Judicial Independence, and the Separation of Judicial Power Doctrine: a Uniquely Australian Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs V PDWL [2020] FCA 394](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9662/minister-for-immigration-citizenship-migrant-services-and-multicultural-affairs-v-pdwl-2020-fca-394-259662.webp)

Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs V PDWL [2020] FCA 394

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs v PDWL [2020] FCA 394 File number: NSD 269 of 2020 Judge: WIGNEY J Date of judgment: 17 March 2020 Catchwords: MIGRATION – detention – power to detain – where first respondent refused a safe haven enterprise visa – where Administrative Appeals Tribunal granted a visa – where first respondent continued to be detained – application for a writ in the nature of habeas corpus – whether detention unlawful – interlocutory relief granted Legislation: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) ss 24AB, 34AB Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth) ss 43, 43(1), 43(1)(c)(ii), 43(5A), 43(5B), 43(6), 44 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 23 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 5.04(1), 5.04(3) Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) ss 39B, 39B(1), 39B(1A)(c) Migration Act 1958 (Cth) ss 13, 14, 36, 36(1C), 43(5A), 43(6), 65, 189, 189(1), 196, 196(1), 196(1)(c), 476A, 476A(1), 500(1)(b), 500(4), 501, 501(1), 501(6), 501(6)(d)(i) Cases cited: Al-Kateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562 Alsalih v Manager Baxter Immigration Detention Facility (2004) 136 FCR 291; FCA 352 BAL19 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCA 2189 Commonwealth Bank Officers Superannuation Corporation Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2005) 148 FCR 427; FCAFC 244 Matete v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2009] FCA 187 Minister for Home Affairs v CSH18 [2019] FCAFC 80 Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Bhardwaj (2002) 209 CLR 597 Minister for Immigration and Multicultural -

The Normativity of the Principle of Legality

THE NORMATIVITY OF THE PRINCIPLE OF LEGALITY B RENDAN LIM* The constitutional justification for the principle of legality has been transformed. Its original basis in a positive claim about authentic legislative intention has been repudiat- ed. Statutes today are so far-reaching that it would be wrong to suppose any actual improbability in legislative intentions to abrogate common law rights. Two rival justifications for the principle have emerged in response. One is a refined positive claim: legislatures do not intend to abrogate ‘fundamental’ rights. The other is a normative claim: courts should attribute an intention not to abrogate rights in order to improve the political process. Distinguishing these justifications answers the vexed question of which rights engage the principle of legality. ‘Fundamental’ rights, in the first claim, just are those rights that legislatures do not, in fact, intend to abrogate. The normativity of the second claim is engaged not by ‘fundamental’ rights, but by ‘vulnerable’ rights not adequately protected by the ordinary political process. ‘Vulnerable’ rights may originate not only in the common law but also in statutes. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 373 II The Principle of Legality Transformed .................................................................. 378 A Myth of Continuity ..................................................................................... 378 B Original Justification and -

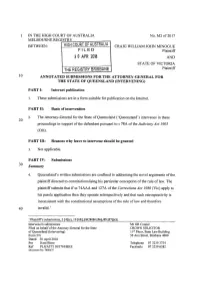

3 0 APR 2018 and STATE of VICTORIA the REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS for the ATTORNEY-GENERAL for the STATE of QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No. M2 of2017 MELBOURNEREG~IS~T~R~Y--~~~~~~~ BETWEEN: HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CRAIG WILLIAM JOHN MINOGUE FILED Plaintiff 3 0 APR 2018 AND STATE OF VICTORIA THE REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS FOR THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL FOR THE STATE OF QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING) PART I: Internet publication I. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART 11: Basis of intervention 2. The Attorney-General for the State of Queensland ('Queensland') intervenes in these 20 proceedings in support of the defendant pursuant to s 78A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART Ill: Reasons why leave to intervene should be granted 3. Not applicable. PART IV: Submissions 30 Summary 4. Queensland's written submissions are confined to addressing the novel arguments of the plaintiff directed to constitutionalising his particular conception of the rule of law. The plaintiff submits that if ss 74AAA and 127A ofthe Corrections Act 1986 (Vie) apply to his parole application then they operate retrospectively and that such retrospectivity is inconsistent with the constitutional assumptions of the rule of law and therefore 40 invalid. 1 1 Plaintiffs submissions, 2 [4](c), 19 [68]; (SCB 84(36), 85(37)(c)). Intervener's submissions Mr GR Cooper Filed on behalf of the Attorney-General for the State CROWN SOLICITOR of Queensland (Intervening) 11th Floor, State Law Building Form 27c 50 Ann Street, Brisbane 4000 Dated: 30 April2018 Per Kent Blore Telephone 07 3239 3734 Ref PL8/ATT110/3710/BKE Facsimile 07 3239 6382 Document No: 7880475 5. Queensland's primary submission is that ss 74AAA and 127 A ofthe Corrections Act do not operate retrospectively as they merely prescribe criteria for the Board to apply in the future. -

Submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Committee Inquiry Into The

Submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Committee Inquiry into the administration and operation of the Migration Act By Angus Francisi Introduction This submission focuses on the first term of reference of the Senate Legal and Constitutional Committee Inquiry into the administration and operation of the Migration Act. In particular, this submission focuses on the administration and operation of the detention and removal powers of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (‘MA’). The Cornelia Rau and Vivian Solon cases highlight the failure of the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (‘DIMIA’) to properly administer the detention and removal powers found in the MA. According to Mick Palmer, the head of the government initiated inquiry into the detention of Cornelia Rau, this is a result of inadequate training, insufficient internal controls, lack of management oversight and review, a failure of co-ordination between Federal, State and non-government agencies, as well as a culture within the compliance and detention sections of DIMIA that is ‘overly self-protective and defensive’.ii The Palmer Report unearthed what has laid stagnant on the surface of earlier public inquiries into the operation of the MA: an attitude within government that the powers to detain and remove unlawful non-citizens are wide and unfettered. This attitude is evident in the way in which the detention and removal powers in the MA are often exercised without due regard or concern for the individual subject to those powers. This position is unlikely to change, even if, as inquiry head Mick Palmer recommended, effective personnel and cultural change takes place within DIMIA. -

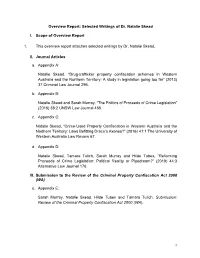

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead I. Scope of Overview Report 1. This overview report attaches selected writings by Dr. Natalie Skead. II. Journal Articles a. Appendix A: Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. b. Appendix B: Natalie Skead and Sarah Murray, “The Politics of Proceeds of Crime Legislation” (2015) 38:2 UNSW Law Journal 455. c. Appendix C: Natalie Skead, “Crime-Used Property Confiscation in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: Laws Befitting Draco’s Axones?” (2016) 41:1 The University of Western Australia Law Review 67. d. Appendix D: Natalie Skead, Tamara Tulich, Sarah Murray and Hilde Tubex, “Reforming Proceeds of Crime Legislation: Political Reality or Pipedream?” (2019) 44:3 Alternative Law Journal 176. III. Submission to the Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA) e. Appendix E: Sarah Murray, Natalie Skead, Hilde Tubex and Tamara Tulich, Submission: Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA). 1 Appendix A Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. Appendix A Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far Dr Natalie Skead* Combating drug-related crime is a key focus of proceeds of crime legislation in Australia. Despite this clear focus only three Australian jurisdictions have introduced confiscation provisions levelled specifically at those involved in drug-related crimes: New South Wales, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory. -

Refugee Law-Recent Legislative Developments

Department of the INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Parliamentary Library Current Issues Brief No. 5 2001–02 Refugee Law—Recent Legislative Developments ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2001 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2001 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 5 2001–02 Refugee Law—Recent Legislative Developments Nathan Hancock Law and Bills Digest Group 18 September 2001 Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Professor John McMillan of the Australian National University for his assistance in preparing this Current Issues Brief. -

The Nauru 10: the Habeas Corpus Challenge

The Nauru 10 The Habeas Corpus Challenge Asylum Seekers as Victims of the International System. UNHCR Global Report 2013. 45.2 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. 15.4 million refugees, 937,00 asylum seekers and 28.8 internally displaced people. 55 per cent come from just five war-affected countries, namely Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Syria and Sudan. Women and girls made up 48% of the refugees population. 46 per cent of refugees are children below 18 years. Developing Countries host 80% of the refugee population. UNHCR Total Budget $US 3.07 Billion. Asylum Seekers as Victims of the International System. Australia’s Refugee Statistics. The current intake of refugees is 20,000 for 2013. 23,000 people displaced per day worldwide – more than the total claiming asylum in Australia per year. 12,194 asylum seekers have arrived on 180 boats in 2013. 93.5% were found to be refugees in 2010-11. Australia hosts 30,083 Refugees or 0.3% of the global population. Out of 88,600 refugees resettled worldwide in 2012, Australia received 5,900. Australia is ranked 49th in terms of hosting. However, Australia was 11th for unprocessed claims. Total Costs of Detention and Offshore Programs - $2.97 billion for 2013-14. The Nauru 10 - The Human Face of the Statistics. The Story of JHB. JHB is a national of Iran of Arab ethnicity. JHB arrived in Australian territory by boat, SIEV 431, on or around 1 September 2012 and was taken to Christmas Island and then forcibly deported to Nauru on 24 September 2012. JHB is seeking protection due to his membership of a political party that stands for the rights of Arabs in Ahwaz. -

In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows

Washington International Law Journal Volume 12 Number 1 Symposium: Australia's Tampa Incident: The Convergence of International and Domestic Refugee and Maritime Law 1-1-2003 In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows Mary Crock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Crock, In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows, 12 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 49 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol12/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright C 2003 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association IN THE WAKE OF THE TAMPA: CONFLICTING VISIONS OF INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE LAW IN THE MANAGEMENT OF REFUGEE FLOWS Mary Crockt Abstract: The Australian Government's decision in August 2001 to close its doors to a maritime Good Samaritan, Norwegian Captain Rinnan, his crew, and 433 Afghan and Iraqi rescuees, provided a curious contrast to the image of humanity, generosity, and openness that Australia tried so hard to foster during the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. Victims or villains according to how the facts and the law are characterized, the MI/V Tampa rescuers represented for lawyers the intersection of a variety of areas of law and a clash of legal principles. -

Open Justice: Concepts and Judicial Approaches

The Peter A. Allard School of Law Allard Research Commons Faculty Publications Allard Faculty Publications 2012 Open Justice: Concepts and Judicial Approaches Emma Cunliffe Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Citation Details Cunliffe Emma, "Open Justice: Concepts and Judicial Approaches" (2012) 40 Fed L Rev 385. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Allard Faculty Publications at Allard Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Allard Research Commons. OPEN JUSTICE: CONCEPTS AND JUDICIAL APPROACHES Emma Cunliffe* ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increase in the number and scope of non-publication orders and other limits on open justice, an increase in the number of statutes that regulate or threaten open justice and the articulation of an Australian constitutional principle (of institutional integrity) that has the potential to protect some aspects of open justice. The purposes and values of open justice are, however, rarely examined in a comprehensive or theoretically-informed manner. This article provides a theory of open justice which accounts for its heterogeneous nature. Australian judicial approaches to the substance, limits and constitutional dimensions of open justice are analysed in light of the purposes and values of open justice, and a comparison with the much more coherent Canadian approach is supplied. The author concludes that threats to open justice are best managed by an analytical framework which systematically identifies both the benefits of open justice and the countervailing values that are at stake in a given case, and which seeks to provide maximum protection to all of these values on a case-by-case basis. -

Originalism in Constitutional Interpretation

FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL INFLUENCES ON STATE JUDICIAL REVIEW Matthew Groves* I INTRODUCTION Since the late 1990s it has become increasingly clear that the Commonwealth Constitution is the dominant influence upon judicial review of administrative action in Australia. The Constitution provides for a minimum entrenched provision of judicial review by recognising and protecting the supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court. This protection comes at a price because the separation of powers doctrine and the division and allocation of functions it fosters impose many limits upon the reach and content of judicial review of administrative action. This protective and restrictive effect of the separation of powers upon judicial review of administrative action arguably reflects a wider tension in the separation of powers, in which the powers and limits of each arm of government are balanced in a wider sense. The extent to which these competing principles apply to judicial review at the State level has long been unclear. There seemed good reason why judicial review at the State level should not be subject to the restrictions that have arisen at the federal level. After all, the various State constitutions did not adopt an entrenched separation of powers like that of the Commonwealth Constitution.1 The lack of any entrenched separation of _____________________________________________________________________________________ * Law Faculty, Monash University. This article is a revised version of a paper presented to the New South Wales chapter of the Australian Association of Constitutional Law in 2010. Thanks are due to Mark Aronson and reviewers for helpful comments. 1 This point was long acknowledged in different ways. Sometimes it was an acceptance that the overall structure or particular provisions of a State constitution did not provide a basis to hold or imply a principle of separation of powers. -

Kevin Lindgren AM QC – Kable's Case and the Rule Of

KABLE’S CASE AND THE RULE OF LAW The Hon Kevin Lindgren AM QC Formerly a judge of the Federal Court of Australia* Introduction The decision of the High Court of Australia in Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) (1996) 189 CLR 51; 138 ALR 577; [1996] HCA 24 (Kable) has marked the beginning of an ongoing development in Australian constitutional law, with rule of law implications. The rule of law implies effective legal constraints on the exercise of power, including power derived from the operation of democratic processes. In the case of present concern, the law in question is that founded in the Australian Constitution, and the power in question is that of the democratically elected legislatures and governments of the Australian States. The Australian federation The importance of Kable can be understood only against the background of the Australian federal system. The Commonwealth of Australia came into existence on 1 January 1901 as a federation of six States (previously called “Colonies”). (Later, two mainland Territories were established upon being “carved out of” the territorial areas of certain States, but for present purposes I need say no more of their special position in the federation.) The Commonwealth Constitution (henceforth, simply the Constitution) is found in s 9 in the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, which is an act of the United Kingdom Parliament. The States have their own Constitution Acts, which are simply Acts of the Parliaments of the States. The State Constitutions can be amended by the State legislatures. * I am indebted to Nick Clark of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia for research assistance. -

Advisory Board

S U N B C E RUCE LUM THE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION ADVISORY BOARD EEmeritusmeritus PProfessorrofessor W R CCornishornish EEmeritusmeritus HHerchelerchel SSmithmith PProfessorrofessor ooff IIntellectualntellectual PPropertyroperty LawLaw UUniversityniversity ooff CCambridgeambridge UUnitednited KKingdomingdom PrJudgeofesso Jr RJ RCrawford Crawford WhewInternationalell Professor Courtof Int eofrn Justiceational Law University of Cambridge The HonUn iProfessorted Kingd Jo mJ Doyle Former Chief Justice SupremeEmeritus Court Profe sofso Southr M J DAustraliaetmold Adelaide Law School EmeritusThe Uni vProfessorersity of AR dGraycarelaide SydneySouth LawAus tSchoolralia The University of Sydney The HNewon P Southrofess oWalesr J J Doyle Former Chief Justice SupremeProfessor Court of JS Vou Orthth Australia William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law The UniversityEmerit ofus NorthProfes Carolinasor R Gr aaty cChapelar Hill UnitedSydn Statesey Law of S Americachool The University of Sydney ProfessorNew Emerita South W Ra lJe Owenss Adelaide Law School The PUniversityrofessor J ofV OAdelaiderth William RandSouth Ken aAustralian Jr Professor of Law The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill EmeritusUnited S Professortates of A Im Shearererica Sydney Law School EmTheeri Universitytus Profess oofr ISydney Shearer SNewydne ySouth Law WalesSchool The University of Sydney ProfessorNew S oJu Mth WilliamsWales Adelaide Law School TheProfessor University J M ofWilliams Adelaide AdelaideSouth AustraliaLaw School The University