Adaptive State Capitalism in the Indian Coal Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AR-15-16 with Cover.Pmd

Annual Report 2015-16 (April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016) OF CHEM E IC T A U L T I E T N S G N I I N E N E A I R D S N I E STD. 1947 Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers 1 List of Council Members for 2015 & 2016 2015 Designation 2016 Mr G V Sethuraman, Director, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., C-2, Shantiniwas, Mettuguda, Mr Shyam Bang, Executive Director, Jubilant Life Sciences Ltd., 1A, Sector 16A, Noida Secunderabad – 500 017, Andhra Pradesh, [O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, President - 201 301, Uttar Pradesh, [R] (011) 2922-9999, [Mobile] (0)9810106660, [R] (040) 2733-4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] [email protected] Prof Ch V Ramachandra Murthy, Department of Chemical Engineering, Andhra Univer- Immediate Past Mr G V Sethuraman, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., Plot No. 138-A, IDA Mallapur, Hyderabad sity, Waltair, Visakhapatnam 530 003, [O] (0891) 2754871 Extn.496, [R] (0891) 2504520, President 500 076, Andhra Pradesh, O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, [R] (040) 2733- [Mobile] (0)94403 89136, [email protected] 4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] Mr D M Butala, 5, Mohak, B/h. Manisha Society, Behind Raja’s Lavkush, Bunglow, Near Prof S V Satyanarayana, Department of Chemical Engineering, JNTUA College of Upendra Bhatt’s Bunglow, Syed Vasana Road, Baroda 390 015, [R] (0265) 225-3977, Engineering, Anantapuramu Dist., Andhra Pradesh – 515002, [O] (08554) 272325 Ext: [Mobile] (0)9979853514, [email protected] Vice 4602, [Mobile] (0)9849509167, [email protected] Presidents Prof V V Basava Rao, Plot No; 184, Tirumala Nagar Colony, Meerpet (V), Moula-Ali Hous- Prof G A Shareef, 9, 2nd Stage, 2 Block, R M V Extn. -

Committee on Government Assurances (2009-2010)

COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT ASSURANCES (2009-2010) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) SEVENTH REPORT REQUESTS FOR DROPPING OF ASSURANCES Presented to Lok Sabha on 5 May, 2010 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI May, 2010 /Vaisakha, 1932 (Saka) CONTENTS PAGE Composition of the Committee (2009-2010) (iii) Introduction (iv) Report 1 - 3 Appendix-I Requests for dropping of Assurances (Not Acceded to) (i) Unstarred Question No. 3393 dated 30 July, 1992 regarding Funds to 4 - 5 Voluntary Organisations. (ii) Starred Question No. 597 dated 16 May, 1997 and Unstarred Question No. 2721 dated 23 July, 2009 regarding Amendments in Article 324 of 6 - 12 Constitution & Voting Percentage. Unstarred Question No. 4960 dated 26 April, 2000 regarding (iii) 13– 15 Recommendations of Fifth Pay Commission. (iv) Starred Question No. 6 dated 21 July, 2003 regarding Theft of Antiques. 16 - 19 (v) Unstarred Question No. 1325 dated 10 December, 2003 regarding Cash 20 - 21 Incentives to Poor Children. (vi) Unstarred Question Nos. 3312 dated 19 August, 2004 and 7007 dated 12 May, 2005 regarding Publication of Foreign News Paper & Publication of 22 - 27 International Herald Tribune. (vii) Unstarred Question No. 2899 dated 11 August, 2005 regarding Public- 28 - 29 Private Partnership in Defence Production. (viii) Unstarred Question No. 3949 dated 23 August, 2005 regarding 30 – 32 Recommendations of Past Committee. (ix) Unstarred Question No. 453 dated 25 November, 2005 regarding Law 33 – 35 Commission Report. (x) Starred Question No. 2 dated 17 February, 2006 regarding Sate Funding of Elections. 36 - 38 39 - 40 (xi) Unstarred Question No. 327 dated 26 July, 2006 regarding Revival of Ailing Hindustan Shipyard Corporation Limited. -

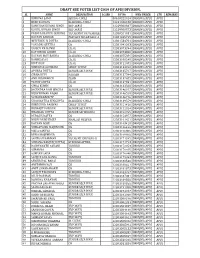

Application Employee of High Sr No

Application Employee of High Sr No. Seq No Rollno Applicant Full Name Father's Full Name Applicant Mother Name DOB (dd/MMM/yyyy) Domicile of State Category Sub_Category Email ID Gender Mobile Number Court Allahabad Is Present Score 1 1000125 2320015236 ANIL KUMAR SHIV CHARAN ARYA MAHADEVI 6/30/1990 Uttar Pradesh OBC Sports Person (S.P.)[email protected] Male 9911257770 No PRESENT 49 2 1000189 2320015700 VINEET AWASTHI RAM KISHOR AWASTHI URMILA AWASTHI 4/5/1983 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 8423230100 No PRESENT 43 3 1000190 2110045263HEMANT KUMAR SHARMA GHANSHYAM SHARMA SHAKUNTALA DEVI 3/22/1988 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] 9001934082 No PRESENT 39 4 1000250 2130015960 SONAM TIWARI SHIV KUMAR TIWARI GEETA TIWARI 4/21/1991 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] Male 8573921039 No PRESENT 44 5 1000487 2360015013 RAJNEESH KUMAR RAJVEER SINGH VEERWATI DEVI 9/9/1989 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9808520812 No PRESENT 41 6 1000488 2290015053 ASHU VERMA LATE JANARDAN LAL VERMA PADMAVATI VERMA 7/7/1992 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9005724155 No PRESENT 36 7 1000721 2420015498 AZAJUL AFZAL MOHAMMAD SHAHID NISHAD NAZMA BEGUM 2/25/1985 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 7275529796 No PRESENT 27 8 1000794 2250015148AMBIKA PRASAD MISHRA RAM NATH MISHRA NIRMALA DEVI 12/24/1991 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] Male 8130809970 No PRESENT 36 9 1001008 2320015652 SATYAM SHUKLA PREM PRAKASH -

Who's Who – India As on 29.04.2010

Who's Who – India as on 29.04.2010 President of India Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil Vice President of India Shri Mohd. Hamid Ansari Prime Minister of India Dr. Manmohan Singh Cabinet Ministers Serial Portfolio Name of Minister Number Prime Minister and also In‐Charge of the Ministries/Departments viz: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions; 1. Ministry of Planning; Dr. Manmohan Singh Ministry of Water Resources; Department of Atomic Energy; and Department of Space 2. Minister of Finance Shri Pranab Mukherjee Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food 3. Shri Sharad Pawar & Public Distribution 4. Minister of Defence Shri A.K. Antony 5. Minister of Home Affairs Shri P. Chidambaram 6. Minister of Railways Km. Mamata Banerjee 7. Minister of External Affairs Shri S.M. Krishna 8. Minister of Steel Shri Virbhadra Singh Shri Vilasrao 9. Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises Deshmukh 10. Minister of Health and Family Welfare Shri Ghulam Nabi Azad Shri Sushil Kumar 11. Minister of Power Shinde Shri M. Veerappa 12. Minister of Law and Justice Moily 13. Minister of New and Renewable Energy Dr. Farooq Abdullah 14. Minister of Urban Development Shri S. Jaipal Reddy 15. Minister of Road Transport and Highways Shri Kamal Nath 16. Minister of Overseas Indian Affairs Shri Vayalar Ravi 17. Minister of Textiles Shri Dayanidhi Maran 18. Minister of Communications and Information Technology Shri A. Raja 19. Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas Shri Murli Deora 20. Minister of Information and Broadcasting Smt. Ambika Soni Shri Mallikarjun 21. Minister of Labour and Employment Kharge 22. -

Reforming Soes in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India

ADBI Working Paper Series REFORMING SOES IN ASIA: LESSONS FROM COMPETITION LAW AND POLICY IN INDIA Vijay Kumar Singh No. 1056 December 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute Vijay Kumar Singh is a professor and head of the Department of Law and Management at the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies School of Law in Dehradun, India. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Singh, V. K. 2019. Reforming SOEs in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India. ADBI Working Paper 1056. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/reforming-soes-asia-lessons-competition-law-policy-india Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 1056 V. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

(2016-2017) (Sixteenth Lok Sabha) Ministry of Minority Affairs

39 STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF MINORITY AFFAIRS DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-2018) THIRTY-NINTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) i THIRTY-NINTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF MINORITY AFFAIRS DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-2018) Presented to Lok Sabha on 17.03.2017 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 17.03.2017 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) ii CONTENTS PAGE(s) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2016-17) (iv) INTRODUCTION (vi) REPORT CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTORY 1 CHAPTER - II GENERAL PERFORMANCE OF MINISTRY 4 CHAPTER - III FREE COACHING AND ALLIED SCHEME 26 CHAPTER - IV RESEARCH STUDIES MONITORING & 33 EVALUATION OF DEVELOPMENT SCHEME FOR MINORITIES CHAPTER - V SKILL DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE 36 (SEEKHO AUR KAMAO SCHEME) CHAPTER - VI HAJ DIVISION 50 ANNEXURES I. MINUTES OF THE ELEVENTH SITTING OF 82 THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-17) HELD ON TUESDAY, 28th FEBRUARY, 2017. II. MINUTES OF THE TWELFTH SITTING OF THE 85 STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-17) HELD ON THURSDAY, 16th MARCH, 2017. APPENDIX STATEMENT OF OBSERVATIONS/ 87 RECOMMENDATIONS iii COMPOSITION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (2016-2017) SHRI RAMESH BAIS - CHAIRPERSON MEMBERS LOK SABHA 2. Shri Kantilal Bhuria 3. Shri Santokh Singh Chaudhary 4. Shri Sher Singh Ghubaya 5. Shri Jhina Hikaka 6. Shri Sadashiv Kisan Lokhande 7. Smt. K. Maragatham 8. Shri Kariya Munda 9. Prof. Seetaram Azmeera Naik 10. Shri Asaduddin Owaisi 11. -

1. Cause List of Cases Filed Between 01.01.2018 to 21.03.2020 Shall Not Be Published Till Further Orders

05.04.2021 IN PARTIAL MODIFICATION RELATING TO THE SITTING ARRANGEMENT OF THE HON'BLE JUDGES w.e.f. 05.04.2021, THE COURT NUMBERS ALREADY SHOWN IN THE ADVANCE CAUSE LIST FOR 5th & 6th APRIL FOR THE FOLLOWING HON'BLE JUDGES SHALL NOW BE READ AS UNDER: JUDGES NAME COURT NO. 1. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJEEV SACHDEVA 7 2. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE VIBHU BAKHRU 43 3. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE V. KAMESWAR RAO 14 4. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PRATEEK JALAN 16 “All the Advocates/Litigants are informed that in view of the directions dated 09.03.2021 passed by Hon. DB-II in W.P.(C) 2018/2021 and W.P.(C) 2673/2021 half of the cases (starting from the Supplementary List/s) listed for a particular day shall be taken up in the Pre-lunch Session and rest of the cases shall be taken up in the Post-lunch Session. All the Advocates/Litigants may accordingly reach the Court Rooms according to the turn of their case/s in order to curtail the number of people in court premises at the same time.” NOTE 1. CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020 SHALL NOT BE PUBLISHED TILL FURTHER ORDERS. HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No. 384/RG/DHC/2020 DATED: 19.3.2021 OFFICE ORDER HON'BLE ADMINISTRATIVE AND GENERAL SUPERVISION COMMITTEE IN ITS MEETING HELD ON 19.03.2021 HAS BEEN PLEASED TO RESOLVE THAT HENCEFORTH THIS COURT SHALL PERMIT HYBRID/VIDEO CONFERENCE HEARING WHERE A REQUEST TO THIS EFFECT IS MADE BY ANY OF THE PARTIES AND/OR THEIR COUNSEL. -

THURSDAY, the 14TH MARCH, 2002 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A.M.) 11-00 A.M

THURSDAY, THE 14TH MARCH, 2002 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No. 161 regarding Territorial demarcation between India and Bangladesh. Starred Question No. 162 regarding Export of Basmati rice. Starred Question No. 164 regarding Procurement of paddy at MSP. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos. 163, 165 to 180 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos.1164 to 1318 were laid on the Table. 12 Noon 3. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Pramod Mahajan (Minister of Parliamentary Affairs, Minister of Communications and Information Technology) laid on the Table the following papers:— I. A copy (in English and Hindi) of the Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (Department of Information Technology) Notification G.S.R. No. 892 (E) dated 11th December, 2001 publishing the Semiconductor Integrated Circuits Layout Design Rules, 2001, under sub-section (2)(i) of Section 96 of the Semiconductor Circuits Layout Design Act, 2000, II. A copy (in English and Hindi) of the Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (Department of Information Technology) Notification G.S.R. No. 512 (E) dated 9th July, 2001 publishing the Information Technology (Certifying Authority) Regulations, 2001, under sub-section (3) of Section 89 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Shri Kariya Munda (Minister of Agro and Rural Industries) laid on the Table the following papers:- 14TH MARCH, 2002 (1) A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub- section (1) of section 19 of the Coir Industries Act, 1953:— (a) Forty-seventh Annual Report of the Coir Board, Kochi, for the year 2000- 2001, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. -

Apdj Voter List Gm-P-Mlg

DRAFT SBE VOTER LIST-2019 OF APDJ DIVISION. SL NAME DESIGNATION I.CARD P.F NO WKG UNDER STN REMARKS 1 SUPRINA LAMA JE(DRG-CIVIL) 00610322024 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 2 DESH RAJ DAS Sr.SE(DRG-CIVIL) 12221506188 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 3 KANCHAN KUMAR SINGH JE(P.WAY) 12229800867 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 4 RAHUL KUMAR SINGH JE(P.WAY) 12229800873 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 5 PREM BAHADUR GURUNG TECH.(MOTOR VEHICLE 12300551031 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 6 KALYAN SARKAR PRIVATE SECRETARY-II 12301425729 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 7 NITYENDU N DUTTA Sr.SE(DRG-CIVIL) 12301534701 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 8 YANADRI GEETHA OS 12301941203 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 9 SANJOY KR NANDI Ch. OS 12303073294 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 10 RATHIN KR GHOSH Ch. OS 12303073300 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 11 KALYAN MOY BARUA Sr.SE(DRG-CIVIL) 12303075886 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 12 KANIKA DAS Ch. OS 12303100248 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 13 DIPTI ROY Ch. OS 12303122682 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 14 SUKUMAR GOSWAMI CHIEF TYPIST 12303134052 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 15 APURBA DUTTA SENIOR SE(P.WAY) 12303135767 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 16 GIRIJA DEVI FARASH 12303137594 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 17 ANIL BHOWMICK PEON 12303137685 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 18 TRIDIP GUPTA Ch. OS 12303137831 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 19 SIPRA KUNDU OS 12303143508 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 20 JOGENDRA RAM SINGHA SENIOR SE(P.WAY) 12303146017 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 21 BIJOY KUMAR RAJAK SENIOR SE(P.WAY) 12303146558 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 22 S CHAKRABORTY OS 12303146716 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 23 SIDDHARTHA SENGUPTA Sr.SE(DRG-CIVIL) 12303149559 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 24 SURESH KR PASWAN CHIEF TYPIST 12303151426 DRM(W)/APDJ APDJ 25 BISWAJIT PODDER SENIOR SE(P.WAY) 12303152054 DRM(W)/APDJ -

MINISTRY of COAL and MINES DEMAND NO. 10 Department of Coal

Notes on Demands for Grants, 2004-2005 25 MINISTRY OF COAL AND MINES DEMAND NO. 10 Department of Coal A. The Budget allocations, net of recoveries, are given below: (In crores of Rupees) Budget 2003-2004 Revised 2003-2004 Budget 2004-2005 Major Head Plan Non-Plan Total Plan Non-Plan Total Plan Non-Plan Total Revenue 285.90 152.00 437.90 150.00 151.66 301.66 119.82 200.00 319.82 Capital ... ... ... ... ... ... 103.50 ... 103.50 Total 285.90 152.00 437.90 150.00 151.66 301.66 223.32 200.00 423.32 1. Secretariat-Economic Services 3451 ... 6.28 6.28 ... 6.01 6.01 4.50 6.77 11.27 Labour and Employment Coal Mines Labour Welfare 2. Contribution to the Coal Mines Pension Scheme/Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme 2230 ... 28.23 28.23 ... 28.23 28.23 ... 31.46 31.46 Coal and Lignite 3. Conservation and Safety in Coal Mines (Met out of cess collections) 2803 ... 64.00 64.00 ... 64.00 64.00 ... 90.00 90.00 4. Development of Transportation infrastructure in Coal field areas (Met out of cess collections) 2803 ... 50.94 50.94 ... 50.94 50.94 ... 69.12 69.12 5. Scheme of grant-in-aid to PSUs for implementation of VRS 2803 138.44 ... 138.44 ... ... ... ... ... ... 6. Loan to PSUs for implementation of VRS 6803 ... ... ... ... ... ... 103.50 ... 103.50 7. Research & Development Programme 2803 22.48 ... 22.48 10.04 ... 10.04 9.88 ... 9.88 8. Regional Exploration 2803 56.10 ... 56.10 85.18 .. -

List of Council of Ministers

LIST OF COUNCIL OF MINISTERS Shri Narendra Modi Prime Minister and also in-charge of: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Atomic Energy; Department of Space; and All important policy issues; and All other portfolios not allocated to any Minister. CABINET MINISTERS 1. Shri Raj Nath Singh Minister of Home Affairs. 2. Smt. Sushma Swaraj Minister of External Affairs. 3. Shri Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance; and Minister of Corporate Affairs. 4. Shri Nitin Jairam Gadkari Minister of Road Transport and Highways; Minister of Shipping; and Minister of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. 5. Shri Suresh Prabhu Minister of Commerce and Industry. 6. Shri D.V. Sadananda Gowda Minister of Statistics and Programme Implementation. 7. Sushri Uma Bharati Minister of Drinking Water and Sanitation. 8. Shri Ramvilas Paswan Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. 9. Smt. Maneka Sanjay Gandhi Minister of Women and Child Development. 10. Shri Ananthkumar Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers; and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. 11. Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad Minister of Law and Justice; and Minister of Electronics and Information Technology. Page 1 of 7 12. Shri Jagat Prakash Nadda Minister of Health and Family Welfare. 13. Shri Ashok Gajapathi Raju Minister of Civil Aviation. Pusapati 14. Shri Anant Geete Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises. 15. Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal Minister of Food Processing Industries. 16. Shri Narendra Singh Tomar Minister of Rural Development; Minister of Panchayati Raj; and Minister of Mines. 17. Shri Chaudhary Birender Minister of Steel. Singh 18. Shri Jual Oram Minister of Tribal Affairs.