John Webster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life of Christ – Part 3 Wilderness and Calling of Disciples

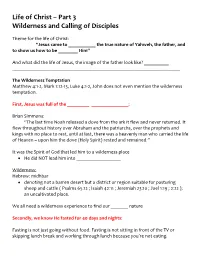

Life of Christ – Part 3 Wilderness and Calling of Disciples Theme for the life of Christ: “Jesus came to ___________ the true nature of Yahweh, the father, and to show us how to be ________ Him” And what did the life of Jesus, the image of the father look like? __________ ____________________________________________________________________ The Wilderness Temptation Matthew 4:1-2, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-2, John does not even mention the wilderness temptation. First, Jesus was full of the _________ _______________: Brian Simmons: “The last time Noah released a dove from the ark it flew and never returned. It flew throughout history over Abraham and the patriarchs, over the prophets and kings with no place to rest, until at last, there was a heavenly man who carried the life of Heaven – upon him the dove (Holy Spirit) rested and remained.” It was the Spirit of God that led him to a wilderness place He did NOT lead him into __________________ Wilderness: Hebrew: midhbar denoting not a barren desert but a district or region suitable for pasturing sheep and cattle ( Psalms 65:12 ; Isaiah 42:11 ; Jeremiah 23:10 ; Joel 1:19 ; 2:22 ); an uncultivated place. We all need a wilderness experience to find our _______ nature Secondly, we know He fasted for 40 days and nights: Fasting is not just going without food. Fasting is not sitting in front of the TV or skipping lunch break and working through lunch because you’re not eating. Fasting Biblically is: Going without ___________ for a spiritual purpose It’s purpose is to solely bring us into a deeper, more intimate relationship with God. -

The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview

St. John’s Lutheran Church, Adult Education Series, Spring 2019 “The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview A. The Four Gospels – Greek, euangelion, “good news,” Old English, god-spel “Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31) 1. Mark a. author likely John Mark, cousin of Barnabas (Col 4:10), companion of Peter (Acts 12:12) and Paul (Acts 12:12, 15:37-38) b. written ca 50-65 AD, perhaps after death of Peter c. likely written to Gentile Christians in Rome d. focus on Jesus as the Son of God 2. Matthew a. author likely Matthew (Levi), one of the Twelve Apostles b. written ca 60-70 AD c. likely written to Jewish Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Messiah 3. Luke a. author likely Luke, physician, companion of Paul (Col 4:14), author of Acts, gives an orderly account (1:1-4) b. written ca 60-70 AD c. addressed to Theophilus (Greek, “lover of God”), Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Savior of all people 4. John a. author possibly John, one of the Twelve Apostles – identifies himself as the “beloved disciple” (John 21:20) b. written ca 80-100 AD c. addressed to Jewish and Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as God incarnate 1 St. -

Matthew 4:18-23New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) 18 As He

1 Matthew 4:18-23New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) 18 As he walked by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea—for they were fishermen. 19 And he said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” 20 Immediately they left their nets and followed him. 21 As he went from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John, in the boat with their father Zebedee, mending their nets, and he called them. 22 Immediately they left the boat and their father, and followed him.23 Jesus[a] went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the good news[b] of the kingdom and curing every disease and every sickness among the people. In today’s scripture passage, we hear Jesus calling his first followers. Because we have read the rest of the story, we know these are four of Jesus’ disciples but this passage does not call them disciples. What I think is important for us to note is that Jesus seeks out these individuals. They are in the midst of doing their jobs, going about business as usual, and honestly, there is no indication of a prior relationship with Jesus. But Jesus calls and they respond. Will you? Let us pray. Gracious God, help us to open our hearts and minds to hear what you have to say to us this day. Help us to listen for your call and respond as faithful disciples. -

Israel & Palestine Past and Present

The Holy Land: Israel & Palestine Past and Present Christian begins in the Holy Land with the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary in the city of Nazareth. Christian then shifts to the City of David, Bethlehem with the birth of Jesus The Wedding in Cana The Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist The Temptation The Monastery of the Temptation (Orthodox), just north of Jericho The Scene shifts to the Sea of Galilee The Calling of the Disciples 1st Century Boat discovered in the mid 1980’s at the Sea of Galilee. Housed at the Kibbutz Ginosar The town of Tabkha (Tabgha) is the location of two of Christianity’s most powerful Important moments: The Feeding of the Five Thousand & The Sermon on the Mount Mosaic Fragment from 5th Century, Church of the Multitude in Tabkha, Israel Church of the Beautitudes, Tabhka, Israel The Holy Land: Israel & Palestine Past and Present 6th Century Mosaic, Greek Inscription, “Hagia polis ierosalem (Holy City Jerusalem)” Jerusalem as the Center of the World Map circa 12th Century Jesus came to the Temple in Jerusalem 5 Times according to the New Testament: 1. Twelve Years Old for his dedication (Luke) 2. Teach in the Temple Courtyard (John) 3. Teach in the courtyard and heal the blind man in the Pool of Siloam (John) 4. Teach in the Courtyard and is nearly stoned (John) 5. Holy Week (All Four Gospels) Caravaggio, circa 1610, “The Money Changers” He Qi, 2013 “Triumphant Entry” Stained Glass at St. James Anglican Church, Liverpool, 17th Century. “Render Unto Caesar” The Last Supper commemorated at The Cenacle Mary tells -

Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter (Pt.4)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 2019 Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter (Pt.4) Paul N. Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Christianity Commons Search “Jesus: His Life from the Perspectives of Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter” (Pt.4) By Paul N. Anderson George Fox University Newberg, Oregon https://georgefox.academia.edu/PaulAnderson (https://georgefox.academia.edu/PaulAnderson) April 2019 The final two episodes of the History Channel’s “Jesus: His Life” focus on Jesus as viewed by Mary Magdalene and the Apostle Peter. As with the previous six episodes, this hybrid documentary focuses on the life of Jesus from the perspectives of particular individuals within the gospel narratives. Over and against more historical-critical and skepticism- privileging series a couple of decades ago,[1] this series largely follows the presentations of Jesus within the four canonical gospels, while still setting them within the contexts of first century Palestine under the Roman Empire. In so doing, the softer view of New Testament historiography pioneered by James Dunn, “Jesus Remembered,” is applied effectively, as the life of Jesus is examined as it might have been perceived and remembered by different figures within the gospel narratives themselves.[2] This more nuanced approach to gospel historiography allows scholars leeway in presenting not only what happened, but also sketching how key figures would have perceived and referenced particular events, including a diversity of understandings and viewpoints within and beyond the gospel witness.[3] That being the case, differences between the Gospels (especially between John and the Synoptics) can be accounted for more readily, rather than choosing sides in one direction over another. -

Discipleship and Mission

Discipleship and Mission GENERAL INTRODUCTION This quarter surveys several calls to ministry and the expectations of those called. Calls to service, as recorded in the gospels of Mark and Luke, are highlighted. We explore Paul’s call to ministry, with special attention to the Roman church. On Easter Sunday, we examine Matthew’s account of the Resurrection. Unit I, “Call to Discipleship,” has four lessons and highlights several aspects of what it means to be called by Jesus as a disciple. They include hospitality, counting the cost, reaching the lost, and salvation for all people. Unit II, “Call to Ministry,” has five lessons that explore the diverse ways in which Jesus’ disciples were challenged to exercise their call to ministry: by witnessing to the Gospel message, acting with loving kindness, sharing the Resurrection story, and making new disciples through preaching, teaching, and baptism. Unit III, “The Spread of the Gospel” (four lessons), begins with Paul’s introduction of himself to the Jewish and Gentile Christians living in Rome. Paul affirms that the call to salvation is to Israel and to Gentiles. This call to salvation is a call to a life in the Spirit and involves a new life in Christ. Spring 2018–TOWNSEND PRESS COMMENTARY | 1 2 | TOWNSEND PRESS COMMENTARY–Spring 2018 March 3, 2019 Lesson 1 CALLED TO HUMILITY AND HOSPITALITY ADULT/YOUTH CHILDREN ADULT/YOUNG ADULT TOPIC: Humility Is Good GENERAL LESSON TITLE: Called to Be Humble for You and Kind YOUTH TOPIC: Sitting with the Lowly CHILDREN’S TOPIC: Dare to Care and Share DEVOTIONAL READING Luke 14:15-24 ADULT/YOUTH BACKGROUND SCRIPTURE: Luke 14:7-14 BACKGROUND SCRIPTURE: Luke 14:7-14 PRINT PASSAGE: Luke 14:7-14 PRINT PASSAGE: Luke 14:7-14 KEY VERSES: Luke 14:13-14a KEY VERSE: Luke 14:11 CHILDREN Luke 14:7-14—KJV Luke 14:7-14—NIV 7 And he put forth a parable to those which 7 When he noticed how the guests picked were bidden, when he marked how they chose the places of honor at the table, he told them this out the chief rooms; saying unto them. -

FOCUS on Matthew a Study Guide for Groups & Individuals

FOCUS ON MATTHEW a study guide for groups & individuals revised edition by Carol Cheney Donahoe Front Matter 1 © 1990, 2001, by Living the Good News All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Formerly published as Focus on the Gospel of Matthew. Living the Good News a division of The Morehouse Group Editorial Offices 600 Grant, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80203 Cover design: Jim Lemons Interior design: Polly Christensen The scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Chris- tian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ, in the USA. Used by permission. ISBN 1-889108-69-3 2 Focus on Matthew Contents Introduction to the Series ................................................. v Introduction to The Gospel of Matthew .......................... ix Matthew 1–4 The Coming of the Messiah ............................................. 1 Matthew 5–7 The Teaching of the Messiah ........................................... 17 Matthew 8:1–11:1 Messianic Ministry and Mission ........................................ 35 Matthew 11:2–12:50 Opposition and Response .................................................. 49 Matthew 13:1-52 Seeing and Hearing the Messiah ....................................... 63 Matthew 13:53–16:20 -

John, the Beloved Disciple

Hugo Bouter JJOOHHNN,, TTHHEE BBEELLOOVVEEDD DDIISSCCIIPPLLEE AS WE FIND HIM IN THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO JOHN New edition — 2004 2 JOHN, THE BELOVED DISCIPLE “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of His disciples, whom Jesus loved”. John 13:23 JOHN, THE BELOVED DISCIPLE 3 CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................ 4 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................... 5 John’s character and calling ......................................... 5 The disciple whom Jesus loved .................................... 6 2. IN THE UPPER ROOM ................................................ 8 Reclining close beside Jesus........................................ 8 The need for cleansing ............................................... 10 3. BY THE CROSS OF JESUS ...................................... 12 The cross and its results............................................. 12 New family ties............................................................ 14 4. BY THE EMPTY TOMB.............................................. 16 Witnesses of Christ’s resurrection .............................. 16 The importance of Christ’s resurrection...................... 18 One spirit with the Lord............................................... 19 5. AT THE SEA OF TIBERIAS (PART 1) ....................... 21 I will make you fishers of men..................................... 21 Resurrection scenes................................................... 22 It is the Lord............................................................... -

BFA JAN 2019.Pdf

January 2019 Orchard Road Presbyterian Church Bible For All (BFA) Studies Overview Our church mission states that ORPC is committed to being a Great Commandment and a Great Commission Church, “To Know Christ and to Make Him Known”. We begin 2019 by reminding ourselves of why we exist as a church. May the Lord grant us fresh eyes and 6 Jan 2019 renewed hearts as we relook the Greatest Matthew 22:34-40 Commandment and the Great Commission in The Greatest Commandment the first and second studies. In the third and fourth studies, we continue exploring the meaning of our mission by considering what it 13 Jan 2019 means to be the kind of disciples and church Matthew 28:16-20 that know Christ and make Christ known. The Great Commission The format for this series has been modified to include the discipleship pointers. However, 20 Jan 2019 please attempt to answer all questions on your Matthew 4:18-22 own before looking at the discipleship pointers. A Certain Kind Of Disciple During the group time, please also set aside time for everyone to share at least one application and pray with one another at the 27 Jan 2019 end of your time together. May the Lord bless Philippians 3:7-11 you in the study and application of His word. Knowing Christ 1 Sermon Date: 6 Jan 2019 Passage: Matthew 22:34-40 Topic: The Greatest Commandment Context Three of this month’s studies are taken from the book of Matthew. Matthew is a book about Christ. It begins with Christ’s genealogy traced back to Abraham, the father of the Jewish nation. -

JESUS: the Calling of the Disciples INTRODUCTION

JESUS: The Calling of the Disciples INTRODUCTION: • The Jesus Series review o Digging in deeper to who Jesus was and what He did Calling of the First Disciples • We are going to look at the callings of The Fishermen (Peter, Andrew, James, and John), and Philp and Andrew. o It is my desire that this is not just a history lesson, but that we will be able to draw some life application from their stories to apply in our lives. § You may be a seeker, a new Christian, or a seasoned saint, but Jesus call to discipleship and deeper discipleship rings on. • Wherever you find yourself today Jesus is calling; are you listening and how will you respond to His call? • Let’s look at what happened in the lives of these men who later would be the men that would turn the world upside down with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The Fishermen • First Encounter with Jesus John 1:35-42 (NKJV) 35 Again, the next day, John stood with two of his disciples. 36 And looking at Jesus as He walked, he said, “Behold the Lamb of God!” 37 The two disciples heard him speak, and they followed Jesus. 38 Then Jesus turned, and seeing them following, said to them, “What do you seek?” They said to Him, “Rabbi” (which is to say, when translated, Teacher), “where are You staying?” 39 He said to them, “Come and see.” They came and saw where He was staying, and remained with Him that day (now it was about the tenth hour). -

087020 Gospelofmark

THE GOSPEL OFMARK AMEN’S STUDY OF CHRISTIAN DISCIPLESHIP A Seven-Session Bible Study for Men by Ronald Edward Peters The Gospel A Men’s Study of Christian Discipleship of Mark A Seven-Session Bible Study for Men Author Ronald Edward Peters Editor Curtis A. Miller Designer Peg Coots Alexander Scripture quotations in this publication are from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. Every effort has been made to trace copyrights on the materials included in this book. If any copyrighted material has nevertheless been included without permission and due acknowledgment, proper credit will be inserted in future printings after notice has been received. © 1998 Christian Education Program Area, Congregational Ministries Division, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Louisville, KY. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any other information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. This book is part of the Men’s Bible Study series produced through the Office for Men’s Ministries of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), a ministry of the General Assembly Council, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Curriculum Publishing Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) 100 Witherspoon Street Louisville, KY 40202-1396 1-800-524-2612 Orders: Ext. 1, Option 1 Curriculum Helpline: Ext. 3 FAX: 502-569-8263 World Wide Web: http://www.pcusa.org/pcusa/currpub Mark CONTENTS Introduction to the Men’s Bible Study ........................................................................................ -

Called Ministry

Sunday School Lesson Mark 1:16-20 by Lorin L. Cranford All rights reserved © Called A copy of this lesson is posted in Adobe pdf format at http://cranfordville.com under Bible Studies in the Bible Study Aids section. A note about the blue, underlined material: These are hyperlinks that allow you to click them on and bring up the specified scripture passage automatically while working inside the pdf file connected to the internet. Just use your web browser’s back arrow or the taskbar to return to the lesson material. ************************************************************************** Quick Links to the Study I. Context II. Message a. Historical a. Andrew and Peter, vv. 6-8 b. Literary b. James and John, vv. 9-20 *************************************************************************** During our history as Baptists, we have given a lot of emphasis to a “called ministry.” The stress has typically been for pastors and other church staff members to have a definite sense of divine calling into vocational Christian ministry. Often one of the scriptural sources for this understanding has been the calling of the disciples by Jesus as described in the four gospels. While making this demand upon the ministers in our ranks, we have not always seen the equal relevancy of the calling of these twelve disciples to our own lives. Somehow, the fact that they left their “jobs” as fishermen in order to follow Jesus puts them in a “clergy” category and out of a “laymen” category. Thus Jesus was calling clergy rather than laymen who are just supposed to sup- port the clergy. This rather interesting reasoning we have inherited from Roman Catholic tradition that has been in place for many centuries.