VOLUMES of N-DIMENSIONAL SPHERES and ELLIPSOIDS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Geometry

Guide Study Georgia End-Of-Course Tests Georgia ANALYTIC GEOMETRY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................5 HOW TO USE THE STUDY GUIDE ................................................................................6 OVERVIEW OF THE EOCT .........................................................................................8 PREPARING FOR THE EOCT ......................................................................................9 Study Skills ........................................................................................................9 Time Management .....................................................................................10 Organization ...............................................................................................10 Active Participation ...................................................................................11 Test-Taking Strategies .....................................................................................11 Suggested Strategies to Prepare for the EOCT ..........................................12 Suggested Strategies the Day before the EOCT ........................................13 Suggested Strategies the Morning of the EOCT ........................................13 Top 10 Suggested Strategies during the EOCT .........................................14 TEST CONTENT ........................................................................................................15 -

General Relativity Fall 2018 Lecture 10: Integration, Einstein-Hilbert Action

General Relativity Fall 2018 Lecture 10: Integration, Einstein-Hilbert action Yacine Ali-Ha¨ımoud (Dated: October 3, 2018) σ σ HW comment: T µν antisym in µν does NOT imply that Tµν is antisym in µν. Volume element { Consider a LICS with primed coordinates. The 4-volume element is dV = d4x0 = 0 0 0 0 dx0 dx1 dx2 dx3 . If we change coordinates, we have 0 ! @xµ d4x0 = det d4x: (1) µ @x Now, the metric components change as 0 0 0 0 @xµ @xν @xµ @xν g = g 0 0 = η 0 0 ; (2) µν @xµ @xν µ ν @xµ @xν µ ν since the metric components are ηµ0ν0 in the LICS. Seing this as a matrix operation and taking the determinant, we find 0 !2 @xµ det(g ) = − det : (3) µν @xµ Hence, we find that the 4-volume element is q 4 p 4 p 4 dV = − det(gµν )d x ≡ −g d x ≡ jgj d x: (4) The integral of a scalar function f is well defined: given any coordinate system (even if only defined locally): Z Z f dV = f pjgj d4x: (5) We can only define the integral of a scalar function. The integral of a vector or tensor field is mean- ingless in curved spacetime. Think of the integral as a sum. To sum vectors, you need them to belong to the same vector space. There is no common vector space in curved spacetime. Only in flat spacetime can we define such integrals. First parallel-transport the vector field to a single point of spacetime (it doesn't matter which one). -

Spheres in Infinite-Dimensional Normed Spaces Are Lipschitz Contractible

PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 88. Number 3, July 1983 SPHERES IN INFINITE-DIMENSIONAL NORMED SPACES ARE LIPSCHITZ CONTRACTIBLE Y. BENYAMINI1 AND Y. STERNFELD Abstract. Let X be an infinite-dimensional normed space. We prove the following: (i) The unit sphere {x G X: || x II = 1} is Lipschitz contractible. (ii) There is a Lipschitz retraction from the unit ball of JConto the unit sphere. (iii) There is a Lipschitz map T of the unit ball into itself without an approximate fixed point, i.e. inffjjc - Tx\\: \\x\\ « 1} > 0. Introduction. Let A be a normed space, and let Bx — {jc G X: \\x\\ < 1} and Sx = {jc G X: || jc || = 1} be its unit ball and unit sphere, respectively. Brouwer's fixed point theorem states that when X is finite dimensional, every continuous self-map of Bx admits a fixed point. Two equivalent formulations of this theorem are the following. 1. There is no continuous retraction from Bx onto Sx. 2. Sx is not contractible, i.e., the identity map on Sx is not homotopic to a constant map. It is well known that none of these three theorems hold in infinite-dimensional spaces (see e.g. [1]). The natural generalization to infinite-dimensional spaces, however, would seem to require the maps to be uniformly-continuous and not merely continuous. Indeed in the finite-dimensional case this condition is automatically satisfied. In this article we show that the above three theorems fail, in the infinite-dimen- sional case, even under the strongest uniform-continuity condition, namely, for maps satisfying a Lipschitz condition. -

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Radar Back-Scattering from Non-Spherical Scatterers

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION NO. 28 STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATION, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION VERA M. BINKS, Director RADAR BACK-SCATTERING FROM NON-SPHERICAL SCATTERERS PART 1 CROSS-SECTIONS OF CONDUCTING PROLATES AND SPHEROIDAL FUNCTIONS PART 11 CROSS-SECTIONS FROM NON-SPHERICAL RAINDROPS BY Prem N. Mathur and Eugam A. Mueller STATE WATER SURVEY DIVISION A. M. BUSWELL, Chief URBANA. ILLINOIS (Printed by authority of State of Illinois} REPORT OF INVESTIGATION NO. 28 1955 STATE OF ILLINOIS WILLIAM G. STRATTON, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION VERA M. BINKS, Director RADAR BACK-SCATTERING FROM NON-SPHERICAL SCATTERERS PART 1 CROSS-SECTIONS OF CONDUCTING PROLATES AND SPHEROIDAL FUNCTIONS PART 11 CROSS-SECTIONS FROM NON-SPHERICAL RAINDROPS BY Prem N. Mathur and Eugene A. Mueller STATE WATER SURVEY DIVISION A. M. BUSWELL, Chief URBANA, ILLINOIS (Printed by authority of State of Illinois) Definitions of Terms Part I semi minor axis of spheroid semi major axis of spheroid wavelength of incident field = a measure of size of particle prolate spheroidal coordinates = eccentricity of ellipse = angular spheroidal functions = Legendse polynomials = expansion coefficients = radial spheroidal functions = spherical Bessel functions = electric field vector = magnetic field vector = back scattering cross section = geometric back scattering cross section Part II = semi minor axis of spheroid = semi major axis of spheroid = Poynting vector = measure of size of spheroid = wavelength of the radiation = back scattering -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

John Ellipsoid 5.1 John Ellipsoid

CSE 599: Interplay between Convex Optimization and Geometry Winter 2018 Lecture 5: John Ellipsoid Lecturer: Yin Tat Lee Disclaimer: Please tell me any mistake you noticed. The algorithm at the end is unpublished. Feel free to contact me for collaboration. 5.1 John Ellipsoid In the last lecture, we discussed that any convex set is very close to anp ellipsoid in probabilistic sense. More precisely, after renormalization by covariance matrix, we have kxk2 = n ± Θ(1) with high probability. In this lecture, we will talk about how convex set is close to an ellipsoid in a strict sense. If the convex set is isotropic, it is close to a sphere as follows: Theorem 5.1.1. Let K be a convex body in Rn in isotropic position. Then, rn + 1 B ⊆ K ⊆ pn(n + 1)B : n n n Roughly speaking, this says that any convex set can be approximated by an ellipsoid by a n factor. This result has a lot of applications. Although the bound is tight, making a body isotropic is pretty time- consuming. In fact, making a body isotropic is the current bottleneck for obtaining faster algorithm for sampling in convex sets. Currently, it can only be done in O∗(n4) membership oracle plus O∗(n5) total time. Problem 5.1.2. Find a faster algorithm to approximate the covariance matrix of a convex set. In this lecture, we consider another popular position of a convex set called John position and its correspond- ing ellipsoid is called John ellipsoid. Definition 5.1.3. Given a convex set K. -

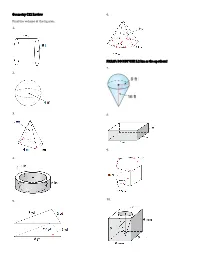

Geometry C12 Review Find the Volume of the Figures. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6

Geometry C12 Review 6. Find the volume of the figures. 1. PREAP: DO NOT USE 5.2 km as the apothem! 7. 2. 3. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 11. 16. 17. 12. 18. 13. 14. 19. 15. 20. 21. A sphere has a volume of 7776π in3. What is the radius 33. Two prisms are similar. The ratio of their volumes is of the sphere? 8:27. The surface area of the smaller prism is 72 in2. Find the surface area of the larger prism. 22a. A sphere has a volume of 36π cm3. What is the radius and diameter of the sphere? 22b. A sphere has a volume of 45 ft3. What is the 34. The prisms are similar. approximate radius of the sphere? a. What is the scale factor? 23. The scale factor (ratio of sides) of two similar solids is b. What is the ratio of surface 3:7. What are the ratios of their surface areas and area? volumes? c. What is the ratio of volume? d. Find the volume of the 24. The scale factor of two similar solids is 12:5. What are smaller prism. the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? 35. The prisms are similar. 25. The scale factor of two similar solids is 6:11. What are a. What is the scale factor? the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? b. What is the ratio of surface area? 26. The ratio of the volumes of two similar solids is c. What is the ratio of 343:2197. What is the scale factor (ratio of sides)? volume? d. -

Projective Geometry: a Short Introduction

Projective Geometry: A Short Introduction Lecture Notes Edmond Boyer Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Objective . .2 1.2 Historical Background . .3 1.3 Bibliography . .4 2 Projective Spaces 5 2.1 Definitions . .5 2.2 Properties . .8 2.3 The hyperplane at infinity . 12 3 The projective line 13 3.1 Introduction . 13 3.2 Projective transformation of P1 ................... 14 3.3 The cross-ratio . 14 4 The projective plane 17 4.1 Points and lines . 17 4.2 Line at infinity . 18 4.3 Homographies . 19 4.4 Conics . 20 4.5 Affine transformations . 22 4.6 Euclidean transformations . 22 4.7 Particular transformations . 24 4.8 Transformation hierarchy . 25 Grenoble Universities 1 Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Objective The objective of this course is to give basic notions and intuitions on projective geometry. The interest of projective geometry arises in several visual comput- ing domains, in particular computer vision modelling and computer graphics. It provides a mathematical formalism to describe the geometry of cameras and the associated transformations, hence enabling the design of computational ap- proaches that manipulates 2D projections of 3D objects. In that respect, a fundamental aspect is the fact that objects at infinity can be represented and manipulated with projective geometry and this in contrast to the Euclidean geometry. This allows perspective deformations to be represented as projective transformations. Figure 1.1: Example of perspective deformation or 2D projective transforma- tion. Another argument is that Euclidean geometry is sometimes difficult to use in algorithms, with particular cases arising from non-generic situations (e.g. -

Automatic Estimation of Sphere Centers from Images of Calibrated Cameras

Automatic Estimation of Sphere Centers from Images of Calibrated Cameras Levente Hajder 1 , Tekla Toth´ 1 and Zoltan´ Pusztai 1 1Department of Algorithms and Their Applications, Eotv¨ os¨ Lorand´ University, Pazm´ any´ Peter´ stny. 1/C, Budapest, Hungary, H-1117 fhajder,tekla.toth,[email protected] Keywords: Ellipse Detection, Spatial Estimation, Calibrated Camera, 3D Computer Vision Abstract: Calibration of devices with different modalities is a key problem in robotic vision. Regular spatial objects, such as planes, are frequently used for this task. This paper deals with the automatic detection of ellipses in camera images, as well as to estimate the 3D position of the spheres corresponding to the detected 2D ellipses. We propose two novel methods to (i) detect an ellipse in camera images and (ii) estimate the spatial location of the corresponding sphere if its size is known. The algorithms are tested both quantitatively and qualitatively. They are applied for calibrating the sensor system of autonomous cars equipped with digital cameras, depth sensors and LiDAR devices. 1 INTRODUCTION putation and memory costs. Probabilistic Hough Transform (PHT) is a variant of the classical HT: it Ellipse fitting in images has been a long researched randomly selects a small subset of the edge points problem in computer vision for many decades (Prof- which is used as input for HT (Kiryati et al., 1991). fitt, 1982). Ellipses can be used for camera calibra- The 5D parameter space can be divided into two tion (Ji and Hu, 2001; Heikkila, 2000), estimating the pieces. First, the ellipse center is estimated, then the position of parts in an assembly system (Shin et al., remaining three parameters are found in the second 2011) or for defect detection in printed circuit boards stage (Yuen et al., 1989; Tsuji and Matsumoto, 1978).