EOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 787 UD 011 129 Anzalcne, JS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Welcome

PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Friends, Colleagues, and Students, Welcome to the 82nd Annual Mississippi Bandmasters Association State Band Clinic in Natchez. The other members of the MBA Executive Board and I hope that you will experience growth, new perspectives, and renewed aspirations for teaching and learning music in your community during this year’s clinic. I would like to wish all of the students in attendance a heartfelt congratulations on participating in this esteemed event. You represent the very best of the students from your band programs – I encourage you to take that sentiment to heart. Thousands of students have shared in this honor for the last 82 years. Many of you will meet friends this weekend that you will have throughout your life. Lastly, I encourage you to take this opportunity to enjoy making music with others and learning from some of the most outstanding teachers in our country. For members of our association, take the time to visit with the exhibitors and clinicians throughout the weekend. Take advantage of the clinics and presentations that are offered so that you may leave Natchez with new insights and perspectives that you can use with your students at home. Clinic is also a time to renew old friendships and foster new ones. I hope that veteran teachers will take the time to get to know those that are new to our profession and new teachers will seek out the guidance of those with more experience. To our guest clinicians, exhibitors, featured ensembles, and conductors we welcome you and hope that you will enjoy your time with us. -

Special Course and Program Offerings in Jackson Public Schools January 19, 2021 JPS Mission and Vision

Innovative Teaching and Learning for All: Special Course and Program Offerings in Jackson Public Schools January 19, 2021 JPS Mission and Vision Our mission is to develop scholars through world‐class learning experiences to attain an exceptional knowledge base, critical and relevant skill sets, and the necessary dispositions for great success. Our vision is to prepare scholars to achieve globally, to contribute locally, and to be fulfilled individually. •Equity •Excellence •Growth Mindset JPS Core •Relationships Values •Relevance •Positive and Respectful Cultures Provide an overview of special course offerings and programs in the Jackson Public School District Objectives Discuss efforts to improve and/or sustain quality courses and programs in alignment with the District’s Strategic Plan Commitments #1 – A Strong Start #2 – Innovative Teaching and Learning #5 – Joyful Learning Environments Special Course Offerings Special Course Offerings Commitment #2 – Innovative Teaching and Learning • The Open Doors‐Gifted Education Program o Identifies and serves gifted students in a uniquely qualitatively differentiated program not available in the regular classroom o Encourages and nurtures inquiry, flexibility, decision making, thinking skills, self evaluation, and divergent thinking o Serves intellectually gifted students in grades 2‐8 • Strings in Schools o Continued collaboration with the MS Symphony Orchestra o Impacts over 3,000 students in grades 3‐12 through ensemble visits, informances, full orchestra educational concerts, and string instrument -

The President

Jackson State University Office of the President October 22, 2015 Dear Notable Alumni Panelist: As a leader in your profession, you serve as a beacon of light to our students as they embrace the global and mobile learning opportunities here at Jackson State University. Your panel discussions with alumni and students are gateways for student and alumni networking as well as to connecting our students to real world experiences and successes. The President By your participation, you demonstrate to our students and alumni the many positive impacts of a JSU education. Thank you for giving back in this special way to your “dear old college home” during this Homecoming 2015 celebration. Let the good times roar. Sincerely, Carolyn W. Meyers President 1 Table of Contents Letter from JSU President ....................................................................................................................................................................1 Letter from JSUNAA President ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Letter from Director of Alumni and Constituency Relations ..................................................................................4 Letter from PAC President ...................................................................................................................................................................5 Council of Deans .......................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

01/07/2020 – 2018 JPS Bond Construction Program

JPS Board of Trustees Bond Update 1.7.2020 JPS Bond Construction Program Facts: Bond Program Phase I Schools High Schools Middle Schools • Callaway High School* • Bailey APAC Middle School* • Forest Hill High School* • Hardy Middle School • Jim Hill High School* • Lanier High School • Murrah High School • Provine High School* • Requesting Clearance Approval • Wingfield High School* From MDE JPS Bond Construction Program Facts: Bond Program Phase I Schools Elementary Schools Other Academic Facilities • Boyd Elementary School* • Career Development Center • Green Elementary School • Capital City Alternative School • Wilkins Elementary School* • Performing Arts Center • Van Winkle Elementary School* • JROTC * Mississippi Department of Education • Requesting Clearance Approval From MDE Corrective Action Plan (CAP) Projects Completed to Date - 42 - (42 – Total projects completed to date including 12 projects completed since December 3, 2019 Board meeting update) School Project Green Elementary 27 spaces added for employee parking. Front entrance and walkway were repaired to complete the requirements of the Mississippi Department of Wilkins Elementary Education ‘s Corrective Action Plan (CAP). Handicap ramp was repaired to meet ADA requirements. Hardy Middle Drainage pipe scanned in preparation for site drainage improvements in the courtyard and exterior of the school. Projects Completed to Date School Project Science lab decommissioned to complete the requirements of the Mississippi Department of Education’s Callaway High Corrective Action Plan. Phase I of exterior improvements completed which included building pressure washing in preparation for Callaway High building façade upgrade. Callaway High Sewer line replaced in preparation of restroom renovations. Callaway High Courtyard fencing replaced to provide a more secured environment between buildings “B” and “C.” Science lab decommissioned to complete the requirements of the Mississippi Department of Education’s Forest Hill High Corrective Action Plan. -

Johnny B. Gilleylen Sr., Phd

J O H N N Y B . G I L L E Y L E N S R . 1700 SUZANNA DRIVE, RAYMOND, MS 39154 TEL: (601) 372-1660 • E-MAIL: [email protected] EDUCATION 1997 Ph. D., Public Policy and Public Administration Major: Program Management and Policy Analysis Jackson State University Jackson, Mississippi 1992 M.S. Manufacturing Management Kettering University (Formerly General Motors Institute) Flint, Michigan 1976 Post-Graduate Studies Field: Biology Kent State University Warren, Ohio 1975 Post-Graduate Studies Field: Economics Youngstown State University Youngstown, Ohio 1973 B.S. Mathematics Tougaloo College Tougaloo, Mississippi 1969 Diploma West Amory High School Amory, Mississippi SKILLS Program Evaluation (40 years of experience) Summative and formative evaluations Innovative and Continuous Improvement Methodologies Certifications Six Sigma Master Black Belt (Continuous improvement) Shanin Red X Technician (Problem solving) Value Analysis Engineering (Value creation) Software Expertise ArcGIS (Geographical Information Systems) SPSS (Statistical) Microsoft Office Suite (Word, Excel, Access, PowerPoint, Publisher, One Note) Mendeley (Document Manager) Adobe Acrobat XI Pro (including Form Central) TREDIS (Transportation Economic Impact Analysis) Johnny B. Gilleylen Sr., PhD PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Jackson State University (15 years) Chair, Department of Public Policy and Administration Interim Chair, Department of Public Policy and Administration Interim Executive Director, School of Policy and Planning Associate Professor and Interim Program Director, Public -

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians January 2020 1 January 2020 Prepared by NSPARC / A unit of Mississippi State University 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary...............................................................................................................................1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Institutional Profile...............................................................................................................................4 Student Enrollment...............................................................................................................................6 Community College Graduates.............................................................................................................9 Employment and Earnings Outcomes of Graduates..........................................................................11 Impact on the State Economy.............................................................................................................13 Appendix A: Workforce Training.........................................................................................................15 Appendix B: Degrees Awarded............................................................................................................16 -

Excellence for All: JPS Course and Special

Graduation 2021 Presented by: Laketia Marshall-Thomas, Ed.S. March 22, 2021 OBJECTIVE To provide an overview of the district's graduation plans for the Class of 2021 OVERVIEW JPS high schools will hold commencement ceremonies for graduating seniors on Tuesday, June 1, 2021, and Wednesday, June 2, 2021, at the Mississippi Coliseum located at 1207 Mississippi Street in Jackson, MS. To decrease the number of individuals in the Mississippi Coliseum at one time, each school will host 2-3 commencement ceremonies, depending on its graduating class size. GRADUATION 2021 To adhere to COVID-19 safety regulations and protocols and to provide the safest environment for our graduates, staff, and families/friends; each graduating senior will be given four (4) tickets for families and friends to attend the commencement ceremony. Each ticket will admit one person and must be presented at the time of entrance into the coliseum. *We respectfully ask that all graduates and visitors leave the coliseum immediately after the ceremony to allow time for cleaning and sanitizing in preparation for the next ceremony. TUESDAY, June 1, 2021 School Group Time Murrah High School Group 1: 8:30 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. Commencement Group 2: 10:00 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. Schedule Group 3: 11:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. Provine High School Group 1: 1:30 p.m. – 2:30 p.m. Group 2: 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. Jim Hill High School Group 1: 5:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m. Group 2: 6:30 p.m. -

Advertising Ad for Bid 3175 Forest Hill H S Performance Arts Renovations

Jackson Public School District Business Office Post Office Box 2338 Jackson, Mississippi Telephone: 960-8799 Fax Number: 960-8967 ADVERTISEMENT REQUEST Name: Company: Fax No. Mary or Caroline Clarion-Ledger 601-961-7033 or 1-888-516-9220 ext. 3302 Katrina Jackson Advocate 601-948-4122 Jackie Hampton Mississippi Link 601-368-8481 LaTisha Landing MS Development Authority 601-359-5290 Acct. 212327 P. O. 545514 - The Clarion-Ledger P. O. 545512 - Jackson Advocate P. O. 545513 - Mississippi Link Notice: Please Email Invoices electronically for Payments to Bettie Jones @ [email protected] and CC: Adatisha Evans at [email protected]. Proof of Publications are to be mailed to JPSD Attention: Bettie Jones Clarion Ledger March 02, 2021 and March 09, 2021 Jackson Advocate March 05, 2021 and March 12, 2021 MS Link: March 05, 2021 and March 12, 2021 Date/Time April 09, 2021 @ 10:00 A.M. (Local Prevailing Time) Bid 3175 Forest Hill High School Performance Arts Renovation I hereby certify that the above legal ad was received. Newspaper: _______________________________ Signed: _________________________________________ Date: _________________________ Electronic Bidding Advertisement for Bid 3175 Forest Hill High School Performance Arts Renovation Sealed, written formal bid proposals for the above bid will be received by the Board of Trustees of the Jackson Public School District, in the Business Office, 662 South President Street, Jackson, Mississippi, until 10:00 A.M. (Local Prevailing Time) April 09, 2021 at which time and place they will be publicly opened and read aloud. A Pre-Bid Conference concerning the Forest Hill High School Performance Art project will be held at 2607 Raymond Road, Jackson MS 39212 on Tuesday, March 23, 2021 at 2:00 PM. -

OFFICE of CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items June 19-20, 2014 OFFICE of EDUCATOR LICENSUR

OFFICE OF CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items June 19-20, 2014 OFFICE OF EDUCATOR LICENSURE 43. Approval of appointments to the Commission on Teacher and Administrator Education, Certification and Licensure and Development Background Information: MS Code 37-3-2 establishes the Commission on Teacher and Administrator Education, Certification and Licensure and Development (the Commission) shall be composed of 15 qualified members. The purpose and duty of the Commission is to make recommendations to the State Board of Education regarding standards for the certification and licensure and continuing professional development of those who teach or perform tasks of an educational nature in the public schools of Mississippi. All appointments shall be made by the State Board of Education after consultation with the State Superintendent of Public Education. The State Board of Education, when making appointments, shall designate a chairman. The appointments are recommended in accordance with the internal operating policies of the Commission and Mississippi Code 37-3-2(2). Recommendations for Appointment Congressional District 1 Vacant Lay Person Congressional District 2 Dr. Debra Mays-Jacksqn Hinds Community College Congressional District 3 Dr. Jamilliah Longino Clinton Public Schools Recommendation: Approval Back-up material attached 1 TITLE 37. EDUCATION CHAPTER 3. STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Miss. Code Ann.§ 37-3-2 (2014) § 37-3-2. Certification of teachers and administrators (1) There is established within the State Department of Education the Commission on Teacher and Administrator Education, Certification and Licensure and Development. It shall be the purpose and duty of the commission to make recommendations to the State Board of Education regarding standards for the certification and licensure and continuing professional development of those who teach or perform tasks of an educational nature in the public schools of Mississippi. -

Msdhaggregate School Covid-19Report (By County & School)

MSDH AGGREGATE SCHOOL COVID-19 REPORT (BY COUNTY & SCHOOL) Week of Report: September 21 – September 25, 2020 As of 8:00 AM, September 29, 2020 N = 807 (schools reporting) in 77 counties Total NEW Total NEW COVID- COVID-19 Total NEW Total Teachers/Staff Total Students Total COVID-19 Total COVID-19 19 Positive Positive Outbreaks Quarantined due to Quarantined due to Positive Positive Students Total Outbreaks Teachers/Staff Students Week Week of Sept COVID-19 Exposure COVID-19 Exposure Teachers/Staff Since Since Start of Since Start of County/School Name Week of Sept 21-25 of Sept 21-25 21-25 Week of Sept 21-25 Week of Sept 21-25 Start of School School School Adams Cathedral Catholic School 0 0 0 0 5 1-5 1-5 0 Gilmer McLaurin Elementary 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Joseph L. Frazier Elementary 0 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 0 Morgantown Middle School 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Natchez Early College @Co-Lin 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Alcorn Alcorn Central Elementary 0 1-5 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Alcorn Central High 1-5 0 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Alcorn Central Middle 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Alcorn School District 1-5 0 0 0 0 1-5 0 0 Biggersville Elementary 1-5 0 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Biggersville High 0 1-5 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Corinth Elementary School 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 0 Corinth High School 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 14 0 Corinth Middle School 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 7 0 Kossuth Elementary 0 0 0 0 0 9 1-5 0 Kossuth High 1-5 0 0 0 0 1-5 10 0 Kossuth Middle 0 1-5 0 0 0 0 1-5 0 Amite Amite County Elementary School 0 0 0 0 0 1-5 1-5 1 Amite County High School 0 1-5 0 0 1 1-5 1-5 0 Attala Ethel High School 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Greenlee Elementary School -

School Desegregation in Mississippi

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION IN MISSISSIPPI James W. Loewen Tougaloo College August, 1973 Contents: I. Introduction 1 II. Race relations and school segregation before 1954 3 A. Education for whites 3 B. Education for blacks 6 C. Education for other groups 12 D. Schools and social structure on the eve of the 1954 decision 17 III. The 1954 decision and its aftermath 20 A. Immediate reaction: “Equalization” 20 B. Resistance 24 C. Longer-term reaction, 1954-63 27 D. Meredith and Ole Miss. 28 IV. Token desegregation, 1964-69 32 A. Freedom Summer and the 1964 Civil Rights Bill 32 B. The burden of token desegregation 34 C. “Freedom of Choice” 38 V. Higher education 46 VI. Massive desegregation 55 A. The Stennis Delay 55 B. Initial reaction 57 C. Cooperation 58 D. Black reaction to discrimination 63 E. Evasion 68 F. White withdrawal 69 G. Sex and race 79 VII. Conflict and accommodation 80 Endnotes 85 1 I. INTRODUCTION In January 1970, a principal spoke to student assembly, newly desegregated, in the southern part of the state of Mississippi. “You people are in a history-making situation,” said B.J. Oswalt to the now unitary high school in Columbia. “It can happen only once and you are part of it. Now, what are you going to do?” It was a question the nation was asking, as Mississippi schools went through the most massive social change ever requested of any educational system in the United States. The response in Marion County was surprisingly constructive: the white student body president said, “If everybody can just treat everybody else as a human being, it might just turn out all right – be a big surprise to everybody.” And the black student body president flashed the peace symbol, a unifying gesture to both races, and predicted, “We can become a lighthouse in Marion County.” Three years later, it is apparent that Mississippi has not yet become that lighthouse and that it still contains potential for vicious racism. -

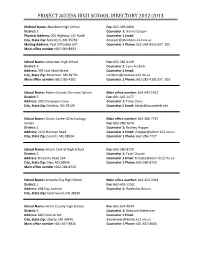

Project Access High School Directory 2012-2013

PROJECT ACCESS HIGH SCHOOL DIRECTORY 2012-2013 0School Name: Aberdeen High School Fax: 662-369-6004 District: 2 Counselor 1: Donna Cooper Physical Address: 205 Highway 145 North Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Aberdeen, MS 39730 [email protected] Mailing Address: Post OfficeBox 607 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-369-8933 EXT. 205 Main office number: 662-369-8933 School Name: Ackerman High School Fax: 662-285-4149 District: 4 Counselor 1: Lynn Scribner Address: 393 East Main Street Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Ackerman, MS 39735 [email protected] Main office number: 662-285-4101 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-285-4101 EXT. 103 School Name: Adams County Chrisitian School Main office number: 601-442-1422 District: 5 Fax: 601-442-1477 Address: 300 Chinquapin Lane Counselor 1: Tracy Davis City, State Zip: Natchez, MS 39120 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] School Name: Alcorn Career &Technology Main office number: 662-286-7727 Center Fax: 662-286-5674 District: 2 Counselor 1: Rodney Hopper Address: 2101 Norman Road Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Corinth, MS 38834 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-7727 School Name: Alcorn Central High School Fax: 662-286-8720 District: 2 Counselor 1: Tazel Choate Address: 8 County Road 254 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Glen, MS 38846 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-8720 Main office number: 662-286-8720 School Name: Amanda Elzy High School Main office number: 662-453-3394 District: 1 Fax: 662-453-1258 Address: 604 Elzy Avenue Counselor 1: