Linguistic Norm Vs. Functional Competence: Introducing Quebec French to American Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland a Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland A Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY PLANNING ORGANIZATION “A Forum for Communication and Discussion for a Vibrant Community” Home of the “North American Bigfoot Center” P. O. Box 363 Boring, Orygun 97009 Michael Fitz, Chair DAYTIME TELEPHONE: 503-502-5837 EMAIL: [email protected] www.boringcpo.org NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING 1 JUNE 2021 at 7:01 PM AT THE Boring Grange On SE Grange St MEETING AGENDA MEET AND GREET, AROUND 6:00 PM CHANGE TO THE MEETING: WE ARE STREAMING THE MEETING FROM OUR FACEBOOK PAGE. IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS ON STREAMING PLEASE DIRECT THEM TO STEVE BATES, YOU WILL GET WAY BETTER ANSWERS THAN ASKING ME. 1. Meeting called to order, flag salute self introductions and a little trivia, statistics on what the average citizen knows, by source. 2. Reports and advisements: A. Boring Water District B. Boring Oregon Foundation C. Boring-Damascus Grange D. Mt. Hood Center (Old Boring Equestrian Center) Liz Delmatoff the Learning Collective education administrator will have answers to your questions on the full time equestrian learning center and how it relates to the school system, charter schools and home schooling. 4. A moment of Boring History presented by Bruce Haney Bruce’s new book is out, on sale in several places around the county and I have read it. Well written and a very enjoyable read, I don’t know what he will have tonight but I know that it is never a boring minute. 5. Minutes of the previous meeting. 6. Treasurers report. 7. Land use issues: A. -

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Song and Nationalism in Quebec

Song and Nationalism in Quebec [originally published in Contemporary French Civilization, Volume XXIV, No. 1, Spring /Summer 2000] The québécois national mythology is dependent on oral culture for sustenance. This orality, while allowing a popular transmission of central concepts, also leaves the foundations of a national francophone culture exposed to influence by the anglophone forces that dominate world popular culture. A primary example is song, which has been linked to a nationalist impulse in Quebec for over thirty years. What remains of that linkage today? Economic, cultural, political and linguistic pressures have made the role of song as an ethnic and national unifier increasingly ambiguous, and reflect uncertainties about the Quebec national project itself, as the Quebec economy becomes reflective of global trends toward supranational control. A discussion of nationalism must be based on a shared understanding of the term. Anthony Smith distinguishes between territorial and ethnic definitions: territorially defined nations can point to a specific territory and rule by law; ethnies, on the other hand, add a collective name, a myth of descent, a shared history, a distinctive culture and a sense of solidarity to the territorial foundation. If any element among these is missing, it must be invented. This “invention” should not be seen as a negative or devious attempt to distort the present or the past; it is part of the necessary constitution of a “story” which can become the foundation for a national myth-structure. As Smith notes: "What matters[...] is not the authenticity of the historical record, much less any attempt at 'objective' methods of historicizing, but the poetic, didactic and integrative purposes which that record is felt to disclose" (25). -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

MUS LISTE CHANSONS-9 Juillet P1

MUSIQUE Le Québec de Charlebois à Arcade Fire MUSIC Quebec: From Charlebois to Arcade Fire Crédits partiels des chansons et des productions audiovisuelles Partial credits for songs and audiovisual productions L’INSOLENCE DE LA JEUNESSE Welcome Soleil, Jim et Bertrand, © 1976 INSOLENCE OF YOUTH (Bertrand Gosselin) Comme un fou, Harmonium, © 1976 Le Ya Ya, Joël Denis, © 1965 (Serge Fiori, Michel Normandeau) (Morris Levy, Clarence Lewis, adaptation française / french La maudite machine, Octobre, © 1973 adaptation: Joël Denis) (Pierre Flynn) Le p’tit popy, Michel Pagliaro (Les Chanceliers), © 1967 La bourse ou la vie, Contraction, © 1974 (Lindon Oldham, Dan Penn) (Georges-Hébert Germain, Robert Lachapelle, Yves Laferrière, Tu veux revenir, Gerry Boulet (Les Gants blancs), © 1967 Christiane Robichaud) (Robert Feldman, Gerald Goldstein, Richard Gottehrer) Les saigneurs, Opus 5, © 1976 Tout peut recommencer, Ginette Reno, © 1963 (Luc Gauthier) (Jerry Reed) Beau Bummage, Aut’chose, © 1976 Ces bottes sont faites pour marcher, Dominique Michel, © 1966 (Jacques Racine, Jean-François St-Georges, Lucien Francoeur) (Lee Hazlewood) Dear Music, Mahogany Rush, © 1974 (Frank Marino) Yéyé partout, Jenny Rock, Jeunesse Oblige (Radio-Canada), Ma patrie est à terre, Offenbach, © 1975 1967 (Roger Belval, Gérald Boulet, Jean Gravel, Pierre Harel, Michel Ton amour a changé ma vie, Les Classels, Copain Copain Lamothe) , Plume Latraverse, © 1978 (Radio-Canada), 1964 Le rock and roll du grand flanc mou (Michel Latraverse) , 20 ans Express (Radio- Le short trop court interdit à Verdun Closer Together, The Box, © 1987 Canada), 27 juillet 1963 / July 27, 1963 (Guy Pisapia, Jean-Pierre Brie, Luc Papineau, Jean Marc Pisapia) Cash City, Luc De Larochellière, © 1990 RÊVER DE MONDES DIFFÉRENTS (Luc De Larochellière, Marc Pérusse) DREAMING OF OTHER WORLDS Les Yankees, Richard Desjardins, © 1992 (Richard Desjardins) J’ai souvenir encore, Claude Dubois, © 1964 Modern Man, Arcade Fire, © 2010 (Claude Dubois) (Edwin F. -

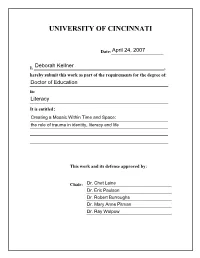

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Creating a Mosaic Within Time and Space: the role of trauma in identity, literacy, and life A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION In the Department of Literacy of the College of Education, Criminal Justice and Human Services Winter 2007 By DEBORAH KELLNER Committee Chair: Chet Laine, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation presents a qualitative, ethnographic, life history study of the link between trauma exposure and literacy habits of one female college developmental student. It is an investigation of the correlation between trauma-related symptoms, identity, literacy habits, and performance in all aspects of life. Furthermore, it is an analysis of the relationship of coping with trauma exposure to coping with schooling. In terms of trauma, this single case presents multiple and repetitive exposure to trauma and suggests that traumatic experiences emerge as part of a victim’s identity. Victimization is so overwhelming that the individual describes herself in the trauma experience rather than in some other way. Her symptoms closely align with the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and her trauma exposure results in massive chaos during her schooling years. In terms of literacy, this data suggests that this individual’s external literacy skills, her reading and writing, as well as her internal literacy skills, her interpretation of her world and her life, have a strong affiliation with trauma. -

Michael Arnold: All Right

Michael Arnold: All right. Welcome to episode three, Monday state of mind. My name is Michael Arnold. I am the director of alumni and recovery support services for the harmony foundation. On this episode, we are going to continue talking about the stories we tell ourselves. So if you're driving, you're just waking up. Maybe you're headed to the gym or out on that morning walk, or just getting your day going. You're going to want to make sure to have a pen and a piece of paper, or you're just going to have to put this episode on repeat because the guests that I have today, she's going to drop some serious knowledge bombs on the stories we tell ourselves. So do you guys want to know who this guest is? Her name is LauraBeth Burkhalter. LB. Do you want to tell everybody a little bit of, just give everybody a little bit of backstory about who you are, what you do? LB: Good morning guys. I'm LB. I am a person in recovery and I grew up in a little town called Natchez Mississippi. I'm currently the Director of. Community Engagement for Jade Recovery in Lakewood, Colorado. And I'm super stoked that Michael asked me to be on this podcast today because if there's one thing I know about it's stories and what I used to tell myself, Michael Arnold: Right. You know, that's, I was really excited to be able to start this podcast series out. -

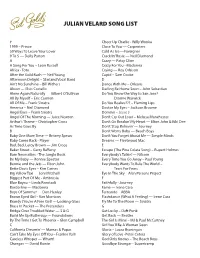

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Cahier-Chansons.Pdf

Chansons Hugo Villeneuve Janvier 2006 Contents 1 Aznavour, Charles 1 Emmenez-moi . 2 Labohème ........................................... 4 2 Beau Dommage 5 23 Décembre . 6 Harmonie du Soir à Châteauguay . 7 Hockey.............................................. 8 La Complainte du Phoque en Alaska . 9 Le blues de la métropole . 10 Le Picbois . 11 Montréal . 12 3 Beatles, The 15 Norwegian Wood . 16 That’s Alright Mama . 17 TwoOfUs............................................ 18 4 Brassens, Georges 19 Les copains d’abord . 20 Les Trompettes de la Renommée . 22 Les Trompettes de la Renommée . 24 Le parapluie . 26 5 Cabrel, Francis 27 Elle écoute pousser les fleurs . 28 6 Cash, Johnny 29 I Walk The Line . 30 He Turned The Water Into Wine . 31 Jackson . 32 Folsom Prison Blues . 34 WantedMan .......................................... 35 I Still Miss Someone . 36 San Quentin . 37 City of New Orleans . 38 City of New Orleans . 40 A Boy Named Sue . 42 iii Big River . 44 The Wreck of Old 97 . 45 7 Cohen, Leonard 47 So Long, Marianne . 48 8 Corcoran, Jim 51 D’la bière au ciel . 52 9 Dassin, Joe 55 Salut les amoureux . 56 10 Desjardins, Richard 57 ...et j’ai couché dans mon char . 58 Lebongars ........................................... 60 11 Dubois, Claude 63 Comme tu voudras . 64 Comme un million de gens . 65 Femmes de rêve . 66 J’ai souvenir encore . 67 Le blues du businessman . 68 12 Ferland, Jean-Pierre 69 Je reviens chez nous . 70 13 Guess Who, The 71 Hand Me Down World . 72 Share the Land . 74 These eyes . 76 14 Jazz 77 Fever............................................... 78 The girl from Ipanema . 79 15 Jim et Bertrand 81 Welcome Soleil . -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Real Stories of East LA L.A

Real Stories of East LA L.A. Poet Laureate Holding Out Winner of FRANCO AGUILAR LUIS J. RODRIGUEZ for Lady Luck by 6-Word-Story looks for ghosts on police brutality JOSEPH MATTSON contest in southern Mexico Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 Poetry Editors Gustavo Mateo, Nils Rabe Fiction Editors Joshua Inglada, Daniel Sosa Layout Board Alena Morales, Marcille Sanguino Business Manager Kevin Rocha Proofreader Extraordinaire Joshua Castro Staff Joanna Alvarado, Lucy Alvarez, Joshua Castro, Joshua Inglada, Gustavo Mateo, Alena Morales, Robert Perez, Nils Rabe, Kevin Rocha, Marcille Sanguino, Daniel Sosa Faculty Editor Dustin Lehren Concept Design Diana Chang Layout and Design Production Yegor Hovakimian Milestone Committee Joan Goldsmith Gurfield, Dolores Carlos, Alexis Solis, Susan Suntree Cover Art Front cover: Photograph Franco Aguilar, What Lies There (Hacienda Photo Essay) Back cover: Oil on printed photograph Franco Aguilar & Jesus Barrales, Out of the Smoke Inside cover: Digital Photograph Jemima Wyman, Sample from fabric archive Milestone is published annually by the East Los Angeles College English Department, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park, California 91754. U.S. Submission Guidelines: The editors invite digital submissions of poetry, fiction/non-fiction, comics, essays of literary interest, art, and photography. Guidelines at milestone.submittable.com 2 Contents Introduction . 5 Acknowledgments . 7 Amarillas | Joseph Hernandez . 8 This, My Father Talk- | Andrew Liu . 13 From The Municipal Gardens | Andrew Liu . 14 Sea Layers | Joshua Inglada . 16 My Main Conflict | Michael Guerra . 17 a + d + d + i + n + g | Joshua Castro . 18 #collegestudentproblems | Raul Meza . -

Alain Simard

Alain Simard Chairman of the Board of L'Équipe Spectra, FrancoFolies de Montréal and Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, and Founding President Emeritus de MONTRÉAL EN LUMIÈRE Founder of three festivals One of the pioneers and leaders of the Canadian music industry, Alain Simard has been a builder of Quebec's culture for nearly 50 years. His passionate work as a manager, agent, concert and festival promoter, recording and television producer as well as avenue owner has contributed to the development and professionalization of our cultural industry and has generated extraordinary artistic, social, economic and touristic benefits for Montreal and Canada. The trail-blazing promoter When he was 18 years old, he opened a live concert café, La Clef, and organized pop festivals featuring the first Montreal underground bands, some of which he managed. From 1971, with Kosmos productions, he was the first to promote British groups Genesis, Gentle Giant, Pink Floyd and Procol Harum in Eastern Canada and initiated the midnight shows in Cinéma Outremont with several international artists. In 1977, he organized Harmonium’s L’Heptade only arena tour and founded Spectra Scène (which would become L’Équipe Spectra in 1992) with André Ménard and Denyse McCann. Together, they launched the Cinéma Saint-Denis as a venue, followed by El Casino club and soon the legendary Spectrum de Montréal in 1983. Alain Simard and Spectra were also behind the transformation of the Métropolis (formerly a nightclub) into a venue in 1997, the renovation and reopening of the Théâtre Outremont in 2001 and the creation of the L’Astral concert club in the seven-storey Maison du Festival de Jazz.