This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a Bible Verses

Goal and source in South American languages Emilia Roosvall Department of Linguistics Bachelor’s Programme in Linguistics 180 ECTS credits Spring semester 2020 Supervisor: Bernhard Wälchli Swedish title: Mål och källa i sydamerikanska språk Goal and source in South American languages Emilia Roosvall Abstract This study primarily investigates the expression of two local roles, goal and source, inSouth American languages. Local roles describe the direction of movement or locatedness in relation to a physical object, a ground, in a motion event. While goal expresses motion to or towards and source expresses motion from a ground, these are not always distinguished from one another but sometimes encoded indifferently. A previous cross-linguistic study by Wälchli and Zúñiga (2006) shows that the encoding of goal and source tends to be distinct in Eurasia, North Africa, and Australia, and more diverse in the Americas and New Guinea. However, the sample used in their study is not representative in the Americas. The principal aim of the present study is to determine whether the encoding of goal and source is distinct or indifferent in a representative sample of South American languages, using both reference grammars and parallel texts consisting of Bible translations. The local role path, expressing motion through a ground, is also studied to the extent that this is possible given the data. The findings show that distinct encoding of goal and source is most common in the sample. Indifferent languages are still attested for, yet to a smaller extent than in Wälchli and Zúñiga’s study(2006). Keywords goal, source, South American languages, motion events, linguistic typology Sammanfattning Denna studie undersöker främst uttryck av två lokalroller, mål och källa, i sydamerikanska språk. -

Zaparoan Negation Revisited1 Negação Em Záparo Revisitada Johan Van Der Auwera 2 Olga Krasnoukhova3

Artigos • Articles Zaparoan negation revisited1 Negação em Záparo revisitada Johan van der Auwera 2 Olga Krasnoukhova3 DOI 10.26512/rbla.v11i02.27300 Recebido em setembro/2019 e aceito em outubro/2019. Abstract The paper revisits negation in the Zaparoan languages Arabela, Iquito and Záparo. For Iquito, which exhibits single, double as well as triple negation, we adopt a Jespersen Cycle perspective and for Záparo and Arabela it is the Negative Existential Cycle which proves enlightening. We speculate that both in Iquito and Záparo there is a diachronic link between the formal expression of negation and the concept of ‘leaving’. We address the internal subclassification of the Zaparoan languages, showing that, at least for the structural feature of negation, the position of Arabela is closer to Záparo than to Iquito. Key words: Zaparoan. Standard negation. Existential negation. Prohibitives. Jespersen Cycle. Negative Existential Cycle. Resumo O artigo revisita a negação nas línguas Záparo Arabela, Iquito e Záparo. Para Iquito, que exibe negação única, dupla e tripla, adotamos a perspectiva do Ciclo de Jespersen e, para Záparo e Arabela, é o Ciclo Existencial Negativo que se mostra esclarecedor. Hipotetizamos que tanto em Iquito quanto em Záparo existe um vínculo diacrônico entre a expressão 1 This paper emanates from a larger project on the typology of negation in the indigenous languages of South America, supported by the Research Foundation Flanders. We are grateful to Joshua Birchall (Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi, Belém), Cynthia Hansen (Grinnell College, Iowa), and Lev Michael (UC Berkeley) for comments on earlier versions of the paper. We follow the orthography and the glossing of the sources as closely as possible. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-215 (Salt Lake City, Utah) Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 215 (Salt Lake City, Utah) Aktiengesellschaft Trial, Nuremberg, I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-225 (Colo.) Germany, 1947-1948 USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 225 (Colo.) Subsequent proceedings, Nuremberg War Corridor (Ill.) I-244 (Tulsa, Okla.) Crime Trials, case no. 6 I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 244 (Tulsa, Okla.) BT Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-255 (Ill. and Mo.) Germany, 1946-1949 I-5 USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-H-3 (Hawaii) USE Interstate 5 I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) USE Interstate H-3 (Hawaii) I-8 (Ariz. and Calif.) USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-hadja (African people) USE Interstate 8 (Ariz. and Calif.) I-270 (Md.) USE Kasanga (African people) I-10 USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I Ho Yüan (Beijing, China) USE Interstate 10 I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE Interstate 15 I-291 (Conn.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 291 (Conn.) I-hsing ware USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-394 (Minn.) USE Yixing ware I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-K'a-wan Hsi (Taiwan) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Qijiawan River (Taiwan) I-17 USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE Interstate 17 I-405 (Wash.) UF Gilbertese I-19 (Ariz.) USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Interstate 19 (Ariz.) I-470 (Ohio and W. -

Preliminary Correspondences and the Status of Omurano

On Záparoan as a valid genetic unity: Preliminary correspondences and the status of Omurano Fernando O. de Carvalho1 Abstract The Záparoan linguistic family has been so far acknowledged as constituting a genetic group only on the basis of lexical similarity and grammatical parallels. We present here a preliminary statement of recurring sound correspondences holding among the basic lexical and grammatical vocabularies of three languages usually seen as belonging into the Záparoan family: Iquito, Arabela and Záparo. Though still a preliminary effort towards a more complete understanding of the history of this group, this is enough to gain some insight into the sound changes that have acted in the diversification of these languages from their putative common ancestor and to qualify the claims concerning the Záparoan affiliation of a fourth language, Omurano, our conclusion being that no evidence for this hypothesis exists. Keywords: Záparoan languages. Reconstruction. Comparative Method. Resumo A família linguística Záparo é reconhecida como tal, até o momento, com base somente em similaridades lexicais e alguns paralelos gramaticais. Apresentamos aqui um conjunto de correspondências sonoras regulares encontradas nos vocabulários lexicais e em itens gramaticais das três línguas usualmente apontadas como constituindo essa família: o Iquito, o Arabela e o Záparo. Embora este seja ainda um esforço preliminar em direção a uma caracterização mais completa da história dessa família, há fundamentos mais do que suficientes para avançar a nossa compreensão das mudanças sonoras que atuaram na diversificação dessas línguas a partir do seu ancestral comum e para qualificar afirmações presentes na literatura acerca da filiação de uma quarta língua à família Záparo, o Omurano. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) UF Gilbertese I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-270 (Md.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I-Kiribati language Corridor (Ill.) I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Gilbertese language I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I kuan tao (Cult) USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-394 (Minn.) USE Yi guan dao (Cult) I-5 USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I language USE Interstate 5 I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Yi language I-10 USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-li Ho (China and Kazakhstan) USE Interstate 10 I-405 (Wash.) USE Ili River (China and Kazakhstan) I-15 USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) I-li-mi (China) USE Interstate 15 I-470 (Ohio and W. Va.) USE Taipa Island (China) I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 470 (Ohio and W. Va.) I-liu District (China) USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-476 (Pa.) USE Yiliu (Guangdong Sheng, China : Region) I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Blue Route (Pa.) I-liu Region (China) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-478 (New York, N.Y.) USE Yiliu (Guangdong Sheng, China : Region) I-17 USE Westway (New York, N.Y.) I-liu ti-chʻü (China) USE Interstate 17 I-495 (Mass.) USE Yiliu (Guangdong Sheng, China : Region) I-19 (Ariz.) USE Interstate 495 (Mass.) I love you (The American Sign Language phrase) USE Interstate 19 (Ariz.) I-495 (Md. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-225 (Colo.) Germany, 1947-1948 USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 225 (Colo.) Subsequent proceedings, Nuremberg War I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-244 (Tulsa, Okla.) Crime Trials, case no. 6 USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 244 (Tulsa, Okla.) BT Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, Corridor (Ill.) I-255 (Ill. and Mo.) Germany, 1946-1949 I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-H-3 (Hawaii) USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) USE Interstate H-3 (Hawaii) I-5 USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-hadja (African people) USE Interstate 5 I-270 (Md.) USE Kasanga (African people) I-8 (Ariz. and Calif.) USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I Ho Yüan (Beijing, China) USE Interstate 8 (Ariz. and Calif.) I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-10 USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE Interstate 10 I-291 (Conn.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 USE Interstate 291 (Conn.) I-hsing ware USE Interstate 15 I-394 (Minn.) USE Yixing ware I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-K'a-wan Hsi (Taiwan) USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Qijiawan River (Taiwan) I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-405 (Wash.) UF Gilbertese I-17 USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Interstate 17 I-470 (Ohio and W. -

33 Linguistic Areas, Linguistic Convergence and River Systems in South America

33 Linguistic Areas, Linguistic Convergence and River Systems in South America Rik van Gijn, Harald Hammarström, Simon van de Kerke, Olga Krasnoukhova and Pieter Muysken 33.1 Introduction The linguistic diversity of the South American continent is quite impress- ive. There are 576 indigenous languages attested (well enough documen- ted to be classified family-wise), of which 404 are not yet extinct. There are 56 poorly attested languages (which nevertheless were arguably not the same as any of the 576), of which three are known to be not yet extinct (Nordhoff et al. 2013). Furthermore, there are 71 uncontacted living tribes, mainly in Brazil, which may speak anywhere between zero and 71 lan- guages different from those mentioned (Brackelaire and Azanha 2006). Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the linguistic diversity of South American indigenous languages is their genealogical diversity. The languages fall into some 65 isolates and 44 families (Campbell 2012a; Nordhoff et al. 2013), based on a comparison of basic vocabulary. Nearly all of the families show little internal diversity, indicative of a shallow time depth. Alongside this picture of genealogical diversity, many areal specialists have noted the widespread occurrence of a number of linguistic features across language families, suggesting either sustained contacts between groups of people or remnants from times when the situation in South America may have been genealogically more homogeneous. We only have historical records going back about 500 years, and the archaeological record is scanty and fragmentary (Eriksen 2011). It follows that there are large tracts of South American prehistory that are unknown. Areal-typological analysis aims to address this gap by finding out which languages have been in contact and how, as evidenced by their typological Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

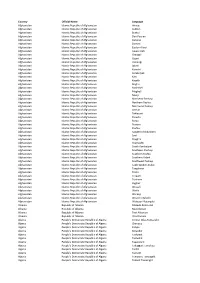

Missing Languages

Country Official Name Language Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Aimaq Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ashkun Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Brahui Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Dari Persian Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Darwazi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Domari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Eastern Farsi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gawar-Bati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Grangali Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gujari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Hazaragi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Jakati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kamviri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Karakalpak Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kazakh Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kirghiz Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Malakhel Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Mogholi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Munji Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northeast Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northern Pashto Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northwest Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ormuri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Pahlavani Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parachi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parya Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Prasuni Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan -

The Indigenous Languages of South America WOL 2

The Indigenous Languages of South America WOL 2 Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 The World of Linguistics Editor Hans Henrich Hock Volume 2 De Gruyter Mouton Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 The Indigenous Languages of South America A Comprehensive Guide Edited by Lyle Campbell Vero´nica Grondona De Gruyter Mouton Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3 e-ISBN 978-3-11-025803-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The indigenous languages of South America : a comprehensive guide / edited by Lyle Campbell and Vero´nica Grondona. p. cm. Ϫ (The world of linguistics; 2) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of South America Ϫ Languages. 2. Endangered lan- guages. 3. Language and culture. I. Campbell, Lyle. II. Gron- dona, Vero´nica Marı´a. PM5008.I53 2012 498Ϫdc23 2011042070 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ” 2012 Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Thinkstock/iStockphoto Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ϱ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 camp_000.pod v 07-10-13 10:05:11 -mu- mu Table of contents Preface Lyle Campbell and Verónica Grondona .................. -

Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison

Language Dynamics and Change 4 (2014) 167–187 brill.com/ldc Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison Harald Hammarström Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics & Centre for Language Studies, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, The Netherlands [email protected] Mark Donohue Department of Linguistics, Australian National University, Australia [email protected] Abstract While the notion of the ‘area’ or ‘Sprachbund’ has a long history in linguistics, with geographically-defined regions frequently cited as a useful means to explain typolog- ical distributions, the problem of delimiting areas has not been well addressed. Lists of general-purpose, largely independent ‘macro-areas’ (typically continent size) have been proposed as a step to rule out contact as an explanation for various large-scale linguistic phenomena. This squib points out some problems in some of the currently widely-used predetermined areas, those found in the World Atlas of Language Struc- tures (Haspelmath et al., 2005). Instead, we propose a principled division of the world’s landmasses into six macro-areas that arguably have better geographical independence properties. Keywords areality – macro-areas – typology – linguistic area 1 Areas and Areality The investigation of language according to area has a long tradition (dating to at least as early as Hervás y Panduro, 1971 [1799], who draws few historical © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2014 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00401001 168 hammarström and donohue conclusions, or Kopitar, 1829, who is more interested in historical inference), and is increasingly seen as just as relevant for understanding a language’s history as the investigation of its line of descent, as revealed through the application of the comparative method.