'Muzak for Frogs'—Representations of 'Nature' in Decoder (1984)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

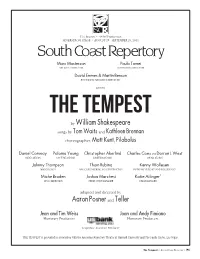

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Independent Experimental Film (Animation and Live-Action) Remains the Great Hardly-Addressed Problem of Film Preservation

RESTORING EXPERIMENTAL FILMS by William Moritz (From Anthology Film Archives' "Film Preservation Honors" program, 1997) Independent experimental film (animation and live-action) remains the great hardly-addressed problem of film preservation. While million-dollar budgets digitally remaster commercial features, and telethon campaigns raise additional funds from public donations to restore "classic" features, and most of the film museums and archives spend their meager budgets on salvaging nitrates of early live-action and cartoon films, thousands of experimental films languish in desperate condition. To be honest, experimental film is little known to the general public, so a telethon might not engender the nostalgia gifts that pour in to the American Movie Classics channel. But at their best, experimental films constitute Art of the highest order, and, like the paintings and sculptures and prints and frescos of previous centuries, merit preservation, since they will be treasured continuingly and increasingly by scholars, connoisseurs, and thankful popular audiences of future generations - for the Botticellis and Rembrandts and Vermeers and Turners and Monets and Van Goghs of our era will be found among the experimental filmmakers. Experimental films pose many special problems that account for some of this neglect. Independent production often means that the "owner" of legal rights to the film may be in question, so the time and money spent on a restoration may be lost when a putative owner surfaces to claim the restored product. Because the style of an experimental film may be eccentric in the extreme, it can be hard to determine its original state: is this print complete? Have colors changed? was there a sound accompaniment? what was the speed or configuration of projection? etc. -

Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation)

MOMENT SOUND 75 Stewart Ave #424, Brooklyn NY, 11237 momentsound.com | 847.436.5585 | [email protected] Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation) a1 - Anything (Slava) a2 - Genie (Garo) a3 - Violence Jack (Lokua) a4 - Steamship (Garo) b1 - Chiberia (Lokua) b2 - Nightlife Reconsidered (Garo) b3 - Cosmic River (Slava) Scheduled for release on March 9th, 2010 The Moment Sound Vol. 1 compilation is the inauguration of the vinyl series of the Moment Sound label. It is comprised of original material by its founders Garo, Lokua and Slava. Swirling analog synths, dark pensive moods and intricate drum programming fill out the LP and at times evoke references to vintage Chicago house, 80's horror-synth, British dub and early electro. A soft, dreamlike atmosphere coupled with an understated intensity serves as the unifying character of the compilation. ….... Moment Sound is a multi-faceted label overseen by three musicians from Chicago – Joshua Kleckner, Garo Tokat and Slava Balasanov. All three share a fascination with and desire to uncover the essence of music – its primal building blocks. Minute details of old and new songs of various genres are sliced and dissected, their rhythmic and melodic elements carefully analyzed and cataloged to be recombined into a new, unpredictable yet classic sound. Performing live electronics together since early 2000s – anywhere from art galleries to grimy warehouse raves and various traditional music venues – they have proven to be an undeniable and highly versatile force in the Chicago music scene. Moment Sound does not have a static "sound". Instead, the focus is on the aesthetic of innovation rooted in tradition – a meeting point of the past and the future – the sound of the moment. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses

SCMS 2011 MEDIA CITIZENSHIP • Conference Program and Screening Synopses The Ritz-Carlton, New Orleans • March 10–13, 2011 • SCMS 2011 Letter from the President Welcome to New Orleans and the fabulous Ritz-Carlton Hotel! On behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to our members, professional staff, and volunteers who have put enormous time and energy into making this conference a reality. This is my final conference as SCMS President, a position I have held for the past four years. Prior to my presidency, I served two years as President-Elect, and before that, three years as Treasurer. As I look forward to my new role as Past-President, I have begun to reflect on my near decade-long involvement with the administration of the Society. Needless to say, these years have been challenging, inspiring, and expansive. We have traveled to and met in numerous cities, including Atlanta, London, Minneapolis, Vancouver, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. We celebrated our 50th anniversary as a scholarly association. We planned but unfortunately were unable to hold our 2009 conference at Josai University in Tokyo. We mourned the untimely death of our colleague and President-Elect Anne Friedberg while honoring her distinguished contributions to our field. We planned, developed, and launched our new website and have undertaken an ambitious and wide-ranging strategic planning process so as to better position SCMS to serve its members and our discipline today and in the future. At one of our first strategic planning sessions, Justin Wyatt, our gifted and hardworking consultant, asked me to explain to the Board why I had become involved with the work of the Society in the first place. -

“War of the Worlds Special!” Summer 2011

“WAR OF THE WORLDS SPECIAL!” SUMMER 2011 ® WPS36587 WORLD'S FOREMOST ADULT ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 25, 2011 SUMMER 2011 $6.95 HM0811_C001.indd 1 5/3/11 2:38 PM www.wotw-goliath.com © 2011 Tripod Entertainment Sdn Bhd. All rights reserved. HM0811_C004_WotW.indd 4 4/29/11 11:04 AM 08/11 HM0811_C002-P001_Zenescope-Ad.indd 3 4/29/11 10:56 AM war of the worlds special summER 2011 VOlumE 35 • nO. 5 COVER BY studiO ClimB 5 Gallery on War of the Worlds 9 st. PEtERsBuRg stORY: JOE PEaRsOn, sCRiPt: daVid aBRamOWitz & gaVin YaP, lEttERing: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, aRt: PuPPEtEER lEE 25 lEgaCY WRitER: Chi-REn ChOOng, aRt: WankOk lEOng 59 diVinE Wind aRt BY kROmOsOmlaB, COlOR BY maYalOCa, WRittEn BY lEOn tan 73 thE Oath WRitER: JOE PEaRsOn, aRtist: Oh Wang Jing, lEttERER: ChEng ChEE siOng, COlORist: POPia 100 thE PatiEnt WRitER: gaVin YaP, aRt: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, COlORs: ammaR "gECkO" Jamal 113 thE CaPtain sCRiPt: na'a muRad & gaVin YaP, aRt: slaium 9. st. PEtERsBuRg publisher & editor-in-chief warehouse manager kEVin Eastman JOhn maRtin vice president/executive director web development hOWaRd JuROFskY Right anglE, inC. managing editor translators dEBRa YanOVER miguEl guERRa, designers miChaEl giORdani, andRiJ BORYs assOCiatEs & JaCinthE lEClERC customer service manager website FiOna RussEll WWW.hEaVYmEtal.COm 413-527-7481 advertising assistant to the publisher hEaVY mEtal PamEla aRVanEtEs (516) 594-2130 Heavy Metal is published nine times per year by Metal Mammoth, Inc. Retailer Display Allowances: A retailer display allowance is authorized to all retailers with an existing Heavy Metal Authorization agreement. -

A Paródia Do Drama Shakespeariano Como Evolução Das Histórias Em Quadrinhos

LEONARDO VINICIUS MACEDO PEREIRA AI DE TI, YORICK BROWN: A PARÓDIA DO DRAMA SHAKESPEARIANO COMO EVOLUÇÃO DAS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. VIÇOSA MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL 2015 Ficha catalográfica preparada pela Biblioteca Central da Universidade Federal de Viçosa - Câmpus Viçosa T Pereira, Leonardo Vinícius Macedo, 1981- P434a Ai de ti, Yorick Brown : a paródia do drama shakespeariano 2015 como evolução das histórias em quadrinhos / Leonardo Vinícius Macedo Pereira. – Viçosa, MG, 2015. viii, 124f. : il. (algumas color.) ; 29 cm. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Sirlei Santos Dudalski. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Referências bibliográficas: f.105-115. 1. Literatura comparada. 2. Literatura - Adaptação. 3. Histórias em quadrinhos. 4. Paródia. 5. Shakespeare, William,1564-1616 . I. Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Departamento de Letras. Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras. II. Título. CDD 22. ed. 809 LEONARDO VINICIUS MACEDO PEREIRA AI DE TI, YORICK BROWN: A PARÓDIA DO DRAMA SHAKESPEARIANO COMO EVOLUÇÃO DAS HISTÓRIAS EM QUADRINHOS Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. APROVADA: 13 de março de 2015. __________________________ __________________________ Fulvio Torres Flores Nilson Adauto Guimarães da Silva ____________________________ -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation

DOCTORAL THESIS Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation Reynolds, Loni Sophia Award date: 2011 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation by Loni Sophia Reynolds BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing University of Roehampton 2011 Reynolds i ABSTRACT My thesis explores the role of religion and spirituality in the work of the Beat Generation, a mid-twentieth century American literary movement. I focus on four major Beat authors: William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso. Through a close reading of their work, I identify the major religious and spiritual attitudes that shape their texts. All four authors’ religious and spiritual beliefs form a challenge to the Modern Western worldview of rationality, embracing systems of belief which allow for experiences that cannot be empirically explained. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

Survival Research Laboratories: a Dystopian Industrial Performance Art

arts Article Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art Nicolas Ballet ED441 Histoire de l’art, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Galerie Colbert, 2 rue Vivienne, 75002 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 29 January 2019 Abstract: This paper examines the leading role played by the American mechanical performance group Survival Research Laboratories (SRL) within the field of machine art during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and as organized under the headings of (a) destruction/survival; (b) the cyborg as a symbol of human/machine interpenetration; and (c) biomechanical sexuality. As a manifestation of the era’s “industrial” culture, moreover, the work of SRL artists Mark Pauline and Eric Werner was often conceived in collaboration with industrial musicians like Monte Cazazza and Graeme Revell, and all of whom shared a common interest in the same influences. One such influence was the novel Crash by English author J. G. Ballard, and which in turn revealed the ultimate direction in which all of these artists sensed society to be heading: towards a world in which sex itself has fallen under the mechanical demiurge. Keywords: biomechanical sexuality; contemporary art; destruction art; industrial music; industrial culture; J. G. Ballard; machine art; mechanical performance; Survival Research Laboratories; SRL 1. Introduction If the apparent excesses of Dada have now been recognized as a life-affirming response to the horrors of the First World War, it should never be forgotten that society of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s was laboring under another ominous shadow, and one that was profoundly technological in nature: the threat of nuclear annihilation. -

Monte Cazazzas Reputation Ist Böse, Berüchtigt Und Mysteriös

Foto: Rokko Monte Cazazzas Reputation ist böse, berüchtigt und mysteriös. Um ihn ranken sich Geschehnisse, die niemand zu bestätigen vermag. Die Interviews, die er seit den 1970ern gegeben hat, lassen sich an einer Hand abzählen. Hier eines davon: DER VIRUS MONTE CAZAZZA Text: Rokko 4 5 aber es gab wiederholtermaßen disziplinäre Probleme mit Musikschaffen ist so zurückhaltend wie vielfältig: von rohen Cazazza, der Schulstufen übersprungen hatte, die High Industrial-Perlen, verschmitzt schaurigem Zeug für Hor- School mit 15 beendete und dann sofort in die Bay Area rorfilme (»Tiny Tears«), Burroughs-beeinflussten Cut-Ups zog. »Ich kaufte mir ein Flugticket und flog so weit weg, (»Kick That Habit Man«), dystopischen Rap-Hits (»A is for wie ich es mir leisten konnte. Wenn ich genug Geld ge- Atom«) und Zusammenarbeiten mit Künstlern wie Factrix, habt hätte, wäre ich wahrscheinlich nach Tasmanien oder Psychic TV und Leather Nun (extrem geiler Schleicher: irgendwohin noch viel weiter weg geflogen, aber ich hatte »Slow Death«) gilt es in dem schmalen Ouevre verhältnis- damals auch keinen Pass und hätte die USA nicht verlassen mäßig unglaublich viel zu entdecken. Ein obskures Musik- können.« Ob er irgendwelche Freunde an der Westküste stück trägt den Titel »Distress«: dabei hört man Schüsse, gehabt hätte? »Keine einzige Seele. Am Anfang hab ich eine jemandem schreien »Are you ready for the real thing?« und zeitlang am Flughafen in San Francisco gewohnt. Damals daraufhin einnehmendes Weinen, während Cazazza recht war das noch nicht so streng und ich lernte bald die Haus- fröhlich dazu singt. Ob er die Zutaten dieses Schauermär- meister und Angestellten kennen.