To Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Witney Ùيلم قائمة (ÙÙŠÙ

William Witney ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… وغراÙÙ ŠØ§) Tarzan's Jungle Rebellion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tarzan%27s-jungle-rebellion-10378279/actors The Lone Ranger https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lone-ranger-10381565/actors Trail of Robin Hood https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/trail-of-robin-hood-10514598/actors Twilight in the Sierras https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twilight-in-the-sierras-10523903/actors Young and Wild https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/young-and-wild-14646225/actors South Pacific Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-pacific-trail-15628967/actors Border Saddlemates https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/border-saddlemates-15629248/actors Old Oklahoma Plains https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-oklahoma-plains-15629665/actors Iron Mountain Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/iron-mountain-trail-15631261/actors Old Overland Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-overland-trail-15631742/actors Shadows of Tombstone https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shadows-of-tombstone-15632301/actors Down Laredo Way https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/down-laredo-way-15632508/actors Stranger at My Door https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stranger-at-my-door-15650958/actors Adventures of Captain Marvel https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adventures-of-captain-marvel-1607114/actors The Last Musketeer https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-musketeer-16614372/actors The Golden Stallion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-golden-stallion-17060642/actors Outlaws of Pine Ridge https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/outlaws-of-pine-ridge-20949926/actors The Adventures of Dr. -

Festival of ABC 2018 Brochure

NOVEMBER 11-18, 2018 Alexandra Silber Norman Eisen Allison Yarrow Dan Richard Abrams Kind www.katzjcc.org/abcfest Brad Meltzer SUNDAY NOV 11 David E. Sanger “…A reader finishes this The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, book fully understanding and Fear in the Cyber Age why cyberwar has moved 10:00 am • Lahn Social Hall rapidly to the top of Sponsored by SHM Financial America’s official list of national security threats. From the White House situation room to the dens And why, for the first time of Chinese government hackers to the boardrooms of Silicon Valley, David Sanger, national in three generations, this security correspondent for the New York Times and CNN reporter, reveals a world coming nation’s power in the world face-to-face with the perils of technological revolution. The Perfect Weapon is the dramatic is seriously threatened.” story of how great and small powers alike slipped into a new era of constant sabotage, misinformation, and fear, in which everyone is a target. —THE WASHINGTON POST $20 JCC Member / $25 Guest Community-Wide Kristallnacht Observance FREE!FREE! Michael Ross From Broken Glass: My Story of Finding Hope in Hitler’s Death Camps to Inspire a New Generation 11:30 am • Lahn Social Hall Sponsored by Valerie & David Gladfelter Endowment Fund of the JCF, Inc. From the survivor of 10 Nazi concentration camps, this inspiring memoir tells a story about finding strength in the face of despair. After enduring inconceivable cruelty as well as receiving compassion from caring fellow prisoners, Steve Ross believes the human spirit is capable of rising above even the bleakest circumstances. -

Before the Supreme Court of Missouri

Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI December 20, 2013 10:28 AM Before The Supreme Court of Missouri ________________________ No. SC 93640 DORIS DEMORE, Appellant and Cross Respondent, v. AMERICA FIRST INSURANCE COMPANY, Respondent and Cross Appellant. ________________________ APPEAL FROM A FINAL AWARD OF THE LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION OF MISSOURI SUBSTITUTE BRIEF OF THE APPELLANT AND CROSS RESPONDENT DORIS DEMORE ________________________ NEALE & NEWMAN, L.L.P. Patrick J. Platter, #29822 Britton D. Jobe, #62084 Post Office Box 10327 Springfield, MO 65808 Telephone: (417) 882-9090 Fax: (417) 882-2529 Attorneys for the Appellant-Cross And Respondent Doris Demore Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI December 20, 2013 10:28 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities ........................................................................................................... v Jurisdictional Statement ……………………………………………………………... ... 1 Statement of Facts ............................................................................................................. 2 The Businesses ........................................................................................................ 2 Vandalism and Burglaries ..................................................................................... 4 The Accident .......................................................................................................... 6 Doris Demore’s Injuries ........................................................................................ -

Michael Pye Phd Thesis

IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAR? SOVIET-IRANIAN RELATIONS DURING THE REIGN OF MOHAMMAD REZA PAHLAVI Michael Pye A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/9501 This item is protected by original copyright IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAR? SOVIET-IRANIAN RELATIONS DURING THE REIGN OF MOHAMMAD REZA PAHLAVI CANDIDATE: MICHAEL PYE DEGREE: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DATE OF SUBMISSION: 26TH OF MAY 2015 1 ABSTRACT The question mark of the project's title alludes to a critical reexamination of Soviet- Iranian relations during the period and aims to offer an original contribution to scholarship in the field by exploring an aspect of Pahlavi foreign relations that lacks any detailed treatment in the literature presently available. In pursuit of this goal, research has been concentrated on recently-released western archival documentation, the Iranian Studies collection held at the University of St Andrews, and similarly materials from the Russian Federal Archive for Foreign Relations, to which the author was granted access, including ambassadorial papers relating to the premiership of Mohammad Mosaddeq. As far as can be ascertained, the majority of the Russian archival evidence presented in the dissertation has not been previously been utilised by any Western-based scholar. At core, the thesis argues that the trajectory of Pahlavi foreign relations specifically (and to a certain degree Mohammad Reza's regency more broadly) owed principally to a deeply-rooted belief in, and perceived necessity to guard against, the Soviet Union's (and Russia's) historical 'objectives' vis-à-vis Iran. -

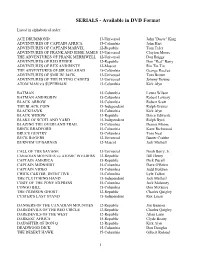

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Filming Politics: Communism and the Portrayal of the Working Class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2007 Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946 Khouri, Malek University of Calgary Press Khouri, M. "Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946". Series: Cinemas off centre series; 1912-3094: No. 1. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49340 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com FILMING POLITICS: COMMUNISM AND THE PORTRAYAL OF THE WORKING CLASS AT THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA, 1939–46 by Malek Khouri ISBN 978-1-55238-670-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content Company & Financial Congressional Transcripts (GROUP FILE Food and Drug Administration Espicom Company Reports (SELECTED ONLY) Veterinarian Newsletter MATERIAL) (GROUP FILE ONLY) Election Weekly (GROUP FILE ONLY) Health and Human Services Department Legal FDCH Transcripts of Political Events Military Review American Bar Association Publications (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Endowment for the Humanities ABA All Journals (GROUP FILE ONLY) General Accounting Office Reports "Humanities" Magazine ABA Antitrust Law Journal (GROUP FILE (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and ONLY) Government Publications (GROUP FILE Alcoholism's Alcohol Research & ABA Banking Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY): Health ONLY) Agriculture Department's Economic National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA ABA Business Lawyer (GROUP FILE Research Service Agricultural Outlook Notes ONLY) Air and Space Power Journal National Institutes of Health ABA Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY) Centers for Disease Control and Naval War College Review ABA Legal Economics from 1/82 & Law Prevention Public Health and the Environment Practice from 1/90 (GROUP FILE ONLY) CIA World Factbook SEC News Digest ABA Quarterly Tax Lawyer (GROUP FILE Customs and Border Protection Today State Department ONLY) Department of Energy Documents The Third Branch ABA The International Lawyer (GROUP Department of Energy's Alternative Fuel U.S. Department of Agricultural FILE ONLY) News Research ABA Tort and Insurance Law Journal Department of Homeland Security U.S. Department of Justice's -

HUNGARIAN STUDIES 17. No. 1. Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai

Volume 17 Number 1 Hungarian Chair Symposium, March 29, 2003, Bloomington: Between East and West: Hungarian Foreign Policy in the 20th Century Thomas Cooper: Mimesis of Consciousness in the Fiction of Zsigmond Kemény Pál Deréky: Eigenkultur - Fremdkultur. Zivilisationskritisch fundierte Selbstfindung in den literarischen Reisebeschreibungen der Aktivisten Robert Müller und Lajos Kassák HUNGARIAN STUDIES a Journal of the International Association for Hungarian Studies (Nemzetközi Magyarságtudományi Társaság) Hungarian Studies appears twice a year. It publishes original essays - written in English, French and German - dealing with aspects of the Hungarian past and present. Multidisciplinary in its approach, it is an international forum of literary, philological, historical and related studies. Each issue contains about 160 pages and will occasionally include illustrations. All manuscripts, books and other publications for review should be sent to the editorial address. Only original papers will be published and a copy of the Publishing Agreement will be sent to the authors of papers accepted for publication. Manuscripts will be processed only after receiving the signed copy of the agreement. Hungarian Studies is published by AKADÉMIAI KIADÓ H-1117 Budapest, Prielle Kornélia u. 19. Homepage: www.akkrt.hu/journals/hstud Order should be addressed to AKADÉMIAI KIADÓ, H-1519 Budapest, P.O. Box 245, Fax: (36-1)464-8221, E-mail: [email protected] Subscription price for Volume 17 (2003) in 2 issues EUR/USD 148.00, including online and normal postage; airmail delivery EUR/USD 20.00 Editorial address H-1067 Budapest, Teréz körút 13. II/205-207. Telephone/Fax: (36-1) 321-4407 Mailing address: H-1250 Budapest, P.O. -

Canadion Political Parties: Origin, Character, Impact (Scarborough: Prentice-Hail, 1975), 30

OUTSIDELOOKING IN: A STUDYOF CANADIANFRINGE PARTIES by Myrna J. Men Submitted in partial fulnllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1997 O Copyright by Myrna Men Nationai LiBrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services sewices bibliographiques 395 WelJiiStreet 395. nie Wellington OtEawaON KIAW -ON K1AûN4 canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Iicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Biblioihèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, ioan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts Eom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. As with any thesis, there are many people to pay tribute to who helped me with this effort. It is with this in mind that 1 mention Dr. Herman Bakvis, whose assistance, advice and patience was of great value. Thanks also to Dr. Peter Aucoin and Dr. David Cameron for their commentary and suggestions. FinaLiy, 1 wish to thank my family and fnends who supported and encouraged me in my academic endeavours. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Decentering Ir:Excavating Stories of International

DECENTERING IR: EXCAVATING STORIES OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Zeynep Gulsah Capan urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201400709 Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grads einer Doktorin der Sozialwissenschaft (Dr. rer. pol.) der Universität Erfurt, Staatswissenschaftliche Fakultät 1 ABSTRACT: The thesis aims to underline the Eurocentrism of the field of international relations and the way in which the conceptualizations and writings of history contribute to the reproduction of specific narratives of international relations. The thesis argues that the ‘decentering’ of the field should not only focus on questioning the narratives produced in the center but also focus on the reproduction of Eurocentrism in the ‘periphery’. The thesis through the example of the ‘Cold War’ discusses the way in which the ‘Cold War’ has been written and the presuppositions about international relations that has been produced and reproduced in the center and in the periphery. KEYWORDS: Eurocentrism, Historiography, Cold War, Decentering, International Relations 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................3 I. DECENTERING INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS......................................4 II. SITUATING TURKEY.................................................................................7 III. ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY.........................................................10 SECTION I: HISTORIOGRAPHICAL OPERATIONS ON THE COLD WAR............12 SECTION II: STORIES OF SILENCES...........................................................................13 -

The Film-Work of Norman Mclaren in the Context of His Objectives

The Film-Work Norman McLaren Terence Dobson A thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury University of Canterbury 1994 Contents page Abstract iii List of Illustrations iv Preface v Introduction vii Part One Chapter One An Informative Drawing 1 Chapter Two The Early Years 23 Chapter Three McLaren at the G PO Film Unit 57 Part Two Chapter Four New York Interlude 103 Chapter Five Canada 128 Part Three Chapter Six Technical Processes 170 Chapter Seven Confluence and Conflict in Synchromy 197 Chapter Eight Venus and Mars 218 Conclusion 237 Chronology 248 Bibliography 249 Interviews, Films and Recordings 281 ill Abstract This thesis examines the film-work of Norman Mclaren in the context of his objectives. The thesis is divided into three parts, based on chronological divisions in McLaren's life. The first part deals with McLaren's formative years in Scotland and England and examines his early exposure to the social, artistic and institutional influences that were to shape his filmic output. The second part deals with Mclaren's maturation in the USA and Canada. His reaction to the contrasting working environment he found in each of the two countries is examined. In order to show McLaren's development more clearly, both parts one and two are based on a chronological sequencing. The third part of the thesis examines specific issues in relation to Mclaren and his work and as such is concerned principally with his mature output. McLaren's films contain incongruities, conflicts and apparent inconsistencies.