Mission and Ministry’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

April 2019 Your Bi-Monthly Newsletter

Deanery News April 2019 Your Bi-monthly Newsletter Dear all It is good to hear how people are keeping Lent and preparing for our Easter and Pentecost celebrations in a variety of ways. Do please have a look through the newsletter at the things that have happened and that are going on. We always welcome news and updates, so please keep sending them to Debbie at [email protected] who you can also email to subscribe to this newsletter if you don’t already (or unsubscribe if you want to). Our new Bishop of Derby, Rt Rev Libby Lane, is also preparing to fully take up her post. She will be installed at Derby Cathedral on Saturday 25th at 2.30pm. Everyone is very welcome to attend. Bishop Libby is then planning to visit each of the Deaneries, to meet a wide range of people and to pray with them. She will be visiting Mercia Deanery on Wednesday 5th June, as part of which she will be speaking at our Deanery Thy Kingdom Come service, which will be hosted by St Mark’s Winshill starting at 7:45pm. Again, everyone is very welcome. At our recent Deanery Synod meeting, we thought about the Church of England’s programme of change, Setting God’s People Free. This is designed to “enable the whole people of God to live out the Good News of Jesus confidently in all of life, Sunday to Saturday.” There is more information and some practical tips at https:// www.churchofengland.org/SGPF In the light of this, we examined our Deanery priorities, which we agreed should be: 1. -

THY KINGDOM COME Codes of Conduct

TEAM WORK: PHOTOS: REVD HUW RIDEN HUW REVD PHOTOS: HOW SPORT GOOD NEWS FROM THE DIOCESE OF EXETER | JULY 2019 RUNNING JOHN BELL AT THE RACE HELPS US HOLY GROUND The Right Revd Nick LIVE OUT Iona musician to be special McKinnel reflects on guest at Cathedral service... the number of sport and he has planned the analogies in the New THE GOSPEL music for the Eucharist Testament The Right Revd Members of the re-established Nick McKinnel Exeter Diocesan Cricket Team Bishop of Plymouth That’s true not only for the obvious team sports. t is promising to be a great summer of sport: These days every professional golfer or cyclist has Wimbledon this month, an Ashes series in August, a team behind them. the Rugby World Cup in September hopefully As we know from church life, we are ‘better with a sprinkling of Chiefs’ players in the squad, together’, called into the body of Christ, to work for the prospect of Plymouth Argyle and Exeter City Diocese joins the whole world to feel power of prayer the cause of God’s kingdom. Ibattling out in League Two later in the year. Even the Sport requires order, rules and parameters Diocesan cricket team revived its fortunes in a modest within which a game can be played. These might way! be white lines on a tennis court or long hallowed The glory of sport, whether we watch or play, is THY KINGDOM COME codes of conduct. pitting skill against skill, strength against strength. It is not acceptable that anything goes, that It tests character, brings glory, makes heroes and everyone’s view point is equally valid or that rules rayer has been centre offers hope – think of the English teams trailing can be made up as we go along. -

Bishop John Taylor RIP 1929-2016

July/August 2016 Issue 06 News The Diocese of St Albans in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Luton & Barnet Bishop John Taylor RIP 1929-2016 Bishop John Taylor was In 1993 I wrote a guide to Bishop of St Albans from 1980 Church communications and to 1995, preceeding Bishop Bishop John contributed Christopher Herbert. the foreword.” It said: “The His appointment was a return Church’s communication to the county of his childhood, should be accessible, not having attended Watford Boys obscure, and human, not lost Grammar School and having in technicality. In these media- found faith at the youth group minded days, the Church in St Luke’s Church, Watford. needs to follow the example of Ordained in 1956, his early its Lord in taking infinite pains parish experienced was to get the message heard.” followed by a long and Peter reflects: “Bishop John’s distinguished teaching career advice is as relevant today as it at Oak Hill. Following that was more than 20 years ago.” he had 8 very happy years Bishop Alan took Bishop in Chelmsford Diocese as John’s funeral service in a DDO, some of that time packed cathedral. The notes being combined with parish to the service say: “In spite ministry in Woodford Wells. of his apprehensions, John There followed by 5 years was Bishop of St Albans for as Archdeacon of West Ham 15 deeply happy years, and before his consecration. loved ministering to the clergy He was troubled at the thought of leaving parish life and people of the St Albans diocese, with Linda always for Archdiaconal responsibilities, but was obedient to by his side. -

A Report on the Developments in Women's Ministry in 2018

A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry in 2018 WATCH Women and the Church A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry 2018 In 2019 it will be: • 50 years since women were first licensed as Lay Readers • 25 years since women in the Church of England were first ordained priests • 5 years since legislation was passed to enable women to be appointed bishops In 2018 • The Rt Rev Sarah Mullaly was translated from the See of Crediton to become Bishop of London (May 12) and the Very Rev Viv Faull was consecrated on July 3rd, and installed as Bishop of Bristol on Oct 20th. Now 4 diocesan bishops (out of a total of 44) are women. In December 2018 it was announced that Rt Rev Libby Lane has been appointed the (diocesan) Bishop of Derby. • Women were appointed to four more suffragan sees during 2018, so at the end of 2018 12 suffragan sees were filled by women (from a total of 69 sees). • The appointment of two more women to suffragan sees in 2019 has been announced. Ordained ministry is not the only way that anyone, male or female, serves the church. Most of those who offer ministries of many kinds are not counted in any way. However, WATCH considers that it is valuable to get an overview of those who have particular responsibilities in diocese and the national church, and this year we would like to draw attention to The Church Commissioners. This group is rarely noticed publicly, but the skills and decisions of its members are vital to the funding of nearly all that the Church of England is able to do. -

Bishop Gets All Steamed up to Celebrate Christmas

E I D S The year’s The films that IN news in sparked a Hunger review in 2012 4,5 p11 THE SUNDAY, JANUARY 6, 2013 No: 6158 www.churchnewspaper.com PRICE £1.35 1,70j US$2.20 CHURCH OF ENGLAND THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER ESTABLISHED IN 1828 NEWSPAPER Group to tackle Synod impasse By Amaris Cole in the Synod and across the coming months we will find the February and again in May to lation is ready for introduction to Church. means to make that a reality”. come to a decision on the new the Synod there will be a separate THE WORKING group on the “That is why we will begin the The Bishop of Coventry added package of proposals which it decision about the membership of new legislative proposals on process with conversations at var- that he was also happy to have intends to bring to the Synod in the Steering Committee. women bishops was announced ious levels outside the legislative been asked to be a member of the July. This new Steering Committee, just before Christmas, containing process. newly announced group, working The brief includes facilitating which will, as usual, contain only only two members who voted “Many people on different sides towards the mandate given by the discussions with a wide range of those who support the legislation, against the previous legislation in of the debate have stated that they Archbishops’ Council. people across the Church in Feb- will have the responsibility for the November. want to find a way forward – my The working group’s task is to ruary. -

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD 1 Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops Of

GS Misc 1158 GENERAL SYNOD Next Steps on Human Sexuality Following the February 2017 Group of Sessions, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York issued a letter on 16th February outlining their proposals for continuing to address, as a church, questions concerning human sexuality. The Archbishops committed themselves and the House of Bishops to two new strands of work: the creation of a Pastoral Advisory Group and the development of a substantial Teaching Document on the subject. This paper outlines progress toward the realisation of these two goals. Introduction 1. Members of the General Synod will come back to the subject of human sexuality with very clear memories of the debate and vote on the paper from the House of Bishops (GS 2055) at the February 2017 group of sessions. 2. Responses to GS 2055 before and during the Synod debate in February underlined the point that the ‘subject’ of human sexuality can never simply be an ‘object’ of consideration for us, because it is about us, all of us, as persons whose being is in relationship. Yes, there are critical theological issues here that need to be addressed with intellectual rigour and a passion for God’s truth, with a recognition that in addressing them we will touch on deeply held beliefs that it can be painful to call into question. It must also be kept constantly in mind, however, that whatever we say here relates directly to fellow human beings, to their experiences and their sense of identity, to their lives and to the loves that shape and sustain them. -

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

For PSYCHICAL STUDIES

The CHURCHES’ for PSYCHICAL and SPIRITUAL STUDIES QUARTERLY REVIEW V No. 57 ■ September 1968 Contents include: W? Transplant Surgery .. 12-13 Rev. Dr. K. G. Cuming, Major Tudor Pole, Mr. Cyril Smith C.F.P.S.S. Recommendations to Lambeth Conference .. 9 Book Reviews .. 14-16 Readers’ Forum 17-18 C.F.P.S.S. Pilgrimages .. 3 Healing News .. 6 ONE SHILLING & SIXPENCE (U.S.A, and CANADA—25 Cents) The Churches’ Fellowship for Psychical and Spiritual Studies Headquarters: 5/6 Denison House, Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, S.W.l (01-834 4329) Founder—Lt.-Col. Reginald M. Lester, F.J.I. President—The Worshipful Chancellor The Rev. E. Garth Moore, M.A., J.P. Vice-President—The Bishop of Southwark Chairman—Lt.-Col. Reginald M. Lester, F.J.I. Vice-Chairman—The Rev. Canon J. D. Pearce-Higgins, M.A.. Hon. C.F. General and Organizing Secretary—Percy E. Corbett, Esq. Hon. General Secretary—Rev. Dr. K. G. Cuming, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Hon. Secretary Youth Section—Miss O. Robertson Patrons: Bishop of London Bishop of Southwell Rev. Dr. Leslie Weatherhead Bishop of Birmingham Bishop of Wakefield Canon The Ven. A. P. Shepherd Bishop of Bristol Bishop of Worcester Rev. Lord Soper Bishop of Carlisle Bishop of Pittsburgh, U.S.A. Rev. Dr. Leslie Newman Bishop of Chester Rt. Rev. Dr. G. A. Chase E. J. Allsop, J.P. Bishop of Chichester Very Rev. Dr. W. R. Matthews George H. R. Rogers, C.B.E., M.P. Bishop of Colchester Ven. E. F. Carpenter Dr. -

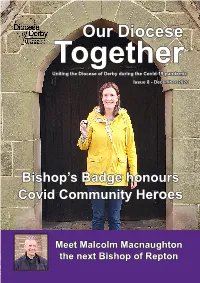

Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby During the Covid-19 Pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020

Our Diocese Together Uniting the Diocese of Derby during the Covid-19 pandemic Issue 8 - December 2020 Bishop’s Badge honours Covid Community Heroes Meet Malcolm Macnaughton the next Bishop of Repton News Advent Hope Between 30 November and 24 December 2020, Bishop Libby invites you to join her each week for an hour of prayer and reflection based upon seasonal Bible passages and collects as together we look for the coming of Christ and the hope that gives us of his kingdom. Advent Hope is open to all and will be held on Mondays from 8am - 9am and repeated on Thursdays from 8pm - 9pm. Email [email protected] for the access link. Interim Diocesan Director of Education announced Canon Linda Wainscot, formerly Director of Education for the Diocese of Coventry, will take up the position as Interim Diocesan Director of Education for two days a week during the spring term 2021. Also, Dr Alison Brown will continue to support headteachers and schools, offering one and two days a week as required, ensuring their Christian Distinctiveness within the diocese. Both roles will be on a consultancy basis, starting in January 2021. Linda said: “Having had a long career in education, I retired in August 2020 from my most recent role as Diocesan Director of Education (DDE) for the Diocese of Coventry (a post I held for almost 20 years). Prior to this, I was a teacher and senior leader in maintained and independent schools and an FE College as well as being involved in teacher training. In addition to worshipping in Rugby, I am privileged to be an Honorary Canon of Coventry Cathedral and for two years I was the chair of the Anglican Association of Directors of Education. -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

1907 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America 1907 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF THE GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE -roe~tant epizopal eburib IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Held in the City of Richmond From October Second to October Nineteenth, inclusive In the Year of Our Lord 1907 WITH APPENDIcES PRINTED FOR THE CONVENTION 1907 SECRETABY OF THE HOUSE OF DEPUTIES. THE REV. HENRY ANSTICE, D.D. Office, 281 FOURTH AVE., NEW YORK. aTo whom, as Secretary of the Convention, all communications relating to the general work of the Convention should be addressed; and to whom should be forwarded copies of the Journals of Diocesan Conventions or Convocations, together with Episcopal Charges, State- ments, Pastoral Letters, and other papers which may throw light upon the state of the Church in the Diocese or Missionary District, as re- quired by Canon 47, Section II.