Quebec Song: Strategies in the Cultural Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Song and Nationalism in Quebec

Song and Nationalism in Quebec [originally published in Contemporary French Civilization, Volume XXIV, No. 1, Spring /Summer 2000] The québécois national mythology is dependent on oral culture for sustenance. This orality, while allowing a popular transmission of central concepts, also leaves the foundations of a national francophone culture exposed to influence by the anglophone forces that dominate world popular culture. A primary example is song, which has been linked to a nationalist impulse in Quebec for over thirty years. What remains of that linkage today? Economic, cultural, political and linguistic pressures have made the role of song as an ethnic and national unifier increasingly ambiguous, and reflect uncertainties about the Quebec national project itself, as the Quebec economy becomes reflective of global trends toward supranational control. A discussion of nationalism must be based on a shared understanding of the term. Anthony Smith distinguishes between territorial and ethnic definitions: territorially defined nations can point to a specific territory and rule by law; ethnies, on the other hand, add a collective name, a myth of descent, a shared history, a distinctive culture and a sense of solidarity to the territorial foundation. If any element among these is missing, it must be invented. This “invention” should not be seen as a negative or devious attempt to distort the present or the past; it is part of the necessary constitution of a “story” which can become the foundation for a national myth-structure. As Smith notes: "What matters[...] is not the authenticity of the historical record, much less any attempt at 'objective' methods of historicizing, but the poetic, didactic and integrative purposes which that record is felt to disclose" (25). -

MUS LISTE CHANSONS-9 Juillet P1

MUSIQUE Le Québec de Charlebois à Arcade Fire MUSIC Quebec: From Charlebois to Arcade Fire Crédits partiels des chansons et des productions audiovisuelles Partial credits for songs and audiovisual productions L’INSOLENCE DE LA JEUNESSE Welcome Soleil, Jim et Bertrand, © 1976 INSOLENCE OF YOUTH (Bertrand Gosselin) Comme un fou, Harmonium, © 1976 Le Ya Ya, Joël Denis, © 1965 (Serge Fiori, Michel Normandeau) (Morris Levy, Clarence Lewis, adaptation française / french La maudite machine, Octobre, © 1973 adaptation: Joël Denis) (Pierre Flynn) Le p’tit popy, Michel Pagliaro (Les Chanceliers), © 1967 La bourse ou la vie, Contraction, © 1974 (Lindon Oldham, Dan Penn) (Georges-Hébert Germain, Robert Lachapelle, Yves Laferrière, Tu veux revenir, Gerry Boulet (Les Gants blancs), © 1967 Christiane Robichaud) (Robert Feldman, Gerald Goldstein, Richard Gottehrer) Les saigneurs, Opus 5, © 1976 Tout peut recommencer, Ginette Reno, © 1963 (Luc Gauthier) (Jerry Reed) Beau Bummage, Aut’chose, © 1976 Ces bottes sont faites pour marcher, Dominique Michel, © 1966 (Jacques Racine, Jean-François St-Georges, Lucien Francoeur) (Lee Hazlewood) Dear Music, Mahogany Rush, © 1974 (Frank Marino) Yéyé partout, Jenny Rock, Jeunesse Oblige (Radio-Canada), Ma patrie est à terre, Offenbach, © 1975 1967 (Roger Belval, Gérald Boulet, Jean Gravel, Pierre Harel, Michel Ton amour a changé ma vie, Les Classels, Copain Copain Lamothe) , Plume Latraverse, © 1978 (Radio-Canada), 1964 Le rock and roll du grand flanc mou (Michel Latraverse) , 20 ans Express (Radio- Le short trop court interdit à Verdun Closer Together, The Box, © 1987 Canada), 27 juillet 1963 / July 27, 1963 (Guy Pisapia, Jean-Pierre Brie, Luc Papineau, Jean Marc Pisapia) Cash City, Luc De Larochellière, © 1990 RÊVER DE MONDES DIFFÉRENTS (Luc De Larochellière, Marc Pérusse) DREAMING OF OTHER WORLDS Les Yankees, Richard Desjardins, © 1992 (Richard Desjardins) J’ai souvenir encore, Claude Dubois, © 1964 Modern Man, Arcade Fire, © 2010 (Claude Dubois) (Edwin F. -

Cahier-Chansons.Pdf

Chansons Hugo Villeneuve Janvier 2006 Contents 1 Aznavour, Charles 1 Emmenez-moi . 2 Labohème ........................................... 4 2 Beau Dommage 5 23 Décembre . 6 Harmonie du Soir à Châteauguay . 7 Hockey.............................................. 8 La Complainte du Phoque en Alaska . 9 Le blues de la métropole . 10 Le Picbois . 11 Montréal . 12 3 Beatles, The 15 Norwegian Wood . 16 That’s Alright Mama . 17 TwoOfUs............................................ 18 4 Brassens, Georges 19 Les copains d’abord . 20 Les Trompettes de la Renommée . 22 Les Trompettes de la Renommée . 24 Le parapluie . 26 5 Cabrel, Francis 27 Elle écoute pousser les fleurs . 28 6 Cash, Johnny 29 I Walk The Line . 30 He Turned The Water Into Wine . 31 Jackson . 32 Folsom Prison Blues . 34 WantedMan .......................................... 35 I Still Miss Someone . 36 San Quentin . 37 City of New Orleans . 38 City of New Orleans . 40 A Boy Named Sue . 42 iii Big River . 44 The Wreck of Old 97 . 45 7 Cohen, Leonard 47 So Long, Marianne . 48 8 Corcoran, Jim 51 D’la bière au ciel . 52 9 Dassin, Joe 55 Salut les amoureux . 56 10 Desjardins, Richard 57 ...et j’ai couché dans mon char . 58 Lebongars ........................................... 60 11 Dubois, Claude 63 Comme tu voudras . 64 Comme un million de gens . 65 Femmes de rêve . 66 J’ai souvenir encore . 67 Le blues du businessman . 68 12 Ferland, Jean-Pierre 69 Je reviens chez nous . 70 13 Guess Who, The 71 Hand Me Down World . 72 Share the Land . 74 These eyes . 76 14 Jazz 77 Fever............................................... 78 The girl from Ipanema . 79 15 Jim et Bertrand 81 Welcome Soleil . -

Alain Simard

Alain Simard Chairman of the Board of L'Équipe Spectra, FrancoFolies de Montréal and Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, and Founding President Emeritus de MONTRÉAL EN LUMIÈRE Founder of three festivals One of the pioneers and leaders of the Canadian music industry, Alain Simard has been a builder of Quebec's culture for nearly 50 years. His passionate work as a manager, agent, concert and festival promoter, recording and television producer as well as avenue owner has contributed to the development and professionalization of our cultural industry and has generated extraordinary artistic, social, economic and touristic benefits for Montreal and Canada. The trail-blazing promoter When he was 18 years old, he opened a live concert café, La Clef, and organized pop festivals featuring the first Montreal underground bands, some of which he managed. From 1971, with Kosmos productions, he was the first to promote British groups Genesis, Gentle Giant, Pink Floyd and Procol Harum in Eastern Canada and initiated the midnight shows in Cinéma Outremont with several international artists. In 1977, he organized Harmonium’s L’Heptade only arena tour and founded Spectra Scène (which would become L’Équipe Spectra in 1992) with André Ménard and Denyse McCann. Together, they launched the Cinéma Saint-Denis as a venue, followed by El Casino club and soon the legendary Spectrum de Montréal in 1983. Alain Simard and Spectra were also behind the transformation of the Métropolis (formerly a nightclub) into a venue in 1997, the renovation and reopening of the Théâtre Outremont in 2001 and the creation of the L’Astral concert club in the seven-storey Maison du Festival de Jazz. -

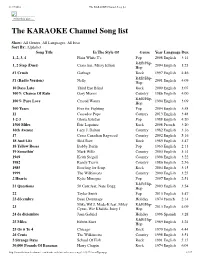

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Apprendrelaguitare.Ca "Chansons Disponibles Uniquement Pour Les Gens Qui Suivent Les Cours En Privés Ou Sur Webcam"

Apprendrelaguitare.ca "chansons disponibles uniquement pour les gens qui suivent les cours en privés ou sur webcam" Artistes Titre Source ? American Jesus Tab ? Blues Enc ? Cruel To Be Kind Tab ? Feelings Enc ? J'ai Mal Doc ? La Danse D'helene Doc ? Lili Marleen Doc ? Mon Seul Amour ( Les Enchainees ) Doc ? Non Ne Me Quitte Pas Doc ? Oui Devant Dieu Je Promets Doc ? Quando Quando Enc ? Québecois Part ? Rebel Rouser Enc ? Reflet De Ma Vie Doc ? Unchained Melody Enc ? Vivre Sans Toi Doc 10 Years Through The Iris rv157 10 Years Wasteland rv148 3 Doors Down Be Like That doc 3 Doors Down Be Like That Rv58 3 Doors Down Here Without You Rv91 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Rv47 3 Doors Down Loser Rv49 311 All Mixed Up Rv33 311 You Wouldn't Believe Rv58 A Perfect Circle Judith Rv47 Ac/Dc Back In Black Tab Ac/Dc Back in Black rv114 Ac/Dc Big Gun Rv04 Ac/Dc Can't Stop Rock'n'roll Tab Ac/Dc For Those about To Rock rv174 Ac/Dc Girls Got Rhythm rv170 Ac/Dc Have A Drink On Me Rv22 Ac/Dc Have a Drink On Me rv140 Ac/Dc Hell's Bells Rv42 Ac/Dc Hell's Bells Rv103 Ac/Dc Hell's Bells(Solo) Rv43 Ac/Dc Highway To Hell Rv78 Ac/Dc Let There Be Rock rv160 Ac/Dc Rock'n Roll Ain't Noise Polution Tab Ac/Dc Shoot To Thrill Rv68 Ac/Dc T.N.T rv181 Ac/Dc Thunderstruck Rv13 Ac/Dc TNT tab Ac/Dc Whole Lotta Rosie rv159 Ac/Dc You Shook Me All Night Long Rv57 Ac/Dc You Shook Me All Night Long Rv32 Ac/Dc You shook me all night long rv185 Accept Balls to the wall rv183 Adamo C'est Ma Vie Doc Adema Givin' In Rv60 Adema The Way You Like It Rv66 Aerosmith Amazing Rv18 Aerosmith Cryin' -

La Chanson Pour Mémoire Roger Chamberland

Document generated on 09/30/2021 8:19 p.m. Québec français La chanson pour mémoire Roger Chamberland L’errance en littérature Number 97, Spring 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/44324ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Publications Québec français ISSN 0316-2052 (print) 1923-5119 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Chamberland, R. (1995). Review of [La chanson pour mémoire]. Québec français, (97), 94–95. Tous droits réservés © Les Publications Québec français, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CHANSON Roger CHAMBERLAND La chanson pour mémoire Beau Dommage tif. Si la presse montréalaise a Rarement a-t-on vu un groupe ou un salué avec grand éclat cette interprète créer de telles attentes chez le soirée mémorable, force est public. Mais Beau Dommage, c'est Beau d'avouer que l'album double Dommage : un groupe clé de la décennie que l'on en a tiré, La Sympho 1970 qui, après seize ans d'absence, nie du Québec, consacre ces renoue avec la musique et son public. Si nouvel les i nterprétations et re- celui-ci a vieilli et ne porte plus nécessai nouvelle l'expérience du rement les cheveux longs, les jeans et les spectacleparla présence sou chemises amples, il n'en demeure pas tenue du public. -

Canadian Recording Artists Artistes Canadiens De La Chanson

JULY-AUGUST 2013 JUILLET-AOÛT 2013 VOLUME XXII NO 3 Canadian Recording Artists See page 8 Artistes canadiens de la chanson Voir à la page 8 Available July 19 Offertes dès le 19 juillet A) Canadian Recording Artists (Rush) / B) Canadian Recording Artists (The Tragically Hip) / Artistes canadiens de la chanson (Rush) Artistes canadiens de la chanson (The Tragically Hip) 15” x 20” / 381 mm x 508 mm 341960 $ 8995 a 15” x 20” / 381 mm x 508 mm 341961 $ 8995 a Portraits of current band members Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee and This limited edition framed print showcases an enlargement of the Neil Peart are highlighted on this limited edition framed print. / Cette stamp art, which features all five members of the band. / Cette reproduction encadrée, à tirage limité, se compose de photos des reproduction encadrée, à tirage limité, se compose d’un agrandissement membres actuels du groupe − Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee et Neil Peart. de la figurine à l’effigie des cinq membres de ce groupe. C) Canadian Recording Artists (The Guess Who) / D) Canadian Recording Artists (Beau Dommage) / Artistes canadiens de la chanson (The Guess Who) Artistes canadiens de la chanson (Beau Dommage) 15” x 20” / 381 mm x 508 mm 341962 $ 8995 a 15” x 20” / 381 mm x 508 mm 341963 $ 8995 a Featuring historical portraits of The Guess Who, this limited edition Recognizing the success and contributions of Beau Dommage, this framed print includes six mint commemorative stamps emblazoned limited edition framed print includes six mint commemorative stamps with the legendary logo of the celebrated band. -

Liste Par Titres

apprendrelaguitare.ca "chansons disponibles uniquement pour les gens qui suivent les cours en privés e sur webcam" Titre Artistes Source '39 Queen Rv82 'Round Midnight Wes Montgomery Rv119 1979 Smashing Pumpkins Rv28 19th nervous breakdown Rolling Stones rv185 2 Minutes to Midnight Iron Maiden rv137 23 Decembre Beau Dommage Doc 5 Minutes Alone Pantera Rv15 5 Minutes alone Pantera rv140 A Conspiracy Black Crowes Rv20 A Favour House Atlantic Coheed And Cambria Rv102 A Gunshot To The Head Of Trepidation Trivium rv148 A Hard Day's Night Beatles rv118 A Hard Day's Night Beatles Doc À L'enfant Que J'aurai Okoumé Doc A Little Help From My Friend Beatles Doc A Quitter Never Wins Jonny Lang Doc A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Rv85 A Toi Que Je Pense Les Sultans Doc A Tout Le Monde(Solo) Megadeth Rv43 A.D.I.D.A.S Korn Rv55 About A Girl Nirvana Doc Ace Of Spades Motorhead Rv29 Ace Of Spades Motorhead Rv80 Aces High Iron Maiden rv133 Achy Breaky Dance Stef Cars Doc Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Doc Acropolis Adieu Mireille Mathieu Doc Adam & Ève Kaïn doc Adam's Song Blink-182 Rv63 Addicted To That Rush Mr. Big Rv11 Adeste Fideles Xmas Enc Aerials System Of A Down rv128 Again Alice In Chains Rv32 Against The Wind Bob Seger Rv82 Ahead By A Century Tragically Hip Doc Ailleurs Marjo Doc Aime Bruno Pelletier Doc Aimer Mario Pelchat doc Ain't Comin' Home Silvertide rv118 Ain't talkin' bout love Van Halen tab Ainsi Soit-il Jean-François Brault part Airegin Wes Montgomery rv144 Alberta Eric Clapton Tab Alcohaulin' ass Hellyeah rv179 Alcohol Brad Paisley -

Music Guide Music HISTORY There Was a Time When “Elevator Music” Was All You Heard in a Store, Hotel, Or Other Business

Music Guide Music HisTORY There was a time when “elevator music” was all you heard in a store, hotel, or other business. Yawn. 1 1971: a group of music fanatics based out of seattle - known as Aei Music - pioneered the use of music in its original form, and from the original artists, inside of businesses. A new era was born where people could enjoy hearing the artists and songs they know and love in the places they shopped, ate, stayed, played, and worked. 1 1985: DMX Music began designing digital music channels to fit any music lover’s mood and delivered this via satellite to businesses and through cable TV systems. 1 2001: Aei and DMX Music merge to form what becomes DMX, inc. This new company is unrivaled in its music knowledge and design, licensing abilities, and service and delivery capability. 1 2005: DMX moves its home to Austin, TX, the “Live Music capital of the World.” 1 Today, our u.s. and international services reach over 100,000 businesses, 23 million+ residences, and over 200 million people every day. 1 DMX strives to inspire, motivate, intrigue, entertain and create an unforgettable experience for every person that interacts with you. Our mission is to provide you with Music rockstar service that leaves you 100% ecstatic. Music Design & Strategy To get the music right, DMX takes into account many variables including customer demographics, their general likes and dislikes, your business values, current pop culture and media trends, your overall décor and design, and more. Our Music Designers review hundreds of new releases every day to continue honing the right music experience for our clients. -

Caractéristiques Et Logiques Des Musiques Populaires

Caractéristiques et logiques des musiques populaires Par Suzanne Lemieux Thèse présentée pour répondre à l’une des exigences du doctorat en philosophie (Ph.D.) en sciences humaines École des études supérieures Université Laurentienne Sudbury, Ontario © Suzanne Lemieux, 2013 iii RÉSUMÉ L’objet de notre thèse de doctorat concerne les caractéristiques et les logiques des musiques populaires. D’une façon générale, nous nous demandons : quelles sont les logiques qui déterminent le thème de l’œuvre dans la musique populaire ? Quelles caractéristiques découlent de ces logiques ? Les ouvrages recensés ont été classés dans trois ensembles selon que les musiques populaires sont définies comme standard, comme standard et originales ou comme hétérogènes. La thèse veut vérifier laquelle de ces tendances (standard, standard/originale, hétérogène) explique le mieux l’œuvre de musique populaire. Pour y parvenir, la recherche d’une explication des œuvres de musique populaire a dû passer par une opérationnalisation et une vérification empirique des œuvres de musique populaire. Les hypothèses spécifiques liées aux thèses standard, standard/originale et hétérogène, ainsi qu’une hypothèse générale permettant une articulation entre ces trois thèses ont été soumises aux résultats de notre analyse qui a porté sur 110 chansons à succès canadiennes-françaises et françaises qui appartiennent à la période qui va de 1995 à 2005. Les résultats montrent que l’hypothèse des hétérogénistes est grandement confirmée. Cependant, nos analyses ont repéré des données marginales qui vont dans le sens des attentes des standardistes et des dualistes. Pour dépeindre l’ensemble des musiques populaires, nous proposons une nouvelle hypothèse hétérogène, inclusive de ces quelques représentations standard que nous avançons sous le concept de « tendance hétérogène ».