Moving on the Globe Issues of Mobility and Migration in a Globalized World As Depicted in Films of the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Results FY 2019/2020

Annual results FY 2019/2020 Operating margin rate at 31%, increasing significantly compared with previous fiscal years Continued decrease in overheads : new drop of €14 M compared with 2018/2019 overheads, which were already €7 M lower than the previous fiscal year Net result of €(95) M, mainly due to non-recurring items linked to the restructuring : exceptional result of €(64) M including €(60) M with no cash impact Finalization of the financial restructuring with the completion after closing of the share capital increases reserved for the Vine and Falcon funds for €193 M Saint-Denis, 29 July 2020 – EuropaCorp, one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, film producer and distributor, reports its annual consolidated income, which ended on 31 March 2020, as approved by the Board of Directors at its meeting on 28 July 2020. Presentation IFRS 5* Profit & Loss – € million 31 March 2019 31 March 2020 Var. 31 March 2019 31 March 2020 Var. Revenue 150,0 69,8 -80,2 148,7 69,8 -78,9 Cost of sales -121,6 -48,3 73,3 -121,4 -48,3 73,1 Operating margin 28,4 21,4 -6,9 27,3 21,4 -5,8 % of revenue 19% 31% 18% 31% Operating income -79,0 -59,1 19,9 -71,2 -59,1 12,1 % of revenue -53% -85% -48% -85% 0 Net Income -109,9 -95,1 14,8 -109,9 -95,1 14,8 % of revenue -73% -136% -74% -136% * To be compliant with IFRS 5, the activity related to the exploitation of the catalog Roissy Films, sold in March 2019, has been restated within the consolidated FY 2018/19 for a better comparison. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Liste Dvd Consult

titre réalisateur année durée cote Amour est à réinventer (L') * 2003 1 h 46 C 52 Animated soviet propaganda . 1 , Les impérialistes américains * 1933-2006 1 h 46 C 58 Animated soviet propaganda . 2 , Les barbares facistes * 1941-2006 2 h 16 C 56 Animated soviet propaganda . 3 , Les requins capitalistes * 1925-2006 1 h 54 C 59 Animated soviet propaganda . 4 , Vers un avenir brillant, le communisme * 1924-2006 1 h 54 C 57 Animatix : une sélection des meilleurs courts-métrages d'animation française. * 2004 57 min. C 60 Animatrix * 2003 1 h 29 C 62 Anime story * 1990-2002 3 h C 61 Au cœur de la nuit = Dead of night * 1945 1 h 44 C 499 Autour du père : 3 courts métrages * 2003-2004 1 h 40 C 99 Avant-garde 1927-1937, surréalisme et expérimentation dans le cinéma belge * 1927-1937 1 h 30 C 100 (dvd 1&2) Best of 2002 * 2002 1 h 12 C 208 Caméra stylo. Vol. 1 * 2001-2005 2 h 25 C 322 Cinéma différent = Different cinema . 1 * 2005 1 h 30 C 461 Cinéma documentaire (Le) * 2003 2 h 58 C 462 Documentaire animé (Le). 1, C'est la politique qui fait l'histoire : 9 films * 2003-2012 1 h 26 C 2982 Du court au long. Vol. 1 * 1973-1986 1 h 52 C 693 Fellini au travail * 1960-1975 3 h 20 C 786 (dvd 1&2) Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. 01 * 1947-1984 2 h 40 C 3176 Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. -

71 Ans De Festival De Cannes Karine VIGNERON

71 ans de Festival de Cannes Titre Auteur Editeur Année Localisation Cote Les Années Cannes Jean Marie Gustave Le Hatier 1987 CTLes (Exclu W 5828 Clézio du prêt) Festival de Cannes : stars et reporters Jean-François Téaldi Ed du ricochet 1995 CTLes (Prêt) W 4-9591 Aux marches du palais : Le Festival de Cannes sous le regard des Ministère de la culture et La 2001 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Mar sciences sociales de la communication Documentation française Cannes memories 1939-2002 : la grande histoire du Festival : Montreuil Média 2002 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can l’album officiel du 55ème anniversaire business & (Exclu du prêt) partners Le festival de Cannes sur la scène internationale Loredana Latil Nouveau monde 2005 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) LAT Cannes Yves Alion L’Harmattan 2007 Magasin W 4-27856 (Exclu du prêt) En haut des marches, le cinéma : vitrine, marché ou dernier refuge Isabelle Danel Scrineo 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) DAN du glamour, à 60 ans le Festival de Cannes brille avec le cinéma Cannes Auguste Traverso Cahiers du 2007 Salle Santeuil 791 (44) Can cinéma (Exclu du prêt) Hollywood in Cannes : The history of a love-hate relationship Christian Jungen Amsterdam 2014 Magasin W 32950 University press Sélection officielle Thierry Frémaux Grasset 2017 Magasin W 32430 Ces années-là : 70 chroniques pour 70 éditions du Festival de Stock 2017 Magasin W 32441 Cannes La Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes : cinéma en liberté (1969- Ed de la 1993 Magasin W 4-8679 1993) Martinière (Exclu du prêt) Cannes, cris et chuchotements Michel Pascal -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Here Was Obviously No Way to Imagine the Event Taking Place Anywhere Else

New theatre, new dates, new profile, new partners: WELCOME TO THE 23rd AND REVAMPED VERSION OF COLCOA! COLCOA’s first edition took place in April 1997, eight Finally, the high profile and exclusive 23rd program, years after the DGA theaters were inaugurated. For 22 including North American and U.S Premieres of films years we have had the privilege to premiere French from the recent Cannes and Venice Film Festivals, is films in the most prestigious theater complex in proof that COLCOA has become a major event for Hollywood. professionals in France and in Hollywood. When the Directors Guild of America (co-creator This year, our schedule has been improved in order to of COLCOA with the MPA, La Sacem and the WGA see more films during the day and have more choices West) decided to upgrade both sound and projection between different films offered in our three theatres. As systems in their main theater last year, the FACF board an example, evening screenings in the Renoir theater made the logical decision to postpone the event from will start earlier and give you the opportunity to attend April to September. The DGA building has become part screenings in other theatres after 10:00 p.m. of the festival’s DNA and there was obviously no way to imagine the event taking place anywhere else. All our popular series are back (Film Noir Series, French NeWave 2.0, After 10, World Cinema, documentaries Today, your patience is fully rewarded. First, you will and classics, Focus on a filmmaker and on a composer, rediscover your favorite festival in a very unique and TV series) as well as our educational program, exclusive way: You will be the very first audience to supported by ELMA and offered to 3,000 high school enjoy the most optimal theatrical viewing experience in students. -

Ancient Greek Myth and Drama in Greek Cinema (1930–2012): an Overall Approach

Konstantinos KyriaKos ANCIENT GREEK MYTH AND DRAMA IN GREEK CINEMA (1930–2012): AN OVERALL APPROACH Ι. Introduction he purpose of the present article is to outline the relationship between TGreek cinema and themes from Ancient Greek mythology, in a period stretching from 1930 to 2012. This discourse is initiated by examining mov- ies dated before WW II (Prometheus Bound, 1930, Dimitris Meravidis)1 till recent important ones such as Strella. A Woman’s Way (2009, Panos Ch. Koutras).2 Moreover, movies involving ancient drama adaptations are co-ex- amined with the ones referring to ancient mythology in general. This is due to a particularity of the perception of ancient drama by script writers and di- rectors of Greek cinema: in ancient tragedy and comedy film adaptations,3 ancient drama was typically employed as a source for myth. * I wish to express my gratitude to S. Tsitsiridis, A. Marinis and G. Sakallieros for their succinct remarks upon this article. 1. The ideologically interesting endeavours — expressed through filming the Delphic Cel- ebrations Prometheus Bound by Eva Palmer-Sikelianos and Angelos Sikelianos (1930, Dimitris Meravidis) and the Longus romance in Daphnis and Chloë (1931, Orestis Laskos) — belong to the origins of Greek cinema. What the viewers behold, in the first fiction film of the Greek Cinema (The Adventures of Villar, 1924, Joseph Hepp), is a wedding reception at the hill of Acropolis. Then, during the interwar period, film pro- duction comprises of documentaries depicting the “Celebrations of the Third Greek Civilisation”, romances from late antiquity (where the beauty of the lovers refers to An- cient Greek statues), and, finally, the first filmings of a theatrical performance, Del- phic Celebrations. -

Issue #72 Summer / Fall 2008 Lars Bloch Interview (Part 2) a Man, a Colt the MGM Rolling Road Show Latest DVD Reviews

Issue #72 Summer / Fall 2008 Lars Bloch Interview (part 2) A Man, a Colt The MGM Rolling Road Show Latest DVD Reviews WAI! #72 THE SWINGIN’ DOORS April and May were months that took a number of well known actors of the Spaghetti western genre: Jacques Berthier, Robert Hundar, John Phillip Law and Tano Cimarosa were all well known names in the genre. Of course we should expect as much since these people are now well into their 70s and even 80s. Still in our minds they are young vibrant actors who we see over and over again on video and DVD. It’s hard to realize that it’s been 40+ years since Sergio Leone kicked off the Spaghetti western craze and launched a world wide revolution in film that we still see influencing films today. Hard to believe Clint Eastwood turned 78 on May 30th. Seems like only yesterday he was the ‘Man with No Name’ and starring in the first of the Leone films that launched the genre. Remember when Clint was criticized so badly as an actor and for the films he appeared in during the 60s and 70s. Now he’s revered in Hollywood because he’s outlived his critics. I guess we recognized a real star long before the critics did. A great idea came to Tim League’s mind in the launching of the “Rolling Road Show”, where films are actually shown where they were filmed. I wasn’t able to travel to Spain to see the Dollars trilogy but we have a nice review of the films and the experience by someone who was there. -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

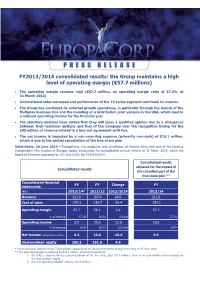

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue