3 0 APR 2018 and STATE of VICTORIA the REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS for the ATTORNEY-GENERAL for the STATE of QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Environment Is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights

Advance Copy THE ENVIRONMENT IS ALL RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS, CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS RACHEL PEPPER* AND HARRY HOBBS† Te relationship between human rights and environmental rights is increasingly recognised in international and comparative law. Tis article explores that connection by examining the international environmental rights regime and the approaches taken at a domestic level in various countries to constitutionalising environmental protection. It compares these ap- proaches to that in Australia. It fnds that Australian law compares poorly to elsewhere. No express constitutional provision imposing obligations on government to protect the envi- ronment or empowering litigants to compel state action exists, and the potential for draw- ing further constitutional implications appears distant. As the climate emergency escalates, renewed focus on the link between environmental harm and human harm is required, and law and policymakers in Australia are encouraged to build on existing law in developing broader environmental rights protection. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 II Human Rights-Based Environmental Protections ................................................... 8 A International Environmental Rights ............................................................. 8 B Constitutional Environmental Rights ......................................................... 15 1 Express Constitutional Recognition .............................................. -

A Case for Structured Proportionality Under the Second Limb of the Lange Test

THE BALANCING ACT: A CASE FOR STRUCTURED PROPORTIONALITY UNDER THE SECOND LIMB OF THE LANGE TEST * BONINA CHALLENOR This article examines the inconsistent application of a proportionality principle under the implied freedom of political communication. It argues that the High Court should adopt Aharon Barak’s statement of structured proportionality, which is made up of four distinct components: (1) proper purpose; (2) rational connection; (3) necessity; and (4) strict proportionality. The author argues that the adoption of these four components would help clarify the law and promote transparency and flexibility in the application of a proportionality principle. INTRODUCTION Proportionality is a term now synonymous with human rights. 1 The proportionality principle is well regarded as the most prominent feature of the constitutional conversation internationally.2 However, in Australia, the use of proportionality in the context of the implied freedom of political communication has been plagued by confusion and controversy. Consequently, the implied freedom of political communication has been identified as ‘a noble and idealistic enterprise which has failed, is failing, and will go on failing.’3 The implied freedom of political communication limits legislative power and the common law in Australia. In Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 4 the High Court unanimously confirmed that the implied freedom5 is sourced in the various sections of the Constitution which provide * Final year B.Com/LL.B (Hons) student at the University of Western Australia. With thanks to Murray Wesson and my family. 1 Grant Huscroft, Bradley W Miller and Grégoire Webber, Proportionality and the Rule of Law (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 1. -

The Commission's Submission

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CANBERRA REGISTRY No. C12 of 2018 BETWEEN: COMCARE Appellant HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA and FILED 12 DEC 2018 10 MS MICHAELA BANERTI THE REGISTRY SYDNEY Respondent SUBMISSIONS OF THE AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SEEKING LEAVE TO APPEAR AS AMICUS CURIAE PART I: CERTIFICATION 1. It is certified that this submission is in a form suitable for publication on the internet. 20 PART II: BASIS OF LEAVE TO APPEAR 2. The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) seeks leave to appear as amicus curiae to make submissions in support of the Respondent (Banerji). The Court's power to grant leave derives from the inherent or implied jurisdiction given by Ch III of the Constitution and s 30 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART III: REASONS FOR LEAVE 3. Leave should be given to the AHRC for the following reasons. 4. First, the submissions advanced by the AHRC are not otherwise advanced by the parties. Without the submissions, the issues before the Court are otherwise unlikely to receive full or adequate treatment: cf Wurridjal v The Commonwealth (2009) 237 CLR 309 at Australian Human Rights Commission Contact: Graeme Edgerton Level 3, 175 Pitt Street Telephone: (02) 8231 4205 Sydney NSW 2000 Email: [email protected] Date of document: 12 December 2018 File ref: 2018/179 -2- 312-3. The Commission’s submissions aim to assist the Court in a way that it may not otherwise be assisted: Levy v State of Victoria (1997) 189 CLR 579 at 604 (Brennan CJ). 5. Secondly, the proposed submissions are brief and limited in scope. -

2 8 MAR 2017 the STATE of TASMANIA the REGISTRY CANBERRA Defendant

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No. H3 of2016 HOBART REGISTRY BETWEEN: ROBERTJAMESBROVVN First Plaintiff and 10 JESSICA ANNE WILLIS HOYT P.i';H COUPJ_Qf AUSTRALIA Second Plaintiff FILED and 2 8 MAR 2017 THE STATE OF TASMANIA THE REGISTRY CANBERRA Defendant ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS OF THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL FOR 20 THE STATE OF QUEENSLAND {INTERVENING) PART I: Internet publication 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PARTII: Basis of intervention 30 2. The Attorney-General for the State of Queensland ('Queensland') intervenes in these proceedings in support of the defendant pursuant to s 78A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART Ill: Reasons why leave to intervene should be granted 3. Not applicable. 40 Intervener' s submissions MrGRCooper Filed on behalf of the Attorney-General for the CROWN SOLICITOR State of Queensland (intervening) 11 tb Floor, State Law Building Form 27C 50 Ann Street, Brisbane 4000 Dated: 28 March 2017 Per Wendy Ussher Telephone 07 3239 6328 Ref PL8/ATT110/3460/UWE Facsimile 07 3239 3456 Document No: 7069966 PART IV: Statutory provisions 4. Queensland adopts the statement of relevant statutory provisions set out in Annexure A to the plaintiffs' submissions. PART V: Submissions SummaJy 5. Queensland adopts the submissions of the defendant. Queensland's submissions are 10 limited to the use of a structured proportionality test in the context of the implied freedom of political communication as expressly applied by the majority in McCloy v NewSouth Wales. 1 6. Respectfully, Queensland submits that a structured proportionality test is not an apt test to detennine the constitutional validity of legislation in Australia. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

The Normativity of the Principle of Legality

THE NORMATIVITY OF THE PRINCIPLE OF LEGALITY B RENDAN LIM* The constitutional justification for the principle of legality has been transformed. Its original basis in a positive claim about authentic legislative intention has been repudiat- ed. Statutes today are so far-reaching that it would be wrong to suppose any actual improbability in legislative intentions to abrogate common law rights. Two rival justifications for the principle have emerged in response. One is a refined positive claim: legislatures do not intend to abrogate ‘fundamental’ rights. The other is a normative claim: courts should attribute an intention not to abrogate rights in order to improve the political process. Distinguishing these justifications answers the vexed question of which rights engage the principle of legality. ‘Fundamental’ rights, in the first claim, just are those rights that legislatures do not, in fact, intend to abrogate. The normativity of the second claim is engaged not by ‘fundamental’ rights, but by ‘vulnerable’ rights not adequately protected by the ordinary political process. ‘Vulnerable’ rights may originate not only in the common law but also in statutes. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 373 II The Principle of Legality Transformed .................................................................. 378 A Myth of Continuity ..................................................................................... 378 B Original Justification and -

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST and PLACE in BROWN V TASMANIA

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST AND PLACE IN BROWN v TASMANIA PATRICK EMERTON AND MARIA O’SULLIVAN* I INTRODUCTION Protest is an important means of political communication in a contemporary democracy. Indeed, a person’s right to protest goes to the heart of the relationship between an individual and the state. In this regard, protest is about power. On one hand, there is the power of individuals to act individually or a collective to communicate their concerns about the operation of governmental policies or business activities. On the other, the often much stronger power wielded by a state to restrict that communication in the public interest. As part of this, state authorities may seek to limit certain protest activities on the basis that they are disruptive to public or commercial interests. The question is how the law should reconcile these competing interests. In this paper, we recognise that place is often integral to protest, particularly environmental protest. In many cases, place will be inextricably linked to the capacity of protest to result in influence. This is important given that the central aim of protest is usually to be an agent of change. As a result, the purpose of any legislation which seeks to protect business activities from harm and disruption goes to the heart of contestations about protest and power. In a recent analysis of First Amendment jurisprudence, Seidman suggests that [t]here is an intrinsic relationship between the right to speak and the ownership of places and things. Speech must occur somewhere and, under modern conditions, must use some things for purposes of amplification. -

Before the High Court

Before the High Court Comcare v Banerji: Public Servants and Political Communication Kieran Pender* Abstract In March 2019 the High Court of Australia will, for the first time, consider the constitutionality of limitations on the political expression of public servants. Comcare v Banerji will shape the Commonwealth of Australia’s regulation of its 240 000 public servants and indirectly impact state and local government employees, cumulatively constituting 16 per cent of the Australian workforce. But the litigation’s importance goes beyond its substantive outcome. In Comcare v Banerji, the High Court must determine the appropriate methodology to apply when considering the implied freedom of political communication’s operation on administrative decisions. The approach it adopts could have a significant impact on the continuing development of implied freedom jurisprudence, as well as the political expression of public servants. I Introduction Australian public servants have long endured an ‘obligation of silence’.1 Colonial civil servants were subject to strict limitations on their ability to engage in political life.2 Following Federation, employees of the new Commonwealth of Australia were not permitted to ‘discuss or in any way promote political movements’.3 While the more draconian of these restrictions have been gradually eased, limitations remain on the political expression of public servants. Until now, these have received surprisingly little judicial scrutiny. Although one of the few judgments in this field invalidated the impugned regulation,4 the Australian Public Service (‘APS’) has continued to limit the speech of its employees. * BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) (ANU); Legal Advisor, Legal Policy & Research Unit, International Bar Association, London, England. -

Judicial Independence, and the Separation of Judicial Power Doctrine: a Uniquely Australian Approach

‘Liberty’, Judicial Independence, and the Separation of Judicial Power Doctrine: A Uniquely Australian Approach Aman Gaur The separation of the judicial function from the other functions of government advances two constitutional objectives: the guarantee of liberty and, to that end, the independence of Ch III judges. Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey, McHugh, Gummow JJ articulating ‘the Wilson proposition’ in Wilson v Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Affairs1 Abstract The nature of the Australian Constitution means that it provides only for a separation of powers between the legislature and executive working as one in the Westminster Parliament and the unelected judiciary. This paper considers whether this doctrine of separation of (judicial) powers achieves, as argued by the High Court, the ‘constitutional objectives’ of an independent judiciary and, in consequence, ‘the guarantee of liberty’. After analysing the nuances of political terms such as "liberty" and the dynamic rationales of Australian federalism, this paper submits that the doctrine does advance a practical degree of judicial independence which facilitates a species of individual liberty under the Constitution. However the paper concludes by critiquing recent High Court decisions that have increasingly curtailed this ‘liberty’ through narrow judicial methodology, weakened notions of ‘judicial power’ and overt deference to parliament. 1 (1996) 189 CLR 1, 11 (‘Wilson’). 153 The ANU Undergraduate Research Journal Introduction This paper submits that the separation of judicial power principles advance a practical degree of judicial independence which facilitates a limited but increasingly curtailed ‘guarantee’ of republican ‘liberty’ for individuals under the Australian Constitution.2 Section I will articulate the Constitution’s ‘liberty’ to clarify and focus the analysis. -

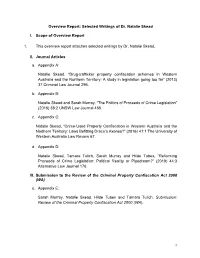

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead I. Scope of Overview Report 1. This overview report attaches selected writings by Dr. Natalie Skead. II. Journal Articles a. Appendix A: Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. b. Appendix B: Natalie Skead and Sarah Murray, “The Politics of Proceeds of Crime Legislation” (2015) 38:2 UNSW Law Journal 455. c. Appendix C: Natalie Skead, “Crime-Used Property Confiscation in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: Laws Befitting Draco’s Axones?” (2016) 41:1 The University of Western Australia Law Review 67. d. Appendix D: Natalie Skead, Tamara Tulich, Sarah Murray and Hilde Tubex, “Reforming Proceeds of Crime Legislation: Political Reality or Pipedream?” (2019) 44:3 Alternative Law Journal 176. III. Submission to the Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA) e. Appendix E: Sarah Murray, Natalie Skead, Hilde Tubex and Tamara Tulich, Submission: Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA). 1 Appendix A Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. Appendix A Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far Dr Natalie Skead* Combating drug-related crime is a key focus of proceeds of crime legislation in Australia. Despite this clear focus only three Australian jurisdictions have introduced confiscation provisions levelled specifically at those involved in drug-related crimes: New South Wales, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory. -

Murdoch University School of Law Michael Olds This Thesis Is

Murdoch University School of Law THE STREAM CANNOT RISE ABOVE ITS SOURCE: THE PRINCIPLE OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT INFORMING A LIMIT ON THE AMBIT OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH Michael Olds This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Laws with Honours at Murdoch University in 2016 Word Count: 19,329 (Excluding title page, declaration, copyright acknowledgment, abstract, acknowledgments and bibliography) DECLARATION This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other University. Further, to the best of my knowledge or belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. _______________ Michael Olds ii COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s 51(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: ………………………………… Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Laws with Honours Thesis Title: The stream cannot rise above its source: The principle of Responsible Government informing a limit on the ambit of the Executive Power of the Commonwealth Author: Michael Olds Year: 2016 iii ABSTRACT The Executive Power of the Commonwealth is shrouded in mystery. Although the scope of the legislative power of the Commonwealth Parliament has been settled for some time, the development of the Executive power has not followed suit. -

Inquiry Into Government Advertising and Accountability with Amendments to Term of Reference (A)

The Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Government advertising and accountability December 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 0 642 71593 9 This document is prepared by the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Committee Senator Michael Forshaw (Chair) ALP, NSW Senator John Watson (Deputy Chair) LP, TAS Senator Carol Brown ALP, TAS Senator Mitch Fifield LP, NSW Senator Claire Moore ALP, QLD Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA Substitute member for this inquiry Senator Kim Carr ALP, VIC (replaced Senator Claire Moore from 22 June 2005) Former substitute member for this inquiry Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA (replaced Senator Aden Ridgeway 30 November 2004 to 30 June 2005) Former members Senator George Campbell (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator the Hon William Heffernan (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator Aden Ridgeway (until 30 June 2005) Senator Ursula Stephens (1 July to 13 September 2005) Participating members Senators Abetz, Bartlett, Bishop, Boswell, Brandis, Bob Brown, Carr, Chapman, Colbeck, Conroy, Coonan, Crossin, Eggleston, Evans, Faulkner, Ferguson, Ferris, Fielding, Fierravanti-Wells, Joyce, Ludwig, Lundy, Sandy Macdonald, Mason, McGauran, McLucas, Milne, Moore, O'Brien, Parry, Payne, Ray, Sherry, Siewert, Stephens, Trood and Webber. Secretariat Alistair Sands Committee Secretary Sarah Bachelard Principal Research Officer Matt Keele Research Officer Alex Hodgson Executive Assistant Committee address Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee SG.60 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3530 Fax: 02 6277 5809 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate_fpa iii iv Terms of Reference On 18 November 2004, the Senate referred the following matter to the Finance and Public Administration References Committee for inquiry and report by 22 June 2005.