Gendering Elizabeth I Through the Tilbury Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leicester Beer Festival 2015

Leicester Beer Festival 2015 www.leicestercamra.org.uk Facebook/leicestercamra @LeicesterCAMRA 11 - 14 MARCH CHAROTAR PATIDAR SAMAJ, BAY STREET, LEICESTER LEICESTER BEER FESTIVAL 2015 1 TIGER BEST BITTER www.everards.co.uk @EverardsTiger facebook.com/everards LEICESTER BEER FESTIVAL 2015 2 Southwell Folk Fest A5 ad Portrait.indd 1 16/05/2014 16:25 Chairman’s Welcome At last, it’s that time of the year again and I would like to welcome you to the Leicester CAMRA Beer Festival 2015. This is the sixteenth since our re-launch in 1999 following a ten-year absence. We are delighted to be back at the Charotar Patidar Samaj for the fifteenth time. As always we are showcasing the brewing expertise of our Leicestershire and Rutland breweries on our LocAle bars, we also feature a selection of breweries within 25 miles as the crow flies from the festival site giving an amazing 40 breweries within the area to choose from. This year we have divided the servery up into six distinct bars and colour-coded them (see p 15 for details). We have numbered the beers to make it easier to remember what to order at the bar. Our festival is one of many that play a major role not just as fund raising, but also to keep people informed about CAMRA’s work and the vast range of beers that are now available to the consumer. This continuous background work nationwide has doubtless helped change attitudes towards real ale. Our theme this year is XV, a full explanation of which appears in the article on page 9. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/02 Dorothea Flothow 5 Unheroic and Yet Charming – Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays It has been claimed repeatedly that unlike previ- MacDonald’s Not About Heroes (1982) show ous times, ours is a post-heroic age (Immer and the impossibility of heroism in modern warfare. van Marwyck 11). Thus, we also fi nd it diffi cult In recent years, a series of bio-dramas featuring to revere the heroes and heroines of the past. artists, amongst them Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus In deed, when examining historical television se- (1979) and Sebastian Barry’s Andersen’s En- ries, such as Blackadder, it is obvious how the glish (2010), have cut their “artist-hero” (Huber champions of English imperial history are lam- and Middeke 134) down to size by emphasizing pooned and “debunked” – in Blackadder II, Eliz- the clash between personal action and high- abeth I is depicted as “Queenie”, an ill-tempered, mind ed artistic idealism. selfi sh “spoiled child” (Latham 217); her immor- tal “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” becomes The debunking of great historical fi gures in re- part of a drunken evening with her favourites cent drama is often interpreted as resulting par- (Epi sode 5, “Beer”). In Blackadder the Third, ticularly from a postmodern infl uence.3 Thus, as Horatio Nelson’s most famous words, “England Martin Middeke explains: “Postmodernism sets expects that every man will do his duty”, are triv- out to challenge the occidental idea of enlighten- ialized to “England knows Lady Hamilton is a ment and, especially, the cognitive and episte- virgin” (Episode 2, “Ink and Incapability”). -

Seminary Studies

ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES VOLUME VI JANUARI 1968 NUMBER I CONTENTS Heimmerly-Dupuy, Daniel, Some Observations on the Assyro- Babylonian and Sumerian Flood Stories Hasel, Gerhard F., Sabbatarian Anabaptists of the Sixteenth Century: Part II 19 Horn, Siegfried H., Where and When was the Aramaic Saqqara Papyrus Written ? 29 Lewis, Richard B., Ignatius and the "Lord's Day" 46 Neuffer, Julia, The Accession of Artaxerxes I 6o Specht, Walter F., The Use of Italics in English Versions of the New Testament 88 Book Reviews iio ANDREWS UNIVERSITY BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICHIGAN 49104, USA ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES The Journal of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary of Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan SIEGFRIED H. HORN Editor EARLE HILGERT KENNETH A. STRAND Associate Editors LEONA G. RUNNING Editorial Assistant SAKAE Kos() Book Review Editor ROY E. BRANSON Circulation Manager ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES publishes papers and short notes in English, French and German on the follow- ing subjects: Biblical linguistics and its cognates, textual criticism, exegesis, Biblical archaeology and geography, an- cient history, church history, theology, philosophy of religion, ethics and comparative religions. The opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors. ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES is published in January and July of each year. The annual subscription rate is $4.00. Payments are to be made to Andrews University Seminary Studies, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104, USA. Subscribers should give full name and postal address when paying their subscriptions and should send notice of change of address at least five weeks before it is to take effect; the old as well as the new address must be given. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Evangelism and Capitalism: a Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 6-2018 Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship Jason Paul Clark George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Jason Paul, "Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship" (2018). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 132. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVANGELICALISM AND CAPITALISM A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Paul Clark Middlesex University Supervised at London School of Theology June 2018 Abstract Jason Paul Clark, “Evangelicalism and Capitalism: A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship.” Doctor of Philosophy, Middlesex University, 2018. No sustained examination and diagnosis of problems inherent to the relationship of Evangeli- calism with capitalism currently exists. Where assessments of the relationship have been un- dertaken, they are often built upon a lack of understanding of Evangelicalism, and an uncritical reliance both on Max Weber’s Protestant Work Ethic and on David Bebbington’s Quadrilateral of Evangelical priorities. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25Years of Great Taste

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25years of Great Taste MEMORIES FOR SALE! Be sure to pick up your copy of the limited edition full-color book, The Great Taste of the Midwest: Celebrating 25 Years, while you’re here today. You’ll love reliving each and every year of the festi- val in pictures, stories, stats, and more. Books are available TODAY at the festival souve- nir sales tent, and near the front gate. They will be available online, sometime after the festival, at the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild website, http://mhtg.org. WelcOMe frOM the PresIdent elcome to the Great taste of the midwest! this year we are celebrating our 25th year, making this the second longest running beer festival in the country! in celebration of our silver anniversary, we are releasing the Great taste of the midwest: celebrating 25 Years, a book that chronicles the creation of the festival in 1987W and how it has changed since. the book is available for $25 at the merchandise tent, and will also be available by the front gate both before and after the event. in the forward to the book, Bill rogers, our festival chairman, talks about the parallel growth of the craft beer industry and our festival, which has allowed us to grow to hosting 124 breweries this year, an awesome statistic in that they all come from the midwest. we are also coming close to maxing out the capacity of the real ale tent with around 70 cask-conditioned beers! someone recently asked me if i felt that the event comes off by the seat of our pants, because sometimes during our planning meetings it feels that way. -

DICKENS on SCREEN, BFI Southbank's Unprecedented

PRESS RELEASE 12/08 DICKENS ON SCREEN AT BFI SOUTHBANK IN FEBRUARY AND MARCH 2012 DICKENS ON SCREEN, BFI Southbank’s unprecedented retrospective of film and TV adaptations, moves into February and March and continues to explore how the work of one of Britain’s best loved storytellers has been adapted and interpreted for the big and small screens – offering the largest retrospective of Dickens on film and television ever staged. February 7 marks the 200th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ birth and BFI Southbank will host a celebratory evening in partnership with Film London and The British Council featuring the world premiere of Chris Newby’s Dickens in London, the innovative and highly distinctive adaptation of five radio plays by Michael Eaton that incorporates animation, puppetry and contemporary footage, and a Neil Brand score. The day will also feature three newly commissioned short films inspired by the man himself. Further highlights in February include a special presentation of Christine Edzard’s epic film version of Little Dorrit (1988) that will reunite some of the cast and crew members including Derek Jacobi, a complete screening of the rarely seen 1960 BBC production of Barnaby Rudge, as well as day long screenings of the definitive productions of Hard Times (1977) and Martin Chuzzlewit (1994). In addition, there will be the unique opportunity to experience all eight hours of the RSC’s extraordinary 1982 production of Nicholas Nickleby, including a panel discussion with directors Trevor Nunn and John Caird, actor David Threlfall and its adaptor, David Edgar. Saving some of the best for last, the season concludes in March with a beautiful new restoration of the very rare Nordisk version of Our Mutual Friend (1921) and a two-part programme of vintage, American TV adaptations of Dickens - most of which have never been screened in this country before and feature legendary Hollywood stars. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

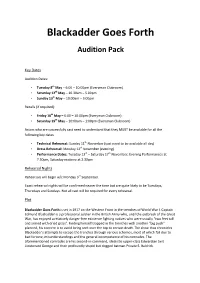

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

VPI June 2016

c/o sur la Croix 160, CH - 1020 Renens. www.villageplayers.ch Payments: CCP 10-203 65-1 IBAN: CH71 0900 0000 1002 0365 1 Village Players’ Information (VPI) June 2016 NEXT CLUBNIGHT: VILLAGE PLAYERS’ Annual General Meeting !!!! COME AND FILL THESE SEATS !!!! Thursday 16th June, 2016 At 20h00 Doors open at 19h15 Bar open 19h30 CPO - Centre Pluriculturel d’Ouchy Beau-Rivage 2, 1006 Lausanne PLEASE NOTE IN YOUR DIARIES – AND TELL YOUR FRIENDS AND FELLOW MEMBERS Come and have your say in the running of the club and our activities, and cast your vote for the new Committee. Of the present Committee, the following are willing to stand for (re)election for the following posts: Production Coordinator Daniel Gardini Events Coordinator Mary Couper Secretary Colin Gamage Treasurer Derek Betson Publicity Manager Susan Morris Membership Secretary Dorothy Brooks Technical Manager Ian Griffiths At the moment we have the proposal of Chris Hemmens for the post of Chairman but do not have candidates for the posts of Administrative Director and Business Manager. So before, or latest at, the AGM we will be looking for volunteers to come forward to fill these positions. Brief descriptions of these posts are: ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR: Coordinates the running of the Society, guarantees its efficient administration, assists and deputises for the Chairman. BUSINESS MANAGER: Responsible for forward planning, negotiation for hire of theatres, rooms for productions and events; liaison with appropriate authorities for services, purchase of tickets, front of house, payment of dues and performance rights. THIS IS A VERY IMPORTANT MEETING – WE NEED YOU ALL TO COME ALONG.