Doctor of Philosophy in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

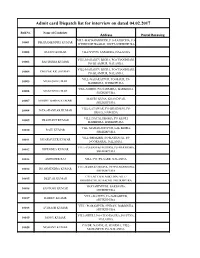

Dispatch List 04-02-2017.Pdf

Admit card Dispatch list for interview on dated 04.02.2017 Roll No. Name of Candidate Address Postal Receving VILL-MAHANANDPUR, P.O-LALBIGHA, P.S- 10001 DHARAMENDRA KUMAR SHEIKHOPURSARAI, DISTT-SHEIKHPURA 10002 GUDDU KUMAR VILL+PO+PS-SARMERA, NALANDA. VILL-MAHADEV BIGHA, PO-CHANDHARI, 10003 RAVINDRA KUMAR PS-ISLAMPUR, NALANDA. VILL-MAHADEV BIGHA, PO-CHANDHARI, 10004 DEEPAK KR. SAURAV PS-ISLAMPUR, NALANDA. VILL-NASARATPUR, PO-MAUR, PS- 10005 MUKESH KUMAR BARBIGHA, SHEIKHPURA. VILL-SHIDIH, PO-SARMERA, BARBIGHA, 10006 MUKESH KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. MAHTO KUNA, KHAND PAR, 10007 MADHU BARSA KUMARI SHEIKHPURA. VILL-LATAWAR, PO-BHADSENI, PS- 10008 JATA SHANKAR KUMAR HISUA, NAWADA. VILL-DAYALI BIGHA, PO-KEOTI, 10009 PRASHANT KUMAR BARBIGHA, SHEIKHPURA. VILL-MAHANAND PUR, LAL BIGHA, 10010 RAJU KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. VILL-BHAKHRI, PO-KATHAULI, PS- 10011 DHARMVEER KUMAR NOORSARAI, NALANDA. VILL+PO-SAMAS BUJURG, PS-BARBIGHA, 10012 DIPENDRA KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. 10013 ABHISHEK RAJ VILL+PO+PS-SARE, NALANDA. VILL-BABHAN BIGHA, PS+PO-BARBIGHA, 10014 DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. C/O LATE BALMIKI JHA, VILL- 10015 DEEPAK KUMAR BHADRATHI, KUSADHI, SHEIKHPURA. MOH-SHIVPURI, BARBIGHA, 10016 SANTOSH KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. VILL+PO-TEUS, PS-JAIRAMPUR, 10017 RAJEEV KUAMR SHEIKHPURA. VILL+PO-RAMPUR, SINDAY, BARBIGHA, 10018 AVINASH KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. VILL-SIHULI, PO-CHANDAURA, PS-VENA, 10019 MONU KUMAR NALANDA. C/O DR. NAND LAL SHARMA, VILL- 10020 NISHANT KUMAR MOHANPUR, PO-NALANDA. VILL-JAMALPUR, PO-LARI, PS-KURTHA, 10021 AJIT KUMAR ARWA. 10022 ASHOK KUMAR VILL+PO-ORO, PS-HISUA, NAWADA. VILL-JORARPUR, PO-DAILI, PS-HARNAUT, 10023 SANJEEV KUMAR NALANDA. VILL-AHIYAPUR, KUTAUT, BARBIGHA, 10024 KUNDAN KUMAR SHEIKHPURA. VILL-PURUSHOTAMPUR, PO-DEWARA, 10025 MANOJ KUMAR GHOSHI, JEHNABAD. -

2012 Rakhine State Riots

2012 Rakhine State riots The 2012 Rakhine State riots were a series of conflicts 2012 Rakhine State riots primarily between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar, though by October Part of the Persecution of Muslims in Muslims of all ethnicities had begun to be targeted.[5][6][7] The Myanmar riots started came after weeks of sectarian disputes including a Location Rakhine State, gang rape and murder of a Rakhine woman by Rohingya Myanmar [8] Muslims. On 8 June 2012, Rohingyas started to protest from Date 8 June 2012 Friday's prayers in Maungdaw township. More than a dozen (UTC+06:30) residents were killed after police started firing.[9] State of Attack Religious emergency was declared in Rakhine, allowing military to type [10][11] participate in administration of the region. As of 22 Deaths June: 88[1][2][3] August, officially there had been 88 casualties – 57 Muslims and October: at least 80[4] [1] 31 Buddhists. An estimated 90,000 people were displaced by 100,000 displaced[4] the violence.[12][13] About 2,528 houses were burned; of those, 1,336 belonged to Rohingyas and 1,192 belonged to Rakhines.[14] Rohingya NGOs have accused the Burmese army and police of playing a role in targeting Rohingya through mass arrests and arbitrary violence[15] though an in-depth research by the International Crisis Group reported that members of both communities were grateful for the protection provided by the military.[16] While the government response was praised by the United States and European Union,[17][18] NGOs were more critical, citing discrimination of Rohingyas by the previous military government.[17] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and several human rights groups rejected the President Thein Sein's proposal to resettle the Rohingya abroad.[19][20] Fighting broke out again in October, resulting in at least 80 deaths, the displacement of more than 20,000 people, and the burning of thousands of homes. -

Office of the District Transport Officer SARAIKELA Demand Notice District

Office of the District Transport Officer SARAIKELA Demand Notice Memo No. Dated: 26--Dec-2016 To, BINITA KUMARI GUPTA S/O W/O NAVEEN KUMAR R/O C/O RANJAY THAKUR WARD NO.7 RAYDIH,ADIYAPUR DIST-SERAIKELLA-KHARSAWAN Dist- JHARKHAND Pin 831013 It appears from the office record that you are the registered owner of vehicle no. JH22A 2488 ( BUS ) and it also appears that you have not paid the Road Tax and Additional Tax of the above vehicle from 04-SEP- 2013 to 15-DEC-2016 which is Rs.258157 (in words Two Lakh Fifty-Eight Thousand One Hundred Fifty- Seven only ) with penalty. You are hereby directed to pay the aforesaid amount an or before 25-Jan-2017 failure to which a proper legal action may be taken against you for recovery of the demand. District Transport Officer Office of the District Transport Officer SARAIKELA Demand Notice Memo No. Dated: 26--Dec-2016 To, AMAR PRATAP SINGH S/O S/O S.P. SINGH R/O C/O NIRAJ KR. GOUTAM H.NO.68/2/3 RO,AD NO.10 ADITYAPUR 1 DIST-S.KHAR. Dist- JHARKHAND Pin It appears from the office record that you are the registered owner of vehicle no. JH22A 3921 ( BUS ) and it also appears that you have not paid the Road Tax and Additional Tax of the above vehicle from 12-OCT- 2016 to 15-DEC-2016 which is Rs.12828 (in words Twelve Thousand Eight Hundred Twenty-Eight only ) with penalty. You are hereby directed to pay the aforesaid amount an or before 25-Jan-2017 failure to which a proper legal action may be taken against you for recovery of the demand. -

Office of the Civil Surgeon, West Singhbhum, Chaibasa List of Eligible Candidate for the Post of LAB TECHNICIAN CHC NCD CLINIC Post Code - 15, Advt

Office of the Civil Surgeon, West Singhbhum, Chaibasa List of Eligible Candidate for the Post of LAB TECHNICIAN CHC NCD CLINIC Post Code - 15, Advt. No 01 2017 Technical Qualification Inter Jharkhand (DMLT) State Experie Knowle Form Paramedic nce Sl. Father's Date of Home Residen Categor dge of Amo Sl. Name Mobile no Permanent Address Present Address al counl, (Min. Remarks Bank Name DD No DD Date No. Name Birth District tial y Compu unt No. Marks Marks Ranchi - 02 Total Total ter Obtaine % Obtaine % Registrato Years) Marks Marks d d n AT - SURYA NARSING VILL - DUDRI, PO - TOKLO, HOME, THANA ROAD, SUSHIL WEST PNB, NIRANJAN CHAKRADHARPUR, DIST - WARD NO 02, PO - YES OBC 04 Y 01 1 4 KUMAR 12-Jan-1990 9934978075 SINGHB 500 280 56.00% 700 503 71.86% NA NA ASANTALI 818130 11-Sep-2017 MAHTO WEST SINGHBHUM, CHAKRADHARPUR, DIST - (SDO) (SDO) M MAHTO HUM A 400.00 JHARKHAND WEST SINGHBHUM, JHARKHAND VILL - ABHAYPUR, PO - VILL - ABHAYPUR, PO - SANJAY URKIYA, PS - URKIYA, PS - WEST CANARA PRAYAG YES OBC 2 59 KUMAR 15-Feb-1985 9438509940 MANOHARPUR, DIST - MANOHARPUR, DIST - SINGHB 900 460 51.11% 700 422 60.29% NA 02 M NA BANK, 967913 09.16.2017 MAHTO (SDO) (CO) MAHTO WEST SINGHBHUM, WEST SINGHBHUM, HUM CHAIBASA 400.00 JHARKHAND JHARKHAND VILL - BHOGRA, VILL - GUA, GUASAI, PO - MHANTISAI, PO - WEST GEETA KHAGESHW GUA, DIST - WEST 03 Y 02 3 75 27-Dec-1986 7091265622 JAGANNATHPUR, DIST - SINGHB 500 235 47.00% 1900 1409 74.16% NA NA SBI, GUA 407515 16-Sep-2017 KUMARI AR PAN SINGHBHUM, M WEST SINGHBHUM, HUM 400.00 JHARKHAND JHARKHAND VILL - SIDMA BARU -

Understanding Riot in the Age of the Digital

Understanding Riot in the Age of the Digital MANISHA MADAPATHI ABSTRACT non-religious sentiments can be observed repeatedly in Maharashtra, Assam and other parts of the North-East. This paper tries to locate the impact of new media Ashish Nandy, in his essay ‘The Politics of Secularism and technologies within the phenomenon of mass the Recovery of Religious Tolerance’, makes a distinction mobilization, focusing on riots in India. The cases I between religion as faith and religion as ideology, which examine are from the recent past, dating not more than is analogous to the distinction made between syncretic five years ago. These technological innovations have popular religion and communal ideology. generated new vocabularies in which one can perceive Within this context of uncertainty to life in communities, riots in the subcontinent. I try to correlate concepts of I would like to introduce another very crucial concept digital with traditional social sciences resulting in a with regard to information systems. Contrary to popular hybrid discourse on the current day riots in India. belief, riots are not a spontaneous occurrence, there is a South Asia, comprising a large arbitrary landmass, great deal of planning and a systematic dissemination is home to a multitude of cultures, races, languages, of information that function methodically. Spreading ethnicities, and religions. This region on the geographic rumours and delivering inflammatory speeches in areas map is celebrated for the diversity it tolerates, which itself already torn by communal differences have been tools also throws challenges at its communities to keep them of the old trade. What is of immediate concern though intact within the milieu of differences and the fear of is the coming of newer forms of communication with the alienation. -

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal -..:: Global Group Of

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal (A Sub-Himalayan Tract) Edited by Publish by Global Vision Publishing House Sukhbilas Barma Greater Kuch Bihar—A Utopian Movement? Sukhbilas Barma IT HAS happened every now and then—one movement followed by the other. This part of the country popularly known as North Bengal, inhabited by the major ethnic group of people, the Rajbanshis, has gone through different phases of various movements and mainly ethnic movements. One can be reminded of the Uttar Khanda movement, a movement of a section of the Rajbanshis led by Panchanan Mallik. The movement was basically on the socio-economic- political issues, the feeling of deprivation of the sons of the soil. This continued for some time; the Government paid some amount of attention to the problems of the region; people got swayed by the left ideologies, and the movement lost ground. Then came Kamtapuri movement in late 90’s, based on ethnic sentiments, which were related primarily to the feeling of subordination of the Rajbanshi language and culture. Based on the linguistic theory propounded by Dharmanarayan Barma, the leaders of Kamtapuri movement led by Atul Roy shook the socio-political environment of Dr. Sukhbilas Barma: A retired I.A.S Officer, Dr. Barma held important positions in the Government of west Bengal. 336 Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal North Bengal vigorously. The well-off sections of the Rajbanshis have lost their lands and prestige to the non- Rajbanshis hailing from East Pakistan. The poverty stricken youths have had to leave their mother land in search of livelihood. -

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh

Name of Regional Directorate of NSS, Lucknow State - Uttar Pradesh Regional Director Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. A.K. Shroti, Regional [email protected] 0522-2337066, 4079533, Regional Directorate of NSS [email protected] 09425166093 Director, NSS 8th Floor, Hall No. [email protected] Lucknow 1, Sector – H, Kendriya Bhawan, Aliganj Lucknow – 226024 Minister Looking after NSS Name Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Number Dr. Dinesh 99-100, Mukhya 0522-2213278, 2238088 Sharma, Dy. Bhawan, Vidhan C.M. and Bhawan, Lucknow Minister, Higher Education Smt. Nilima 1/4, B, Fifth Floor, Katiyar, State Bapu Bhawan, Minister, Lucknow 0522-2235292 Higher Education PS/Secretary Dealing with NSS Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline Secretary with Number State Smt. Monika Garg 64, Naveen [email protected] 0522-2237065 Bhawan,Lucknow Sh. R. Ramesh Bahukhandi First Floor, [email protected] 0522-2238106 Kumar Vidhan Bhawan, Lucknow State NSS Officers Name of the Address Email ID Telephone/Mobile/Landline SNO Number Dr. (Higher Education) [email protected] 0522-2213350, 2213089 Anshuma Room No. 38, 2nd [email protected] m 9415408590 li Sharma Floor, Bahukhandiya anshumali.sharma108@g Bhawan, Vidhan mail Bhawan, Lucknow - .com 226001 Programme Coordinator , NSS at University Level Name of the University Name Email ID Telephone/Mobi Programme le/Landline Coordinator Number Dr. Ramveer S. Dr.B.R.A.University,Agra [email protected] 09412167566 Chauhan Dr. Rajesh Kumar Garg Allahabad University, [email protected] 9415613194 Allahabad Shri Umanath Dr.R.M.L. Awadh [email protected] 9415364853 (Registrar) University, Faizabad Dr. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was the first President of His Excellency India, in office from 1952 to 1962.[1] He was an Indian political leader, and lawyer by training, Prasad joined the Indian National Congress during the Indian Rajendra Prasad Independence Movement and became a major leader from the region of Bihar. A supporter of Mahatma Gandhi, Prasad was imprisoned by British authorities during the Salt Satyagraha of 1931 and the Quit India movement of 1942. After the 1946 elections, Prasad served as Minister of Food and Agriculture in the central government. Upon independence in 1947, Prasad was elected as President of the Constituent Assembly of India, which prepared the Constitution of India and served as its provisional parliament. When India became a republic in 1950, Prasad was elected its first president by the Constituent Assembly. Following the general election of 1951, he was elected president by the electoral college of the first Parliament of India and its state legislatures. As president, Prasad established a tradition of non-partisanship and independence for the office-bearer, and retired from Congress party politics. Although a ceremonial head of state, Prasad encouraged the development of 1st President of India education in India and advised the Nehru government on several occasions. In 1957, In office Prasad was re-elected to the presidency, becoming the only president to serve two 26 January 1950 – 13 May 1962 full terms.[2] Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru Vice President Sarvepalli -

'Spaces of Exception: Statelessness and the Experience of Prejudice'

London School of Economics and Political Science HISTORIES OF DISPLACEMENT AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL SPACE: ‘STATELESSNESS’ AND CITIZENSHIP IN BANGLADESH Victoria Redclift Submitted to the Department of Sociology, LSE, for the degree of PhD, London, July 2011. Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 For Pappu 2 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis, presented for examination for the degree of PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is entirely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ____________________ ____________________ Victoria Redclift Date 3 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Abstract In May 2008, at the High Court of Bangladesh, a ‘community’ that has been ‘stateless’ for over thirty five years were finally granted citizenship. Empirical research with this ‘community’ as it negotiates the lines drawn between legal status and statelessness captures an important historical moment. It represents a critical evaluation of the way ‘political space’ is contested at the local level and what this reveals about the nature and boundaries of citizenship. The thesis argues that in certain transition states the construction and contestation of citizenship is more complicated than often discussed. The ‘crafting’ of citizenship since the colonial period has left an indelible mark, and in the specificity of Bangladesh’s historical imagination, access to, and understandings of, citizenship are socially and spatially produced. -

Community, Nation and Politics in Colonial Bihar (1920-47)

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 COMMUNITY, NATION AND POLITICS IN COLONIAL BIHAR (1920-47) Md Masoom Alam, PhD, JNU Abstract The paper is an attempt to explore, primarily, the nationalist Muslims and their activities in Bihar, since 1937 till 1947. The work, by and large, will discuss the Muslim personalities and institutions which were essentially against the Muslim League and its ideology. This paper will be elaborating many issues related to the Muslims of Bihar during 1920s, 1930s and 1940s such as the Muslim organizations’ and personalities’ fight for the nation and against the League, their contribution in bridging the gulf between Hindus and Muslims and bringing communal harmony in Bihar and others. Moreover, apart from this, the paper will be focusing upon the three core issues of the era, the 1946 elections, the growth of communalism and the exodus of the Bihari Muslims to Dhaka following the elections. The paper seems quite interesting in terms of exploring some of the less or underexplored themes and sub-themes on colonial Bihar and will certainly be a great contribution to the academia. Therefore, surely, it will get its due attention as other provinces of colonial India such as U. P., Bengal, and Punjab. Introduction Most of the writings on India’s partition are mainly focused on the three provinces of British India namely Punjab, Bengal and U. P. Based on these provinces, the writings on the idea of partition and separatism has been generalized with the misperception that partition was essentially a Muslim affair rather a Muslim League affair.