Versloot & Adamczyk 2017 Old Saxon Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If Sherds Could Tell Imported C

Everyday Products in the Middle Ages Ages Middle the in Products Everyday The medieval marketplace is a familiar setting in popular and academic Everyday Products accounts of the Middle Ages, but we actually know very little about the people involved in the transactions that took place there, and how their lives were influenced by those transactions. We know still less about the in the Middle Ages complex networks of individuals whose actions allowed raw materials to be extracted, hewn into objects, stored and ultimately shipped for market. Crafts, Consumption and the Individual With these elusive individuals in mind, this volume will explore the worlds of actors involved in the lives of objects. We are particularly concerned in Northern Europe c. AD 800–1600 with everyday products - objects of bone, leather, stone, ceramics, and base metal - their production and use in medieval northern Europe. The volume brings together 20 papers, first presented at the event ‘Actors and Affordable Crafts: Social and Economic Networks in Medieval northern Europe’, organised by the Universities of Bergen and York in February 2011. Through diverse case studies undertaken by specialists, and a combination of leading edge techniques and novel theoretical approaches, we aim to illuminate the identities and lives of the medieval period’s oft-overlooked actors. This collection then, does not engage directly with the traditional foci of research into medieval crafts - questions of economics, politics, or technological development - but rather takes a social approach. Neither are we concerned with the writing of a grand historical narrative, but rather with the painting of a number of detailed portraits, which together may prove far more illuminating than any generalising broadbrush approach and Irene Baug Ashby P. -

Karte Der Wahlkreise Für Die Wahl Zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag

Karte der Wahlkreise für die Wahl zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag gemäß Anlage zu § 2 Abs. 2 des Bundeswahlgesetzes, die zuletzt durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 03. Mai 2016 (BGBl. I S. 1062) geändert worden ist Nordfriesland Flensburg 1 Schleswig- Flensburg 2 5 4 Kiel 9 Rendsburg- Plön Rostock 15 Vorpommern- Eckernförde 6 Dithmarschen Rügen Ostholstein Grenze der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Länder Neu- 14 münster Grenze Kreise/Kreisfreie Städte 3 16 Segeberg Steinburg 8 Lübeck Nordwestmecklenburg Rostock Wahlkreisgrenze 11 17 Wahlkreisgrenze 29 Stormarn (auch Kreisgrenze) 7 Vorpommern- Cuxhaven Pinneberg Greifswald Schwerin Wittmund Herzogtum Wilhelms- Lauenburg 26 haven Bremer- 18-23 13 Stade Hamburg Mecklenburgische Saalekreis Kreisname haven 12 24 10 Seenplatte Aurich Halle (Saale) Kreisfreie Stadt Friesland 30 Emden Ludwigslust- Wesermarsch Rotenburg Parchim (Wümme) 36 Uckermark Harburg Lüneburg 72 Wahlkreisnummer Leer Ammerland Osterholz 57 27 Oldenburg (Oldenburg) Prignitz Bremen Gebietsstand der Verwaltungsgrenzen: 29.02.2016 55 35 37 54 Delmen- Lüchow- Ostprignitz- 28 horst 34 Ruppin Heidekreis Dannenberg Oldenburg Uelzen Oberhavel 25 Verden 56 58 Barnim 32 Cloppenburg 44 66 Märkisch- Diepholz Stendal Oderland Vechta 33 Celle Altmarkkreis Emsland Gifhorn Salzwedel Havelland 59 Nienburg 31 75-86 Osnabrück (Weser) Grafschaft 51 Berlin Bentheim 38 Region 43 45 Hannover Potsdam Brandenburg Frankfurt a.d.Havel 63 Wolfsburg (Oder) 134 61 41-42 Oder- Minden- 40 Spree Lübbecke Peine Braun- Börde Jerichower 60 Osnabrück Schaumburg -

The Stamps of the German Empire

UC-NRLF 6165 3fi Sfifi G3P6 COo GIFT OF Lewis Bealer THE STAMPS OF THE GERMAN STATES By Bertram W. H. Poole PART I "Stamps of the German Empire" BADEN MECKLENBURG-SCHWERIN BAVARIA MECKLENBURG-STREUTZ BERGEDORF OLDENBURG BREMEN PRUSSIA BRUNSWICK SAXONY HAMBURG SCHLESWIG-HOISTEIN HANOVER LUBECK WURTEMBERG HANDBOOK NUMBER 6 Price 35c PUBLISHED BY MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. BOSTON, MASS. i" THE STAMPS OF THE GERMAN EMPIRE BY BERTRAM W. H. POOLE AUTHOR OF The Stamps of the Cook Islands, Stamp Collector's Guide, Bermuda, Bulgaria, Hong Kong, Sierra Leone, Etc. MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. HANDBOOK No. 6 PUBLISHED BY MEKEEL-SEVERN-WYLIE CO. BOSTON, MASS. GIFT OF FOREWORD. In beginning this series of articles little is required in the way of an intro- ductory note for the title is lucid enough. I may, however, point out that these articles are written solely for the guidance of the general collector, in which category, of course, all our boy readers are included. While all im- portant philatelic facts will be recorded but little attention will be paid to minor varieties. Special stress will be laid on a study of the various designs and all necessary explanations will be given so that the lists of varieties appearing in the catalogues will be plain to the most inexperienced collector. In the "refer- ence list," which will conclude each f chapter, only > s.ucji s. arfif>s; Hifl >e in- cluded as may; ie,'con&tfJdrekt ;"e,ssntial" and, as such,' coming 'within 'the scope of on the.'phJlaJtetist'lcoUeetijig' ^ene^l" lines. .V. -

Accreditation of the City of Delmenhorst As “Safe Community” Within the Programme of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Community Safety Promotion

24. January 2011 Accreditation of the city of Delmenhorst as “Safe Community” within the programme of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Community Safety Promotion Impressum Accreditation of the city of Delmenhorst as “Safe Community” of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Community Safety Promotion Editor: The registered association Infantile Health (GiK e.V.), Delmenhorst City of Delmenhorst Editorial staff: Dr. Johann Böhmann, Dr. Birgit Warwas-Pulina, Andreas Kampe, Stella Buick Contact: Dr. Johann Böhmann, head physician of the paediatric clinic of Delmenhorst, Wildeshauser Str. 92, 27753 Delmenhorst Peter Betten, coordinator of the round table “Injury prevention”, city of Delmenhorst, Service 3 Delmenhorst, January 2011 II Preface Road traffic or household injuries, violence against women, children or dissidents cause damage to each individual and to the community, which cannot be accepted. Therefore prevention is very important in the community of Delmenhorst. The city of Delmenhorst has undertaken the task of avoiding injuries caused by accidents and violence by means of systematic precaution as far as possible. A successful prevention is the precondition for a cross-departmental and systematical approach. The prevention must not only include the reaction to the current occurrences, but must also include a comprehensive and systematic long-term, active strategy. With the report on hand “accreditation of the city of Delmenhorst as safe community” the community of Delmenhorst applies for the acceptance to the international network of the “Safe Communities”. The stakeholders in Delmenhorst would like to learn from the experiences of other countries and they want to provide the international community with their knowledge regarding prevention. Patrick de La Lanne Mayor of the city of Delmenhorst III Content 1 Introduction......................................................................................................... -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

Lessons from the Rise and Demise of the Self-Declared Caliphate of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq

IN A BROKEN DREAM: LESSONS FROM THE RISE AND DEMISE OF THE SELF-DECLARED CALIPHATE OF THE ISLAMIC STATE IN SYRIA AND IRAQ TAL MIMRAN* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................77 II. THE PRINCIPLE OF SOVEREIGNTY AND THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL ORDER.............................................79 III. THE CASE STUDYTHE ISLAMIC STATE BETWEEN 2014 AND 2017.......................................................................91 IV. THE DREAM OF THE CALIPHATE AND STATEHOOD................99 A. The Criteria for Statehood............................................100 1. Permanent Population............................................101 2. Defined Territory ....................................................102 3. Effective Government .............................................102 4. Capacity to Enter into Relations with Other States ............................................................103 B. What’s Recognition Got To Do with It? ........................103 V. FUNCTIONALISM, DETERRITORIALIZATION, AND THE ISLAMIC STATE IN THE AGE OF THE RISE OF NSAS............112 VI. CONCLUSION........................................................................127 I. INTRODUCTION The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Islamic State)1 is a terrorist organization that took over significant territories, in the context of the Syrian civil war,2 and declared itself a caliphate in June 2014.3 It transformed from a minor terrorist group into an alleged quasi-state, presenting capabilities and wealth like no * Doctorate -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

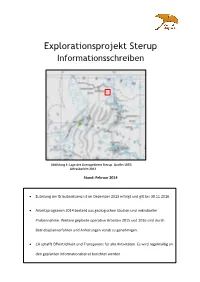

Explorationsprojekt Sterup Planung

Zusammenfassung Februar 2014 Explorationsprojekt Sterup Informationsschreiben Abbildung 1: Lage des Lizenzgebietes Sterup. Quelle: LBEG Jahresbericht 2012 Stand: Februar 2014 Zuteilung der Erlaubnislizenz ist im Dezember 2013 erfolgt und gilt bis 30.11.2016. Arbeitsprogramm 2014 besteht aus geologischen Studien und mikrobieller Probennahme. Weitere geplante operative Arbeiten 2015 und 2016 sind durch Betriebsplanverfahren und Anhörungen vorab zu genehmigen. CA schafft Öffentlichkeit und Transparenz für alle Aktivitäten. Es wird regelmäßig an den geplanten Informationsbeirat berichtet werden. Allgemeines Die Central Anglia AS, Oslo, plant ab 2014 im Kreis Schleswig-Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein, auf konventionelle Weise nach Öl und Gas zu suchen. Bisher waren die Gründer der Central Anglia für Großunternehmen schwerpunktmäßig im skandinavischen und deutschen Explorationsgeschäft tätig. Die über viele Jahre gewonnene Expertise ist die Grundlage für ein Engagement auch in Deutschland. Die vermutete Lagerstätte in der Lizenz Sterup liegt in Sandsteinschichten aus der Jura-und Triaszeit in 1.100-1.400 m Tiefe. Die Reservoireigenschaften sind aus Nachbarbohrungen bekannt und sind so gut, dass im Erfolgsfall rein konventionell gefördert werden kann und keinerlei Bezug zu der umstrittenen „Fracking-Technologie“ bestehen wird. Fracking ist kein Thema oder Geschäftsfeld für Cental Anglia. Sterup: Lage des Lizenzgebietes mit seismischen Linien, Lage des Salzstockes und geologischer Querschnitt durch die Lizenz Die bisher nur vermutete Lagerstätte ist nach Abschluss der laufenden geologischen Studien im Jahre 2015 durch seismische Vermessungen zu bestätigen. Das Einmessen von Seismiklinien stellt eine Verdichtung bereits vorhandener Linien dar, die in der 1 Explorationsprojekt Sterup - Informationsschreiben Vergangenheit gemessen wurden, wird aber nicht wie früher mit Sprengseismik sondern mit Vibratortechnik vermessen und dient der genaueren Definition der Gesteinslagerung im Untergrund. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Tourismus in Niedersachsen Und Speziell Im Reisegebiet Harz - Entwicklung Von 2000 Bis 2011

Dr. Wolfgang Vorwig (Tel. 0511 9898-2347) Tourismus in Niedersachsen und speziell im Reisegebiet Harz - Entwicklung von 2000 bis 2011 Niedersachsen bietet auf Grund seiner vielfältigen land- nach Deutschland, gegenüber dem Jahr 1999 entsprach dies schaftlichen Strukturen interessante Reise- und Urlaubszie- einem Zuwachs von 6,1 %. Mit 347,4 Mio. Übernachtungen le für seine Besucher. Diese reichen von Küsten- über wurden im Expojahr 5,5 % mehr gebucht als im Vorjahr. Die Heide- bis zu Mittelgebirgslandschaften. Weitreichende Ankünfte gingen bis zum Jahr 2003 wieder leicht bis auf knapp Angebote ermöglichen die unterschiedlichsten Urlaubsfor- 112,6 Mio. zurück um dann ab 2004 wieder über das Niveau men von z.B. Badeurlaub oder Rad-, Wander-, Wellness- des Jahres 2000 anzusteigen. Bei den Übernachtungen verlief und Reiturlaub. Auf Grund dieser breit gefächerten Mög- die Entwicklung ähnlich. Konnte dieses Niveau im Nachexpo- lichkeiten ist der Tourismus ein wichtiger Faktor für die jahr noch gehalten werden, wurde es in den Folgejahren wie- niedersächsische Wirtschaft. Im nachfolgenden Aufsatz der unterschritten. Seit 2006 hat die Zahl der Übernachtun- soll die Entwicklung des Tourismus in Niedersachsen sowie gen in Deutschland von einer Unterbrechung im Jahr 2009 im Reisegebiet Harz in den Jahren 2000 bis 2011 darge- (-0,2 % gg. dem Vorjahr) einmal abgesehen aber kontinuier- stellt werden. Der Harz soll hier näher betrachtet werden, lich zugenommen. So wurde 2011 mit 394 Mio. Übernach- da dieses Reisegebiet in der Vergangenheit wiederholt Ge- tungen ein neuer Höchstwert erreicht. genstand der Presseberichterstattung war. In den Grafi ken 1 und 2 sind die Entwicklungen der An- künfte und Übernachtungen in Deutschland im Vergleich Niedersachsen im Vergleich zur Bundesrepublik zu Niedersachsen als Messzahlen dargestellt. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

CUH Was Seemg More Tourist Traffic Than Usual. Harlingen Is a on The

The Frisians in 'Beowulf' Bremmer Jr., Rolf H.; Conde Silvestre J.C, Vázquez Gonzáles N. Citation Bremmer Jr., R. H. (2004). The Frisians in 'Beowulf'. In V. G. N. Conde Silvestre J.C (Ed.), Medieval English Literary and Cultural Studies (pp. 3-31). Murcia: SELIM. doi:•Lei fgw 1020 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/20833 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). THE FRISIANS IN BEOWULF- BEOWULF IN FRISIA: THE VICISSITUDES TIME ABSTRACT One of the remarkable aspects is that the scene of the main plot is set, not in but in Scandinavia. Equa!l)' remarkable is that the Frisian~ are the only West Germanic tribe to a considerable role in tvvo o{the epic's sub-plots: the Finnsburg Episode raid on Frisia. In this article, I willjirst discuss the significance of the Frisians in the North Sea area in early medieval times (trade), why they appear in Beowul{ (to add prestige), and what significance their presence may have on dating (the decline ajter 800) The of the article deals with the reception of the editio princeps of Beovvulf 1 881) in Frisia in ha!fofth!:' ninete?nth century. summer 1 1, winding between Iiarlingen and HU.<~CUH was seemg more tourist traffic than usual. Harlingen is a on the coast the province of Friesland/Fryslan, 1 \Vijnaldum an insignificant hamlet not far north from Harlingen. Surely, the tourists have enjoyed the sight of lush pastures leisurely grazed Friesian cattle whose fame dates back to Roman times.