Poulenc Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordination Des Syndicats CGT

Coordination des syndicats CGT STRATEGIE DE LA DIRECTION DU GROUPE SANOFI CONSEQUENCES INDUSTRIELLES ET SOCIALES Document d’août 2014 1. Situation économique – Coût du capital p2 2. Evolution des effectifs – Bilan des restructurations majeures p3 3. Stratégie Sanofi 2009-2015 : Désengagement scientifique et industriel en Europe et plus particulièrement en France p4 4. Stratégie de structuration du groupe en entités qui peuvent être cédées, vendues, fermées, échangées. p6 5. Crédit d’impôt – Des aides publiques pour quel usage ? p7 6. Industrie pharmaceutique : des besoins fondamentaux p7 7. Interpellation des élus et du gouvernement p8 1. Situation économique – Coût du capital Première entreprise pharmaceutique française et européenne. Sanofi est issu de la fusion de nombreux laboratoires pharmaceutiques français dont les principaux étaient Roussel Uclaf, Rhône Poulenc, Synthelabo, Sanofi et de l’allemand Hoechst. Sanofi représente 30 à 40% du potentiel national (effectifs, sites, R&D,…) de l’industrie pharmaceutique française dans notre pays. L’avenir du groupe et de ses activités en France conditionne l’avenir de l’industrie pharmaceutique française et constitue un élément incontournable de l’indépendance thérapeutique du pays. Le C.A. de sanofi dans le monde sur 2013 a atteint 33 milliards € et devrait se situer à un niveau légèrement supérieur en 2014. Plusieurs médicaments de référence étant aujourd’hui tombés dans le domaine public, le chiffre d’affaires repart à la hausse. Le résultat net des activités a été de 6,8 milliards € en 2013 et les projections sur 2014 laissent envisager une progression de 5% de celui-ci. La rentabilité est estimée par les économistes parmi les meilleures de l’industrie pharmaceutique dans le monde. -

Karl Heinz Roth Die Geschichte Der IG Farbenindustrie AG Von Der Gründung Bis Zum Ende

www.wollheim-memorial.de Karl Heinz Roth Die Geschichte der I.G. Farbenindustrie AG von der Gründung bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik Einleitung . 1 Vom „Dreibund“ und „Dreierverband“ zur Interessengemeinschaft: Entwicklungslinien bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs . 1 Der Weg zurück zum Weltkonzern: Die Interessengemeinschaft in der Weimarer Republik . 9 Kehrtwende in der Weltwirtschaftskrise (1929/30–1932/33) . 16 Norbert Wollheim Memorial J.W. Goethe-Universität / Fritz Bauer Institut Frankfurt am Main 2009 www.wollheim-memorial.de Karl Heinz Roth: I.G. Farben bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik, S. 1 Einleitung Zusammen mit seinen Vorläufern hat der I.G. Farben-Konzern die Geschichte der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts in exponierter Stellung mitgeprägt. Er be- herrschte die Chemieindustrie Mitteleuropas und kontrollierte große Teile des Weltmarkts für Farben, Arzneimittel und Zwischenprodukte. Mit seinen technolo- gischen Innovationen gehörte er zu den Begründern des Chemiezeitalters, das die gesamte Wirtschaftsstruktur veränderte. Auch die wirtschaftspolitischen Rahmenbedingungen gerieten zunehmend unter den Einfluss seiner leitenden Manager. Im Ersten Weltkrieg wurden sie zu Mitgestaltern einer aggressiven „Staatskonjunktur“, hinter der sich die Abgründe des Chemiewaffeneinsatzes, der Kriegsausweitung durch synthetische Sprengstoffe, der Ausnutzung der Annexi- onspolitik und der Ausbeutung von Zwangsarbeitern auftaten. Nach dem Kriegs- ende behinderten die dabei entstandenen Überkapazitäten die Rückkehr zur Frie- denswirtschaft -

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie Synthetic Worlds Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2005 Copyright © Esther Leslie 2005 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Colour printed by Creative Print and Design Group, Harmondsworth, Middlesex Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Leslie, Esther, 1964– Synthetic worlds: nature, art and the chemical industry 1.Art and science 2.Chemical industry - Social aspects 3.Nature (Aesthetics) I. Title 7-1'.05 isbn 1 86189 248 9 Contents introduction: Glints, Facets and Essence 7 one Substance and Philosophy, Coal and Poetry 25 two Eyelike Blots and Synthetic Colour 48 three Shimmer and Shine, Waste and Effort in the Exchange Economy 79 four Twinkle and Extra-terrestriality: A Utopian Interlude 95 five Class Struggle in Colour 118 six Nazi Rainbows 167 seven Abstraction and Extraction in the Third Reich 193 eight After Germany: Pollutants, Aura and Colours That Glow 218 conclusion: Nature’s Beautiful Corpse 248 References 254 Select Bibliography 270 Acknowledgements 274 Index 275 introduction Glints, Facets and Essence opposites and origins In Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow a character remarks on an exploding missile whose approaching noise is heard only afterwards. The horror that the rocket induces is not just terror at its destructive power, but is a result of its reversal of the natural order of things. -

Ce Que Sanofi Dit De La Politique Industrielle Française

Ce que Sanofi dit de la politique industrielle française mediapart.fr/journal/economie/030221/ce-que-sanofi-dit-de-la-politique-industrielle-francaise Martine Orange, Mediapart, 3 février 2021 Les salariés de Sanofi ont beau essayer de chercher des explications, ils ne comprennent pas. Ou plutôt ils ne comprennent que trop bien la conduite du groupe pharmaceutique. Après le revers de sa stratégie dans l’élaboration d’un vaccin contre le Covid-19, repoussé désormais au mieux à la fin de l’année, tout aurait dû pousser la direction de Sanofi à s’interroger sur la pertinence de ses choix, sur la place laissée à la recherche jugée comme essentielle. Mais rien ne s’est passé. Le 28 janvier, la direction de Sanofi Recherche et Développement en France a confirmé à l’occasion d’un comité social d’entreprise (CSE) la suppression de 364 emplois en France, une mesure qui vise particulièrement l’unité de Strasbourg appelée à être transférée en région parisienne. Ce plan s’inscrit dans un programme plus large annoncé en juillet 2020. Le groupe entend supprimer 1 700 emplois en Europe dont un millier en France sur trois ans. « Mais ce n’est qu’une partie du projet Pluton, prévient Jean-Louis Perrin, délégué CGT à Montpellier. Sanofi est en train de se désindustrialiser. Toute la pharmacie de synthèse est appelée à disparaître dans le groupe. Les sites de Sisteron, Elbeuf, Vertolaye, Brindisi (Italie), Francfort (Allemagne), Haverhill (Royaume-Uni), Újpest (Hongrie) sont destinés à sortir du groupe. Au total, cela représente 3 500 emplois. » Centre de distribution de Sanofi à Val-de-Reuil. -

Fusiones 20De 20Labo

"Cuando los grandes se hacen gigantes" Fusiones de Laboratorios 1 INDICE PRÓLOGO……………………………………………………………………………...…….. 3 INTRODUCCIÓN: FUSIONES Y ADQUISICIONES…………………………………..….. 4 INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO………………………………………………………. 5 LA INDUSTRIA FARMACEUTICA………………………………………………………. 16 FUSIÓN SANOFI – AVENTIS…………………………………………………………...… 20 FUSIÓN BAYER – SCHERING……………………………………………………………. 26 FUSIÓN PFIZER – WYETH……………………………………………………………….. 30 FUSIÓN MERCK & CO. – SCHERING PLOUGH…………………………………..……. 31 FUSIÓN ROCHE – GENENTECH………………………………………………………… 34 MERCADOS REGIONALES………………………………………………………….…… 40 LA INDUSTRIA FARMACÉUTICA EN LA ARGENTINA……………………...………. 42 CONCLUSIÓN……………………………………………………………………………… 49 2 PRÓLOGO Es un verdadero privilegio que hayan pensado en mí para prologar este interesante trabajo relacionado con la formación profesional de estos inquietos alumnos de la Carrera de Agentes de Propaganda Médica. Grato además, pues recrea mi participación activa en el mundo de la Industria Farmacéutica, en calidad de Asesor de la Fuerza de Ventas e Investigador Principal durante varias décadas, período que fue enriquecedor para mí y sumó un importante valor agregado a mi bagaje médico y personal. Entiendo que lo sucedido en los avances científicos y tecnológicos durante los últimos cuarenta años, ha constituido un quiebre en la Historia de la Medicina y, por lo tanto, de la Humanidad. Es por ello que veo con beneplácito que la formación de estos entusiastas jóvenes va de la mano con los cambios de planes y esquemas de estudios de los futuros médicos. -

The Life of the Abortion Pill in the United States

The Life of the Abortion Pill in the United States The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation The Life of the Abortion Pill in the United States (2000 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8852153 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 80 The Life of the Abortion Pill in the United States Julie A. Hogan Eleven years after mifepristone1, the drug that chemically induces abortion and hence coined the abortion pill, was approved for use in France, American women still do not have access to the drug, although women in at least ten other nations do.2 In 1988, Americans thought the Abortion Pill [was] on the Hori- zon.3 In 1993, almost five years later, American women still did not have access to the drug, although many women's hopes were raised by newspaper headlines claiming that the Door May Be Open for [the] Abortion Pill to Be Sold in [the] U.S.4 and newspaper accounts predicting that mifepristone would be available in the United States in 1996.5 In 1996, the headlines reported that the Approval of [the] Abortion Pill by the FDA [was] Likely Soon.6 Yet, mifepristone was still not available in 1999, and newspaper headlines were less optimistic about pre- 1Mifepristone is the generic name for RU-486, the designation given the drug by its French maker, Roussel-Uclaf. -

1998 Annual Report BASF Group

Excellence in chemistry 1998 Annual Report BASF Group Million DM 1998 1997 Change % Sales 54,065 55,780 – 3.1 Income from operations 5,132 5,342 – 3.9 Profit before taxes 5,419 5,331 + 1.7 Net income after taxes and minority interests 3,324 3,236 + 2.7 Cash flow 7,258 7,225 + 0.5 Capital expenditures 5,671 4,359 + 30.1 Research and development expense 2,561 2,549 + 0.5 Dividend paid by BASF Aktiengesellschaft 1,355 1,244 + 8.9 Dividend per share in DM 2.20 2.00 + 10.0 Number of employees (December 31) 105,945 104,979 + 0.9 Segments Sales 1998 1997 Change Million DM % Health & Nutrition 9,970 8,972 + 11.1 Colorants & Finishing Products 12,104 12,791 – 5.4 Chemicals 10,141 10,675 – 5.0 Plastics & Fibers 14,812 14,463 + 2.4 Oil & Gas 5,251 6,255 – 16.1 Other* 1,787 2,624 – 31.9 54,065 55,780 – 3.1 Income from operations 1998 1997 Change Million DM Million DM Health & Nutrition 750 680 + 70 Colorants & Finishing Products 1,256 939 + 317 Chemicals 1,861 2,203 – 342 Plastics & Fibers 1,054 720 + 334 Oil & Gas 540 926 – 386 Other* – 329 –126 – 203 5,132 5,342 – 210 Regions (location of customers) Sales 1998 1997 Change Million DM % Europe 32,607 34,112 – 4.4 • thereof Germany (13,713) (14,380) – 4.6 North America (NAFTA) 12,222 11,668 + 4.7 Presented to the 47th Annual Meeting on Thursday, April 29, 1999, South America 3,209 3,278 – 2.1 10.00 a.m., at BASF Feierabend- haus, Leuschnerstrasse 47, Asia, Pacific Area, Africa 6,027 6,722 – 10.3 Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany. -

The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-7-1997 The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G. Robert Arthur Reinert Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Reinert, Robert Arthur, "The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G." (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5302. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Robert Arthur Reinert for the Master of Arts in History were presented May 7, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Sean Dobson, Chair ~IReard~n Louis Elteto Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: [)fl Dodds Department of History * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on ct</ ~~ /997 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Robert Arthur Reinert for the Master of Arts in History presented May 7, 1997. Title: The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of LG. Farben, A.G .. On a massive scale, German business elites linked their professional ambitions to the affairs of the Nazi State. By 1937, the chemical giant, l.G. Farben, became completely "Nazified" and provided Hitler with materials which were essential to conduct war. -

The Story of RU-486 in the United States

The Story of RU-486 in the United States The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation The Story of RU-486 in the United States (2001 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8889480 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 I. THE BIRTH OF A CONTROVERSY 2 A. Background: What is RU-486 and How Does It Work? 2 B. The French Abortion Pill Fury 3 II. POLITICS AND CHEMISTRY MAKE A VOLATILE MIXTURE: \KEEPING THE ABORTION PILL BOTTLED UP IN FRANCE" 7 A. Moral Concerns 7 A. Moral Concerns 7 B. Corporate America's Lack of Interest 8 B. Corporate America's Lack of Interest 8 C. Supreme Court Jurisprudence's Impact on RU-486 10 D. Abortion Politics Goes Conservative 13 E. Regulatory Restrictions on Abortion 13 III. THE ABORTION TIDE BEGINS TO TURN 17 A. A New Administration 17 B. The Involvement of the Population Council 19 C. Concern From the Pro-Life Movement 22 1 IV. THE TIDE TURNS AGAIN { The Political Pendulum Swings to the Right 25 A. The Politics of Abortion Run Into The Contract With America 25 B. Conservative Congressional Legislation 27 V. THE FDA APPROVAL PROCESS GETS UNDERWAY 29 V. -

Opemmundi E Ljbope

OpemMundi E lJBOPE A WEEKLY REPORT ON THE ECONOMY OF THE COMMON MARKET ----- ------- -- �--- --· ------ -- - -----·-----·--·-------- of ooo oo oo 0000000000 ��-ONTENTt-4.oo o_Q';)o o oq ooo oo 0000001 g�!. ·----- ---·--····-············· ······-----· __ :__ --- ------ - - - . : g 0 I 0 o I : o / o I : o o I : o 0g I /ffJ ;1 r'i\J : og o INDEX f .i trr rtn "� o _ _, ;.;,·� Jt\J T 0 '-"' 1.•'- l",, 0 , ...4 �� ..1' ., . 0 ft iii 0 0 0 0 JO 0 I 0 0 0 0o To Euroflash 0o 0 0 0 0 0 0 ,0 0 , g from No 468 to No 492 inclusive g .,0 0 !o o 1 o o 0 0 0 0 0 o July 4, 1968 - December 19 , 1963 °o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 · t;tlllOFLA.SH: llusiness 11enetration U('ross Europe o 01 0 0 :o g January 1969 Index No 11 · l g 0 :o 0 ,o 0 :o O :o 0 :o 0 :o 01 : 0 0 0 ooo -----------------------------------------------------o o oo o oo o oo oo oo o o_o oo o oo_o o o o o== oo--=:�� o o------o o o=:o -------------- oo o o oo oo �=� o-----o o o o Opera Mundi ElfR OPE A WEEKLY REPORT ON THE ECONOMY OF THE COMMON MARKET PUBLISHED ON BEHALF OF OPERA MUNDI BY EUROPEAN INTELLIGENCE LIMITED EUROPA HOUSE ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS KENT TEL 25202/4 TELEX 95114 OPERA MUNDI EUROPE 100 Avenue Raymond Poincar� - PARIS 16e TEL: KLE 54-12 34-21 - CCP PARIS 3235-50 EDITOR & PUBLISHER . -

Annual Report 2016

i Annual Report 2016 Sanofi completes half century in Pakistan 1967 - 2017 The company that is now known as Sanofi Pakistan has been present in Pakistan for 50 years, saving the lives of millions and improving the quality of life of many more through effective, top quality products. As we embark on the next 50 year mission, we stand firm to protect, enable and support people on their health journey through life, empowering them to live life to its full potential. Syed Babar Ali Chairman Sanofi-aventis Pakistan limited from the Pagesof History Historical Milestones Following global merger of Hoechst AG & Manufacturing of The company went Rhone Poulenc S.A. into a new company pharmaceuticals and public and was listed known as Aventis S.A., the name of the specialty chemicals on the Karachi Stock Start of Haemaccel® company in Pakistan was changed to started Exchange production Aventis Pharma (Pakistan) Limited 1972 1977 1995 2000 1967 1973 1979 1985 1998 2003 Company was Production of first Launch of Flagyl® Agrochemical Amaryl® launch • Company changed its incorporated as batch of commercial formulation name to Aventis Limited Hoechst Pakistan products started • Inception of Claforan® Limited plant Lemtrada® was administered Global blockbuster Plavix® Inauguration of liquid Launch of Genzyme for the first time in Pakistan to a launched in Pakistan manufacturing plant business in Pakistan patient of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) 2007 2010 2013 2016 2005 2008 2011 2012 2014 • Launch of Lantus® in Pakistan Sanofi Pasteur vaccines Change of identity -

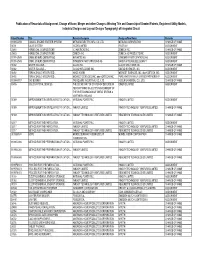

Publication of Recordals of Assignment, Change of Name

Publication of Recordals of Assignment, Change of Name, Merger and other Changes Affecting Title and Ownership of Granted Patents, Registered Utility Models, Industrial Designs and Lay-out Designs Topography) of Integrated Circuit Patent Number Title Patentee/Assignor Assignee/New Name Remarks 1199654059 COAXIAL ENGINE STARTER SYSTEM MITSUBA ELECTRIC MFG. CO. LTD. MITSUBA CORPORATION CHANGE OF NAME 31731 VALVE SYSTEM ISCOR LIMITED IPCOR NV ASSIGNMENT 25483 HERBICIDAL COMPOSITIONS ICI AMERICAS INC. ZENECA INC. CHANGE OF NAME 25483 HERBICIDAL COMPOSITIONS ZENECA INC. ZENECA AG PRODUCTS INC. ASSIGNMENT 1199142549 OXIME ETHERS DERIVATIVES NOVARTIS AG SYNGENTA PARTICIPATIONS AG ASSIGNMENT 1199142549 OXIME ETHERS DERIVATIVES SYNGENTA PARTICIPATIONS AG BAYER AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT ASSIGNMENT 31882 WATER SOLUBLE… GLAXO INC. GLAXO WELLCOME INC. CHANGE OF NAME 31882 WATER SOLUBLE… GLAXO WELLCOME INC. GILEAD SCIENCES, INC. ASSIGNMENT 31492 REPLACEABLE INTEGRATED… AMOS KORIN MIDWEST SCIENCES, INC. dba KORTECH, INC. ASSIGNMENT 31492 REPLACEABLE INTEGRATED… MIDWEST SCIENCES, INC. dba KORTECH, INC. PURE WATER FAMILY LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ASSIGNMENT 1199447817 GAS BURNER TRI-SQUARE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. HOSUN UNIVERSAL CO., LTD. CHANGE OF NAME 18495 LIQUID CRYSTAL DEVICES THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENSE IN QINETIQ LIMITED ASSIGNMENT HER BRITTANIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN & NORTHERN IRELAND 31389 IMPROVEMENTS IN OR RELATING TO CATION… NATIONAL POWER PLC INNOGY LIMITED ASSIGNMENT 31389 IMPROVEMENTS IN OR RELATING TO CATION…