Deconstructing Conventual Franciscan Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUEBLA* Municipios Entidad Tipo De Ente Público Nombre Del Ente Público

Inventario de Entes Públicos PUEBLA* Municipios Entidad Tipo de Ente Público Nombre del Ente Público Puebla Municipio 21-001 Acajete Puebla Municipio 21-002 Acateno Puebla Municipio 21-003 Acatlán Puebla Municipio 21-004 Acatzingo Puebla Municipio 21-005 Acteopan Puebla Municipio 21-006 Ahuacatlán Puebla Municipio 21-007 Ahuatlán Puebla Municipio 21-008 Ahuazotepec Puebla Municipio 21-009 Ahuehuetitla Puebla Municipio 21-010 Ajalpan Puebla Municipio 21-011 Albino Zertuche Puebla Municipio 21-012 Aljojuca Puebla Municipio 21-013 Altepexi * Inventario elaborado con información del CACEF y EFSL. 19 de marzo de 2020 Inventario de Entes Públicos PueblaPUEBLA* Municipio 21-014 Amixtlán Puebla Municipio 21-015 Amozoc Puebla Municipio 21-016 Aquixtla Puebla Municipio 21-017 Atempan Puebla Municipio 21-018 Atexcal Puebla Municipio 21-019 Atlixco Puebla Municipio 21-020 Atoyatempan Puebla Municipio 21-021 Atzala Puebla Municipio 21-022 Atzitzihuacán Puebla Municipio 21-023 Atzitzintla Puebla Municipio 21-024 Axutla Puebla Municipio 21-025 Ayotoxco de Guerrero Puebla Municipio 21-026 Calpan Puebla Municipio 21-027 Caltepec Puebla Municipio 21-028 Camocuautla Puebla Municipio 21-029 Caxhuacan Inventario de Entes Públicos PueblaPUEBLA* Municipio 21-030 Coatepec Puebla Municipio 21-031 Coatzingo Puebla Municipio 21-032 Cohetzala Puebla Municipio 21-033 Cohuecan Puebla Municipio 21-034 Coronango Puebla Municipio 21-035 Coxcatlán Puebla Municipio 21-036 Coyomeapan Puebla Municipio 21-037 Coyotepec Puebla Municipio 21-038 Cuapiaxtla de Madero Puebla Municipio -

Distrito Judicial De Puebla, Puebla. Número De Notaría Titular: Domicilio: Telefóno: Pública: 1 Sandra Giovanna Rivero Pastor

Distrito Judicial de Puebla, Puebla. Número de Notaría Titular: Domicilio: Telefóno: Pública: 1 Sandra Giovanna Rivero Pastor. AV. 25 PONIENTE No.111. Colonia "El Carmen". (222) 243-95-61, 243-32-99, 243-05-55. AV. 11 SUR 7114, TERCER PISO. COLONIA "SAN JOSÉ 2 Juan Tejeda Foncerrada. MAYORAZGO" (222)2-19-09-63 DOMICILIO: AV. 17 PONIENTE No. 1122. COLONIA: 3 Nicolás Vázquez Alonso. SANTIAGO. (222)243-67-00, 2-40-33-33, 2-40-33-66 CIRCUITO JUAN PABLO II No. 3117 COLONIA. LAS 4 Norma Romero Cortés. (222)230-33-33, 230-17-30, 230-36-30, 249-94-99 230-44-30 ÁNIMAS 5 Antonio Tinoco Landa. AV. 15 PONIENTE No. 905. COLONIA: SANTIAGO. (222)240-62-29, 240-64-14, 240-64-06 6 Pablo Daniel González Aragón Sánchez. AVENIDA TEZIUTLÁN SUR No. 67 1/2. COLONIA: LA PAZ. (222), 296-60-14, 232-51-94, 226-73-00 PRIVADA 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE No. 1502. COLONIA: EL 7 Juan Crisóstomo Salazar y Orea. CARMEN (222)237-97-15. 8 José Neyif Irabien Medina. CALLE 12 NORTE No.606. COLONIA: CENTRO. (222)246-53-27, 246-59-15. 9 Fernando de Unanue Sentmanat. AV. 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE No.2710. COLONIA: EL CARMEN. (222)243-09-41, 243-84-87 10 María Victoria Bustos Soto. AV. 23 ORIENTE No. 3. COLONIA: EL CARMEN. (222)243-56-65, 243-59-00. 11 Raúl Reyna Asomoza. PRIVADA 25 PONIENTE No.120. COLONIA: EL CARMEN. (222) 243-06-61. 12 Cesar Martínez Solano. AV. JUÁREZ No.3510. COLONIA: LA PAZ. -

RESOLUCION Núm. RES/133/99 RESOLUCION POR LA QUE SE

RESOLUCION Núm. RES/133/99 RESOLUCION POR LA QUE SE DETERMINA LA ZONA GEOGRAFICA DE PUEBLA-TLAXCALA PARA FINES DE DISTRIBUCION DE GAS NATURAL R E S U L T A N D O Primero.- Que el Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la Ley Reglamentaria del Artículo 27 Constitucional en el Ramo del Petróleo, publicado en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 11 de mayo de 1995, permite la participación de los sectores social y privado en la actividad de distribución de gas natural, sujeta dicha actividad a un régimen de permisos; Segundo.- Que de acuerdo con lo dispuesto por el artículo 26 del Reglamento de Gas Natural (en lo sucesivo el Reglamento), todo permiso de distribución debe otorgarse para una zona geográfica; Tercero.- Que en los términos del artículo 26 antes invocado, las zonas geográficas para fines de distribución deben ser determinadas por la Comisión Reguladora de Energía (en lo sucesivo la Comisión), considerar los elementos que permitan el desarrollo rentable y eficiente del sistema de distribución correspondiente y oír a las autoridades federales y locales involucradas; Cuarto.- Que la Comisión expidió la Directiva sobre la Determinación de Zonas Geográficas para Fines de Distribución de Gas Natural DIR/GAS/003/96, publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 27 de septiembre de 1996 (en lo sucesivo la Directiva de Zonas Geográficas), la cual establece los criterios y lineamientos que debe utilizar esta Comisión al determinar zonas geográficas para fines de distribución, y Quinto.- Que con fecha 12 de julio de 1999 Gaz de France, S.A., presentó a esta Comisión la manifestación de interés en los términos del Artículo 39 del Reglamento y del capítulo 5 de la Directiva de Zonas Geográficas para desarrollar un sistema de distribución de gas natural en los municipios de Amozoc, Coronango, Cuautlancingo, Huejotzingo, Juan C. -

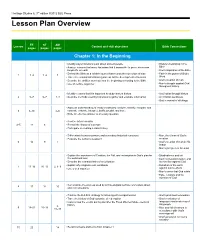

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Evangelization and Cultural Conflict in Colonial Mexico

Evangelization and Cultural Conflict in Colonial Mexico Evangelization and Cultural Conflict in Colonial Mexico Edited by Robert H. Jackson Evangelization and Cultural Conflict in Colonial Mexico Edited by Robert H. Jackson This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Robert H. Jackson and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5696-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5696-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Maps and Figures .......................................................................... vii Maps ......................................................................................................... xii Introduction ............................................................................................ xvii Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Miracle of the Virgin of the Rosary Mural at Tetela del Volcán (Morelos): Conversion, the Baptismal Controversy, a Dominican Critique of the Franciscans, and the Culture Wars in Sixteenth Century Central Mexico Robert H. Jackson Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Barbara and Dennis Tedlock

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org BARBARA AND DENNIS TEDLOCK Interviewed February 11-12 2005 in the weaving workshop of Angel Xiloj, Momostenango, Guatemala BARBARA TEDLOCK is an anthropologist and ethnographer whose work has focused on the Zuni of the American Southwest and the Maya of Highland Guatemala. She is the author of The Beautiful and the Dangerous: Encounters with the Zuni Indians, Time and the Highland Maya, and The Woman in the Shaman’s Body. DENNIS TEDLOCK has devoted his career as a poet, translator and anthropologist to the understanding and dissemination of native American literature. He is the author of the Finding the Center: the Art of the Zuni Storyteller, Breath on the Mirror: Mythic Voices and Visions of the Living Maya and numerous other books, and is translator and editor of Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life. The Tedlocks teach at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where Barbara is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and Dennis is the McNulty Professor of English and Research Professor of Anthropology. In this interview, the Tedlocks discuss: The creation and preservation of texts in the Maya region after the Spanish Conquest The Popol Vuh The Rabinal Achi dance drama The 260 day Tzolkin calendar The role of the daykeeper in a Highland Maya community The religious and political structure of the town of Momostenango The ceremonial day Wajxaqib Batz The importance of books for the modern Maya The role -

Municipio De San Pedro Cholula, Puebla Tesoreria Municipal Lineamientos De Información Pública Financiera Para El Fondo De Aportaciones Para La Infraestructura Social

MUNICIPIO DE SAN PEDRO CHOLULA, PUEBLA TESORERIA MUNICIPAL LINEAMIENTOS DE INFORMACIÓN PÚBLICA FINANCIERA PARA EL FONDO DE APORTACIONES PARA LA INFRAESTRUCTURA SOCIAL. PERIODO DEL 01 DE ABRIL AL 30 DE SEPTIEMBRE 2018 Monto recibido FAIS (FISM) $14,016,276.30 Ubicación Obra o acción a realizar Costo Meta Beneficiarios Entidad Municipio Localidad 18022 CONSTRUCCION DE SAN CRISTOBAL BARDA PERIMETRAL EN EL SAN PEDRO 39,926.78 PUEBLA TEPONTLA Y SANTA 312.33 M-L 210 PERSONAS BACHILLER DIEGO RIVERA CHOLULA MARIA ACUEXCOMAC CLAVE 21EBH09430 18061 MEJORAMIENTO DE COMEDOR ESCOLAR EN LA SAN PEDRO SAN FRANCISCO 23,132.91 PUEBLA 1 MODULO 220 ALUMNOS ESCUELA PRIMARIA BENITO CHOLULA CUAPA JUAREZ CLAVE 21DPRO338T SANTA MA. 18063 AMPLIACION DE ACUEXCOMAC, SAN INFRAESTRUCTURA FRANCISCO CUAPA, SANITARIA EN LA PRIV. SAN PEDRO SAN DIEGO PORFIRIO DIAZ; PRIVADA 88,814.11 PUEBLA 1084.06 M-L 688 PERSONAS CHOLULA CUACHAYOTLA, SAN HUAQUECHULA, CALLE CRISTOBAL VENADITO; PRIVADA IGNACIO TEPONTLA, SAN ALLENDE; PRIVADA CAÑADA MATIAS COCOYOTLA 18069 AMPLIACION DE SAN PEDRO SANTA BARBARA DRENAJE PLUVIAL EN LA C. 686,258.72 120 M-L 900 PERSONAS CHOLULA ALMOLOYA SEGUNDA DE REVOLUCION PUEBLA ACUEXCOMAC, TEPALCATEC, SAN 18094CONSTRUCCION DE DIEGO CUARTO PARA BAÑO TIPO DE SAN PEDRO CUACHAYOTLA, 1,052,009.54 PUEBLA 14 MODULOS 56 PERSONAS UNA SECCION DE 2.46X1.50 CHOLULA ALMOLOYA, MTS. TEXINTLA, SAN MATIAS COCOYOTLA, CALVARIO 18097 CONSTRUCCION DE SAN PEDRO SAN CRISTOBAL 249,580.50 PUEBLA 299.12 M2 1118 PERSONAS BIBLIOTECA CHOLULA TEPONTLA 18100 MEJORAMIENTO DE BARDA PERIMETRAL EN EL SAN PEDRO SAN MATIAS JARDIN DE NIÑOS IGNACIO 264,995.58 PUEBLA 542.73 240 PERSONAS CHOLULA COCOYOTLA MANUEL ALTAMIRANO CLAVE 21DJN0100S SAN DIEGO CUACHAYOTLA, 18105 CONSTRUCCION DE SANTA BARBARA CUARTO PARA BAÑOS TIPO SAN PEDRO ALMOLOYA, SANTA 1,489,905.51 PUEBLA 20 MODULOS 80 PERSONAS DE UNA SECCION DE CHOLULA MARIA 2.46X1.50 MTS. -

Hironymousm16499.Pdf

Copyright by Michael Owen Hironymous 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Michael Owen Hironymous certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio Committee: Julia E. Guernsey, Supervisor Frank K. Reilly, III, Co-Supervisor Brian M. Stross David S. Stuart John M. D. Pohl Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio by Michael Owen Hironymous, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2007 Dedication Al pueblo de Santa Maria Ixcatlan. Acknowledgements This dissertation project has benefited from the kind and generous assistance of many individuals. I would like to express my gratitude to the people of Santa María Ixcatlan for their warm reception and continued friendship. The families of Jovito Jímenez and Magdaleno Guzmán graciously welcomed me into their homes during my visits in the community and provided for my needs. I would also like to recognize Gonzalo Guzmán, Isabel Valdivia, and Gilberto Gil, who shared their memories and stories of years past. The successful completion of this dissertation is due to the encouragement and patience of those who served on my committee. I owe a debt of gratitude to Nancy Troike, who introduced me to Oaxaca, and Linda Schele, who allowed me to pursue my interests. I appreciate the financial support that was extended by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of Texas and FAMSI. -

La Arquitectura Mendicante Novohispana Del Siglo Xvi: Evolución Constructiva

La arquitectura mendicante novohispana del siglo xvi: evolución constructiva Mendicant architecture in new Spain in the 16th century and its evolution Espinosa Spínola, Gloria* BIBLID [0210-962-X(l 996); 27; 55-63] RESUMEN En el primer cuarto del siglo XVI se produjo la incorporación de las tierras mexicanas a los dominios de la Corona Española. Entre los mecanismos aplicados en el proceso de colonización destacó el proceso de conversión y evangelización de la población autóctona llevado a cabo por las órdenes mendicantes. Tomando como referencia la actividad constructiva de dichas órdenes, este texto plantea una serie de reflexiones sobre la evolución arquitectónica de los edificios conventuales durante el Quinientos. Palabras clave: Ordenes mendicantes; Arquitectura religiosa; Conventos; Templos; Arquitectura colonial; Capillas abiertas; México; Nueva España; S. 16. ABSTRACT During the first quarter of the 16th century lands in Mexico were incorporated into those owned by the Spanish Crown. Among the methods used in the colonization process was that of the conversion and evangelization of the native population which was carried out by the mendicant orders. Taking as her starting point the building undertaken by these orders, the author offers a series of reflections on the architectural development of convents and monasteries during the 1500s. Key words: Mendicant orders; Religious architecture; Convents; Monasteries; Churches: Colonial architecture; Open chapels; Mexico; New Spain; 16th century. La conquista de la ciudad de México-Tenochtitlán en agosto 1521 activó una serie de mecanismos políticos, económicos, sociales y culturales con la finalidad de implantar el orden colonial en el que fue virreinato de Nueva España. Lógicamente, esta metamorfosis cultural requería una nueva imagen urbana y arquitectónica que representara al nuevo sistema de poder en los territorios conquistados. -

Muigel Leon Portilla Y La Interpretacion Del Mito En

Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas Maestría en Historia (Opción Historia de México) Miguel León-Portilla y la interpretación del mito en las ediciones mexicanas de La filosofía náhuatl estudiada en sus fuentes. 1956-2006 Un análisis historiográfico. Tesis Que para optar por el grado de Maestro en Historia (Opción Historia de México) Presenta Cruz Alberto González Díaz Director de Tesis: Dr. Gerardo Sánchez Díaz Morelia, Michoacán, México. Junio 2011. UNIVERSIDAD MICHOACANA DE SAN NICOLÁS DE HIDALGO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES HISTÓRICAS MAESTRÍA EN HISTORIA (OPCIÓN HISTORIA DE MÉXICO) MIGUEL LEÓN-PORTILLA Y LA INTERPRETACIÓN DEL MITO EN LAS EDICIONES MEXICANAS DE LA FILOSOFÍA NÁHUATL ESTUDIADA EN SUS FUENTES. 1956-2006. UN ANÁLISIS HISTORIOGRÁFICO (Línea de investigación: Historiografía Mexicana y Teoría de la Historia) POR CRUZ ALBERTO GONZÁLEZ DÍAZ DIRECTOR: DR. GERARDO SÁNCHEZ DÍAZ MORELIA, MICHOACÁN. MAYO 2011 Para Álvaro Ochoa Serrano, Cuyas Palabras Nunca Muestran la Totalidad del Camino… Sólo Poseen La Bondad Necesaria Para No Dejarte Solo En Medio De La Oscuridad Quiero una imprevisible historia como lo es el curso de nuestras mortales vidas… susceptible de sorpresas y accidentes, de venturas y desventuras… una historia de atrevidos vuelos y siempre en vilo como nuestro amores… Edmundo O’ Gorman, Fantasmas en la narrativa historiográfica. ÍNDICE PROEMIO, 7 AGRADECIMIENTOS, 10 INTRODUCCIÓN, 12 Justificación, 12 Balance historiográfico, 18 Apreciaciones generales sobre el historiador Miguel León-Portilla y su obra, 19 Características de su obra, 21 Influencias historiográficas, filosóficas y dramatúrgicas, 28 Valoración sobre los métodos y procedimientos, 29 Percepción sobre los resultados e interpretaciones ofrecidas, 33 El planteamiento del problema, 46 Preguntas de investigación, 50 Hipótesis, 51 Marco teórico y propuesta metodológica, 52 Estructura de la investigación, 52 CAPÍTULO UNO. -

Poster/Flyer

25th-26th September 2013 27th-28th September 2013 International conference 2nd Forum on Iconography and workshop in Mesoamerica THE COIXTLAHUACA VALLEY, OAXACA, MEXICO TIME AND SPACE IN MESOAMERICA Current Research in Archaeology, History, Ethnology and Document Analysis Meeting Place Ethnologisches Museum - Staatliche Museen Berlin│Dahlem Museen │Lansstraße 8 │14195 Berlin U-Bhf. Dahlem Dorf (U3) │Bus M11, X 83, 101, 110 Contact Prof. Dr. Viola König │Director Ethnologisches - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin │Arnimallee 27 │ 14195 Berlin Phone: +49 030 8301-226/-231 │Fax: +49 030 8301-506 │ [email protected] │ www.smb.museum/em [email protected] International conference and workshop. September 25 and 26, 2013 techniques. His unusual background in archaeology, art history, and Ethnologisches Museum, Lansstraße 8, 14195 Berlin media production have taken him from museum exhibition design and development with the Walt Disney Company's Department of Cultural THE COIXTLAHUACA VALLEY, OAXACA, MEXICO Affairs to Princeton University where he served as the first Peter Jay Current Research in Archaeology, History, Ethnology and Sharp Curator and Lecturer in the Art of the Ancient Americas. Most Document Analysis recently, John Pohl curated the exhibition “The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire” for the Getty Villa Museum and is currently developing Wednesday, September 25, 2013 “Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico” for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Dallas Museum 7.30pm of Art. He is the author of the FAMSI website 'John Pohl's Mesoamerica', Foyer 1st floor and was co-author of Kevin Costner's '500 Nations'.