Mt Ararat Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Mountains of Ararat

In the Mountains of Ararat By Mary L. Doerflein Copyright: 2010 Pending #: [1-367414787] [Thread ID: 1-62UTQ1] Table of Adventures I Introduction 3 Expedition Summaries 4 Arrival of the raven 11 Anchors 13 Cultural Connections 21 II Chronology and Commentaries 28 Ascent of the Flood 29 Descent of the Flood 35 Acknowledgements 42 Persons Unknown 42 Persons Known 43 III Bibliographies 44 Copyright©2010 Mary Doerflein 2 From the Mountains of Ararat Photograph by Mustafa Arsin INTRODUCTION In peering through Noah’s window, almost “from the top,” it is iced and fossilized, but an attempt has been made to melt some of the historical impasses with: (I) expedition summaries by our tour guide, the raven; (II) a chronology of Chapters 7 and 8 of Genesis merging a minimum of three authors (doublets, J and P, and the mystery redactor, R); acknowledgment of the Gilgamesh and Simmons tablet epics, the above sources interspersed with relevant comments and recent theories; then finally, (III) an addenda of bibliographies that give an opportunity for you to pick through and spade into the silt of ambiguity. From Luke 1:1 “Forasmuch as many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us, even as they delivered them unto us, which from the beginning were eyewitnesses, and ministers of the word; it seemed good to me also, having had perfect understanding of all things from the very first, to write to you . “ As it now seems good to me, even without perfect understanding, to write to you a declaration of recent treks to find Noah’s ark, most surely believed . -

In Search of Noah's Ark

IN SEARCH OF NOAH'S ARK History does not care how events happen, it just takes the side of those who do great things and achieve great goals. At the time of writing, this scientific work I was guided by the only desire to enrich our history, to fill the gaps in it, to make it more open to understanding others, but not in any way to harm the established historical order in it. The constant desire to find God, to explain the inexplicable, the deification of the forces of nature, the desire to comprehend the incomprehensible at all times inherent in man. Studying the world around us, people learn more and more new things, and as a result of this there is a need to preserve and transmit information, whether it is in visual form, written or verbal in legends or myths. For example, in religious texts. "Noah did everything God commanded him to do. Upon completion of the construction, God told Noah to enter the ark with his sons and wife, and with the wives of his sons, and to bring also into the ark of all the animals in pairs, that they might live. And take for yourself of all food which is necessary themselves and for animals. Then the ark was shut down by God. Seven days later (in the second month, the seventeenth [27th-according to the translation of the Septuagint] day) the rain poured out on the earth, and the flood lasted forty days and forty nights, and the water multiplied, and lifted up the ark, and it rose above the earth and floated on the surface of the waters. -

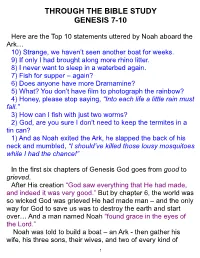

Noah Aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, We Haven’T Seen Another Boat for Weeks

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY GENESIS 7-10 Here are the Top 10 statements uttered by Noah aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, we haven’t seen another boat for weeks. 9) If only I had brought along more rhino litter. 8) I never want to sleep in a waterbed again. 7) Fish for supper – again? 6) Does anyone have more Dramamine? 5) What? You don’t have film to photograph the rainbow? 4) Honey, please stop saying, “Into each life a little rain must fall.” 3) How can I fish with just two worms? 2) God, are you sure I don’t need to keep the termites in a tin can? 1) And as Noah exited the Ark, he slapped the back of his neck and mumbled, “I should’ve killed those lousy mosquitoes while I had the chance!” In the first six chapters of Genesis God goes from good to grieved. After His creation “God saw everything that He had made, and indeed it was very good.” But by chapter 6, the world was so wicked God was grieved He had made man – and the only way for God to save us was to destroy the earth and start over… And a man named Noah “found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Noah was told to build a boat – an Ark - then gather his wife, his three sons, their wives, and two of every kind of [1 animal on the earth. Noah was obedient… Which is where we pick it up tonight, chapter 7, “Then the LORD said to Noah, "Come into the ark, you and all your household, because I have seen that you are righteous before Me in this generation.” What a moving scene… When it’s time to board the Ark, God doesn’t tell Noah to go onto the ark, but to “come into the ark” – the implication is that God is onboard waiting for Noah. -

Noah and the Flood God Used Water in a Flood to Drown Genesis 6:1–9:17 Sinful Mankind

Everyday Family Page Old Testament 1 FAITH Law/Gospel Noah and the Flood God used water in a flood to drown Genesis 6:1–9:17 sinful mankind. In Baptism, God uses water to drown my sins, enesis 6 reports a distorted view of life that developed because of sin. granting me eternal life through G God-believing sons of Adam’s tribe married women from Cain’s tribe, His Son, Jesus. valuing physical attractiveness and strength over faith in God. This showed their children that physical aspects mattered most and gave the impression that faith was optional. Bible Words The Lord saw the resulting wickedness, evil intentions, corruption, and In the days of Noah, while the violence; it grieved His heart. Regretting He made humans, the Lord decid- ark was being prepared, in which ed to wipe out all living creatures. Only Noah walked with the Lord (6:8–9). a few . were brought safely through water. Baptism . now By faith, Noah, his wife, three sons, and their wives built the ark as saves you . through the resur- God said. Later, God brought animals and birds to the ark, to keep them rection of Jesus Christ. alive and safe while God destroyed the world through the flood. 1 Peter 3:20–21 Seven days after they entered the ark, rain began to fall; it fell for forty days. In addition, “fountains of the great deep burst forth, and the windows of the heavens were opened” (7:11–12). Over twenty feet of water Fun Facts covered the highest mountains. -

Who Is the Daughter of Babylon?

WHO IS THE DAUGHTER OF BABYLON? ● Babylon was initially a minor city-state, and controlled little surrounding territory; its first four Amorite rulers did not assume the title of king. The older and more powerful states of Assyria, Elam, Isin, and Larsa overshadowed Babylon until it became the capital of Hammurabi's short-lived empire about a century later. Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BC) is famous for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi. He conquered all of the cities and city states of southern Mesopotamia, including Isin, Larsa, Ur, Uruk, Nippur, Lagash, Eridu, Kish, Adab, Eshnunna, Akshak, Akkad, Shuruppak, Bad-tibira, Sippar, and Girsu, coalescing them into one kingdom, ruled from Babylon. Hammurabi also invaded and conquered Elam to the east, and the kingdoms of Mari and Ebla to the northwest. After a protracted struggle with the powerful Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan of the Old Assyrian Empire, he forced his successor to pay tribute late in his reign, spreading Babylonian power to Assyria's Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor. After the reign of Hammurabi, the whole of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, whereas the north had already coalesced centuries before into Assyria. From this time, Babylon supplanted Nippur and Eridu as the major religious centers of southern Mesopotamia. Hammurabi's empire destabilized after his death. Assyrians defeated and drove out the Babylonians and Amorites. The far south of Mesopotamia broke away, forming the native Sealand Dynasty, and the Elamites appropriated territory in eastern Mesopotamia. The Amorite dynasty remained in power in Babylon, which again became a small city-state. -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

The Great Flood of Noah's Day, Part 2

The Books of Moses Fact or Fiction? Session 6 The Great Flood in Noah’s Day Part 2 Bruce Armstrong The Great Flood in Noah’s Day, Part 2 Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................1 Jehovah’s Promise...............................................................................1 Instructions to Noah............................................................................3 God’s Covenant With All Creatures....................................................4 Various Great Flood Issues..................................................................6 Local or Global Flood?...................................................................6 Where is All the Water?..................................................................8 World-wide Flood Stories...............................................................8 Where did the Ark Land?................................................................9 Animal Migrations........................................................................15 Was the Great Ice Age a Result of the Great Flood?....................16 Human Lifespans..........................................................................17 How Many People Died in the Great Flood?................................19 Who are the Neanderthals?...........................................................21 Who are the Cavemen?.................................................................22 Genetic Evidence for Noah’s Family?..........................................22 -

Seven Mountains to Aratta

Seven Mountains to Aratta Searching for Noah's Ark in Iran B.J. Corbin Copyright ©2014 by B.J. Corbin. All rights reserved. 1st Edition Last edited: August 30, 2015 Website: www.bjcorbin.com Follow-up book to The Explorers of Ararat: And the Search for Noah’s Ark by B.J. Corbin and Rex Geissler available at www.noahsarksearch.com. Introduction (draft) The basic premise of the book is this... could there be a relationship between the Biblical "mountains of Ararat" as the landing site of Noah's Ark and the mythical mountain of Aratta as described in ancient Sumerian literature? Both the Biblical Flood mentioned in Genesis chapters 6-8 and The Epic of Gilgamesh in tablet 11 (and other Sumerian texts), seem to be drawing from the same historical flood event. Probable Noah’s Ark landing sites were initially filtered by targeting "holy mountains" in Turkey and Iran. The thinking here is that something as important and significant as where Noah's Ark landed and human civilization started (again) would permeate throughout history. Almost every ancient culture maintains a flood legend. In Turkey, both Ararat and Cudi are considered holy mountains. Generally, Christians hold Mount Ararat in Turkey as the traditional landing site of Noah's Ark, while Muslims adhering to the Koran believe that Mount Cudi (pronounced Judi in Turkish) in southern Turkey is the location where Noah's Ark landed. In Iran, both Damavand and Alvand are considered holy mountains. Comparing the geography of the 4 holy mountains, Alvand best fits the description in Genesis 11:2 of people moving “from the east” into Shinar, if one supports that definition of the verse. -

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree doctor of philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By J. H. Price, M.A., B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Samuel A. Meier, Advisor Daniel Frank Carolina López-Ruiz Bill T. Arnold Copyright by J. H. Price 2015 Abstract In the ancient world, kings were a common subject of literary activity, as they played significant social, economic, and religious roles in the ancient Near East. Unsurprisingly, the praiseworthy deeds of kings were often memorialized in ancient literature. However, in some texts kings were remembered for criminal acts that brought punishment from the god(s). From these documents, which date from the second to the first millennium BCE, we learn that royal acts of sacrilege were believed to have altered the fate of the offending king, his people, or his nation. These chastised rulers are the subject of this this dissertation. In the pages that follow, the violations committed by these rulers are collected, explained, and compared, as are the divine punishments that resulted from royal sacrilege. Though attestations are concentrated in the Hebrew Bible and Mesopotamian literature, the very fact that the chastised ruler type also surfaces in Ugaritic, Hittite, and Northwest Semitic texts suggests that the concept was an integral part of ancient near eastern kingship ideologies. Thus, this dissertation will also explain the relationship between kings and gods and the unifying aspect of kingship that gave rise to the chastised ruler concept across the ancient Near East. -

The Geography of Genesis 8:4

JOURNAL OF CREATION 30(1) 2016 || VIEWPOINT The Geography of Genesis 8:4 Bill Crouse The author of Genesis informs us that the Ark of Noah landed “in the mountains of Ararat”. While this is a general area, it refers to a real location. The key to pinpointing this geographic area is to ask where would the original readers of Genesis have understood it to have been. Geographical and historical studies lead us to conclude that the writer was referring to the mountainous region to the south of Lake Van and north of the historic kingdom of Assyria. It therefore cannot refer to the singular Mt Ararat in north-eastern Turkey as is commonly presumed. n Genesis 8:4 the Bible not only gives us a precise date the name of a unified state which covered a much Ifor the landing of the Ark but an actual geographic locale larger expanse.” 5 for its final berth.1 Given this attention to detail, it would Piotrovsky also believes that it is an Assyrian word. He seem expedient to assume the author wants us to see this believes it “had no ethnic significance but was most probably event as one occurring in space-time history. In the most a descriptive term (perhaps meaning ‘the mountainous important voyage in history, one that transports a remnant country’)” .6 of human and animal life from the antediluvian to the post- In their own literature, they refer to themselves as diluvian world, the author gives a fairly precise location as to the Biainili and designate their kingdom Nairi. -

The Use of Apologetics in the Book of Isaiah

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY THE USE OF APOLOGETICS IN THE BOOK OF ISAIAH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO DR. RANDALL PRICE AND COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE PHD IN THEOLOGY AND APOLOGETICS LIBERTY UNIVERSITY RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY BY DANIEL SLOAN LYNCHBURG, VA Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Sloan All Rights Reserved ii LIBERTY UNIVERSITY RAWLINGS SCHOOL OF DIVINITY DISSERTATION APPROVAL SHEET ___________________________ J. RANDALL PRICE Ph.D. CHAIR ________________________ EDWARD E. HINDSON Th.D. FIRST READER _______________________ MARK ALLEN Ph.D. SECOND READER iii ABSTRACT Isaiah used apologetics in three distinct areas: Yahweh’s creation and sovereign control (Past), Yahweh’s divine intervention in delivering Judah (present) and Yahweh as the controller of the future (Immediate, Exilic, Messianic and eschatological) to argue that Yahweh was the one true God, unique and superior to all pagan deities, to both his contemporary audience and to future generations. In chapter one, the research questions are addressed, a literary review is presented, and the methodology of the dissertation is given. In chapter two, the dissertation addresses how the book of Isaiah argues apologetically that Yahweh is the Creator and therefore is incomparable. In chapter three, the dissertation presents how the book of Isaiah argues apologetically that Yahweh’s ability to divinely intervene in history shows His incomparability. In chapter four, the dissertation addresses how the book of Isaiah argues apologetically that Yahweh can know and predict the future and therefore is incomparable. A conclusion is given in which the theological and apologetic implications are addressed and further areas of research is identified. -

Apkallu Certain Texts Are Attributed to Sages, No- Tably Two Medical Texts and a Hymn (REINER I

Iconography of Deities and Demons: Electronic Pre-Publication 1/7 Last Revision: 10 March 2011 Apkallu Certain texts are attributed to sages, no- tably two medical texts and a hymn (REINER I. Introduction. Mesopotamian semi- 1961), the Myth of Etana, the Sumerian divine figure. A Babylonian tradition related Tale of Three Ox-drivers, the Babylonian by Berossos in the 3rd cent. (BURSTEIN Theodicy, and the astrological series UD.SAR 1978: 13f) describes a creature called Oan- Anum Enlila. In Assyrian tradition the sages nes that rose up out of the Red Sea in the guarded the Tablet of Destinies for the god first year of man’s history. His entire body →Nabu, patron of scribes. This information was that of a fish, but he had another head, gives a possible link with the composite presumably human, and feet like a man as monsters in the tradition of the Babylonian well as a fish tail. He taught men to write, as Epic of Creation, which centers on control well as many other arts, crafts, and institu- of the Tablet of Destinies. Such a link tions of civilization. He taught them to build would explain the scene that puts phenotype cities and temples, to have laws, to till the 1 (see § II.1) with composite monsters who land, and to harvest crops. At sunset he fight as archers (24), and phenotype 2 returned to the sea. Later there were other (see § II.2) with mermen (44*, 51) and similar creatures who appeared on the earth. composite monsters (50*). However, in These were the sages.