Was Shylock Jewish-2-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Otherness' in Shakespeare's Othello and the Merchant Of

The Representation of ‘Otherness’ in Shakespeare’s Othello and The Merchant of Venice Othello and Shylock Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerda TISCHLER am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Werner Wolf Graz, 2013 Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Professor Werner Wolf, who has not only offered valuable guidance, assistance, and help in the composition of this thesis, but who has also been an inspiring and very encouraging mentor throughout the rest of my studies, supporting me in many ways. Additionally, I would like to thank my former teachers Waltraud Wagner and Liselotte Schedlbauer, who stirred up my enthusiasm for both the English language and literature. I also want to express my warmest and sincere thanks to my parents, who have always encouraged me in the actualisation of my dreams and who have been incredibly supportive in any respect throughout my entire life. Besides, I want to thank Christopher for showing so much sympathy and understanding, and for making me laugh wholeheartedly at least once a day. Lastly, I am indebted to my family, friends, and anyone without whom the completion of this thesis would not have been possible. Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 2 The ‘Other’ – Attempts at an Explanation ............................................................ -

The Merchant of Venice William Shakespeare Reviewed By: Kartikeya Krishna, 15 Star Teen Book Reviewer of Be the Star You Are! Charity

The Merchant of Venice William Shakespeare Reviewed by: Kartikeya Krishna, 15 Star Teen Book Reviewer of Be the Star You Are! Charity www.bethestaryouare.org Antonio is a young Venetian man and one of the most successful merchants of Venice, known for being kind and generous. His friend Bassanio wishes to travel to the city of Belmont to woo Portia, one of the most beautiful women in the world left with an amazing amount of money left after the death of her father. Bassanio asks Antonio if he can fund his trip to Belmont and Antonio, who is poor as of the moment as his ships are at sail, agrees as long as Bassanio can find a loaner, who turns out to be Shylock. Shylock hates Antonio because his racist attitude towards Jews, shown by Shylock being insulted and spat on by Antonio for being a Jew. Shylock decrees that if Antonio is unable to repay his loan before a specific date, he may take a pound of flesh from any part of Antonio’s body that he chooses. Antonio accepts the offer on account of being “surprised by Shylock’s generosity.” Bassanio leaves towards Belmont with his friend Gratanio. In Belmont, Portia’s father’s will is refraining her from marrying, stating that each of her suitors must choose correctly from one of three caskets -- gold, silver, and lead -- and if they choose correctly, they get Portia. If they are incorrect, they must leave and never marry. The first suitor chooses the gold casket because the casket says "Choose me and get what most men desire", which must be Portia, as what all men desire is Portia. -

The Merchant of Venice Theme: Exploring Shylock

Discovering Literature www.bl.uk/shakespeare Teachers’ Notes Curriculum subject: English Literature Key Stage: 4 and 5 Author / Text: William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice Theme: Exploring Shylock Rationale Shylock is one of Shakespeare’s most complex and troubling characters. He is marked from his very first appearance as an outsider in Venetian society, scorned and spat on by Christians and stripped of his wealth and religion. Nevertheless, he is also fuelled by vengeance. How are we to interpret Shylock as a character? Is he a stereotypical villain, or the victim of prejudice and racial hatred? These activities encourage students to explore the character of Shylock, setting him against the backdrop of myths and fears about Jews that existed in Shakespeare’s England. Students will examine some of the ways in which Shylock has been depicted on stage and will relate these different interpretations to changing cultural sensitivities. Content Literary and historical sources: Description of the Jewish Ghetto and the courtesans of Venice in Coryate's Crudities (1611) Doctor Lopez is accused of poisoning Elizabeth I (1627) The first illustrated works of Shakespeare edited by Nicholas Rowe (1709) Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (1633) Henry Irving as Shylock and Ellen Terry as Portia (1906–10) Photographs of Yiddish production of The Merchant of Venice (1946) Recommended reading (short articles): How were the Jews regarded in 16th-century England?: James Shapiro A Jewish reading of The Merchant of Venice: Aviva Dautch External links: -

![English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5082/english-202-in-italy-text-2-official-course-title-english-280-1-shakespeare-the-merchant-of-world-literature-i-dr-1175082.webp)

English 202 in Italy Text 2: [Official Course Title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, the Merchant of World Literature I Dr

Text 2: English 202 in Italy [Official course title: English 280-1] Shakespeare, The Merchant of World Literature I Venice Dr. Gavin Richardson EDITION: Any; the Folger Shakespeare is recommended. READING JOURNAL: In a separate document, write 3-5 thoughtful sentences in response to each of these reading journal prompts: 1. Act 1 scene 3 features the crucial loan scene. At this point, do you think Shylock is serious about the pound of flesh he demands as collateral for Antonio’s loan for Bassanio? Why or why not? 2. In 2.3. Jessica leaves her (Jewish) father for her (Christian) husband. Does her desertion create sympathy for Shylock? Or do we cheer her action? Is her “conversion” an uplifting one? 3. Shylock’s speech in 3.1.58–73 may be the most famous of the entire play. After reading this speech, review Ann Barton’s comments on the performing of Shylock and write a paragraph on what you think Shylock means to Shakespeare: “Shylock is a closely observed human being, not a bogeyman to frighten children in the nursery. In the theatre, the part has always attracted actors, and it has been played in a variety of ways. Shylock has sometimes been presented as the devil incarnate, sometimes as a comic villain gabbling absurdly about ducats and daughters. He has also been sentimentalized as a wronged and suffering father nobler by far than the people who triumph over him. Roughly the same range of interpretation can be found in criticism on the play. Shakespeare’s text suggests a truth more complex than any of these extremes.” 4. -

Revisiting Shakespeare's Problem Plays: the Merchant of Venice

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 v For Hayriye Gülden, Sertaç Süleyman and Talat Serhat ÇAĞLAYAN and Emre MAZANOĞLU vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my endless gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. A. Deniz BOZER for her great support, everlasting patience and invaluable guidance. Through her extensive knowledge and experience, she has been a model for me. She has been a source of inspiration for my future academic career and made it possible for me to recognise the things that I can achieve. I am extremely grateful to Prof. Dr. Himmet UMUNÇ, Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, Asst. Prof. Dr. Şebnem KAYA and Asst. Prof. Dr. Evrim DOĞAN ADANUR for their scholarly support and invaluable suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Suganthi John and Michelle Devereux who supported me by their constant motivation at CARE at the University of Birmingham. They were the two angels whom I feel myself very lucky to meet and work with. I also would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Dobson, the director of the Shakespeare Institute and all the members of the Institute who opened up new academic horizons to me. I would like to thank Dr. -

A Žižekian Reading of the Jewish Question in the Merchant of Venice

CLEaR , 2016, 3(2), ISSN 2453 - 7128 DOI: 10.1515/clear - 2016 - 0011 “Which is the Merchant and which is the Jew?” a Žižekian Reading of the Jewish Question in The Merchant of Venice Shih - pei Kuo National Chengchi University , Taiwan [email protected] Abstract This essay borrows Zižek ’ s interpretation of racism which combines the Marxist and psychoanalytic perspectives to read Shakespeare ’ s The Merchant of Venice . I argue that Shylock , the Jewish usurer , embodies both the structural contradiction of capitalism and the social contradiction which characterizes the Venetian setting torn by capitalism and Christianity. As Shylock exposes these contradictions which the Christian Venetians refuse to confront, h e is destined to be a scapegoat. From the Marxist point of view, the survival of capitalism relies on incessant production, which also means incessant investment of capital. Therefore, an active financial system is requisite to sustain the prosperity of ca pitalism. Paradoxically, this necessary condition of capitalism which facilitates the maximum use of cash is also its inherent vulnerability: once the circulation of cash is disrupted, it can lead to the crisis of the overall domino - effect collapse. The us ury represented by Shylock indeed reflects such inherent contradiction of capitalism. Also, usury, which excludes any human factor and only engages the direct monetary exchange, also contradicts the Christian orthodox belief of generosity and unrequited de votion. These central Christian values a re certainly questioned as Bassa nio ’ s courtship of Portia, based on his disguised wealth, is indistinguishable from a profitable enterprise. From the psychoanalytic point of view, Shylock ’ s fas cination with money and revenge also mirrors the Christians ’ clandestine longing for these two forbidden enjoyments. -

92. Judaism and Jews B R E T T D

book identifi es Easter Term as starting the eighteenth day such an overt liturgical allusion as Shakespeare provides aft er Easter and ending the Monday aft er the Ascension. in the title Twelft h Night was certainly not a reference to Trinity Term began the Friday aft er Trinity Sunday and the religious nature of the feast, or even to a performance ended June 28. Michaelmas Term began October 9 or 10 date, but to the atmosphere of frivolous chaos that had and ended November 28 or 29. Hillary Term began January developed over the years. It is far more likely that the 23 or 24 and ended February 12 or 13. During term time, timing of these performances was based on ecclesiasti- the court did not sit on Sundays or on the feasts of the cal rules regarding secular entertainment during certain Ascension, John the Baptist, All Saints, or the Purifi cation seasons of the year. Th e penitential seasons of Advent of Mary. and Lent, for example, were inappropriate for theatrical amusements. Dramatic performances S o u r c e c i t e d and the liturgical year G a r d i n e r , S a m u e l . Th e Cognizance of a True Christian, or the Dramatic performances were oft en scheduled to coin- outward markes whereby he may be the better knowne , etc. cide with certain church seasons or feasts. Th is practice London : Th omas Creede , 1597 . was not new to the English Renaissance, however. Th e medieval mystery plays serve as a prime example of the F u r t h e r r e a d i n g long-standing connection between theater, religion, and B r y a n t , J a m e s C . -

Trial by Jewry: the Jewish Figure As Subversive Critic in the Plays of The

I University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. "Trial By Jewry*: The Jewish Figure as Subversive Critic in the Plays of the Public Theatre, 1580-1600 by Lloyd Edward Kermode A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Birmingham in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Philosophy The Shakespeare Institute. August 1992 SYNOPSIS This thesis sets out to analyse the role of the Jewish figure on the late Elizabethan public stage. To do this, an historical approach is used. The first chapter charts generally the movements of the Jews on the Continent in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-centuries, showing how some Jews were to find their way to England, and where those Jews lived; but also painting a picture of the Jews' situation in various key European locations, a picture from which many images found their way onto the English stage. The second chapter analyses the place of the public theatre in the suburbs around London, and surveys the English arena into which the Jews were received. Chapters three to seven follow the estimated early performances of the plays involving Jewish or 'Jew-ish 1 figures, and analyse the social, cultural, religious and political significance of the interest in a race of people officially absent from the country since 1290. -

The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Summer 2015 The aB ttle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare Erin K. Miller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Erin K., "The aB ttle of Good nda Evil in Shakespeare" (2015). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 70. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/70 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Battle of Good and Evil in Shakespeare A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Erin Miller July 2015 Mentor: Dr. Patricia Lancaster Reader: Dr. Jennifer Cavenaugh Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Introduction Drama through the ages—from the Greeks’ Oedipus Rex to the morality plays of the Middle Ages —centers on an exploration of the human condition. In antiquity, religious celebrations to honor the gods and appeal for their favor gradually give birth to Greek theater, and these early plays, most of which are tragedies, focus on man’s suffering. What starts as the impact of fate on the life of man becomes, by the Middle Ages, a religious spectacle centered on evil’s impact on man. The Church of the Middle Ages frames the battle as a conflict of vice and virtue through stories in the life of Christ. -

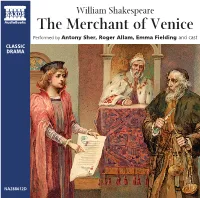

The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and Cast CLASSIC DRAMA

William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA288612D 1 Act 1 Scene 1: In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: 9:55 2 Act 1 Scene 2: By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary… 7:20 3 Act 1 Scene 3: Three thousand ducats; well. 6:08 4 Signior Antonio, many a time and oft… 4:06 5 Act 2 Scene 1: Mislike me not for my complexion… 2:26 6 Act 2 Scene 2: Certainly my conscience… 4:21 7 Nay, indeed, if you had your eyes, you might fail of… 4:19 8 Father, in. I cannot get a service, no; 2:49 9 Act 2 Scene 3: Launcelot I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so: 1:15 10 Act 2 Scene 4: Nay, we will slink away in supper-time, 1:50 11 Act 2 Scene 5: Well Launcelot, thou shalt see, 3:16 12 Act 2 Scene 6: This is the pent-house under which Lorenzo… 1:32 13 Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains. 1:49 14 Act 2 Scene 7: Go draw aside the curtains and discover… 5:04 15 O hell! what have we here? 1:23 16 Act 2 Scene 8: Why, man, I saw Bassanio under sail: 2:27 17 Act 2 Scene 9: Quick, quick, I pray thee; draw the curtain straight: 6:48 2 18 Act 3 Scene 1: Now, what news on the Rialto Salerino? 2:13 19 To bait fish withal: 5:17 20 Act 3 Scene 2: I pray you, tarry: pause a day or two… 4:39 21 Tell me where is fancy bred… 6:52 22 You see me, Lord Bassanio, where I stand… 9:56 23 Act 3 Scene 3: Gaoler, look to him: tell not of Mercy… 2:05 24 Act 3 Scene 4: Portia, although I speak it in your presence… 3:56 25 Act 3 Scene 5: Yes, truly; for, look you the sins of the father… 4:28 26 Act 4 Scene 1: What, is Antonio here? 4:42 27 What judgment shall I dread, doing. -

The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare

The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare In A Nutshell The Merchant of Venice is a comedy written by William Shakespeare around 1597. It tells the story of two Venetian merchants who loathe each other, Antonio and Shylock, and their business deal undertaken on behalf of Antonio's good friend, Bassanio. One of the merchants, Shylock, is a Jew living in the heavily Christian Venetian society; and religious prejudice and tension infuse the entire play. For Shakespeare, writing to an English audience about a Jewish moneylender might have seemed unusual, as Jews had been banished from England in 1290 under The Edict of Expulsion. How was Shakespeare to explain the Jewish presence to Elizabethan audiences, who had little exposure to Jewish culture and religion? Shakespeare's literary rival, Christopher Marlowe had actually just written a play called The Jew of Malta in 1589. That play’s title character was a Jew named Barabas, and as a greedy, cunning, and murderous stereotype, he fit the bill of "stock" Jewish characters that Elizabethan theatergoers of the time loved to hate. Of course, since there were no actual Jews publicly living in England, the worst kinds of stereotypes and legends about the entire group could prevail unchecked. The stories got more and more fantastic, including everything from sacrificing kidnapped Christian children on Easter to killing full-grown Christians for their blood to be used in Passover rituals. Christopher Marlowe’s play, and his inexplicably evil Jewish protagonist, sparked English thinking about the long-absent English Jews. Visit Shmoop for full coverage of The Merchant of Venice Shmoop: study guides and teaching resources for literature, US history, and poetry Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 This document may be modified and republished for noncommercial use only. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory