No. 2, May 2012. • Against Equality: Don’t Ask to Fight Their Wars, editor, (AE Press), October 2011. • Against Equality: Queer Critiques of Gay Marriage, editor, (AE Press), September 2010. • Reviving the Queer Political Imagination, (Moth Press) Portland ME, 9 May 2010. • Future of the Past: Reviving the Queer Archives (Moth Press) Portland ME, 5 June 2009. • Out of the Closets and Into the Libraries, 2nd edition (Bangarang), April 2009. • Out of the Closets and Into the Libraries, 1st edition, (Bangarang), May 2005. Anthology Chapters • “That’s Right, We’re Here to Destroy Marriage!,” The Gay Agenda: Claiming Space, Identity, and Justice, forthcoming anthology, 2013. • “(Gay) Marriage and (Queer) Love,” Queering Anarchism (AK Press), forthcoming anthology, Fall 2012. Articles/Essays • “Against Equality: Don’t Ask to Fight Their Wars,” Fifth Estate Magazine, Vol. 47, No. 2, Spring 2012. • “This is Progress? Critical reflections on the repeal of DADT,” Out In Maine, Spring 2012. • “Forget Equality, I Want Justice!,” Out in Maine, June 2011. • “Against Equality: Defying Inclusion, Demanding Transformation in the U.S. -

The Israeli Queerhana: Time-Space of Subversion and Future Utopia

The Israeli Queerhana: Time-Space of Subversion and Future Utopia Avner Rogel* Hebrew University of Jerusalem In this article, I argue that the Queerhana parties held in the early 2000s in Israel can be seen as queer time-spaces. In the local context, this aspect of the Queerha- nas was deeply subversive not only of the heteronormative order, but also of the homonormative and the homonational. In turn, I argue, that Queerhana offered new spatial forms such as erotic hybrid space, and new temporal concepts such as erotic transcendent time. These configurations offered utopian and futuristic queer embodiments of another possible social life of diversity and coexistence. The discussion contextualizes the Queerhana parties in relation to theories of queer time-space based on content analysis of the parties, as well as interviews with key former party activists. Keywords: queer geography, time-space, parties, activism, performance, drag, fu- ture, utopia, Israel/Palestine INTRODUCTION "The idea of creating a space that will allow us to create the better/creative/free/delusional/real world that we dream of." Queerhana Festival invitation, 2003 Queerhanas were queer parties held from 2001-2006 in Israel. Arising in protest against the agenda of the LGBT urban commodified culture embraced by the Israeli national consensus, they first emerged as free open street parties initiated by a fluid collective in a declared effort to promote queer activism. Since November 2001, several spontaneous queer parties were held, taking advantage of temporary condi- tions of disorders due to widespread renovation works, which preceded the parties officially named Queerhana but deserve to be considered part of that category in retrospect. -

Making Room for Gender and Sexual Possibility

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2020 Identity Positivity in Decolonial Worlds: Making Room for Gender and Sexual Possibility Erica Chu Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chu, Erica, "Identity Positivity in Decolonial Worlds: Making Room for Gender and Sexual Possibility" (2020). Dissertations. 3777. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2020 Erica Chu LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO IDENTITY POSITIVITY IN DECOLONIAL WORLDS: MAKING ROOM FOR GENDER AND SEXUAL POSSIBILITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY ERICA CHU CHICAGO, IL MAY 2020 Copyright by Erica Chu, 2020 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS After years of white Evangelical Christian education, indoctrination, and repression, I moved to Chicago in 2006 to start graduate school. Upon arriving, I met up with a friend who came out to me and told me a story about his faith that made me realize I’d been judging others and myself too harshly. I started coming out to people as queer and then fell in love. What came after was a flood of life changes; broken and severely damaged relationships with family, friends, and communities; self-discovery, trauma, healing, and exploration; religious changes, alienation, distress, and worldviews shaken and then shaken again.