Leps October 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergei Bulgakov and the Search for the Ecumenical Future

The Hour is Coming, and is Now Come: Sergei Bulgakov and the Search for the Ecumenical Future by Scott Allan Sharman A Thesis submitted to the Faculty the University of St. Michael’s College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College © Copyright by Scott Sharman 2014 The Hour is Coming, and is Now Come: Sergei Bulgakov and the Search for the Ecumenical Future Scott Sharman Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation draws upon the lived and written ecclesiology of Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov (1871-1944) in order to make theological and methodological contributions to the current debates surrounding the future of the Christian ecumenical movement. Part I lays the groundwork for the subsequent chapters. It begins with a brief introduction to Bulgakov’s personal history and context, as well as an identification of the most relevant primary and secondary sources on the topics of Church and ecumenism. This is followed by a short survey of the origins and significant highlights of the ecumenical movement in the twentieth century, and an identification of certain challenges which have emerged in the latter part of the century. Part II represents the heart of the study. It sets out to engage in an in-depth examination of the key features of Bulgakov’s ecumenical thought and career. Initial attention is given to both the personal and intellectual influences which shaped Bulgakov’s vision of Christian unity. -

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD 1 Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops Of

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York issued a letter on 16th February outlining their proposals for continuing to address, as a church, questions concerning human sexuality. The Archbishops committed themselves and the House of Bishops to two new strands of work: the creation of a Pastoral Advisory Group and the development of a substantial Teaching Document on the subject. This paper outlines progress toward the realisation of these two goals. Introduction 1. Members of the General Synod will come back to the subject of human sexuality with very clear memories of the debate and vote on the paper from the House of Bishops (GS 2055) at the February 2017 group of sessions. 2. Responses to GS 2055 before and during the Synod debate in February underlined the point that the ‘subject’ of human sexuality can never simply be an ‘object’ of consideration for us, because it is about us, all of us, as persons whose being is in relationship. Yes, there are critical theological issues here that need to be addressed with intellectual rigour and a passion for God’s truth, with a recognition that in addressing them we will touch on deeply held beliefs that it can be painful to call into question. It must also be kept constantly in mind, however, that whatever we say here relates directly to fellow human beings, to their experiences and their sense of identity, to their lives and to the loves that shape and sustain them. -

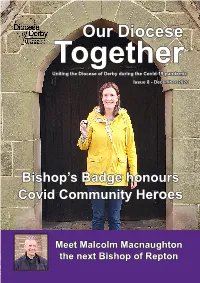

Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby During the Covid-19 Pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020

Our Diocese Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby during the Covid-19 pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020 Bishop’s Badge honours Covid Community Heroes Meet Malcolm Macnaughton the next Bishop of Repton News Advent Hope Between 30 November and 24 December 2020, Bishop Libby invites you to join her each week for an hour of prayer and reflection based upon seasonal Bible passages and collects as together we look for the coming of Christ and the hope that gives us of his kingdom. Advent Hope is open to all and will be held on Mondays from 8am - 9am and repeated on Thursdays from 8pm - 9pm. Email [email protected] for the access link. Interim Diocesan Director of Education announced Canon Linda Wainscot, formerly Director of Education for the Diocese of Coventry, will take up the position as Interim Diocesan Director of Education for two days a week during the spring term 2021. Also, Dr Alison Brown will continue to support headteachers and schools, offering one and two days a week as required, ensuring their Christian Distinctiveness within the diocese. Both roles will be on a consultancy basis, starting in January 2021. Linda said: “Having had a long career in education, I retired in August 2020 from my most recent role as Diocesan Director of Education (DDE) for the Diocese of Coventry (a post I held for almost 20 years). Prior to this, I was a teacher and senior leader in maintained and independent schools and an FE College as well as being involved in teacher training. In addition to worshipping in Rugby, I am privileged to be an Honorary Canon of Coventry Cathedral and for two years I was the chair of the Anglican Association of Directors of Education. -

The Louth Herald

The Louth Herald The magazine of the Team Parish of Louth 60p JUNE 2014 A celebratery walk of about 2 miles, from Westminster Abbey where we had gathered, to St. Paul's Cathedral, led by a band, on a warm, sunny afternoon began this momentous day of thankgiving and happiness. On reaching the Ca- thedral, all the "1994 Ordinands", retired to the Crypt to robe in albs and white stoles. We then met the Archbishop, Justin Welby, for photographs. As we stood on the steps we were a wall of white. The Archbishop greeted us and chat- ted informally.Photographs over, we were ushered through the three entrences into the Cathedral. I was aware of a kind of roaring noise and unrealistically thought it was a lawn mower, then as it increased, I thought it was an areoplane. On stepping inside the relative darkness after the bright sunshine , I was momentarily blinded but the noise had now reached a crescendo. As I regained my sight, I realized the whole enormous congregation was standing and applauding us. Tears sprang into my eyes. It was overwhelming and the first time that it dawned on me that we were re- garded as pioneers. It was a strangely lonely and emotional walk up the aisle to my seat. I am told the applause lasted about 25 minutes. Twenty years ago at my ordination in Lincoln Cathedral, I had thought that then was the pinacle of our struggle to be accepted on equal terms, but Saturday, 3rd. of May, at St. Paul's was a final aknowledgement. -

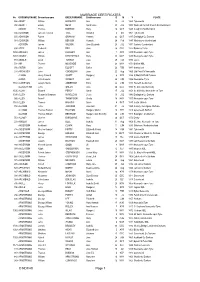

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

To Love and Serve the Lord

TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) Published by the Lutheran World Federation 150, route de Ferney P.O. Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland © Copyright 2012, jointly by The Lutheran World Federation and the Secretary General of the Anglican Communion. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permis- sion in writing from the copyright holders, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Printed in France by GPS Publishing TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) To Love and Serve the Lord Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) Editorial assistance: Cover: LWF/DTPW staff LWF/OCS staff Anglican Communion Office staff Photo: ACNS/ Neil Vigers Design and Layout: Photo research and design: LWF/OCS staff LWF/DTPW staff Anglican Communion Office staff ISBN 978-2-940459-24-7 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 4 I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 6 II. Diakonia -

The Dorcan Church

Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church 5-06-2013 v2 1 http://www.dorcanchurch.co.uk/ Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ Our Mission Statement God calls us as a Church to live and share the Good News of God’s Love so that all people have the opportunity to become followers of Jesus Christ. Relying on the Holy Spirit’s Power, we commit ourselves to being open to change to make mission our top priority by: Building bridges within our local communities Offering worship that is welcoming, understandable and centered in the presence of God Building relationships where all are cared for and can grow in wholeness Making opportunities to pray regularly and together Helping people understand the Christian faith and live it Actively supporting the values of God’s kingdom: justice, reconciliation and care for people in need Who we are and what we are doing The Dorcan Church is a local Ecumenical Partnership between the Church of England and the Methodist Church serving the Swindon urban villages of Covingham, Nythe, Liden and Eldene. The partnership includes the congregation of St Paul’s Church Centre, Covingham, St Timothy’s Church, Liden and Eldene Community Centre. We are a mix of friendly, lively, all age people, that present as a ‘bag of surprises’, but needing more 20s and 30s. We need you to join with our Methodist Minister and Ministry Team to help us grow in number and engage with our local community in new ways. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

In January 1991 Gordon Sleight Was Still the Vicar of Crosby with Joanna Anderson As Curate

In January 1991 Gordon Sleight was still the Vicar of Crosby with Joanna Anderson as Curate. The Youth & Community Worker was Mick Maskell with Pat Newcombe as his assistant. The Parish Clerk was Janice Brader and the Church Wardens were Barbara Scott and Norman Jackson. Tim Savage was PCC Secretary and Steve Barker was PCC Treasurer. Lesley Sleight, the Parish Magazine Editor, recorded that 1991 would see some changes in the magazine as a new team would be taking over during the next few months. Subscriptions remained the same at 15p. The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity was marked with a series of services in the Town Centre Parishes between 18-25 January. The Speaker for the Lent United Services and discussions, scheduled for February and March, would be the Right Reverend David Tustin, the Bishop of Grimsby. Pat Newcombe wrote that the St George’s Credit Union, which was set up during the summer of 1989 with 30 members, now had funds of £2,000, and it should become registered this year. To join this Credit Union a member had to live within the Parish of Crosby or be connected with the work of the Church or Community Department. All members had a say in how the Credit Union operates. A Credit Union was useful for many reasons; it kept local money in the local area. Loans were made from the savings pool and repayments allowed this money to be re-loaned and so on. No one was exploited and interest rates are set by law and are the same for all members. -

Services & Music

S ERVICES & M USIC August 2017 ~ July 2018 Sunday 30 July Choir in Residence Today Seventh Sunday after Trinity St Peter’s, Earley 7.40am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 8.00am Holy Communion (BCP) QUIRE 10.00am CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE Preacher Canon Professor Martin Gainsborough Setting Darke in F Psalm 105.1-11 Motet O king all glorious, Willan Hymns Processional 440 Lobe den Herren [omit v.5] Offertory 238 Melcombe Communion 276 Bread of heaven Post-communion 391 Gwalchmai Voluntary Voluntary in D – Croft 3.30pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Preacher The Dean Responses Ayleward Psalm 75 Canticles Wood in E flat (No.1) Anthem Save us, O Lord – Bairstow Hymns 431 Hereford; 239 Slane Voluntary Prelude in a – Krebs Monday 31 July Choir in Residence Today Ignatius of Loyola, Founder of the Society of Jesus, 1556 St Mark’s Episcopal Church Berkeley, CA, USA 8.30am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 12.30pm Eucharist ELDER LADY CHAPEL 5.15pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Responses Bounemani Psalm 146 Canticles Friedell in F Hymn 456 Sandys Anthem Lass dich nur nichts nicht dauren – Brahms Tuesday 1 August Choir in Residence Today Feria St Mark’s Episcopal Church, Berkeley, CA, USA 8.30am Morning Prayer BERKELEY CHAPEL 12.30pm Eucharist SEAFARERS’ CHAPEL 1.15pm LUNCHTIME RECITAL NAVE Untune the Sky – Oxford-based Vocal Consort 5.15pm CHORAL EVENSONG QUIRE Responses Bounemani Psalm 6 Canticles All Saints Evening Service – Hirten Hymn 485 Thornbury Anthem Perfect love casteth out fear – Southwood 2 bristol-cathedral.co.uk Wednesday 2 August Choir in Residence Today -

Cycle of Prayer Those I Live With, Those I Rub Shoulders With, Those I Work With, Those I Don’T Get on With, Thursday 29 May Each Be the Focus of My Prayer

September 2016 Wednesday 28 Friday 30 Pray for all preparing for the new term at This world I live in, this town I live in, University, especially those leaving home for this street I live in, this house I live in, the first time may each be the focus of my prayer. Cycle of Prayer Those I live with, those I rub shoulders with, those I work with, those I don’t get on with, Thursday 29 may each be the focus of my prayer. Michael and All Angels Those who laugh, those who cry, those who Thursday 1 Monday 5 hurt, those who hide, Pray that the Church as a body will be em- In the United Benefice of Morton and Stone- For a first day at school powered to stand up against powers of dark- may each be the focus of my prayer. broom with Shirland the parish of Holy Cross, Prayers centred less on self and more on ness and bring God’s light into the world. Morton, during the vacancy of Vicar, do pray O God, the strength of my life, let me be others, for those who have responsibility for the care less on my circumstances, more on the needs strong today as I meet new people in new If we had a fraction of the faith in you that you of this parish and those who will support the places. have in us of others. Churchwardens and PCC Clergy: May my life be likewise centred less on self help me to discover friends among strangers, then this world would be transformed, Lord. -

Growing Together in Unity and Mission: an Agreed Statement by the International Anglican – Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission

Commentary and study guide on Growing Together in Unity and Mission: An Agreed Statement by the International Anglican – Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission PART ONE: The achievements of Anglican – Roman Catholic Theological Dialogue A. INTRODUCTION (paragraphs 1 to 10) It is often said that the ecumenical movement has come to a stop and is failing to make any progress. After the exciting days of the 1960s when old prejudices appeared to die and Christians started to talk to each other and pray together it has been hard to see any concrete signs of progress being made. As a result there has been a loss of interest in ecumenism. In many cases attention has shifted from attempting to find schemes for organic union at the institutional level to pursuing local initiatives to bring Christians together in prayer, witness and service at the parish level. In the Church of England the multiplication of Local Ecumenical Projects can be seen as an expression of this. But although it has become common to speak of an ‘ecumenical winter’ we often forget just how much progress has been made in the past forty years and overlook the way in which a growing together of the churches has fostered and encouraged local initiatives. Towards the end of his life, Oliver Tomkins, a former Bishop of Bristol, wrote that ‘All this talk about the ‘winter of ecumenism’ makes me look again at the snow drops in my garden. Perhaps God’s timescale was longer than we reckoned’. An Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) was set up in 1966 and produced reports on the Eucharist, the ministry and authority, claiming that it had reached ‘substantial agreement’ in the first two of these reports.