THE RAINBOW FLAG of the INCAS by Gustav Tracchia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorandum of the Secretariat General on the European Flag Pacecom003137

DE L'EUROPE - COUNCIL OF EDMFE Consultative Assembly Confidential Strasbourg,•15th July, 1951' AS/RPP II (3) 2 COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PROCEDURE AND PRIVILEGES Sub-Committee on Immunities I MEMORANDUM OF THE SECRETARIAT GENERAL ON THE EUROPEAN FLAG PACECOM003137 1.- The purpose of an Emblem There are no ideals, however exalted in nature, which can afford to do without a symbol. Symbols play a vital part in the ideological struggles of to-day. Ever since there first arose the question of European, organisation, a large number of suggestions have more particularly been produced in its connection, some of which, despite their shortcomings, have for want of anything ;. better .been employed by various organisations and private ' individuals. A number of writers have pointed out how urgent and important it is that a symbol should be adopted, and the Secretariat-General has repeatedly been asked to provide I a description of the official emblem of the Council of Europe and has been forced to admit that no such emblem exists. Realising the importance of the matter, a number of French Members of Parliament^ have proposed in the National Assembly that the symbol of the European Movement be flown together with the national flag on public buildings. Private movements such as'the Volunteers of Europe have also been agitating for the flying of the European Movement colours on the occasion of certain French national celebrations. In Belgium the emblem of the European Movement was used during the "European Seminar of 1950" by a number of *•*: individuals, private organisations and even public institutions. -

PWA Unity Diversity Publication July 2017

July 2017 Volume 1, Issue 3 Unity: Cultivating Diversity and Inclusion in PWA Hilo, Hawaii LGBT Film Screening Hilo, Hawaii recognized LGBT Month by holding a special screening of the film Limited Partnerships. Limited Partnership is the love story between Filipino-American Richard Adams and his Australian husband, Tony Sullivan. In 1975, thanks to a courageous county clerk in Boulder, CO, Richard and Tony were one of the first same-sex couples in the world to be legally married. Richard immediately filed for a green card for Tony based on their marriage. But unlike most heterosexual married couples who easily file petitions and obtain green cards, Richard received a denial letter from the Immi- gration and Naturalization Service stating, “You have failed to establish that a bona AREA DIRECTOR’S fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” Outraged at the tone, tenor CORNER: and politics of this letter and to prevent Tony’s impending deportation, the couple sued the U.S. government. This became the first federal lawsuit seeking equal treat- Maintaining a workplace that wel- ment for a same-sex marriage in U.S. history. comes diversity in all forms is an im- Over four decades of legal challenges, Richard and Tony figured out how to maintain portant component of attracting high- ly-qualified applicants for our job their sense of humor, justice and whenever possible, their privacy. Their personal vacancies. Celebrations of Special tale parallels the history of the LGBT marriage and immigration equality move- Emphasis Program months contribute ments, from the couple signing their marriage license in Colorado, to the historic to this effort by enhancing our appre- U.S. -

1 Indigenous Litter-Ature 2 Drinking on the Pre-Mises: the K'ulta “Poem” 3 Language, Poetry, Money

Notes 1 Indigenous Litter-ature 1 . E r n e s t o W i l h e l m d e M o e s b a c h , Voz de Arauco: Explicación de los nombres indí- genas de Chile , 3rd ed. ( Santiago: Imprenta San Francisco, 1960). 2. Rodolfo Lenz, Diccionario etimológico de las voces chilenas derivadas de len- guas indígenas americanas (Santiago: Universidad de Chile, 1910). 3 . L u d o v i c o B e r t o n i o , [ 1 6 1 2 ] Vocabulario de la lengua aymara (La Paz: Radio San Gabriel, 1993). 4 . R . S á n c h e z a n d M . M a s s o n e , Cultura Aconcagua (Santiago: Centro de Investigaciones Diego Barros Arana y DIBAM, 1995). 5 . F e r n a n d o M o n t e s , La máscara de piedra (La Paz: Armonía, 1999). 2 Drinking on the Pre-mises: The K’ulta “Poem” 1. Thomas Abercrombie, “Pathways of Memory in a Colonized Cosmos: Poetics of the Drink and Historical Consciousness in K’ulta,” in Borrachera y memoria , ed. Thierry Saignes (La Paz: Hisbol/Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 1983), 139–85. 2 . L u d o v i c o B e r t o n i o , [ 1 6 1 2 ] Vocabulario de la lengua aymara (La Paz: Radio San Gabriel, 1993). 3 . M a n u e l d e L u c c a , Diccionario práctico aymara- castellano, castellano-aymara (La Paz- Cochabamba: Los Amigos del Libro, 1987). -

Executive Office of the Governor Flag Protocol

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR FLAG PROTOCOL Revised 9/26/2012 The Florida Department of State is the custodian of the official State of Florida Flag and maintains a Flag Protocol and Display web page at http://www.dos.state.fl.us/office/admin-services/flag-main.aspx. The purposes of the Flag Protocol of the Executive Office of the Governor are to outline the procedures regarding the lowering of the National and State Flags to half-staff by directive; to provide information regarding the display of special flags; and to answer frequently asked questions received in this office about flag protocol. Please direct any questions, inquires, or comments to the Office of the General Counsel: By mail: Executive Office of the Governor Office of the General Counsel 400 South Monroe Street The Capitol, Room 209 Tallahassee, FL 32399 By phone: 850.717.9310 By email: [email protected] By web: www.flgov.com/flag-alert/ Revised 9/26/2012 NATIONAL AND STATE FLAG POLICY By order of the President of the United States, the National Flag shall be flown at half-staff upon the death of principal figures of the United States government and the governor of a state, territory, or possession, as a mark of respect to their memory. In the event of the death of other officials or foreign dignitaries, the flag is to be flown at half-staff according to presidential instructions or orders, in accordance with recognized customs or practices not inconsistent with law. (4 U.S.C. § 7(m)). The State Flag shall be flown at half-staff whenever the National Flag is flown at half-staff. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Hunting Deer in California

HUNTING DEER IN CALIFORNIA We hope this guide will help deer hunters by encouraging a greater understanding of the various subspecies of mule deer found in California and explaining effective hunting techniques for various situations and conditions encountered throughout the state during general and special deer seasons. Second Edition August 2002 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Arnold Schwarzenegger, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME L. Ryan Broddrick, Director WILDLIFE PROGRAMS BRANCH David S. Zezulak, Ph.D., Chief Written by John Higley Technical Advisors: Don Koch; Eric Loft, Ph.D.; Terry M. Mansfield; Kenneth Mayer; Sonke Mastrup; Russell C. Mohr; David O. Smith; Thomas B. Stone Graphic Design and Layout: Lorna Bernard and Dana Lis Cover Photo: Steve Guill Funded by the Deer Herd Management Plan Implementation Program TABLE OF CON T EN T S INTRODUCT I ON ................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: THE DEER OF CAL I FORN I A .........................................................................................................7 Columbian black-tailed deer ....................................................................................................................8 California mule deer ................................................................................................................................8 Rocky Mountain mule deer .....................................................................................................................9 -

Anomalous Attitude Motion of the Polar Bear Satellite

JOHN W. HUNT, JR., and CHARLES E. WILLIAMS ANOMALOUS ATTITUDE MOTION OF THE POLAR BEAR SATELLITE After an initial three-month period of nominal performance, the Polar BEAR satellite underwent large attitude excursions that finally resulted in its tumbling and restabilizing upside down. This article describes the attitude motion leading up to the anomaly and the subsequent reinversion effort. INTRODUCTION body (i.e., one with unequal principal moments of iner tia). Its principal axis of minimum inertia is aligned with The Polar BEAR satellite was launched successfully the local vertical (an imaginary line from the earth's mass from Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., in November center to the satellite's mass center), and its principal axis 1986. A Scout launch vehicle placed Polar BEAR into of maximum inertia is aligned with the normal-to-the a circular, polar orbit at an altitude of lcxx) kIn. The satel orbit plane. 1-3 lite's four instruments are designed to yield data on RF Many spacecraft built by APL have used extendable communications, auroral displays, and magnetic fields in booms to achieve a favorable moment-of-inertia distri the earth's polar region. bution, that is, an inertia ellipsoid where the smallest prin The Polar BEAR attitude control system is required cipal moment of inertia is at least an order of magnitude to maintain an earth-pointing orientation for the on-board less than the others. The Polar BEAR satellite includes instruments. For nominal operation, Polar BEAR is stabi a constant-speed rotor with its spin axis aligned with the lized rotationally to within ± 10° about any of three or spacecraft's y (pitch) axis. -

THE LION FLAG Norway's First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard

THE LION FLAG Norway’s First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard On 27 February 1814, the Norwegian Regent Christian Frederik made a proclamation concerning the Norwegian flag, stating: The Norwegian flag shall henceforth be red, with a white cross dividing the flag into quarters. The national coat of arms, the Norwegian lion with the yellow halberd, shall be placed in the upper hoist corner. All naval and merchant vessels shall fly this flag. This was Norway’s first national flag. What was the background for this proclamation? Why should Norway have a new flag in 1814, and what are the reasons for the design and colours of this flag? The Dannebrog Was the Flag of Denmark-Norway For several hundred years, Denmark-Norway had been in a legislative union. Denmark was the leading party in this union, and Copenhagen was the administrative centre of the double monarchy. The Dannebrog had been the common flag of the whole realm since the beginning of the 16th century. The red flag with a white cross was known all over Europe, and in every shipping town the citizens were familiar with this symbol of Denmark-Norway. Two variants of The Dannebrog existed: a swallow-tailed flag, which was the king’s flag or state flag flown on government vessels and buildings, and a rectangular flag for private use on ordinary merchant ships or on private flagpoles. In addition, a number of special flags based on the Dannebrog existed. The flag was as frequently used and just as popular in Norway as in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars Result in Political Changes in Scandinavia At the beginning of 1813, few Norwegians could imagine dissolution of the union with Denmark. -

The Aztecs Gave the Tribe the Name Olmec

Mayan, Incan, and Aztec Civilizations: The Arrival of Man Alternate Version Download The Arrival of Man Crossing the Bering Strait Land Bridge Giant ice caps once covered both the Arctic and Antarc- tic regions of the earth. This was over 50,000 years ago. The levels of the oceans were lower than today. Much of the earth’s water was trapped in the polar ice caps. The lower water level showed a piece of land that connected Siberia to Alaska. To- day this area is once again under water. It is called the Bering Strait. Many scientists believe that early humans crossed over this land bridge. Then they began to spread out and settle in what is now North America. These people then moved into Central and South America. The Bering Strait land bridge was covered with water again when the ice caps thawed. This happened at the end of the Ice Age around 8,000 B.C. Today, we call the first people who settled in the West- ern Hemisphere Paleo-Indians. They are also called Paleo- Americans. Paleo is a prefix from the Greek language mean- As tribes migrated throughout North, ing “old.” The term Indian comes from the time of Columbus’ Central, and South America, they dis- voyages. He thought he had landed in India. Other names for covered agriculture and learned how to native people include Native Americans and First Nations. make stone tools and clay pottery. Each tribe or cultural group has its own name for its people. Hunting and Gathering The Paleo-Indians were hunters and gatherers. -

Arte Rupestre, Etnografía Y Memoria Colectiva: El Caso De Cueva De Las Manos, Patagonia Argentina

Rev. urug. antropología etnografía, ISSN 2393-6886, 2021, Año VI – Nº 1:71–85 DOI: 10.29112/RUAE.v6.n1.4 Estudios y Ensayos Arte rupestre, etnografía y memoria colectiva: el caso de Cueva de las Manos, Patagonia Argentina ROCK ART (CAVE PAINTING), ETHNOGRAPHY AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY. CASE OF STUDY: CUEVA DE LAS MANOS, PATAGONIA, ARGENTINA ARTE RUPESTRE, ETNOGRAFIA E MEMÓRIA COLETIVA. O CASO DE CUEVA DE LAS MANOS, PATAGÔNIA, ARGENTINA 1 Patricia Schneier 71 Agustina Ponce2 Carlos Aschero3 1 Investigadora independiente; Licenciada en Cs. Antropológicas, FFyL-UBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0003-0071-5455. 2 Becaria en el Instituto Superior de Estudios Sociales (ISES)CONICET/UNT e Instituto de Arqueología y Museo (IAM), FCN e IML-UNT, Tucumán, Argentina. chuen@ outlook.com.ar, ORCID: 0000-0002-1740-6408. 3 Investigador principal en el Instituto Superior de Estudios Sociales(ISES)CONICET/UNT e Instituto de Arqueología y Museo (IAM), FCN e IML-UNT, Tucumán, Argentina. [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0001-9872- 9438. RESUMEN Cueva de las Manos (Patagonia Argentina) es un emblemático sitio que ha sido declarado Patrimonio de la Humanidad por UNESCO. En él se presenta una gran cantidad de paneles de arte rupestre realizados en distintos momentos, entre 9400 y 2500 años atrás. Sobre el amplio repertorio de figuras y escenas que se representaron en los mismos, seleccionamos dos temas: escenas de caza y guanacas preñadas en relación con los negativos de manos. Tomando como referencia registros documentales etnográficos que preservaron narraciones míticas del pueblo P. Schneier, A. Ponce, C. Aschero – Arte rupestre, etnografía y memoria colectiva: el caso de Cueva… Tehuelche, además de los relatos de cronistas y viajeros, proponemos líneas interpretativas afines con aquellos temas del arte rupestre, realizados miles de años atrás. -

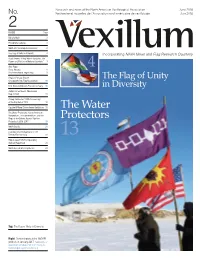

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

The Incas.Pdf

THE INCAS THE INCAS By Franklin Pease García Yrigoyen Translated by Simeon Tegel The Incas Franklin Pease García Yrigoyen © Mariana Mould de Pease, 2011 Translated by Simeon Tegel Original title in Spanish: Los Incas Published by Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2007, 2009, 2014, 2015 © Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2015 Av. Universitaria 1801, Lima 32 - Perú Tel.: (51 1) 626-2650 Fax: (51 1) 626-2913 [email protected] www.pucp.edu.pe/publicaciones Design and composition: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú First English Edition: January 2011 First reprint English Edition: October 2015 Print run: 1000 copies ISBN: 978-9972-42-949-1 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú N° 2015-13735 Registro de Proyecto Editorial: 31501361501021 Impreso en Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa Pasaje María Auxiliadora 156, Lima 5, Perú Contents Introduction 9 Chapter I The Andes, its History and the Incas 13 Inca History 13 The Predecessors of the Incas in the Andes 23 Chapter II The Origin of the Incas 31 The Early Organization of Cusco and the Formation of the Tawantinsuyu 38 The Inca Conquests 45 Chapter III The Inca Economy 53 Labor 64 Agriculture 66 Agricultural Technology 71 Livestock 76 Metallurgy 81 The Administration of Production 85 Storehouses 89 The Quipus 91 Chapter IV The Organization of Society 95 The Dualism 95 The Inca 100 The Cusco Elite 105 The Curaca: Ethnic Lord 109 Inca and Local Administration 112 The Population and Population