A Samoan Reading of Discipleship in Matthew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Webster

DISCIPLESHIP AND CALLING }OHN WEBSTER, KINGS COLLEGE, UNNERSITY OF ABERDEEN I'm very grateful for the opportunity to spend this time with you reflecting on some issues about the theme of discipleship. My intention is to set our minds to work by offering a theological account of Christian discipleship, and to that end I have divided the material into two themes: 'Discipleship and Calling', and 'Discipleship and Obedience'. In arranging the topic in this way, I am reiterating what I take to be a twofold gospel principle for the theology of the Christian life, namely, that grace both precedes and commands action. In this first session, I propose to reflect on the call to discipleship, and above all on the one who constitutes that call, Jesus Christ, who is himself the grace and command of God in person. Tomorrow I propose to go on from there to consider the shape or direction of discipleship in response to the summons of Jesus. Our questions, therefore, are: who is Jesus Christ? Who are those whom he calls to follow him? And how are we to characterise the life to which he calls them? Such, I hope to suggest, are the basic elements of a theology of discipleship. Before I move into the exposition itself, however, I want to stand back and speak a little more generally about the place which the topic of discipleship has in the more general theology of the Christian life. DISCIPLESHIP IN THE THEOLOGY OF THE CHURCH The task of a theology of the Christian life is to describe that form of human existence which is brought into being and upheld by the saving work of God. -

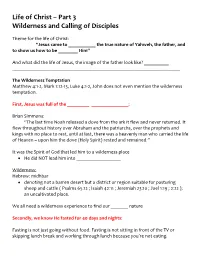

Life of Christ – Part 3 Wilderness and Calling of Disciples

Life of Christ – Part 3 Wilderness and Calling of Disciples Theme for the life of Christ: “Jesus came to ___________ the true nature of Yahweh, the father, and to show us how to be ________ Him” And what did the life of Jesus, the image of the father look like? __________ ____________________________________________________________________ The Wilderness Temptation Matthew 4:1-2, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-2, John does not even mention the wilderness temptation. First, Jesus was full of the _________ _______________: Brian Simmons: “The last time Noah released a dove from the ark it flew and never returned. It flew throughout history over Abraham and the patriarchs, over the prophets and kings with no place to rest, until at last, there was a heavenly man who carried the life of Heaven – upon him the dove (Holy Spirit) rested and remained.” It was the Spirit of God that led him to a wilderness place He did NOT lead him into __________________ Wilderness: Hebrew: midhbar denoting not a barren desert but a district or region suitable for pasturing sheep and cattle ( Psalms 65:12 ; Isaiah 42:11 ; Jeremiah 23:10 ; Joel 1:19 ; 2:22 ); an uncultivated place. We all need a wilderness experience to find our _______ nature Secondly, we know He fasted for 40 days and nights: Fasting is not just going without food. Fasting is not sitting in front of the TV or skipping lunch break and working through lunch because you’re not eating. Fasting Biblically is: Going without ___________ for a spiritual purpose It’s purpose is to solely bring us into a deeper, more intimate relationship with God. -

The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview

St. John’s Lutheran Church, Adult Education Series, Spring 2019 “The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview A. The Four Gospels – Greek, euangelion, “good news,” Old English, god-spel “Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31) 1. Mark a. author likely John Mark, cousin of Barnabas (Col 4:10), companion of Peter (Acts 12:12) and Paul (Acts 12:12, 15:37-38) b. written ca 50-65 AD, perhaps after death of Peter c. likely written to Gentile Christians in Rome d. focus on Jesus as the Son of God 2. Matthew a. author likely Matthew (Levi), one of the Twelve Apostles b. written ca 60-70 AD c. likely written to Jewish Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Messiah 3. Luke a. author likely Luke, physician, companion of Paul (Col 4:14), author of Acts, gives an orderly account (1:1-4) b. written ca 60-70 AD c. addressed to Theophilus (Greek, “lover of God”), Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Savior of all people 4. John a. author possibly John, one of the Twelve Apostles – identifies himself as the “beloved disciple” (John 21:20) b. written ca 80-100 AD c. addressed to Jewish and Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as God incarnate 1 St. -

Matthew 4:18-23New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) 18 As He

1 Matthew 4:18-23New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) 18 As he walked by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea—for they were fishermen. 19 And he said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” 20 Immediately they left their nets and followed him. 21 As he went from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John, in the boat with their father Zebedee, mending their nets, and he called them. 22 Immediately they left the boat and their father, and followed him.23 Jesus[a] went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the good news[b] of the kingdom and curing every disease and every sickness among the people. In today’s scripture passage, we hear Jesus calling his first followers. Because we have read the rest of the story, we know these are four of Jesus’ disciples but this passage does not call them disciples. What I think is important for us to note is that Jesus seeks out these individuals. They are in the midst of doing their jobs, going about business as usual, and honestly, there is no indication of a prior relationship with Jesus. But Jesus calls and they respond. Will you? Let us pray. Gracious God, help us to open our hearts and minds to hear what you have to say to us this day. Help us to listen for your call and respond as faithful disciples. -

Israel & Palestine Past and Present

The Holy Land: Israel & Palestine Past and Present Christian begins in the Holy Land with the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary in the city of Nazareth. Christian then shifts to the City of David, Bethlehem with the birth of Jesus The Wedding in Cana The Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist The Temptation The Monastery of the Temptation (Orthodox), just north of Jericho The Scene shifts to the Sea of Galilee The Calling of the Disciples 1st Century Boat discovered in the mid 1980’s at the Sea of Galilee. Housed at the Kibbutz Ginosar The town of Tabkha (Tabgha) is the location of two of Christianity’s most powerful Important moments: The Feeding of the Five Thousand & The Sermon on the Mount Mosaic Fragment from 5th Century, Church of the Multitude in Tabkha, Israel Church of the Beautitudes, Tabhka, Israel The Holy Land: Israel & Palestine Past and Present 6th Century Mosaic, Greek Inscription, “Hagia polis ierosalem (Holy City Jerusalem)” Jerusalem as the Center of the World Map circa 12th Century Jesus came to the Temple in Jerusalem 5 Times according to the New Testament: 1. Twelve Years Old for his dedication (Luke) 2. Teach in the Temple Courtyard (John) 3. Teach in the courtyard and heal the blind man in the Pool of Siloam (John) 4. Teach in the Courtyard and is nearly stoned (John) 5. Holy Week (All Four Gospels) Caravaggio, circa 1610, “The Money Changers” He Qi, 2013 “Triumphant Entry” Stained Glass at St. James Anglican Church, Liverpool, 17th Century. “Render Unto Caesar” The Last Supper commemorated at The Cenacle Mary tells -

Rites of Maymar of Archangel Michael ﻣﯾﻣر رﺋﯾس اﻟﻣﻼﺋﮐﺔ اﻟﺟﻟﯾل ﻣﯾﺧﺎﺋﯾل

Rites of Maymar of Archangel Michael ميمر رئيس المﻻئكة الجليل ميخائيل Fr. Jacob Nadian St. Bishoy Coptic Orthodox Church of Toronto Stouffville, ON Canada 1 H.H. Pope Tawadros, II Pope and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark, The Coptic Orthodox Church In Egypt and Abroad 2 Rites of Maymar of Archangel Michael طقس ميمر رئيس المﻻئكة الجليل ميخائيل Table of Contents Part 1: The Archangel Michael ....................................................................................................4 1. What is Maymar? .................................................................................................................... 4 2. The Meaning of the Name “Michael” ..................................................................................... 4 3. The Archangel Michael in the Holy Bible .............................................................................. 5 Part 2: Miracles of Archangel Michael ........................................................................................9 Part 3: Rites of Maymar of Archangel Michael ........................................................................10 The Prayer of Thanksgiving...................................................................................................... 11 Verses of Cymbals .................................................................................................................... 14 Adam Verses of Cymbals (Sunday to Tuesday) ................................................................... 14 Watos Verses of Cymbals (Wednesday to Saturday) -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter (Pt.4)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 2019 Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter (Pt.4) Paul N. Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Christianity Commons Search “Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter” (Pt.4) By Paul N. Anderson George Fox University Newberg, Oregon https://georgefox.academia.edu/PaulAnderson (https://georgefox.academia.edu/PaulAnderson) April 2019 The final two episodes of the History Channel’s “Jesus: His Life” focus on Jesus as viewed by Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter. As with the previous six episodes, this hybrid documentary focuses on the life of Jesus from the perspectives of particular individuals within the gospel narratives. Over and against more historical-critical and skepticism- privileging series a couple of decades ago,[1] this series largely follows the presentations of Jesus within the four canonical gospels, while still setting them within the contexts of first century Palestine under the Roman Empire. In so doing, the softer view of New Testament historiography pioneered by James Dunn, “Jesus Remembered,” is applied effectively, as the life of Jesus is examined as it might have been perceived and remembered by different figures within the gospel narratives themselves.[2] This more nuanced approach to gospel historiography allows scholars leeway in presenting not only what happened, but also sketching how key figures would have perceived and referenced particular events, including a diversity of understandings and viewpoints within and beyond the gospel witness.[3] That being the case, differences between the Gospels (especially between John and the Synoptics) can be accounted for more readily, rather than choosing sides in one direction over another. -

Discipleship and Mission

Discipleship and Mission GENERAL INTRODUCTION This quarter surveys several calls to ministry and the expectations of those called. Calls to service, as recorded in the gospels of Mark and Luke, are highlighted. We explore Paul’s call to ministry, with special attention to the Roman church. On Easter Sunday, we examine Matthew’s account of the Resurrection. Unit I, “Call to Discipleship,” has four lessons and highlights several aspects of what it means to be called by Jesus as a disciple. They include hospitality, counting the cost, reaching the lost, and salvation for all people. Unit II, “Call to Ministry,” has five lessons that explore the diverse ways in which Jesus’ disciples were challenged to exercise their call to ministry: by witnessing to the Gospel message, acting with loving kindness, sharing the Resurrection story, and making new disciples through preaching, teaching, and baptism. Unit III, “The Spread of the Gospel” (four lessons), begins with Paul’s introduction of himself to the Jewish and Gentile Christians living in Rome. Paul affirms that the call to salvation is to Israel and to Gentiles. This call to salvation is a call to a life in the Spirit and involves a new life in Christ. Spring 2018–TOWNSEND PRESS COMMENTARY | 1 2 | TOWNSEND PRESS COMMENTARY–Spring 2018 March 3, 2019 Lesson 1 CALLED TO HUMILITY AND HOSPITALITY ADULT/YOUTH CHILDREN ADULT/YOUNG ADULT TOPIC: Humility Is Good GENERAL LESSON TITLE: Called to Be Humble for You and Kind YOUTH TOPIC: Sitting with the Lowly CHILDREN’S TOPIC: Dare to Care and Share DEVOTIONAL READING Luke 14:15-24 ADULT/YOUTH BACKGROUND SCRIPTURE: Luke 14:7-14 BACKGROUND SCRIPTURE: Luke 14:7-14 PRINT PASSAGE: Luke 14:7-14 PRINT PASSAGE: Luke 14:7-14 KEY VERSES: Luke 14:13-14a KEY VERSE: Luke 14:11 CHILDREN Luke 14:7-14—KJV Luke 14:7-14—NIV 7 And he put forth a parable to those which 7 When he noticed how the guests picked were bidden, when he marked how they chose the places of honor at the table, he told them this out the chief rooms; saying unto them. -

A History of Hip Hop in Halifax: 1985 - 1998

HOW THE EAST COAST ROCKS: A HISTORY OF HIP HOP IN HALIFAX: 1985 - 1998 by Michael McGuire Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2011 © Copyright by Michael McGuire, 2011 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a thesis entitled “HOW THE EAST COAST ROCKS: A HISTORY OF HIP HOP IN HALIFAX: 1985 - 1998” by Michael McGuire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Dated: August 18, 2011 Supervisor: _________________________________ Readers: _________________________________ _________________________________ ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: August 18, 2011 AUTHOR: Michael McGuire TITLE: How the East Coast Rocks: A History Of Hip Hop In Halifax: 1985 - 1998 DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Department of History DEGREE: MA CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2011 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the -

The Edge of Ladyspace: Ladi6 and the Political Limits of Self-Branding

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id6 - ARTICLE - The Edge of Ladyspace: Ladi6 and the Political Limits of Self-Branding Annalise Friend Abstract Musicians connected through online and offline networks make use of a personal brand to represent themselves and their work. This self-branding must be recognisable, repetitive, and ‘fresh’ if it is to cut through the deluge of contemporary media content. The brands of politically engaged performers—referred to as ‘conscious’ performers—often revolve around political critique, ‘oneness’, and personal and spiritual uplift. These notions are often placed in opposition to the apparent commodification of performers through practices of personal branding. The circulation and consumption of personal brands may not necessarily however, preclude the impact of apparent political critique. This article will explore how the Samoan Aotearoa-New Zealander vocalist Ladi6 plays with the role of ‘lady’ in her brand as a politically engaged strategy. Ladi6 draws on genre resources from conscious hip-hop, soul, reggae, and electronic music. Her assertion of female presence, or creation of a ‘ladyspace’, is both ambiguous and reflexive. While the production of her personal brand—found in videos, lyrics, photos, online presence, merchandise, and live performances—operates according to the logics of global capitalism; the consumption of this brand can provide an alternative ‘conscious’ mode of engagement with the Ladi6 musical commodity. Introduction This article presents Ladi6 (Karoline Tamati) as a case study of a performer who uses the role of being a ‘conscious’ artist as her personal brand. This type of branding implies that her lyrical and musical content is politically critical. -

11 July 2021 Martyr Euphemia the All-Praised and Olga (Helen), Princess of Kiev

SAINT GEORGE ORTHODOX CHURCH 211 E. Minnesota St., Spring Valley, IL 61362 815-664-4540 www.springvalleyorthodox.com Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America Metropolitan JOSEPH Diocese of Toledo and the Midwest Bishop ANTHONY “One, Holy, Catholic & Apostolic Church” 11 JuLy 2021 martyr Euphemia the all-praised and Olga (Helen), princess of Kiev OrthrOs, 8:45 am • Divine Liturgy, 10:00 am Presiding: Bishop Anthony Pastor: Father Mark Sahady Ecclesiarch: Michael Baum Sacristan: David Anderson Parish council members: Melanie Thompson, Chair Genie Sanders, Chanters/Choir Mark Kerasotes, Vice-Chair Dee Khoury, Antiochian Women Ronald Malooley, Treasurer David Anderson, Sunday School Michael Kasap, Secretary Wayne Sanders, Facilities George Nimee Markella Fousekas 11 July 2021 1 Sunday Bulletin BULLETIN PART ONE – ANNOUNCEMENTS CHURCH FINANCES May 2021 Income-Expense May 2021 Income Breakout Total May Income: $4,297.10 Flower Donations: $85 Total May Expenses: $6,222.70 Food For Hungry Alms: $66.10 Net Income May: $-1,925.60 Total Above Donations: $151.10 Total Jan-May Income: $33,366.34 Stewardship Offerings: $4,146 Total Jan-May Expenses: $29,125.34 Net Income Jan-May: $4,241.00 Thank you to all our parishioners, friends, donors and benefactors for your support. God loves a cheerful giver. (2 Corinthians 9:7b) All of Creation, everything we have belongs to God. We are Stewards of His Gifts. We are to give thanks to God for allowing us to use His Gifts by giving back a tenth. + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +