Ivan Turgenev and His Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

Liberal Catholicism in France, 1845-1670 Dissertation

LIBERAL CATHOLICISM IN FRANCE, 1845-1670 DISSERTATION Presented Is fbrtial Ftalfillaent of the Requlreaents for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By JOHN KEITH HUOKABY, A. £., M. A, ****** The Ohio State University 1957 Approved by: CONTENTS Chapter Page I INTRODUCTION......................... 1 The Beginnings of Liberal Catholicism in F r a n c e ....................... 5 The Seoond Liberal Catholic Movement . 9 Issues Involved in the Catholic-Liberal Rapprochement . • ......... > . 17 I. The Challenge of Anticierlealism. • 17 II. Ohuroh-State Relatione........ 22 III.Political Liberalism and Liberal Catholic la n .................. 26 IV. Eeoncttlc Liberalism and Liberal Catholiciam ..... ........... 55 Scope and Nature of S t u d y .......... 46 II THE CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE UNIVERSITS.... 55 Lamennais vs. the Unlveralte........ 6l Oniv era it a under the July Monarchy. 66 Catholic and Unlversite Extremism .... 75 The Liberal Catholio Campaign ......... 61 III CHURCH-STATE RELATIONS................ 116 Traditional Attitudes ................. 117 The Program of L*Avaiilr........... 122 The Montalembert Formula* Mutual Independence but not Separation .... 129 Freedom of Conscience and Religion . 155 Syllabus of Errors ........... 165 17 GALL ICANISM AND ULTRAMONTANISM........... 177 Ultramontanism: de Maistre and Lamennais 160 The Second Liberal Catholic Movement. 165 The Vatican Council............. 202 V PAPAL SOVEREIGNTY AND ITALIAN UNITY. .... 222 71 POLITICAL OUTLOOK OF LIBERAL CATHOLICS . 249 Democracy and Political Equality .... 257 ii The Revolution of 1848 and Napoleon . 275 Quarantiem and Ant 1-etatlaae.............. 291 VII CONCLUSIONS.............................. 510 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY............................ 525 ill Chapter X INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the French Revolution the Roman Catholic Church placed itself in opposition to the dynamic historical forces in nineteenth-century France. -

13273 PSA Conf Programme 2011 PRINT

Transforming Politics: New Synergies 61st Annual International Conference 18 – 21 April 2011 Novotel London West, London, UK PSA 61st Annual International Conference London, 18 –21 April 2011 www.psa.ac.uk/2011 A Word of Welcome Dear Conference delegate You are extremely welcome to this 61st Conference of the Political Studies Association, held in the UK capital. The recently refurbished Hammersmith Novotel hotel offers high quality conference facilities all under one roof. We are expecting well over 500 delegates, representing over 50 different countries. There are more than 190 panels, as well as the workshops on Monday, building on last year’s innovation, and as a new addition, dedicated posters sessions. There are also three receptions. The Conference theme is ‘Transforming Politics: New Synergies’. Keynote speakers include Professor Carole Pateman, President of APSA, revisiting the concept of participatory democracy and Professor Iain McLean giving the Government and Opposition-sponsored Leonard Schapiro lecture on the subject of coalition and minority government. On Wednesday, our after-dinner speaker is Professor Tony Wright, (UCL and Birkbeck College) former MP and Chair of the Public Administration Select Committee. Amongst other highlights, Professor Vicente Palermo will discuss Anglo-Argentine relations and John Denham MP will talk on ‘English questions’ and the Labour Party’ and Sir Michael Aaronson, former Director General of Save the Children, will be drawing on his experience working in crisis situations to reflect on whether we had a choice in Libya today. Despite the worsening economic and policy environment, this has been a particularly active and successful year for the Association. Overall membership figures, including those for the new Teachers’ Section, continue to rise. -

The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature

Hamren 1 The Eternal Stranger: The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Kelly Hamren 4 May 2011 Hamren 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English Dr. Carl Curtis ____________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Emily Heady ____________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Thomas Metallo ____________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Hamren 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who have seen me through this project and, through support for my academic endeavors, have made it possible for me to come this far: to Dr. Carl Curtis, for his insight into Russian literature in general and Dostoevsky in particular; to Dr. Emily Heady, for always pushing me to think more deeply about things than I ever thought I could; to Dr. Thomas Metallo, for his enthusiastic support and wisdom in sharing scholarly resources; to my husband Jarl, for endless patience and sacrifices through two long years of graduate school; to the family and friends who never stopped encouraging me to persevere—David and Kathy Hicks, Karrie Faidley, Jennifer Hughes, Jessica Shallenberger, and Ramona Myers. Hamren 4 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chapter 2: Epiphany and Alienation...................................……………………………………...26 Chapter 3: “Yes—Feeling Early Cooled within Him”……………………………..……………42 Chapter 4: A Soul not Dead but Dying…………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 5: Where There’s a Will………………………………………………………………...96 Chapter 6: Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..130 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….134 Hamren 5 Introduction The superfluous man is one of the most important developments in the Golden Age of Russian literature—the period beginning in the 1820s and climaxing in the great novels of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. -

Prelims May 2007.Qxd

BOOK REVIEWS INGRID REMBOLD, Conquest and Christianization: Saxony and the Caro lingian World, 772–888 , Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, Fourth Series, 108 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), xviii +277 pp. ISBN 978 1 107 19621 6. £75.00 This book is based on the author’s Cambridge Ph.D. thesis, which was supervised by Rosamond McKitterick and submitted in 2014. The author, Ingrid Rembold, is now a Junior Research Fellow at Hertford College, Oxford, but following her Ph.D. submission, she obtained postdoctoral funding from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) to carry out research at the Georg August Uni - versity, Göttingen. It is important to mention this because it is clear that Rembold’s work has benefited immensely from her postdoctor - al studies; in contrast with other English publications in the field, her book shows not only an awareness but a profound and critical grasp of relevant research published in German, with which she is fully up to date. The bibliography alone (pp. 245–73) is ample proof of the author’s intensive engagement with the literature, as are her thor - ough footnotes, which number nearly a thousand. Indeed, sometimes one can have too much of a good thing; this reviewer feels that it was not really necessary, for example, for the author to list so many of Hedwig Röckelein’s publications in footnote 123, only to repeat them all again in the bibliography (pp. 268–9). The author correctly notes at the beginning of the study that ‘Sax - ony represents an important test case for the nature of Christian - ization and Christian reform in the early medieval world’ (p. -

The Liberal Illusion

The Liberal Illusion By LOUIS VEUILLOT (1866) Translated by RT. REV. MSGR. GEORGE BARRY O’TOOLE, PH. D., S. T. D. Professor of Philosophy in The Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C. With Biographical Foreword by REV. IGNATIUS KELLY, S. T. D., Professor of Romance Languages in De Sales College, Toledo, Ohio Of old time thou hast broken my yoke, thou hast burst my bands, and thou saidst: I will not serve. — Jer. 2:20. BIOGRAPHICAL FOREWORD PALADIN, and not a mere fighter,” says Paul Claudel of Louis A Veuillot. “He fought, not for the pleasure of fighting, but in defense of a holy cause, that of the Holy City and the Temple of God.” It is just one hundred years ago, 1838, that Louis Veuillot first dedicated himself to this holy cause. “I was at Rome,” he wrote as an old man recalling that dedication. “At the parting of a road, I met God. He beckoned to me, and as I hesitated to follow, He took me by the hand and I was saved. There was nothing else; no sermons, no miracles, no learned debates. A few recollections of my unlettered father, of my untutored mother, of my brother and little sisters.” This was Louis Veuillot’s conversion, the beginning of his apostolate of the pen which was to merit him the title of “Lay Father of the Church” from Leo XIII; “Model of them who fight for sacred causes” from Pius X; and from Jules Le Maitre the epithet “le grand catholique.” In the days of the Revolution, the maternal grandmother of Veuillot, Marianne Adam, a hatchet in her hand, had defended the cross of the church of Boynes in old Gatinais. -

King-Salter2020.Pdf (1.693Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Dostoevsky’s Storm and Stress Notes from Underground and the Psychological Foundations of Utopia John Luke King-Salter PhD Comparative Literature University of Edinburgh 2019 Lay Summary The goal of this dissertation is to combine philosophical and literary scholarship to arrive at a new interpretation of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. In this novel, Dostoevsky argues against the Russian socialists of the early 1860s, and attacks their ideal of a socialist utopia in particular. Dostoevsky’s argument is obscure and difficult to understand, but it seems to depend upon the way he understands the interaction between psychology and politics, or, in other words, the way in which he thinks the health of a society depends upon the psychological health of its members. It is usually thought that Dostoevsky’s problem with socialism is that it curtails individual liber- ties to an unacceptable degree, and that the citizens of a socialist utopia would be frustrated by the lack of freedom. -

The Story of the Nation's

' THE STO RY O F TH E NATIO NS. r c mum 800 Cla/h [Hm/mud 68. La g C , , , ' 73: Volume: are aimbe}! in [I nfol/mmng Special B indings ' al Pfru an ( Io/lo ill to F u m 110 exlra ” l , g p ll y, 1/ , r 0 d s Tree ( al ill d s o d ol ma /1a! e ge f. g e ge , g l r l imidc u ilt MM . , f ll g x P G NI IA. l w 8. H O f. B O 8 01112 . Anrnuu G u u G . 1 . By , By Pro R W LINSO N. MA . A m “W S. B f. K. 1 . MEDI A. ZBNMDB . 9 . y Pro J 9 By A R GO ZIN. Ma nn . A exa m . Rev . S. 2 0. TH E H ANSA T WNS. 3. B O By — i “A . H B LB N Z IMNERN. B agu o 000m . f. A un t) n EARL Y R T . By Pro . B I AIN By Prof R A LF ED J . CH URCH . TH E R Y . as. BAR BA COR SAIR S STA NLEY N - O O By LA E P LE. U 2 . R SS . W . By 3 IA By R . MO R y Prot mws UNDER TH E W . Do u R OM ANS. By vc xs Amm Mo nmso n. Prof. C T ND . O H N M AC 2 5 . S O LA By J xmro su LL D. an a n o ue. -

By Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Упырь by Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy. Russian poet and playwright (b. 24 August/5 September 1817 in Saint Petersburg; d. 28 September/10 October 1875 at Krasny Rog, in Chernigov province), born Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (Алексей Константинович Толстой). Contents. Biography. Descended from illustrious aristocratic families on both sides, Aleksey was a distant cousin of the novelist Lev Tolstoy. Shortly after his birth, however, his parents separated and he was taken by his mother to Chernigov province in the Ukraine where he grew up under the wing of his uncle, Aleksey Perovsky (1787–1836), who wrote novels and stories under the pseudonym "Anton Pogorelsky". With his mother and uncle Aleksey travelled to Europe in 1827, touring Italy and visiting Goethe in Weimar. Goethe would always remain one of Tolstoy's favourite poets, and in 1867 he made notable translations of Der Gott und die Bajadere and Die Braut von Korinth . In 1834, Aleksey was enrolled at the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where his tasks included the cataloguing of historical documents. Three years later he was posted to the Russian Embassy at the Diet of the German Confederation in Frankfurt am Main. In 1840, he returned to Russia and worked for some years at the Imperial Chancery in Saint Petersburg. During the 1840s Tolstoy wrote several lyric poems, but they were not published until many years later, and he contented himself with reading them to his friends and acquaintances from the world of Saint Petersburg high society. At a masked ball in the winter season of 1850/51 he saw for the first time Sofya Andreyevna Miller (1825–1895), with whom he fell in love, dedicating to her the fine poem Amid the Din of the Ball (Средь шумного бала), which Tchaikovsky would later immortalize in one of his most moving songs (No. -

Hclassification

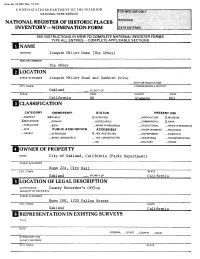

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco

From Triumphal Gates to Triumphant Rotting: Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie A. Kivelson, Chair Assistant Professor Paolo Asso Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo Assistant Professor Benjamin B. Paloff With much gratitude to Valerie Kivelson, for her unflagging support, to Yana, for her coffee and tangerines, and to the Prawns, for keeping me sane. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter I. Writing Empire: Lomonosov’s Rivalry with Imperial Rome ................................... 31 II. Qualifying Empire: Morals and Ethics of Derzhavin’s Romans ............................... 76 III. Freedom, Tyrannicide, and Roman Heroes in the Works of Pushkin and Ryleev .. 122 IV. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov and the Rejection of the Political [Rome] .................. 175 V. Blok, Catiline, and the Decomposition of Empire .................................................. 222 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 271 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITION ENGL 315 Fall 2011 Instructor: Michaela Bronstein, [email protected] Monday/Wednesday 2.00-3.20

THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITION ENGL 315 Fall 2011 Instructor: Michaela Bronstein, [email protected] Monday/Wednesday 2.00-3.20, BARR 102 Drop-in office hours: Monday 12-2, Johnson Chapel #5 (Please e-mail to schedule meetings at any other time.) I wish to speak out about several matters even though my artistry goes smash. What attracts me is what has piled up in my mind and heart; let it give only a pamphlet, but I shall speak out. —Fyodor Dostoevsky, letter regarding his novel Demons Revolutionist and reactionary, victim and executioner, betrayer and betrayed, they shall all be pitied together when the light breaks on our black sky at last. Pitied and forgotten … —Natalia Haldin, Under Western Eyes, Joseph Conrad Contrary to the hope Conrad’s character expresses, we have not forgotten either the historical revolutionaries or the works they inspired. While Dostoevsky feared that his novel was too politically pointed to be a lasting work of art, Demons today is more well-known than the incident on which the novel was based. In this course we will analyze the afterlives of nineteenth-century novels about revolutionaries—not just their continuing interest, but their constant reappearance in later works. Dostoevsky’s worries about his novel turning into a “pamphlet” raise a broad issue for the novel form: why would an author who wishes to address pressing social issues write a novel rather than an essay? How do authors reconcile the long aims of literature with the urgent claims of the political present? Revolutionaries often appeal to their authors precisely because they seem to represent much more than the social problem they seek to reform—whether they represent the influence of ideology upon character or the difficulty of human attempts to plot better lives for themselves and others, revolutionaries usually carry the weight of much more abstract ideas than their immediate social purposes.