Five Contemporary Autobiographical Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

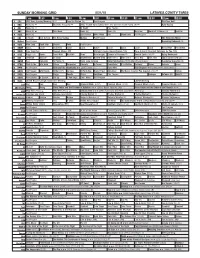

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

The Confessional Purgation of the Soul in the Poetry of Robert Lowell

Department of English The Flamekeeper: The Confessional Purgation of the Soul in the Poetry of Robert Lowell Ryan Jurison Degree of Bachelor, 15 points Literature Spring Term, 2020 Supervisor: Claudia Egerer Abstract This essay is a critical textual analysis of the poetry of Robert Lowell with focus on religious symbolism used in his work, and the Catholic theology which informed it. This results in a new, contrasting interpretation to the conventional view that he had abandoned his religious focus by mid-career, while accounting for his own assessment that he had not. Insights gained through this analysis, combined with those relating to Lowell’s personal history, reframe his confessional poetry while bolstering this claim. Through this study, poems selected from Lord Weary’s Castle, The Mills of the Kavanaughs, Life Studies and For the Union Dead are reinterpreted in order to explore the consequences of what Lowell could have intended with this stylistic modification, and discover the religiosity that he claimed was hidden. Lowell’s confessional poetry up until 1964 is examined and recast as the anguished wails of a Catholic soul in Purgatory. This fresh approach to one of America’s finest twentieth-century poets provides a novel foundation for the reinterpretation of the entirety of Lowell’s professional oeuvre. Keywords: Robert Lowell; American poetry; Catholic Theology; Religious Symbolism; Purgation; Purgatory; Land of Unlikeness; Lord Weary’s Castle; The Mills of the Kavanaughs; Life Studies; For the Union Dead Jurison 1 What soul is lost that does not think itself irrevocably so? When examining the poetry of Robert Lowell, and more specifically the equally lauded but outwardly contrasting work done from the beginning of his career to the middle, one cannot help but consider this question. -

The Mid-Twentieth-Century American Poetic Speaker in the Works of Robert Lowell, Frank O’Hara, and George Oppen

“THE OCCASION OF THESE RUSES”: THE MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN POETIC SPEAKER IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT LOWELL, FRANK O’HARA, AND GEORGE OPPEN A dissertation submitted by Matthew C. Nelson In partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2016 ADVISER: VIRGINIA JACKSON Abstract This dissertation argues for a new history of mid-twentieth-century American poetry shaped by the emergence of the figure of the poetic speaker as a default mode of reading. Now a central fiction of lyric reading, the figure of the poetic speaker developed gradually and unevenly over the course of the twentieth century. While the field of historical poetics draws attention to alternative, non-lyric modes of address, this dissertation examines how three poets writing in this period adapted the normative fiction of the poetic speaker in order to explore new modes of address. By choosing three mid-century poets who are rarely studied beside one another, this dissertation resists the aesthetic factionalism that structures most historical models of this period. My first chapter, “Robert Lowell’s Crisis of Reading: The Confessional Subject as the Culmination of the Romantic Tradition of Poetry,” examines the origins of M.L. Rosenthal’s phrase “confessional poetry” and analyzes how that the autobiographical effect of Robert Lowell’s poetry emerges from a strange, collage-like construction of multiple texts and non- autobiographical subjects. My second chapter reads Frank O’Hara’s poetry as a form of intentionally averted communication that treats the act of writing as a surrogate for the poet’s true object of desire. -

F18-Farrar-Straus-And-Giroux.Pdf

18F Macm Farrar, Straus and Giroux LEAD The Piranhas The Boy Bosses of Naples: A Novel by Roberto Saviano, translated by Antony Shugaar In Naples, there is a new kind of gang ruling the streets: the paranze, or the children's gangs, groups of teenage boys who divide their time between counting Facebook likes, playing Call of Duty on their PlayStations, and patrolling the streets armed with pistols and AK-47s, terrorizing local residents in order to mark out their Mafia bosses' territory. Roberto Saviano's The Piranhas tells the story of the rise of one such gang and its leader, Nicolas-known to his friends and enemies as the Maharajah. Nicolas's ambitions reach far beyond doing other men's bidding: he wants to be the one giving the orders, calling the shots, and ruling the city. But the violence he is accustomed to wielding and witnessing soon spirals beyond his control-with tragic consequences. "With the openhearted rashness that belongs to every true writer, Saviano returns to tell the story of the fierce and grieving heart of Naples." -Elena Farrar, Straus and Giroux Ferrante On Sale: Sep 1/18 6 x 9 • 368 pages 9780374230029 • $35.00 • CL - With dust jacket Author Bio Fiction / Literary Location: Roberto Saviano - Under police protection Notes Roberto Saviano was born in 1979 and studied philosophy at the University of Naples. Gomorrah, his first book, has won many awards, including the prestigious Viareggio Literary Award. Promotion National review attention Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator. He is the author of Coast to Coast -

The Piranhas the Boy Bosses of Naples: a Novel Roberto Saviano; Translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar

The Piranhas The Boy Bosses of Naples: A Novel Roberto Saviano; Translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar The saga of a city under the rule of a criminal network and the Neapolitan boys who create their own gang In Naples, there is a new kind of gang ruling the streets: the paranze, or the children’s gangs, groups of teenage boys who divide their time between counting Facebook likes, playing Call of Duty on their PlayStations, and FICTION patrolling the streets armed with pistols and AK-47s, terrorizing local residents in order to mark out their Mafia bosses’ territory. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/4/2018 9780374230029 | $27.00 / $35.00 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 368 pages Roberto Saviano’s The Piranhas tells the story of the rise of one such gang Carton Qty: 20 | 9 in H | 6 in W and its leader, Nicolas—known to his friends and enemies as the Maharajah. Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: The Wylie Agency Nicolas’s ambitions reach far beyond doing other men’s bidding: he wants to Audio: FSG be the one giving the orders, calling the shots, and ruling the city. But the violence he is accustomed to wielding and witnessing soon spirals beyond MARKETING his control—with tragic consequences. National review attention Roberto Saviano was born in 1979 and studied philosophy at the University of Print features and profiles Men’s interest media outreach Naples. Gomorrah, his first book, has won many awards, including the prestigious NPR and radio interviews Viareggio Literary Award. Original author essays Author appearances Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator. -

A Study .Of Robert Lowell's Life Studies

The Mode of Private Vision: A Study . of Robert Lowell's Life Studies Kim, Kil-Joong 1. Earlier Lowell: Lord Weary's Castle Life Studies (1959), coming after Land of Unlikeness (1944), Lord Weary's Castle(l946) , and Mills ofthe Kavanaughs(1951), marks a significant development or change in the poetry. of Robert Lowell. So before we discuss Life Studies, which is the main subject of this paper, it would be proper to attempt to define what was the characteristic concern of earlier Lowell. For this purpose, we will start, for the span of a few pages, by con centrating on Lord Weary's Castle. It seems to embody the greater and surer power of vision and language than the other two. The general impression of his earlier .poems was that of agonized violence and visionary energy directed against the darker aspects of the socio-historical milieu of modern times. Lowell had been a Roman Catholic convert since his graduation from Kenyon College, and its influence had visibly worked into his poetry. He made use of many Biblical themes and images, which added to the texture of his poetry. Lowell's poetry was dra matic and colloquial, ambiguous and paradoxical, but compared with the new poems, his figures and allusions were much denser and his tone more heightened. His rather rigorous iambic pentameters were questioning in grand Apocalyptic terms the contingencies of the moment and the meanings of the particular heritage in which he lived. On the one hand, the poet just survived the great world war with his memory of serving a six-month prison term as a conscientious objector. -

School of Unlikeness: the Creative Writing Workshop and American Poetry

School of Unlikeness: The Creative Writing Workshop and American Poetry Sarah Cohen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Brian Reed, Chair Jeanne Heuving Jessica Burstein Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract School of Unlikeness: American Poetry and the Creative Writing Workshop Sarah Cohen Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Brian Reed English This dissertation is a study of the creative writing workshop as a shaping institution of American poetry in the twentieth century. It takes as its starting point the observation that in the postwar period the rise of academic creative writing programs introduced profound material changes into the lives of American poets, as poetry became professionalized within the larger institution of the university. It goes on to argue that poets responded to these changes in ways that are directly legible in their work, producing a variety of poetic interrogations of the cultural and psychological effects of the reflexive professional self-fashioning that became, partially through the workshop, the condition of modern literary life. In other words, as poets became students and teachers, their classroom and career experiences occasioned new kinds of explorations of identity, performance, vocation, authority, and the cultural status of poets and poetry. The cluster of concerns linked to the evolving institution of "creative writing" shows stylistically diverse works to be united, and also resonates with and helps to clarify the major debates within the poetry world over the past decades between the camps of the "mainstream" and the "avant- garde" or, as Robert Lowell put it in 1959, "the cooked and the raw." My dissertation examines a variety of iterations of the relationship between workshop culture and poetic production through case studies of the poets Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Theodore Roethke, Richard Hugo, and Jorie Graham. -

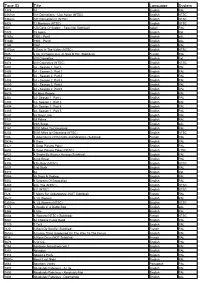

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Movieguide.Pdf

Movies Without Nudity A guide to nudity in 8,345 movies From www.movieswithoutnudity.com Red - Contains Nudity Movies I Own 300: Rise of an Empire (2014) A. I. - Artificial Intelligence (2001) A La Mala (aka Falling for Mala) (2014) A-X-L (2018) A.C.O.D. (2013) [Male rear nudity] Abandon (2002) The Abandoned (2007) Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) Abel's Field (2012) The Abolitionists (2016) Abominable (2019) Abominable (2020) About a Boy (2002) About Adam (2001) About Last Night (1986) About Last Night (2014) About Schmidt (2002) About Time (2013) Above and Beyond (2014) Above Suspicion (1995) Above the Rim (1994) Abraham (1994) [Full nudity of boys playing in water] The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) Absolute Power (1997) Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie (2016) An Acceptable Loss (2019) Accepted (2006) The Accountant (2016) Ace in the Hole (1951) Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995) [male rear nudity] Achilles' Love (2000) Across the Moon (1995) Across the Universe (2007) Action Jackson (1988) Action Point (2018) Acts of Violence (2018) Ad Astra (2019) Adam (2009) Adam at 6 A.M. (1970) Adam Had Four Sons (1941) Adam Sandler's Eight Crazy Nights (2002) Adam's Apples (2007) Adam's Rib (1949) Adaptation (2002) The Addams Family (2019) Addams Family Values (1993) Addicted (2014) Addicted to Love (1997) [Depends on who you ask, but dark shadows obscure any nudity.] The Adjuster (1991) The Adjustment Bureau (2011) The Admiral: Roaring Currents (aka Myeong-ryang) (2014) Admission (2013) Adrenaline Rush (2002) Adrift (2018) Adult Beginners (2015) Adult Life Skills (2019) [Drawings of penises] Adventures in Dinosaur City (1992) Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989) Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984) The Adventures of Elmo In Grouchland (1999) The Adventures of Huck Finn (1993) Adventures of Icabod and Mr. -

Performing the Erotic

Performing the erotic: (Re)presenting the body in popular culture by Dionne van Reenen Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the doctoral degree qualification Doctor of Philosophy with specialisation in English in the Department of English Faculty of Humanities at the University of the Free State Bloemfontein Submission date: 28 June 2019 Supervisor: Prof. S.A. Tate, Canada Research Chair Tier 1 in Feminism and Intersectionality, University of Alberta, Canada. Co-supervisors: Prof. H.J. Strauss, Chair: English Department, University of the Free State, South Africa; and Dr M.M. Mwaniki, Visiting Associate, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. I, Dionne van Reenen, declare that the research dissertation that I herewith submit for the doctoral degree qualification Doctor of Philosophy with specialisation in English (ENGD9100) at the University of the Free State is my independent work, and that I have not previously submitted it for a qualification at another institution of higher education. Signed: __________________ Date: 19 June 2019 iii Abstract In 1995, Mitchell suggested that spheres of public culture, and the academies that study them, are in the midst of a ‘pictorial turn’ which entails thinking about images in digital communication and mass multimedia as forms of life. In the study reported in this thesis, a critical semiotic analysis of mainstream, moving images that are designed, performed, mediated, and repeatable was conducted. The study focuses on the role of social constructs of gender, race, and class (along with size, age, and ability) in the ordering processes of society which are, in turn, sustained and reproduced by the (re)presentation of eroticised bodies in visual media in the twenty- first century. -

The Oxford Book of American Poetry

The Oxford Book of American Poetry Chosen and Edited by DAVID LEHMAN Associate Editor JOHN BREHM OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2006 Contents INTRODUCTION vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxiii ANNE BRADSTREET (C. 1612-1672) The Prologue 1 from Contemplations (When I behold the heavens as in their prime) 2 The Author to Her Book 3 Before the Birth of One of Her Children 3 To My Dear and Loving Husband 4 EDWARD TAYLOR (C. 1642-1729) Meditation III (Canticles 1.3: Thy Good Ointment) 5 Meditation VI (Canticles II 1:1 am... the lily of the valleys) 6 The Preface 6 Upon a Spider Catching a Fly 7 Huswifery 9 PHILIP FRENEAU (1752-1832) On the Emigration to America and Peopling the Western Country 10 The Wild Honey Suckle 11 The Indian Burying Ground 12 PHILLIS WHEATLEY (C. 1753-1784) On Being Brought from Africa to America 13 To The Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth 14 JOEL BARLOW (1754-1812) The Hasty-Pudding: Canto I 15 FRANCIS SCOTT KEY (1779-1843) Defence of Fort McHenry 18 xxvi CONTENTS CLEMENT MOORE (1779-1863) A Visit from St. Nicholas 20 FITZ-GREENE HALLECK (1790-1867) from Fanny 21 WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT (1794-1878) Thanatopsis 24 To a Waterfowl 26 Sonnet - To an American Painter Departing for Europe 26 RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1803-1882) A Letter 27 Concord Hymn 28 Each and All 28 Water 30 Blight 30 TheRhodora 31 The Snow-Storm 32 Hamatreya 3 3 Fable 34 Ode, Inscribed to W. H. Channing 35 Give All to Love 37 Bacchus 38 Brahma 40 Days 40 HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW (1807-1882) The Bridge 41 The Fire of Drift-Wood 42 The Jewish Cemetery at Newport 44 -

Robert Lowell and the Religious Sublime

HenryHart RobertLowell and the ReligiousSublime A J^JLs a student in his last year at St. Mark's, Robert Lowell published an interpre- tation of an allegorical drawing by his friend, Francis Parker, which reveals an early enchantment with religious sublimity. Although the piece in Vindex is characterized more by youthful idealism than hermeneutic skill, it is prophetic of the sort of poetry he would soon be writing. Lowell's explication begins with a grand moral pronounce- ment intended to separate the saints from the fools: 'The idea that we wish to make clear is that tremendous labor and great intelligence, if applied toward the advance- ment of evil or petty ends, are of no avail." He then proceeds to excoriate fourteen types of misguided intellectuals who surround the central figure of "St. Simon, the Stylite, a symbol of true knowledge." The fools are generally pedants and scientists, "men of authority who misuse their power" (129), and no doubt modelled with in- subordinate glee after Lowell's teachers. The young Lowell, full of sanctimonious ambitions, has his eye on the sublime "St. Simon [who] is elevated high above everyone else by comprehension of the true light. The book and the pen symbolize real intellectual attainment, while the plumb line signifies a quite natural feeling of superiority; but more important, his insecurity. From the sublime to the ridiculous is but a step." The sublime from Longinus and Burke to Kant and Harold Bloom has always been a measure of power and has always involved ranking that power according to a hierarchy of values.