2018 Winterton Lecture Constitutional Interpretation James Edelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Environment Is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights

Advance Copy THE ENVIRONMENT IS ALL RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS, CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS RACHEL PEPPER* AND HARRY HOBBS† Te relationship between human rights and environmental rights is increasingly recognised in international and comparative law. Tis article explores that connection by examining the international environmental rights regime and the approaches taken at a domestic level in various countries to constitutionalising environmental protection. It compares these ap- proaches to that in Australia. It fnds that Australian law compares poorly to elsewhere. No express constitutional provision imposing obligations on government to protect the envi- ronment or empowering litigants to compel state action exists, and the potential for draw- ing further constitutional implications appears distant. As the climate emergency escalates, renewed focus on the link between environmental harm and human harm is required, and law and policymakers in Australia are encouraged to build on existing law in developing broader environmental rights protection. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 II Human Rights-Based Environmental Protections ................................................... 8 A International Environmental Rights ............................................................. 8 B Constitutional Environmental Rights ......................................................... 15 1 Express Constitutional Recognition .............................................. -

The Toohey Legacy: Rights and Freedoms, Compassion and Honour

The Toohey Legacy: rights and freedoms, compassion and honour Introduction This year is the 25th anniversary of the Mabo decision, in which the late John Toohey played a significant role. It is fitting, therefore, that I commence with a reference to Malo’s Law which was oft repeated during the evidence in that case: Malo tag mauki mauki, Teter mauki mauki. Malo tag aorir aorir, Teter aorir aorir. Malo tag tupamait tupamait, Teter tupamait tupamait Malo keeps his hands to himself; he does not touch what is not his. He does not permit his feet to carry him Towards another man’s property. His hands are not grasping He holds them back. He does not wander from his path. He walks on tiptoe, silent, careful, Leaving no sign to tell that This is the way he took. Malo is the God, in the form of an octopus, who gave the Meriam people the laws they live by. He laid his tentacles down on the Island of Mer, creating the 1 8 tribes of Mer and he gave them the rule that they should not trespass on one another’s lands. Consistently with Malo’s law, I acknowledge that this event is occurring on the traditional land of the Whadjuk People of the Nyungar Nation. I acknowledge their elders and thank them for welcoming us onto this site alongside the Derbal Yerrigan1. Eleanor Roosevelt said that “great minds discuss ideas, average minds discuss events, small minds discuss people”. The focus of this address is upon the ideas discussed by the Honourable John Leslie Toohey AC QC, expressed in his judgments and occasional lectures. -

The Supreme Court of Victoria

ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL Annual Report Supreme Court a SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA 2016-17 of Victoria SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17ANNUAL Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Letter to the Governor September 2017 To Her Excellency Linda Dessau AC, Governor of the state of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. Dear Governor, We, the judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria, have the honour of presenting our Annual Report pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial year 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Yours sincerely, Marilyn L Warren AC The Honourable Chief Justice Supreme Court of Victoria Published by the Supreme Court of Victoria Melbourne, Victoria, Australia September 2017 © Supreme Court of Victoria ISSN 1839-6062 Authorised by the Supreme Court of Victoria. This report is also published on the Court’s website: www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au Enquiries Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Tel: 03 9603 6111 Email: [email protected] Annual Report Supreme Court 1 2016-17 of Victoria Contents Chief Justice foreword 2 Court Administration 49 Discrete administrative functions 55 Chief Executive Officer foreword 4 Appendices 61 Financial report 62 At a glance 5 Judicial officers of the Supreme Court of Victoria 63 About the Supreme Court of Victoria 6 2016-17 The work of the Court 7 Judicial activity 65 Contacts and locations 83 The year in review 13 Significant events 14 Work of the Supreme Court 18 The Court of Appeal 19 Trial Division – Commercial Court 23 Trial Division – Common Law 30 Trial Division – Criminal 40 Trial Division – Judicial Mediation 45 Trial Division – Costs Court 45 2 Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Chief Justice foreword It is a pleasure to present the Annual Report of the Supreme Court of Victoria for 2016-17. -

The University of Western Australia Law Review: the First Seventy Years

1 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA LAW REVIEW: THE FIRST SEVENTY YEARS MICHAEL BLAKENEY* I FOUNDATION The two oldest Australian university law journals are the UWA Law Review and the Queensland University Law Review, both founded in 1948. In his foreword to the first issue of the UWA Law Review the Hon. Sir John Dwyer, Chief Justice of Western Australia, noting the coming of age of the School of Law in the University of Western Australia, which had been established in 1927 and explained that “now in the enthusiasm of early maturity it has planned the publication of an Annual Law Review of a type and on a scale not hitherto attempted in any Australian University.” The Chief Justice in his foreword identified the desirable objectives of the Law Review. He wrote: It is too much to-day to expect statutory recognition, prompt and adequate, by legislatures almost exclusively preoccupied with economic questions. It is necessary to have a considerable body of informed opinion to show the needs and point the way; and the creation of such a body depends in turn on an explanation and understanding of our institutions, an exposition of the underlying principles of our laws and customs, an examination of their moral sources, a comparison with other legal systems, a criticism_ of applications and interpretations that may appear to be dubious. There is no better mode of achieving such ends than a Review devoted to such purposes, and this first number is a satisfactory step in the right direction. The example set in 1948 by the Universities of Western Australia and Queensland in establishing their law reviews was followed by the University of Sydney in 1953, when it established the Sydney Law Review and in 1957 with the establishment of the Melbourne University Law Review; the University of Tasmania Law Review in 1958; the Adelaide Law Review in 1960 and the Australian National University’s Federal Law Review in 1964. -

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST and PLACE in BROWN V TASMANIA

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST AND PLACE IN BROWN v TASMANIA PATRICK EMERTON AND MARIA O’SULLIVAN* I INTRODUCTION Protest is an important means of political communication in a contemporary democracy. Indeed, a person’s right to protest goes to the heart of the relationship between an individual and the state. In this regard, protest is about power. On one hand, there is the power of individuals to act individually or a collective to communicate their concerns about the operation of governmental policies or business activities. On the other, the often much stronger power wielded by a state to restrict that communication in the public interest. As part of this, state authorities may seek to limit certain protest activities on the basis that they are disruptive to public or commercial interests. The question is how the law should reconcile these competing interests. In this paper, we recognise that place is often integral to protest, particularly environmental protest. In many cases, place will be inextricably linked to the capacity of protest to result in influence. This is important given that the central aim of protest is usually to be an agent of change. As a result, the purpose of any legislation which seeks to protect business activities from harm and disruption goes to the heart of contestations about protest and power. In a recent analysis of First Amendment jurisprudence, Seidman suggests that [t]here is an intrinsic relationship between the right to speak and the ownership of places and things. Speech must occur somewhere and, under modern conditions, must use some things for purposes of amplification. -

3 0 APR 2018 and STATE of VICTORIA the REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS for the ATTORNEY-GENERAL for the STATE of QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No. M2 of2017 MELBOURNEREG~IS~T~R~Y--~~~~~~~ BETWEEN: HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CRAIG WILLIAM JOHN MINOGUE FILED Plaintiff 3 0 APR 2018 AND STATE OF VICTORIA THE REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS FOR THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL FOR THE STATE OF QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING) PART I: Internet publication I. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART 11: Basis of intervention 2. The Attorney-General for the State of Queensland ('Queensland') intervenes in these 20 proceedings in support of the defendant pursuant to s 78A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART Ill: Reasons why leave to intervene should be granted 3. Not applicable. PART IV: Submissions 30 Summary 4. Queensland's written submissions are confined to addressing the novel arguments of the plaintiff directed to constitutionalising his particular conception of the rule of law. The plaintiff submits that if ss 74AAA and 127A ofthe Corrections Act 1986 (Vie) apply to his parole application then they operate retrospectively and that such retrospectivity is inconsistent with the constitutional assumptions of the rule of law and therefore 40 invalid. 1 1 Plaintiffs submissions, 2 [4](c), 19 [68]; (SCB 84(36), 85(37)(c)). Intervener's submissions Mr GR Cooper Filed on behalf of the Attorney-General for the State CROWN SOLICITOR of Queensland (Intervening) 11th Floor, State Law Building Form 27c 50 Ann Street, Brisbane 4000 Dated: 30 April2018 Per Kent Blore Telephone 07 3239 3734 Ref PL8/ATT110/3710/BKE Facsimile 07 3239 6382 Document No: 7880475 5. Queensland's primary submission is that ss 74AAA and 127 A ofthe Corrections Act do not operate retrospectively as they merely prescribe criteria for the Board to apply in the future. -

Before the High Court

Before the High Court Comcare v Banerji: Public Servants and Political Communication Kieran Pender* Abstract In March 2019 the High Court of Australia will, for the first time, consider the constitutionality of limitations on the political expression of public servants. Comcare v Banerji will shape the Commonwealth of Australia’s regulation of its 240 000 public servants and indirectly impact state and local government employees, cumulatively constituting 16 per cent of the Australian workforce. But the litigation’s importance goes beyond its substantive outcome. In Comcare v Banerji, the High Court must determine the appropriate methodology to apply when considering the implied freedom of political communication’s operation on administrative decisions. The approach it adopts could have a significant impact on the continuing development of implied freedom jurisprudence, as well as the political expression of public servants. I Introduction Australian public servants have long endured an ‘obligation of silence’.1 Colonial civil servants were subject to strict limitations on their ability to engage in political life.2 Following Federation, employees of the new Commonwealth of Australia were not permitted to ‘discuss or in any way promote political movements’.3 While the more draconian of these restrictions have been gradually eased, limitations remain on the political expression of public servants. Until now, these have received surprisingly little judicial scrutiny. Although one of the few judgments in this field invalidated the impugned regulation,4 the Australian Public Service (‘APS’) has continued to limit the speech of its employees. * BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) (ANU); Legal Advisor, Legal Policy & Research Unit, International Bar Association, London, England. -

Newsletter-Vol09-Issue01-April 2018.Pub

MURDOCH LAW NEWSLETTER Vol. 9, Issue 1, May 2018 www.murdoch.edu.au/School-of-Law/ Inside this issue: Dean’s Award Ceremony 2 Community Engagement 11 Distinguished Alumni 6 Indigenous incarceration 14 Law Café Series 16 Retirement of Professor Neil Mcleod 7 New Colombo Program - Travel to India 19 Planning Symposium 8 made possible A Word from the Dean Habemus EBA! The Enterprise Bargaining process has finally come to a conclusion and it would seem that the finalizaon of the actual agreement is only a formality. This brings and end to a long process with considerable challenges on all sides. Let us not forget that a lot of people put in a lot of work to bring this to what looks to be a good end and thanks to all of them. The “good end” is the perfect segue to talk about the rerement of Professor Neil McLeod. Neil was a fixture at this Law School almost since its incepon and in the best possible sense an academic of the “old school”. Now, of course, some will say the world in general and the academic world in parcular are changing and “old school” is out and change is in. Really? Depends on what one wants to look at. Yes, there is the internet and the various new generaons of students, x, y, z, millennials and what not. But at the end of the day all knowledge and understanding enters the brain through ears and eyes and at the end of the day it is intensive engagement, reading, thinking and discourse that makes a good graduate, a good professional and a good academic and that kind of intensive engagement creates the ability to think crically and analycally. -

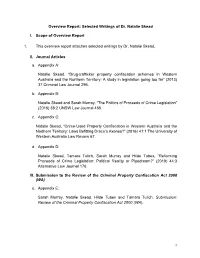

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead

Overview Report: Selected Writings of Dr. Natalie Skead I. Scope of Overview Report 1. This overview report attaches selected writings by Dr. Natalie Skead. II. Journal Articles a. Appendix A: Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. b. Appendix B: Natalie Skead and Sarah Murray, “The Politics of Proceeds of Crime Legislation” (2015) 38:2 UNSW Law Journal 455. c. Appendix C: Natalie Skead, “Crime-Used Property Confiscation in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: Laws Befitting Draco’s Axones?” (2016) 41:1 The University of Western Australia Law Review 67. d. Appendix D: Natalie Skead, Tamara Tulich, Sarah Murray and Hilde Tubex, “Reforming Proceeds of Crime Legislation: Political Reality or Pipedream?” (2019) 44:3 Alternative Law Journal 176. III. Submission to the Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA) e. Appendix E: Sarah Murray, Natalie Skead, Hilde Tubex and Tamara Tulich, Submission: Review of the Criminal Property Confiscation Act 2000 (WA). 1 Appendix A Natalie Skead, “Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far” (2013) 37 Criminal Law Journal 296. Appendix A Drug-trafficker property confiscation schemes in Western Australia and the Northern Territory: A study in legislation going too far Dr Natalie Skead* Combating drug-related crime is a key focus of proceeds of crime legislation in Australia. Despite this clear focus only three Australian jurisdictions have introduced confiscation provisions levelled specifically at those involved in drug-related crimes: New South Wales, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory. -

Volume 40, Number 1 the ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 1 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD Sydney Law School The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Charles Hamra, Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 1 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

The Toohey Legacy: Rights and Freedoms, Compassion and Honour

57 THE TOOHEY LEGACY: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS, COMPASSION AND HONOUR GREG MCINTYRE* I INTRODUCTION John Toohey is a person whom I have admired as a model of how to behave as a lawyer, since my first years in practice. A fundamental theme of John Toohey’s approach to life and the law, which shines through, is that he remained keenly aware of the fact that there are groups and individuals within our society who are vulnerable to the exercise of power and that the law has a role in ensuring that they are not disadvantaged by its exercise. A group who clearly fit within that category, and upon whom a lot of John’s work focussed, were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In 1987, in a speech to the Student Law Reform Society of Western Australia Toohey said: Complex though it may be, the relation between Aborigines and the law is an important issue and one that will remain with us;1 and in Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case)2 he reaffirmed what was said in the Tasmanian Dam Case,3 that ‘[t]he relationship between the Aboriginal people and the lands which they occupy lies at the heart of traditional Aboriginal culture and traditional Aboriginal life’. A University of Western Australia John Toohey had a long-standing relationship with the University of Western Australia, having graduated in 1950 in Law and in 1956 in Arts and winning the F E Parsons (outstanding graduate) and HCF Keall (best fourth year student) prizes. He was a Senior Lecturer at the Law School from 1957 to 1958, and a Visiting Lecturer from 1958 to 1965. -

Honouring Pro Bono Lawyering

2348 Honouring Pro Bono Lawyering The Victorian Bar Pro Bono Committee Reception in honour of the pro bono commitments of members of the Victorian Bar Melbourne, Victoria 2 April 2009. The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMB THE VICTORIAN BAR PRO BONO COMMITTEE RECEPTION IN HONOUR OF THE PRO BONO COMMITMENTS OF MEMBERS OF THE VICTORIAN BAR MELBOURNE, VICTORIA, 2 APRIL 2009. HONOURING PRO BONO LAWYERING The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG* SAVED FROM A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE One of the worst misfortunes that can befall a person in judicial office is to be an instrument of the miscarriage of justice. I know, because it happened to me. It is something I have to live with. In 2006, a bundle of appeal books landed on the desk of my chambers in Canberra. They concerned an appeal by Andrew Mallard. Special leave having been granted, Mr. Mallard was challenging orders of the Court of Appeal of Western Australia. Those orders had rejected his petition for the exercise of the royal prerogative of mercy, in respect of his conviction of murder more than a decade earlier. Very thorough submissions were filed on Mr. Mallard’s behalf by pro bono Counsel, Mr. Malcolm McCusker AO QC and Dr. James Edelman, members of the Western Australian Bar. As I read the papers, aspects of the case seemed *Justice of the High Court of Australia (1996-2009) 1 familiar. And then my attention was drawn to the fact that a decade earlier, Mr. Mallard had sought, and failed to obtain, special leave to appeal from an earlier panel in the High Court.