A Travelin' Girl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snehal Desai

East West Players and Japanese American Cultural & Community Center (JACCC) By Special Arrangement with Sing Out, Louise! Productions & ATA PRESENT BOOK BY Marc Acito, Jay Kuo, and Lorenzo Thione MUSIC AND LYRICS BY Jay Kuo STARRING George Takei Eymard Cabling, Cesar Cipriano, Janelle Dote, Jordan Goodsell, Ethan Le Phong, Sharline Liu, Natalie Holt MacDonald, Miyuki Miyagi, Glenn Shiroma, Chad Takeda, Elena Wang, Greg Watanabe, Scott Watanabe, and Grace Yoo. SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN PROPERTY DESIGN Se Hyun Halei Karyn Cricket S Adam Glenn Michael Oh Parker Lawrence Myers Flemming Baker FIGHT ALLEGIANCE ARATANI THEATRE PRODUCTION CHOREOGRAPHY PRODUCTION MANAGER PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Cesar Cipriano Andy Lowe Bobby DeLuca Morgan Zupanski COMPANY MANAGER GENERAL MANAGER ARATANI THEATRE GENERAL MANAGER Jade Cagalawan Nora DeVeau-Rosen Carol Onaga PRESS REPRESENTATIVE MARKETING GRAPHIC DESIGN Davidson & Jim Royce, Nishita Doshi Choy Publicity Anticipation Marketing EXECUTIVE PRODUCER MUSIC DIRECTOR ORCHESTRATIONS AND CHOREOGRAPHER ARRANGEMENTS Alison M. Marc Rumi Lynne Shankel De La Cruz Macalintal Oyama DIRECTED BY Snehal Desai The original Broadway production of Allegiance opened on November 8th, 2015 at the Longacre Theatre in NYC and was produced by Sing Out, Louise! Productions and ATA with Mark Mugiishi/Hawaii HUI, Hunter Arnold, Ken Davenport, Elliott Masie, Sandi Moran, Mabuhay Productions, Barbara Freitag/Eric & Marsi Gardiner, Valiant Ventures, Wendy Gillespie, David Hiatt Kraft, Norm & Diane Blumenthal, M. Bradley Calobrace, Karen Tanz, Gregory Rae/Mike Karns in association with Jas Grewal, Peter Landin, and Ron Polson. World Premiere at the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, California. Barry Edelstein, Artistic Director; Michael G. -

Stirring Chestnut Mare; Feb 16, 2002 Raise a Native, 61 Ch Mr

equineline.com Pedigree 10/05/16 12:38:03 EDT Stirring Chestnut Mare; Feb 16, 2002 Raise a Native, 61 ch Mr. Prospector, 70 b Gold Digger, 62 b Seeking the Gold, 85 b Buckpasser, 63 b Stirring Con Game, 74 dk b/ Broadway, 59 b Foaled in Kentucky Vice Regent, 67 ch Deputy Minister, 79 dk b/ Daijin, 92 b Mint Copy, 70 dk b/ Buckpasser, 63 b Passing Mood, 78 ch Cool Mood, 66 ch By SEEKING THE GOLD (1985). Stakes winner of $2,307,000, Super Derby [G1], etc. Among the leading sires in U.S., sire of 19 crops of racing age, 965 foals, 766 starters, 91 stakes winners, 4 champions, 547 winners of 1663 races and earning $95,002,319 USA, including Dubai Millennium (TF 140, Horse of the year in United Arab Emirates, $4,470,404 USA, Queen Elizabeth II S. [G1], etc.). Among the leading broodmare sires twice, sire of dams of 146 stakes winners, including champions Blame, Surfside, Up With the Birds, Take Charge Brandi, She Be Wild, Questing (GB), Catch the Thrill, Step In Time, La Tizona, Capo Grosso (CHI), Giulia, Zapper Pirate, Move Your Vision, and of Excellent Art (GB), Signs of Blessing. 1st dam DAIJIN, by Deputy Minister. 107. 4 wins at 3, $164,044, Selene S. [L] (WO, $66,900(CAN)), Star Shoot S. [L] (WO, $49,230(CAN)), 3rd Test S. [G1]. Sister to TOUCH GOLD. Dam of 9 foals, 6 to race, 6 winners-- KEE SEP YRLG 93, $150,000 (RNA) KEE NOV BRDG 92, $160,000, Buyer: N E T P SERENADING (f. -

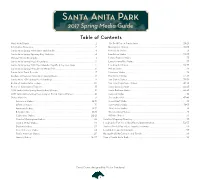

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

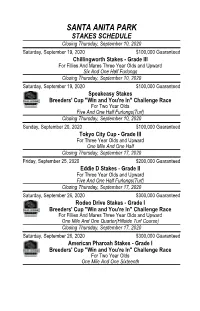

Sa Stakes Schedule Fall 2020

SANTA ANITA PARK STAKES SCHEDULE Closing Thursday, September 10, 2020 Saturday, September 19, 2020 $100,000 Guaranteed Chillingworth Stakes - Grade III For Fillies And Mares Three Year Olds and Upward Six And One Half Furlongs Closing Thursday, September 10, 2020 Saturday, September 19, 2020 $100,000 Guaranteed Speakeasy Stakes Breeders' Cup "Win and You're In" Challenge Race For Two Year Olds Five And One Half Furlongs(Turf) Closing Thursday, September 10, 2020 Sunday, September 20, 2020 $100,000 Guaranteed Tokyo City Cup - Grade III For Three Year Olds and Upward One Mile And One Half Closing Thursday, September 17, 2020 Friday, September 25, 2020 $200,000 Guaranteed Eddie D Stakes - Grade II For Three Year Olds and Upward Five And One Half Furlongs(Turf) Closing Thursday, September 17, 2020 Saturday, September 26, 2020 $300,000 Guaranteed Rodeo Drive Stakes - Grade I Breeders' Cup "Win and You're In" Challenge Race For Fillies And Mares Three Year Olds and Upward One Mile And One Quarter(Hillside Turf Course) Closing Thursday, September 17, 2020 Saturday, September 26, 2020 $300,000 Guaranteed American Pharoah Stakes - Grade I Breeders' Cup "Win and You're In" Challenge Race For Two Year Olds One Mile And One Sixteenth SANTA ANITA PARK STAKES SCHEDULE Closing Thursday, September 17, 2020 Saturday, September 26, 2020 $200,000 Guaranteed Chandelier Stakes - Grade II Breeders' Cup "Win and You're In" Challenge Race For Fillies Two Year Olds One Mile And One Sixteenth Closing Thursday, September 17, 2020 Saturday, September 26, 2020 $300,000 -

138904 08 Juvenilefillies.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $2,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE AND ONE-SIXTEENTH Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $2 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 22, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Artemis Agrotera Chestertown Farm Michael E. Hushion B.f.2 Roman Ruler - Indy Glory by A.P. Indy - Bred in New York by Chester Broman & Mary R. Broman Concave Reddam Racing, LLC Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Colonel John - Galadriel by Ascot Knight - Bred in Ontario by Windways Farm Limited Dancing House Godolphin Racing, LLC Kiaran P. -

2019 Spring Meet Media Guide

SANTA ANITA PARK 2019 SPRING MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 24-25 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 26-27 Santa Anita on Radio . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 27 Frank Mirahmadi Biography . 5 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 28 Jay Slender Biography . 5 Melair Stakes . 28 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 6 Monrovia Stakes . 29 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 6 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 7 Santa Barbara Stakes . 33-33 Santa Anita Spring 2018 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 7 Santa Margarita Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 8 Santa Maria Stakes . 36-37 Santa Anita Track Records . 9 Senorita Stake . 38-39 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 10 Shoemaker Mile . 40-41 Santa Anita 2018 Spring Meet Standings . 11 Singletary Stakes . 42 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 12 Snow Chief Stakes . 42 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 13 Summertime Oaks . 43-44 2018 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 14 Thor's Echo Stakes . 44 2018 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 14 Tokyo City Cup . 44-45 Stakes Histories . 15 Triple Bend Stakes . 46-47 Affirmed Stakes . 16 Wilshire Stakes . 48 American Stakes . 17-18 Satellite Wagering Directory . 49 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 18-19 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 50-51 Daytona Stakes . 20 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 52 Desert Stormer Stakes . 20 Local Hotels and Restaurants . 53 Dream of Summer Stakes . 20 Racing/Publicity Contacts and Credits . -

Sweden and Kollektivhus NU, [email protected] Kollektivhuskonf2010:Layout 1 10-09-08 00.50 Sida 5

Kollektivhuskonf2010:Layout 1 10-09-08 00.49 Sida 1 Living together – Cohousing Ideas and Realities Around the World Kollektivhuskonf2010:Layout 1 10-09-08 00.49 Sida 2 Kollektivhuskonf2010:Layout 1 10-09-08 00.49 Sida 3 Div of Urban and Regional Studies Living together – Cohousing Ideas and Realities Around the World Proceedings from the international collaborative housing conference in Stockholm 5–9 May 2010 DICK URBAN VESTBRO (editor) Report Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Royal Institute of Technology in collaboration with Kollektivhus NU Stockholm 2010 Kollektivhuskonf2010:Layout 1 10-09-08 00.50 Sida 4 Living together – Cohousing Ideas and Realities Around the World Proceedings from the international collaborative housing conference in Stockholm 5–9 May 2010 Report Division of Urban and Regional Studies in collaboration with Kollektivhus NU. Keywords: Cohousing, housing policy, communal living, eco-villages, demographic change The International Collaborative Housing Conference was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, Formas, and the housing companies shown below. Research grant Other sponsors Main sponsor Kollektivhuset Trädet, Göteborg © Division of Urban and Regional Studies, KTH, and Kollektivhus NU, 2010. Cover photo by Charles Durrett Graphic design: Ingrid Sillén, Migra Grafiska TRITA-SoM 2010-09 ISSN 1653-6126 ISRN KTH-SoM/R-10-09/SE ISBN: 978-91-7415-738-3 Printed by: Universitetsservice US AB, Stockholm 2010 Distribution: Division of Urban and Regional -

532-8623 Gardena Bowl Coffee Shop

2015 NISEI WEEK JAPANESE FESTIVAL ANNIVERSARY 7 5 TH ANNUAL JAPANESE FESTIVAL NISEI WEEK Pioneers, Community Service & Inspiration Award Honorees Event Schedules & Festival Map 2015 Queen Candidates Nisei Week Japanese Festival 1934 - 2015: “Let the Good Times Roll” 2014 Nisei Week Japanese Festival Queen Tori Angela Nishinaka-Leon CONTENTS NISEI WEEK FESTIVAL WELCOME FESTIVAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND INTRODUCTION 2015 Sponsors, Community Friends and Event Sponsors ... 42 Festival Greetings........................................... 10 2015 Nebuta Sponsors ..................................... 50 Grand Marshal: Roy Yamaguchi ............................. 16 2014 Queen’s Treasure Chest ............................... 67 Parade Marshal: Kenny Endo................................ 17 Supporters Ad Index....................................... 104 Pioneers: Richard Fukuhara, Toshio Handa, Kay Inose, 2015 Nisei Week Foundation Board, Madame Matsumae III, George Nagata, David Yanai ........ 24 Committees, and Volunteers............................... 105 Inspiration Award: Dick Sakahara, Michie Sujishi ............ 30 Community Service Awards: East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center, Evening Optimist Club of Gardena, Japanese Restaurant Association of America, Orange County Nikkei Coordinating Council, Pasadena Japanese Cultural Institute, San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center, Venice Japanese Community Center, West Los Angeles Japanese American Citizens League ........................ 36 CALENDAR OF EVENTS & FEATURES 2015 -

Living His Dream in Santa Anita

NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 1 PROFILE CRAIG LEWIS Living his dream in Santa Anita Craig Anthony Lewis is a racetrack lifer. And at 67, if genealogy and longevity mean anything, he still has a long way to go as a trainer. His father, Seymour, is 92. His mother, Norma, is 90. They still live together in Seal Beach, California. WORDS: ED GOLDEN PHOTOS: HORSEPHOTOS 14 TRAINERMAGAZINE.com ISSUE 34 NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 2 CRAIG LEWIS ISSUE 34 TRAINERMAGAZINE.com 15 NA TRAINER LEWIS ISSUE 34_Jerkins feature.qxd 23/10/2014 00:51 Page 3 PROFILE O “senior complexes” for them. No depressing assisted living warehouses. “My father still drives,” Craig says. “He’s sharper than I am.” NThat’s a mouthful from Lewis who, while not verbose when he speaks, is all meat and potatoes…as straight as Princess Kate’s teeth. Little wonder he knows his way around the track. He began his training career in 1978 and got his first taste of racing before it was time for his Bar Mitzvah. “I used to go to the track when I was a kid with my dad and that’s how I got started,” Lewis said. “I was fascinated by horse racing. I would go to Caliente on weekends with my brother. I was nine and he was 10. We were betting quarters with bookmakers and just kind of got swept up by it all.” More than half a century later, the broom still has bristles, thanks in small part to Lewis’ affiliation early on with legendary trainer Hirsch Jacobs, whose remarkable achievements have faded into racing’s Graded stakes winner Za Approval, Lee Vickers up, trots by Clement on the way to the track hinterlands over time. -

Sweden Ends Here? Social Movement Scenes and the Right to the City

SWEDEN ENDS HERE? SOCIAL MOVEMENT SCENES AND THE RIGHT TO THE CITY by Kimberly A. Creasap Bachelor of Arts, Bowling Green State University, 2001 Master of Liberal Studies, Eastern Michigan University, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kimberly A. Creasap It was defended on June 12, 2014 and approved by Annulla Linders, Associate Professor, Sociology, University of Cincinnati John Markoff, Distinguished University Professor, Sociology Suzanne Staggenborg, Professor, Sociology Dissertation Advisor: Kathleen Blee, Distinguished Professor, Sociology ii Copyright © by Kimberly A. Creasap 2014 iii SWEDEN ENDS HERE? SOCIAL MOVEMENT SCENES AND THE RIGHT TO THE CITY Kimberly A. Creasap, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This study examines social movement scenes—dynamic constellations of people and places— created by Swedish autonomous movements. Social movement scenes shape action, interpersonal dynamics among activists, and how activists see possibilities for social change. Autonomous movements reject representative democracy as a form of authority and, by extension, reject state institutions. This represents a radical departure from strict norms that characterize political and public life in Sweden in which political participation generally takes the form of party membership and/or activity with trade unions with strong ties to the state. Through ethnographic observation, in-depth interviews and analysis of artifacts such as newspapers, zines, flyers, and manifestos, I examine how and why Swedish autonomous social movements use “the Right to the City” as an organizing principle to create scenes as alternative forms of urban life in Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö. -

Transformation of Japanese American Community Through the Early Redevelopment Projects

Miya Suga(p237) 6/2 04.9.6 3:24 PM ページ 237 The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 15 (2004) Little Tokyo Reconsidered: Transformation of Japanese American Community through the Early Redevelopment Projects Miya SHICHINOHE SUGA* INTRODUCTION In the early 1960s, Little Tokyo, one of the oldest Japanese American communities in the mainland U.S., showed serious signs of decay. Many of the buildings in Little Tokyo were built at the turn of the century and devastated during the Second World War. In 1969, 32.6 percent of the total 138 buildings were categorized as “deficient/rehabilitation ques- tionable” and 43.5 percent as “structurally substandard.”1 Among 600 to 622 individuals and 41 families living there in 1969, those who were 62 or older composed more than 30 percent of the total population.2 Faced with the expansion of the City Hall nearby, this area was about to lose its function as a viable “ethnic community.” At this point, the people of Little Tokyo started to advocate its redevelopment and the Community Redevelopment Agency of the City of Los Angeles (CRA) decided to launch the Little Tokyo Redevelopment project in 1970.3 Thus far, transformation of Japanese American ethnicity in the domes- tic context has attracted wide scholarly attention. On the resilience of the Japanese American “ethnic community,” Fugita and O’Brien stress the significance of “a formal organizational base—a critical factor in the preservation of ethnic community life as individuals have moved from Copyright © 2004 Miya Shichinohe Suga. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. -

Japanese American Community Redevelopment in Postwar Los Angeles and South Bay

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2017 FESTIVALS, SPORT, AND FOOD: JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES AND SOUTH BAY Heather Kaori Garrett California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Food Studies Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather Kaori, "FESTIVALS, SPORT, AND FOOD: JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES AND SOUTH BAY" (2017). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 477. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/477 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FESTIVALS, SPORT, AND FOOD: JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES AND SOUTH BAY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Heather Kaori Garrett June 2017 FESTIVALS, SPORT, AND FOOD: JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES AND SOUTH BAY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Heather Kaori Garrett June 2017 Approved by: Cherstin M. Lyon, Committee Chair, History Arthur A. Hansen, Committee Member Ryan W. Keating, Committee Member © 2017 Heather Kaori Garrett ABSTRACT This study fills a critical gap in research on the immediate postwar history of Japanese American community culture in Los Angeles and South Bay.