Joe Frazier's Gym” - Is a Good Clue That This Place Is No Candidate for the Wrecker's Ball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Sports Law Brochure

ahead ofthegame Sports Law SECTION ROW SEAT 86 H 1 625985297547 Hitting home runs Building Synergies with Renowned Brands for a legendary brand Herrick created the framework Rebuilding the House that Ruth Built and template agreements Game Day Our Sports Law Group rallied Herrick’s that govern advertising, real estate, corporate and tax lawyers promotion and product to structure five separate bond financ- placement rights for stadium Herrick’s Sports Law Group began advising the New York Yankees in the early ings, totaling in excess of $1.5 billion, sponsors. We have also which laid the financial foundation helped the Yankees extend Smooth Ride for Season Ticket Licensees 1990s, right as they began their march into a new era of excellence, both for the new Yankee Stadium. Our their brand by forming Playing musical chairs with tens of thousands cross-disciplinary team also advised on innovative joint ventures for of sports fans is tricky. We co-designed on and off the field. For more than two decades, our lawyers have helped the a number of complex matters related to a wide range of products, with the Yankees a season ticket license world’s most iconic professional sports franchise form innovative joint ventures, the new Yankee Stadium’s lease including the best-selling program for obtaining the rights to seats and construction. New York Yankees cologne. at the new Yankee Stadium. unleash new revenue streams, finance and build the new Yankee Stadium, and maximize the value of the team’s content – all of which have contributed Sparking the Regional to a global brand that’s unparalleled in the history of professional sports. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Weekend Derailments Kill Nineteen

Weekend derailments kill nineteen early Sunday sev- side the tracks, but most were including the man who has been in (COMPILED FROM AP/UPI REPORTS) -- At ty of Youngstown by the searing charge of probing Friday's derail- least 19 persons have died as the re- eral cars of an Atlanta and St. quickly overcome greenish-yellow cloud. ment in Waverly, Tenn. sult of freight train derailments Andrews Bay freight train jumped Some of the victims lived in Near Cades, Tenn. 25 cars of an along southern tracks over the week- the tracks, sending clouds of from a near-by homes. Illinois Central Gulf train derail- end. chlorine gas into the air Bay County Sheriff's Deputy Tom ed Sunday forcing evacuation of 250 The death toll in Friday's pro- ruptured tank car. died shortly after Loftin said he was driving to the residents when caustic lye leaked pane tank car explosion in Waverly, Seven persons and an eighth victim scene before he knew what had hap- from a tanker and filled the air Tenn. now stands at 11. the accident, was spotted near the scene by a pened. with a nauseating odor. in the after- The derailment occurred about 60 Leaking chlorine gas from a de- helicopter pilot later What he found were miles west of Waverly where 11 per- railed car near Youngstown, Fla. people stum- were hospital- bling along the highway, vomiting sons died after the explosion of early Sunday took at least eight Forty-one persons were evacuated from and screaming for help. a derailed propane tank car Friday. -

Who Wears a Veil?

the Middle East What factors determine the changing roles of women in the Middle East and Islamic societies? Lesson 1: Who Wears a Veil? Which women are Muslim? Hindu? Christian? Jewish? Can you tell by looking at them? Check the key on the following pages to find out. 12345 678910 © 2002 WGBH Educational Foundation www.pbs.org/globalconnections the Middle East What factors determine the changing roles of women in the Middle East and Islamic societies? Lesson 1: Who Wears a Veil? (cont’d.) 1. Mother Teresa – Christian er of many causes, among them health care for women Catholic Nun and Humanitarian and children, education, environmental protection, Mother Teresa was born Gonxhe Agnes Bojaxhiu in preservation of culture, public architecture, and the Skopje, in present-day Macedonia (then capital of the banning of land mines. She is Muslim. Depending on Ottoman province of Kosovo). At 18, she joined the the circumstances, Queen Noor may or may not cover Irish Catholic order of the Sisters of Loreto. After a her hair loosely. brief period in Ireland, she was sent to teach just out- side of Calcutta, India, at St. Mary's High School, of 3. Dr. Amina McCloud – Muslim which she later became principal. She learned local Scholar of Islam in America languages, including Hindi and Bengali, and in 1946 Amina Beverly McCloud converted to Islam in 1966. A dedicated herself to serving the poorest of the poor. professor of Islamic Studies at DePaul University in She founded her own order, the Missionaries of Charity, Chicago, she studies Islam and Muslim life in the in 1950. -

Singleton-Prather, Anita and Charles Singleton

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Video Collection Gullah Digital Archive 7-23-2012 Singleton-Prather, Anita and Charles Singleton Anita Singleton Prather Charles Dennis Singleton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/gullah_video Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Prather, Anita Singleton and Singleton, Charles Dennis, "Singleton-Prather, Anita and Charles Singleton" (2012). Video Collection. Paper 123. https://digital.kenyon.edu/gullah_video/123 This Video is brought to you for free and open access by the Gullah Digital Archive at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Video Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gullah Digital Archive Anita Singleton Prather, Charles Dennis Singleton July 23, 2012 St. Helena Island AP: July 23, 2012, Anita Joy Singleton Prather. CS: And my name is Charles Dennis Singleton, and I am Anita Prather’s brother. Unknown: [Off Camera] Can you tell us how long you’ve lived here in the Beaufort area, please? AP: 55 years for me. 57 for [points to Charles]... CD: 57 on me, I’m 57 years old, so. But I didn’t always live here. After I finished high school my heart had a desire to be a boxer. And so, I moved to Atlanta, Georgia, and that’s where I started making that happen, being a boxer in Atlanta, Georgia. And from there, I was in Atlanta from ‘73 to ‘75. While I was there I went towhat’s the name of that school? DeVry Tech? AP: Mhm. -

The Epic 1975 Boxing Match Between Muhammad Ali and Smokin' Joe

D o c u men t : 1 00 8 CC MUHAMMAD ALI - RVUSJ The epic 1975 boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Thriller in Manila – was -1- 0 famously brutal both inside and outside the ring, as a neW 911 documentary shows. Neither man truly recovered, and nor 0 did their friendship. At 64, Frazier shows no signs of forgetting 8- A – but can he ever forgive? 00 8 WORDS ADAM HIGGINBOTHAM PORTRAIT STEFAN RUIZ C - XX COLD AND DARK,THE BIG BUILDING ON of the world, like that of Ali – born Cassius Clay .pdf North Broad Street in Philadelphia is closed now, the in Kentucky – began in the segregated heartland battered blue canvas ring inside empty and unused of the Deep South. Born in 1944, Frazier grew ; for the first time in more than 40 years. On the up on 10 acres of unyielding farmland in rural Pa outside, the boxing glove motifs and the black letters South Carolina, the 11th of 12 children raised in ge that spell out the words ‘Joe Frazier’s Gym’ in cast a six-room house with a tin roof and no running : concrete are partly covered by a ‘For Sale’ banner. water.As a boy, he played dice and cards and taught 1 ‘It’s shut down,’ Frazier tells me,‘and I’m going himself to box, dreaming of being the next Joe ; T to sell it.The highest bidder’s got it.’The gym is Louis. In 1961, at 17, he moved to Philadelphia. r where Frazier trained before becoming World Frazier was taken in by an aunt, and talked im Heavyweight Champion in 1970; later, it would also his way into a job at Cross Brothers, a kosher s be his home: for 23 years he lived alone, upstairs, in slaughterhouse.There, he worked on the killing i z a three-storey loft apartment. -

BCN 205 Woodland Park No.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 September-October 2011

BCN 205 Woodland Park no.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 september-october 2011 FIRST CLASS MAIL Olde Prints BCN on the web at www.boxingcollectors.com The number on your label is the last issue of your subscription PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.HEAVYWEIGHTCOLLECTIBLES.COM FOR RARE, HARD-TO-FIND BOXING ITEMS SUCH AS, POSTERS, AUTOGRAPHS, VINTAGE PHOTOS, MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS, ETC. WE ARE ALWAYS LOOKING TO PURCHASE UNIQUE ITEMS. PLEASE CONTACT LOU MANFRA AT 718-979-9556 OR EMAIL US AT [email protected] 16 1 JO SPORTS, INC. BOXING SALE Les Wolff, LLC 20 Muhammad Ali Complete Sports Illustrated 35th Anniver- VISIT OUR WEBSITE: sary from 1989 autographed on the cover Muhammad Ali www.josportsinc.com Memorabilia and Cassius Clay underneath. Recent autographs. Beautiful Thousands Of Boxing Items For Sale! autographs. $500 BOXING ITEMS FOR SALE: 21 Muhammad Ali/Ken Norton 9/28/76 MSG Full Unused 1. MUHAMMAD ALI EXHIBITION PROGRAM: 1 Jack Johnson 8”x10” BxW photo autographed while Cham- Ticket to there Fight autographed $750 8/24/1972, Baltimore, VG-EX, RARE-Not Seen Be- pion Rare Boxing pose with PSA and JSA plus LWA letters. 22 Muhammad Ali vs. Lyle Alzado fi ght program for there exhi- fore.$800.00 True one of a kind and only the second one I have ever had in bition fi ght $150 2. ALI-LISTON II PRESS KIT: 5/25/1965, Championship boxing pose. $7,500 23 Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton 9/28/76 Yankee Stadium Rematch, EX.$350.00 2 Jack Johnson 3x5 paper autographed in pencil yours truly program $125 3. -

Boxing Edition

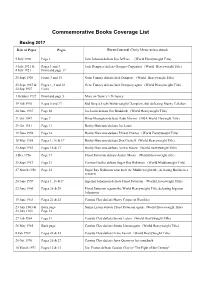

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

In This Corner

Welcome UPCOMING Dear Friends, On behalf of my colleagues, Jerry Patch and Darko Tresnjak, and all of our staff SEA OF and artists, I welcome you to The Old TRANQUILITY Globe for this set of new plays in the Jan 12 - Feb 10, 2008 Cassius Carter Centre Stage and the Old Globe Theatre Old Globe Theatre. OOO Our Co-Artistic Director, Jerry Patch, THE has been closely connected with the development of both In This Corner , an Old Globe- AMERICAN PLAN commissioned script, and Sea of Tranquility , a recent work by our Playwright-in-Residence Feb 23 - Mar 30, 2008 Howard Korder, and we couldn’t be more proud of what you will be seeing. Both plays set Cassius Carter Centre Stage the stage for an exciting 2008, filled with new work, familiar works produced with new insight, and a grand new musical ( Dancing in the Dark ) based on a classic MGM musical OOO from the golden age of Hollywood. DANCING Our team plans to continue to pursue artistic excellence at the level expected of this IN THE DARK institution and build upon the legacy of Jack O’Brien and Craig Noel. I’ve had the joy and (Based on the classic honor of leading the Globe since 2002, and I believe we have been successful in our MGM musical “The Band Wagon”) attempt to broaden what we do, keep the level of work at the highest of standards, and make Mar 4 - April 13, 2008 certain that our finances are healthy enough to support our artistic ambitions. With our Old Globe Theatre Board, we have implemented a $75 million campaign that will not only revitalize our campus but will also provide critical funding for the long-term stability of the Globe for OOO future generations. -

Muhammad Ali Dies at 74 – Reactions

Muhammad Ali Dies At 74 – Reactions Former world heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali died on Friday, aged 74. Following are some of the immediate reactions to the news: REV. AL SHARPTON, NEW YORK-BASED CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER, ON TWITTER”Ali, he was and always will be the greatest. A true champion in and out of the ring.” REV. JESSE JACKSON SR., CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER, ON TWITTER”Let us pray for @MuhammadAli; good for America, world boxing champion, social transformer & anti-war hero. #TheGreatest.” ROY JONES JR., FORMER BOXING CHAMPION, ON TWITTER “My heart is deeply saddened yet both appreciative and relieved that the greatest is now resting in the greatest place.” GEORGE FOREMAN, ALI’S OPPONENT IN THE “RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE” “Muhammad Ali was one of the greatest human beings I have ever met. No doubt he was one of the best people to have lived in this day and age. To put him as a boxer is an injustice.” BERNICE KING, DAUGHTER OF CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER MARTIN LUTHER JR. “You were a champion in so many ways. You ‘fought’ well. Rest well.” FLOYD MAYWEATHER JR, FIVE DIVISION WORLD CHAMPION “There will never be another Muhammad Ali. The black community all around the world, black people all around the world, needed him. He was the voice for us. He’s the voice for me to be where I’m at today.” DON KING, BOXING PROMOTER “It’s a sad day for life, man. I loved Muhammad Ali, he was my friend. Ali will never die. Like Martin Luther King his spirit will live on, he stood for the world.” MANNY PACQUIAO, FILIPPINO BOXER AND POLITICIAN “We lost a giant today. -

Boxers of the 1940S in This Program, We Will Explore the Charismatic World of Boxing in the 1940S

Men’s Programs – Discussion Boxers of the 1940s In this program, we will explore the charismatic world of boxing in the 1940s. Read about the top fighters of the era, their rivalries, and key bouts, and discuss the history and cultural significance of the sport. Preparation & How-To’s • Print photos of boxers of the 1940s for participants to view or display them on a TV screen. • Print a large-print copy of this discussion activity for participants to follow along with and take with them for further study. • Read the article aloud and encourage participants to ask questions. • Use Discussion Starters to encourage conversation about this topic. • Read the Boxing Trivia Q & A and solicit answers from participants. Boxers of the 1940s Introduction The 1940s were a unique heyday for the sport of boxing, with some iconic boxing greats, momentous bouts, charismatic rivalries, and the introduction of televised matches. There was also a slowdown in boxing during this time due to the effects of World War II. History Humans have fought each other with their fists since the dawn of time, and boxing as a sport has been around nearly as long. Boxing, where two people participate in hand-to-hand combat for sport, began at least several thousand years ago in the ancient Near East. A relief from Sumeria (present-day Iraq) from the third millennium BC shows two facing figures with fists striking each other’s jaws. This is the earliest known depiction of boxing. Similar reliefs and paintings have also been found from the third and second millennium onward elsewhere in the ancient Middle East and Egypt. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Ballgame Local teams go head to head in CAPE CORAL Bud Roth tourney DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Mostly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 89 Friday, April 17, 2009 50 cents Cape man guilty on all counts in ’05 shooting death “I’m very pleased with the verdict. This is a tough case. Jurors deliberate for nearly 4 hours It was very emotional for the jurors, but I think it was the right decision given the evidence and the facts of the By CONNOR HOLMES tery with a deadly weapon. in the arm by co-defendant Anibal case.” [email protected] Gaphoor has been convicted as Morales; Jose Reyes-Garcia, who Dave Gaphoor embraced his a principle in the 2005 shooting was shot in the arm by Morales; — Assistant State Attorney Andrew Marcus mother, removed his coat and let death of Jose Gomez, 25, which and Salatiel Vasquez, who was the bailiff take his fingerprints after occurred during an armed robbery beaten with a tire iron. At the tail end of a three-day made the right decision. a 12-person Lee County jury found in which Gaphoor took part. The jury returned from approxi- trial and years of preparation by “I’m very pleased with the ver- him guilty Thursday of first-degree Several others were injured, mately three hours and 45 minutes state and defense attorneys, dict,” he said Thursday. “This is a felony murder, two counts of including Rigoberto Vasquez, who of deliberations at 8 p.m.