The Last Battle Royale: the Catalyst of Lepanto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antagonist Images of the Turk in Early Modern European Games

ANTI/THESIS 87 The earliest representation of the Turk in art appeared in Venetian Quattrocento ANTI-THESIS Antagonist paintings as a result of the increasing com- Images of mercial activities of Venice, which played a role as the main connection between the Turk in Europe and the Levant (Raby 17). The per- ception of the image of the Turk varied Early Modern depending on the conflicts between Venice and the Ottomans, usually pro- European Games voked by religious and political propa- ganda. Gentile Bellini’s circa 1480 portrait of Mehmed the Conqueror, who con- quered Constantinople, is one of such rare early examples that reflected an apprecia- tion of an incognito enemy before the early modern period, which had faded Ömer Fatih Parlak over the course of time as tensions increased. Bellini, who started a short- “The Turk” is a multifaceted concept that perspective to the image of the Turk by lived early Renaissance Orientalism, was emerged in the late Middle Ages in shedding light on its representations in commissioned by Mehmed II, whose pri- Europe, and has gained new faces over early modern European board games and vate patronage was “eclectic with a strong the course of time until today. Being pri- playing cards; thus, contributing to a nou- interest in both historical and contempo- marily a Muslim, the Turk usually con- velle scholarly interest on the image of rary Western culture” (Raby 7).1 The forma- noted the antichrist, infidel, and the ulti- the Turk. It argues that, belonging to a tion of the Holy League of 1571 against the mate enemy. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Painted by Titian 1551 PHILIP II KING OF SPAIN “ THE PRUDENT” Signature CONTENT AND LANGUAGE INTEGRATED LEARNING UNIT (UNIDAD DIDÁCTICA CLIL) 2017/18 HISTORY lrs Lourdes Ruiz Juana of Castile Philip “The Handsome” Maria of Aragon. Manuel I of Portugal 3rd DAUGTHER OF of Austria 4TH DAUGTHER OF Isabel and Ferdinand Isabel and Ferdinand Charles I of Spain Isabella of Portugal nd Born: 21 May 1527 1st wife 2 wife 3rd wife 4th wife Died: 13 September 1598 Maria Manuela Mary I of England Elizabeth Anna of Austria Philip II of Spain of Portugal “Bloody Mary” of Valois Spain, the Netherlands, Italian Territories & The Spanish Empire lrs 1527: Philip II of Spain was born in Palacio de Pimentel, Valladolid, which was the capital of the Spanish empire. In June 1561, Philip moved his court to Madrid making it the new capital city. Philip was a studious young boy, he learnt Spanish, Portuguese and Latin. 'The Baptism of Philip II' in Valladolid. He enjoyed hunting and sports as well as music. Historical ceiling preserved in Palacio de Pimentel (Valladolid) Also, he was trained in warfare by the . court [kɔːt] N corte Duke of Alba hunting [ˈhʌntɪŋ] N caza, cacería lrs warfare [ˈwɔːfɛər] N guerra, artes militares Look at this map. In 1554-55, Philip’s father, Charles I of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor abdicated in favour of his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand. Charles left all the territories in ORANGE to his son. After different battles and expeditions, Philip’s Empire would include all the territories in GREEN. That is, he took control of Portugal and its colonies in America, Africa and Asia. -

La Società Ligure Di Storia Patria Nella Storiografia Italiana 1857-2007

ATTI DELLA SOCIETÀ LIGURE DI STORIA PATRIA Nuova Serie – Vol. L (CXXIV) Fasc. II La Società Ligure di Storia Patria nella storiografia italiana 1857-2007 a cura di Dino Puncuh ** GENOVA MMX NELLA SEDE DELLA SOCIETÀ LIGURE DI STORIA PATRIA PALAZZO DUCALE – PIAZZA MATTEOTTI, 5 Indice degli « Atti » (1858-2009) del « Giornale Ligustico » (1874-1898) e del « Giornale storico e letterario della Liguria » (1900-1943) a cura di Davide Debernardi e Stefano Gardini Gli indici che seguono riportano gli scritti editi sulle pubblicazioni periodiche della Società: « Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria », 1858-2009 (ASLi,); « Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, serie del Risorgimento », 1923-1950 (ASLi, serie Risorgimento); « Giornale Ligu- stico », 1874-1898 (GL); « Giornale Storico e Letterario della Liguria », 1900-1908, 1925-1943 (GSLL). L’articolazione in più serie all’interno della singola testata è resa dalla sigla n.s.; per agevolare la consultazione, gli ordinali dei singoli volumi e dei loro fascicoli sono resi in nu- meri arabi. Il primo indice riporta gli scritti organizzati in ordine alfabetico per autore; gli scritti anonimi, gli atti congressuali, gli inventari archivistici e le edizioni documentarie costituisco- no voce principale alla stregua degli autori. All’interno della voce di ciascun autore gli scritti sono organizzati secondo il medesimo criterio, con in calce gli opportuni rimandi ad altre voci correlate: altri autori degli scritti in collaborazione, curatele, edizioni documentarie, etc. Ru- briche, rassegne bibliografiche e notizie di altri enti ed istituti sono elencate di seguito. Le rassegne bibliografiche sono ordinate tematicamente; l’indice degli scritti recensiti, attual- mente in fase di compilazione, sarà prossimamente fruibile on-line sul sito della Società. -

The Abandonment of Butrint: from Venetian Enclave to Ottoman

dining in the sanctuary of demeter and kore 1 Hesperia The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens Volume 88 2019 Copyright © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, originally pub- lished in Hesperia 88 (2019), pp. 365–419. This offprint is supplied for per- sonal, non-commercial use only, and reflects the definitive electronic version of the article, found at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2972/hesperia.88.2.0365>. hesperia Jennifer Sacher, Editor Editorial Advisory Board Carla M. Antonaccio, Duke University Effie F. Athanassopoulos, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Angelos Chaniotis, Institute for Advanced Study Jack L. Davis, University of Cincinnati A. A. Donohue, Bryn Mawr College Jan Driessen, Université Catholique de Louvain Marian H. Feldman, University of California, Berkeley Gloria Ferrari Pinney, Harvard University Thomas W. Gallant, University of California, San Diego Sharon E. J. Gerstel, University of California, Los Angeles Guy M. Hedreen, Williams College Carol C. Mattusch, George Mason University Alexander Mazarakis Ainian, University of Thessaly at Volos Lisa C. Nevett, University of Michigan John H. Oakley, The College of William and Mary Josiah Ober, Stanford University John K. Papadopoulos, University of California, Los Angeles Jeremy B. Rutter, Dartmouth College Monika Trümper, Freie Universität Berlin Hesperia is published quarterly by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Founded in 1932 to publish the work of the American School, the jour- nal now welcomes submissions -

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

Creating a Character

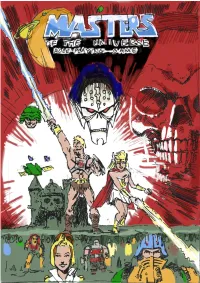

This game is based on Mattel's Masters of the Universe. It would be nothing without the many people involved in creating the brand and everything connected to it. I've tried to acknowledge everyone that I know had a part but there's bound to be omissions. Thanks to everyone involved. A brand as large as this is not easy to wrap one's head around and while there's only one writer of this game most of the information here was originally collected by fans and shared on various websites, mailing lists and forums. I owe a great gratitude to all those people and I've tried to credit everyone but there might be people I've neglected to mention. I'd be happy to correct any mistakes, and change online aliases to the correct names if you wish. This is version 0.4 MOTU RPG created by Daniel Schenström Masters of the Universe Classics (MOTUC) entries in this game mostly written by Scott Neitlich and Danielle Gelehrter. Masters of the Universe created and expanded by: Roger Sweet, Mark Taylor, Ted Mayer, Tony Guerro, Donald F. Glut, Alfredo Alcala, Colin Bailey, Michael Halperin, Bruce Timm, Tim Kilpin, Lou Scheimer, Dave Capper, Alan Tyler, Ed Watts, Mark Jones, James McElroy, Mike McKittrick, William George, Dave Maurer, Jim Keifer, Dave Wolfram, Stephen Lee, Scott Neitlich, Val Staples, Emiliano Santalucia, Josh Van Pelt, James Eatock, Robert Lamb, David Wise, Paul Dini, Larry DiTillio, J. Michael Stracszynski, Rowby Goren, Warren Greenwood, Gary Cohn, George Caragonne, Ron Wilson, Evelyn Stein, Thanks to: he-man.org, The Power and Honor Foundation, Mattel, Patrick Fogarty, the He-man wiki, Illustrations by: Daniel Schenström Two images are extensions and baed off of Filmation animation background plates. -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

Islamic Gunpowder Empires : Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals / Douglas E

“Douglas Streusand has contributed a masterful comparative analysis and an up-to- S date reinterpretation of the significance of the early modern Islamic empires. This T book makes profound scholarly insights readily accessible to undergraduate stu- R dents and will be useful in world history surveys as well as more advanced courses.” —Hope Benne, Salem State College E U “Streusand creatively reexamines the military and political history and structures of the SAN Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires. He breaks down the process of transformation and makes their divergent outcomes comprehensible, not only to an audience of special- ists, but also to undergraduates and general readers. Appropriate for courses in world, early modern, or Middle Eastern history as well as the political sociology of empires.” D —Linda T. Darling, University of Arizona “Streusand is to be commended for navigating these hearty and substantial historiogra- phies to pull together an analytical textbook which will be both informative and thought provoking for the undergraduate university audience.” GUNPOWDER EMPIRES —Colin Mitchell, Dalhousie University Islamic Gunpowder Empires provides an illuminating history of Islamic civilization in the early modern world through a comparative examination of Islam’s three greatest empires: the Otto- IS mans (centered in what is now Turkey), the Safavids (in modern Iran), and the Mughals (ruling the Indian subcontinent). Author Douglas Streusand explains the origins of the three empires; compares the ideological, institutional, military, and economic contributors to their success; and L analyzes the causes of their rise, expansion, and ultimate transformation and decline. Streusand depicts the three empires as a part of an integrated international system extending from the At- lantic to the Straits of Malacca, emphasizing both the connections and the conflicts within that AMIC system. -

Violence, Protection and Commerce

This file is to be used only for a purpose specified by Palgrave Macmillan, such as checking proofs, preparing an index, reviewing, endorsing or planning coursework/other institutional needs. You may store and print the file and share it with others helping you with the specified purpose, but under no circumstances may the file be distributed or otherwise made accessible to any other third parties without the express prior permission of Palgrave Macmillan. Please contact [email protected] if you have any queries regarding use of the file. Proof 1 2 3 3 4 Violence, Protection and 5 6 Commerce 7 8 Corsairing and ars piratica in the Early Modern 9 Mediterranean 10 11 Wolfgang Kaiser and Guillaume Calafat 12 13 14 15 Like other maritime spaces, and indeed even large oceans such as the 16 Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean was not at all a ‘no man’s sea’ – as 17 the sea in general appears, opposed to territorial conquest and occupa- 18 tion of land, in a prominent way in Carl Schmitt’s opposition between 19 a terrestrian and a ‘free maritime’ spatial order.1 Large oceanic spaces 20 such as the Indian Ocean and smaller ones such as the Mediterranean 21 were both culturally highly saturated and legally regulated spaces.2 22 The Inner Sea has even been considered as a matrix of the legal and 23 political scenario of imposition of the Roman ‘policy of the sea’ that 24 had efficiently guaranteed free circulation and trade by eliminating 25 the pirates – Cicero’s ‘enemy of mankind’ 3– who formerly had infected the 26 Mediterranean. -

The Quixotic Return of Heroism in GK Chesterton's Modernism

Columbia University Department of English & Comparative Literature Tilting After the Trenches: The Quixotic Return of Heroism in G.K. Chesterton’s Modernism Luke J. Foster | April 6, 2015 Prof. Erik Gray, Advisor The Senior Essay, presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors in English. Dedicated to Grace Catherine Greiner, a hope unlooked-for and a light undimmed. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, “Ulysses.” Foster 2 Heroic and Ironic Chivalry Today almost forgotten, G.K. Chesterton’s “Lepanto” achieved immense popularity during World War I as a heroic vindication of the British cause. Chesterton published “Lepanto” three years before the outbreak of war in the weekly he edited, The Eye-Witness. A 173-line poem in ballad form, “Lepanto” deals with the decisive naval battle of 1571 when a coalition fleet drawn from the Habsburg Empire and several Italian city-states defeated a superior Ottoman naval force in the Ionian Sea. But from the decisively stressed opening syllables (“White founts falling”1), “Lepanto” looks beyond the historical significance of the battle and seeks to establish a myth with much broader implications. Chesterton, as his biographer Ian Ker explains, claimed that the story of Lepanto demonstrated that “all wars were religious wars,” and he intended the poem as a comment on the meaning of warfare in general.2 After the outbreak of World War I, “Lepanto” was read as an encouragement to British troops in the field. -

The Apogee of the Hispano-Genoese Bond, 1576-1627

Hispania, LXV/1, num. 219 (2005) THE APOGEE OF THE HISPANO-GENOESE BOND, 1576-1627 por THOMAS KIRK New York University in Florence (Italy) RESUMEN: El periodo entre 1576 y 1627 se caracteriza por ser un momento de intensa coopera ción entre España y la república de Genova. Iniciado con una guerra civil en Genova simultánea a una suspensión de pagos en Madrid, concluye con el estallido de un con flicto bélico en el norte de Italia y con una nueva bancarrota. Los dramáticos aconteci mientos con los que se inicia nuestro periodo de estudio facilitaron la estabilidad inter na de la república y sirvieron para fortalecer los vínculos con España. El mecanismo de simbiosis —-dependencia española de la capacidad financiera de Genova y dependencia de la república de la protección de la Corona— no impidió momentos de tensión entre ambos aliados. Aun así, los fuertes intereses comunes, sin mencionar la superioridad militar española y el carácter asimétrico de la relación, explican que dichas tensiones se manifestaran en una dimensión simbólica. Sin embargo, es evidente que esta relación no podía durar siempre, por lo que en el momento culminante de la presencia del capital genovés en España y de dependencia de la protección militar de la corona, se produce una ruptura del equilibrio que madurará algunas décadas después. PALABRAS CLAVE: Genova. Monarquía Hispánica. Sistema financiero. Galeras. Revuelta de 1575. ABSTRACT: The half century between 1576 and 1627 witnessed the most intense relations between the Republic of Genoa and Spain. This period, clearly demarcated at both its beginning and ending points, was ushered in by a brief war in Genoa accompanied by royal insolvency in Spain, and brought to a close by fighting in northern Italy and another quiebra in Spain. -

Downloaded License

Journal of early modern history (2021) 1-36 brill.com/jemh Lepanto in the Americas: Global Storytelling and Mediterranean History Stefan Hanß | ORCID: 0000-0002-7597-6599 The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK [email protected] Abstract This paper reveals the voices, logics, and consequences of sixteenth-century American storytelling about the Battle of Lepanto; an approach that decenters our perspective on the history of that battle. Central and South American storytelling about Lepanto, I argue, should prompt a reconsideration of historians’ Mediterranean-centered sto- rytelling about Lepanto—the event—by studying the social dynamics of its event- making in light of early modern global connections. Studying the circulation of news, the symbolic power of festivities, indigenous responses to Lepanto, and the autobi- ographical storytelling of global protagonists participating at that battle, this paper reveals how storytelling about Lepanto burgeoned in the Spanish overseas territories. Keywords Battle of Lepanto – connected histories – production of history – global history – Mediterranean – Ottoman Empire – Spanish Empire – storytelling Connecting Lepanto On October 7, 1571, an allied Spanish, Papal, and Venetian fleet—supported by several smaller Catholic principalities and military entrepreneurs—achieved a major victory over the Ottoman navy in the Ionian Sea. Between four hundred and five hundred galleys and up to 140,000 people were involved in one of the largest naval battles in history, fighting each other on the west coast of Greece.1 1 Alessandro Barbero, Lepanto: la battaglia dei tre imperi, 3rd ed. (Rome, 2010), 623-634; Hugh Bicheno, Crescent and Cross: the Battle of Lepanto 1571 (London, 2003), 300-318; Peter Pierson, © Stefan Hanss, 2021 | doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10039 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license.