Implementing an Operational Risk Management Framework at BNP Paribas Lisbon: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation Patrice MENARD October 2008

BNP Paribas Patrice MENARD Investor Relations Officer Switzerland / Netherlands October 2008 1 Record earnings despite the crisis Corporate governance 2 A European Leader with a Worldwide Footprint Europe (excl. France/Italy) 46,000 employees Italy United States 20,000 employees 15,000 employees Asia 9,800 employees Rest of the world 15,200 employees France incl. overseas depts./territories 64,000 employees Present in over 85 countries 170,000 employees* worldwide of which 130,000 in Europe (76% of the total) *Persons employed 3 A European Leader with a Global Franchise Breakdown of 1H08 revenues by core business Corporate & Others Retail Investment Banking 15% Banking in France 22% 20% North America 11% BNL bc France 9% 47% Other Asset Western Management International Europe & Services Retail 13% Italy 19% 14% Services 30% WesternWestern Europe Europe RetailRetail banking banking 74%74% 59%59% 4 Good Revenue Momentum Revenues -24.5% +8.0% +3.0% +2.9% 2,452 2,108 2,153 1,993 1,520 1,852 2Q08 1,357 1,396 1,470 1,514 +6.5% 1,263 1,311 1Q08 2Q07 643 680 685 % 2Q08/2Q07 In €m RBF BNL bc IRS AMS CIB Retail Banking eur 6 25% F 2/3 25% F 2/3 25% F 2/3 BNL BNL BNL bc bc bc AMS AMS AMS 19% IRS 19% IRS 19% IRS 57% 18% 25% 5 Effective Cost Control Maintains Operating Efficiency Operating Expenses Cost/income ratio 11.4% 67.5% 10.3% 7.0% 64.0% 4.9% 62.2% 62.7% 0.7% 59.7% 0% 58.9% Change Q/Q-4 -2.8% 1Q07 2Q07 3Q07 4Q07 1Q08 2Q08 1Q07 2Q07 3Q07 4Q07 1Q08 2Q08 FlexibleFlexible cost cost structure structure in in the the business business lines lines -

BNP-PARIBAS-ZAO-2011-ENG.Pdf

CONTENTS: I. INTRODUCTION 05 The message from the Supervisory Board 06 About the BNP Paribas Group 10 Management II. STRATEGY AND RESULTS 2011 Macroeconomics and the Russian banking industry in 2011 15 16 Financial results 2011 27 Corporate investment bank 31 Consumer fi nancing 33 Risk Management 35 Human Resources Management 36 Corporate Code of Conduct III. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 38 State Registration Information 38 Participation in Associations 40 Contact Information I. INTRODUCTION BNP PARIBAS ZAO 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 THE MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERVISORY BOARD am pleased to present the BNP market conditions. PARIBAS ZAO annual report for In 2011, we started up a new trading 2011. and marketing activity in commodity de- The year was dominated by rivatives to meet the increasing demand global uncertainty and extremely in the Russian market. We expect this I complex fi nancial conditions product line to be an important contrib- combined with new regulatory utor to our 2012 revenues. challenges. In 2011, our work was fo- On a wider scale, 2011 was a year of cused on adapting ourselves to the new signifi cant changes to the business strat- operating environment. Now, our compa- egies for BNP Paribas Group in Russia. ny has adjusted to the new environment Corporate Investment Banking and and we have already made signifi cant Personal Finance activities were pro- progress in realignment. Thanks to the vided by the same legal entity; in 2011, efforts of our teams, we showed solid BNP Paribas ZAO decided it would stop operating performances and fi nancial its production of consumer fi nance loans stability in 2011. -

Responsible Investing

La sélection de Responsible Investing SELECTION FROM “L’OPINION” NO. 17 - SUPPLEMENT FROM “L’OPINION” NO. 1105 OF 4 OCTOBER 2017 - MAY NOT BE SOLD SEPARATELY The 2015 Paris climate agreement has accelerated the development of sustainable finance. Bankers, businesses, fund managers: everyone is involved. Green finance, the driving force for a new sustainable world ONU The United Nations’ seventeen Sustainable Development Goals aim to eradicate poverty by 2030. urope is rallying, and furthermore, greater transparen- Environment that’s how important cy of financial institutions and busi- How can we build a bridge between the matter is! This nesses on the way they take sustaina- asset managers concerned with summer, a group of bility into account in their decisions... “Doing more and better with less” responsible investments and busi- experts from the Eu- A huge programme. has become the new mantra of the nesses working to comply with ropean Commission With sustainable finance, Brus- ESG (environmental, social and in Brussels submitted sels clearly wants to move on from the European Commission, which adopted governance) criteria ? Sustainable its first report on sustainable finance. post-subprime crisis years. “The first a package of measures to this effect finance addresses this concern” EThe goal after six months of work: to wave of European Union reforms was Sustainable finance is the answer. identify ways to enshrine this concept, based on the stability and resilience of It brings together SRI (socially which is still somewhat vague, in Euro- the financial system”, comments the responsible investment), soli- pean law. The commission made about European executive. “The Commis- transform our world”. -

Annual Report 2014 BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV 23/02/15 11:50

BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Annual Report 2014 | Annual Report 2014 Report | Annual BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Fortis Paribas BNP AR 2014 Cover.indd 6 23/02/15 11:50 Introduction The BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Report 2014 contains both the audited Consolidated and Non-consolidated Financial Statements, preceded by the Report of the Board of Directors, the Statement of the Board of Directors and a section on Corporate Governance including the composition of the Board of Directors. The audited BNP Paribas Fortis Consolidated Financial Statements 2014, with comparative figures for 2013, prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as adopted by the European Union, are followed by the audited Non-consolidated Financial Statements 2014 of BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV, prepared on the basis of the rules laid down in the Belgian Royal Decree of 23 September 1992 on the annual accounts of credit institutions. All amounts in the tables of the Consolidated Financial All information contained in the BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Statements are denominated in millions of euros, unless Report 2014 relates to the BNP Paribas Fortis statutory stated otherwise. All amounts in the tables of the Non- Consolidated and Non-consolidated Financial Statements consolidated Financial Statements are denominated in and does not cover the contribution of BNP Paribas thousands of euros, unless stated otherwise. Because figures Fortis to the BNP Paribas Group consolidated results, have been rounded off, small discrepancies with previously which can be found on the BNP Paribas website: reported figures may appear. Certain reclassifications www.bnpparibas.com. have been made with regard to the prior year’s Financial Statements in order to make them comparable for the year The BNP Paribas Fortis Annual Report 2014 under review. -

Download Agenda

RiskMinds Europe SESSIONS 11 - 12 May 2021 Online virtual conference PLEASE NOTE THIS IS THE 2021 AGENDA - 11/05/2021 BST (British Summer Time, GMT+1) Interactive morning discussion to kickstart the Interactive roundtable discussion: Embedded conversation and live polling: What’s keeping finance and banking as a service risk managers in Europe awake at night? 13:25 - 13:55 11:30 - 12:00 RiskMinds Europe RiskMinds Europe Participants Join us to take part in live polling, have your say and Host: Peter Rossiter - Chief Risk Officer, Starling share experiences International Participants Host: Christian Bluhm - Group Chief Risk Officer and Risk trends in the EU banking sector amid Member of the Group Executive Board, UBS Covid 13:55 - 14:25 RiskMinds Europe Chair’s opening remarks Participants 12:00 - 12:10 RiskMinds Europe Presenter: Angel Monzon - Head of Risk Analysis and Stress testing, European Banking Authority Participants Presenter: Periklis Thivaios - Partner, True North Partners LLP Brexit and what this means for the regulatory landscape across Europe? Covid-19 recovery, Brexit and key policy 14:25 - 15:10 RiskMinds Europe developments across Europe 12:10 - 12:40 What are the next steps for the UK and Europe in RiskMinds Europe regulatory affairs? Setting the scene... Participants Panellist: Katherine Wolicki - Global Head Financial What’s driving the status quo? Can we collaborate and Model Risk Regulatory Policy and Engagement, better to create more synergy cross border? HSBC Participants Panellist: Barbara Frohn - EMEA Head of -

Musical Chairs in EUROPEAN CREDIT & PRIVATE Equity Q2 2019

MusicaL CHAIRS IN EUROPEAN CREDIT & Private EQUITY Q2 2019 EUROPEAN CREDIT MOVES Iva Horcicova has left ING where she was a VP in High Yield DCM. Her next role, we understand, is yet to be disclosed. CREDIT: BANK Bank of America Merrill Lynch has hired Astghik Khachatryan as a Director in Leveraged Finance, based in Paris. Before joining Adekunle Ademakinwa has left Nomura, where he was Head Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Khachatryan was a Director in the of Credit Debt Syndicate – EMEA, to return to Deutsche Bank Financial Sponsors and Leveraged Finance team at Credit Suisse where he will work for Frazer Ross. Ross was appointed as Head in Paris. of European Flow Syndicate at the bank, adding responsibility for the SSA syndicate business to his existing responsibilities for the Fady Lahame has joined Macquarie to lead its French Advsiory corporate, financials, emerging markets and EMTNs syndicate. and Capital Markets division. Most recently, Lahame worked at Messier Maris & Associés in Paris where he advised on M&A Fabien Antignac was re-hired by Credit Suisse as Head of EU transactions for large corporate clients. Prior to joining Messier in Capital Markets, based in Madrid. Antignac was latterly Head of IB 2015, Lahame spent 19 years at Credit Suisse. for France at Credit Suisse before joining French facility management firmAtalian – a client of the Swiss bank – in October 2018. Mark Lewellen has joined Deutsche Bank as Head of Corporate DCM. Previously, he was Co-Head of Global DCM & Risk Dominik Boskamp has joined Credit Agricole in Frankfurt as Solutions at Barclays. -

European Renewable Energy Market Monthly Market Update

European Renewable Energy Market Monthly Market Update July 2017 ADVANCED ENERGY Monthly Market Update — July 2017 July 2017 Review Corporate Transactions EWE Erneuerbare Energien has acquired Hannover based onshore wind farm developer TurboWind Energie and its 900MW project pipeline. TurboWind will remain an independent unit and complement EWE’s activities EDF Energies Nouvelles has increased its control of French renewable energy company Futuren following a simplified public purchase offer. EDF now holds 87.5% of Futuren capital. Futuren currently operates 745MW of onshore wind assets in Germany, France, Morocco and Italy Marine contractor GeoSea to acquire 100% of offshore wind installation specialist A2Sea. Dong and Siemens have been owners of A2Sea since 2009 Mergers & Acquisitions, and Asset Transactions Asset Transactions Scottish developer Muirhall Energy and partner WWS Renewables have acquired the development assets of UK outfit Infinis from owner Terra Firma. The deal includes six projects totalling 90MW across England, Scotland and Wales as well as a number of projects in the planning process Clean energy investor Glennmont Partners has completed acquisition of a 10MW operational wind farm in central Italy. The wind farm is powered by five Siemens Gamesa G90 turbines and benefits from a 15-year feed-in tariff until 2027 Greencoat UK Wind acquired the 16.4MW Bishopthorpe Wind Farm in England from BayWa for £47 million. The project was commissioned in May and has a forecast net load factor of 35.5% Corporate Transactions European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has provided €28.3 million to Hellenic Petroleum to diversify into renewable energy in Greece. -

Investment Banking

THE ONLY GRADUATE CAREER GUIDE TO Investment Banking 15th Edition Contents The profession Finding the right job Internship profiles Graduate profiles Senior profiles Employer directory Job finder 100s Jobs Find your dream Banking role online today. GRADUATE JOBS | INTERNSHIPS & PLACEMENTS | ADVICE www.insidecareers.co.uk Visit www.insidecareers.co.uk/ban for: JOB EMPLOYER DEADLINES SEARCHJOB DIRECTORYEMPLOYER DEADLINESCALENDAR SEARCH DIRECTORY CALENDAR EVENTS EMAIL VIDEOS, CALENDAREVENTS ALERTSEMAIL BLOGS,VIDEOS, NEWS CALENDAR ALERTS BLOGS, NEWS CONTENTS THE PROFESSION Why Work in Banking? 08 Investment Banking: Opportunities and Challenges 10 Roles in Banking 12 Salaries & Benefits 16 The Age of Fintech 18 The Impact of Brexit on the Financial Services Industry 20 FINDING THE RIGHT JOB Education & Skills 22 The Banking Application Process 24 INTERNSHIP PROFILES Internships & Work Experience 26 Banking Graduate Schemes 30 People Experience Intern – Atom Bank 34 Investment Banking Summer Analyst – Royal Bank of Canada 36 Summer Analyst – Rothschild & Co 38 Analyst – MUFG 40 GRADUATE PROFILES Analyst – Nomura 42 Associate, Investment Banking – J.P. Morgan 44 SENIOR PROFILES Head of Rates Structuring, Global Coordinator – BNP Paribas 46 Financial Advisory Director – Lazard 48 Director – Credit Suisse 50 EMPLOYER DIRECTORY BNP Paribas 53 Commerzbank 54 Credit Suisse 55 J.P. Morgan 56 Lazard 57 Morgan Stanley 58 MUFG 59 Nomura 60 Rothschild & Co 61 JOB FINDER Job Finder 63 The Complete Finance Range GRADUATE JOBS | INTERNSHIPS & PLACEMENTS -

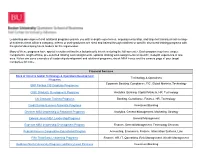

Leadership Development and Rotational Programs Provide You

Leadership development and rotational programs provide you with in-depth experiences, ongoing mentorship, and targeted training across a range of business areas within a company. Interns or post-graduates are hired and trained through rotations or specific structured training programs with the goal of developing future leaders for the organization. Many of these programs have special recruitment timelines but primarily interview during the fall semester. Each program may have unique components, length of time, pre-selected rotating work assignments, optional rotating work assignments or specific, in-depth experience in one area. Below are some examples of leadership development and rotational programs; check MBA Focus and the careers page of your target companies for more. Financial Services Bank of America Global Technology & Operations Development Technology & Operations Programs Corporate Banking, Compliance, FIC, Global Markets, Technology BNP Paribas CIB Graduate Programme CIBC Graduate Development Programs Analytics, Banking, Capital Markets, HR, Technology Citi Graduate Training Programs Banking, Compliance, Finance, HR, Technology Credit Suisse Summer Associate Programs Investment Banking Discover MBA Leadership & Rotational Programs Analytics, General Management, Marketing, Strategy Edward Jones MBA Leadership Programs General Management Experian MBA Leadership Development Program Finance, General Management, Technology Services Federal Reserve Cooperative Educational Program Accounting, Economics, Finance, Information Systems, -

Amsterdam, October 2013

Amsterdam, October 2013 Name organisation BNP Paribas The Netherlands History - 2010 - 2011: expansion BNP Paribas CIB in The Netherlands with Business Centre Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Eindhoven - 2009: Acquisition of Fortis Bank in Belgium and Luxembourg; BNP Paribas is now the first Eurozone bank by deposits, with 4 domestic markets: Belgium, France, Italy and Luxembourg - 2006: Acquisition of BNL in Italy - 1999: creation of BNP Paribas through the merger of BNP and Paribas - 1872: foundation of Paribas through the merger of Nederlandse Krediet- en Deposito Bank and Banque de Paris - 1869: foundation Banque de Paris - 1863: foundation Nederlandse Krediet- en Deposito Bank (Amsterdam) Head Office The Netherlands Herengracht 595 1017 CE Amsterdam Head Office international 16, Boulevard des Italiens 75009 Paris Coverage BNP Paribas is present in nearly 80 countries, on 5 continents Director The Netherlands André Boulanger CEO BNP Paribas The Netherlands since April 1 st , 2010 Director international Jean-Laurent Bonnafé (1961) Chief Executive Officer since 2011 Number of employees - The Netherlands: around 1.200 staff (including subsidiaries) - International: 190,000 (68% outside France and 145,000 in Europe) Companies The Netherlands - BNP Paribas: corporate & investment banking (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Eindhoven) - Arval (Houten): car leasing - BNP Paribas Cardif (Oosterhout): insurances - BNP Paribas Factor (Breda): factoring - BNP Paribas Investment Partners (Amsterdam): asset management - BNP Paribas Leasing Solutions (Den Bosch): operational -

Introduction Introduction Contents

GTR Directory 2018-19 GTR Directory 2018-19 Contents London Forfaiting Company Ltd 159 Union Bank of Nigeria plc 232 The London Institute of Banking & Finance 160 Union Bank UK plc 235 Financial Institutions & Advisory Commonwealth Bank of Australia 82 Maersk Trade Finance A/S 161 United Overseas Bank Limited 235 The Co-operative Bank of Kenya Ltd 83 Abanca 10 Mashreq 162 United Bank for Africa 236 Coronation Merchant Bank 84 Absa 11 Mastercard 163 VTB Bank 238 Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 86 Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank 12 The Mauritius Commercial Bank Limited 164 Wells Fargo 240 Credit Europe Bank NV 88 Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank 14 Mizuho Bank, Ltd. 166 Wilben Trade Limited 242 Credit Suisse (Switzerland) Ltd. 88 Access Bank plc 16 Maybank 168 Woodsford TradeBridge Ltd 242 Crown Agents Bank 89 Advantage Delaware LLC 18 MUFG Bank, Ltd. 169 Westpac Banking Corporation 244 DBS Bank 90 Africa Trade Finance Limited 19 National Bank of Fujairah PJSC 172 Wyelands Bank plc 246 Deutsche Bank 92 AfrAsia Bank 20 Natixis 173 XacBank 248 Deloitte 94 African Export Import Bank 22 NatWest 174 Yapı ve Kredi Bankası A.Ş 249 DF Deutsche Forfait GmbH 95 AIC Finanz GmbH 24 NIC Bank Kenya 175 Zürcher Kantonalbank 249 Diamond Bank plc 96 Al Ahli Bank of Kuwait K.S.C.P. 25 Nedbank CIB Johannesburg 176 Zenith Bank (UK) Limited 250 Introduction Diligence 97 Introduction Al Salam Bank Bahrain BSC 25 Nedbank CIB London 176 Zenith Bank (UK) Limited – (DIFC Branch) 250 DMCC 99 Akbank 26 Orbian Management Ltd 178 EBI SA Groupe 100 Akbank AG 27 ODDO BHF -

DNCA Finance Appoints a General Counsel

Press release July 11, 2018 DNCA Finance appoints a General Counsel Paris, July 11, 2018 - Natixis Investment Managers’ affiliate DNCA Finance, which has more than one hundred and twenty staff across three offices in Paris, Luxembourg and Milan, today announces the appointment of Sébastien Launay as General Counsel. He will be in charge of a team of five staff and will be tasked with managing legal aspects on products and services, distribution and partnerships, contracts, corporate governance, etc., for all companies in the DNCA group i.e. DNCA Finance, DNCA Finance Luxembourg, DNCA Finance Milan and DNCA Courtage. Sébastien is 47 years’ old, and holds a Masters’ degree in Business Law and an MBA. He boasts 21 years’ experience in the Société Générale and BNP Paribas groups and has particularly strong insight into the Asset Management sector. Sébastien began his career in 1997 in the legal department for Structured Products on Equities/Indices/Funds at Société Générale CIB, where he played an active role in setting up and developing Lyxor Asset Management, before joining Société Générale Asset Management. In 2011, he joined BNP Paribas CIB as Head of GECD Legal Structured and Flow Solutions, then took part in setting up the BNP Paribas Asset Management Private Debt and Real Assets Funds. Sébastien Launay was appointed group General Counsel at DNCA in June 2018. Press release July 11, 2018 About DNCA: DNCA is a French asset management company set up in 2000 by wealth-management specialists acting on behalf of private and institutional investors. With a defensive slant, the company seeks to optimize the risk/return ratio on its portfolios.