10. Authorisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern and Western Queensland Region

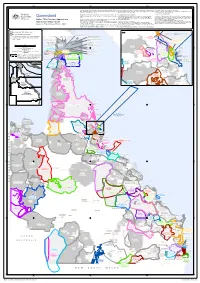

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

First Nations Connections Plan

First Nations Connections Plan Incorporating our Innovate Reconciliation Action Plan Ener January 2020-23 Queensland First Nations Connections Plan January 2020-23 ••• •• ABOVE: Alan Palmer (left) and Sam Bush (right) from Yurika, along with from Jay Shelley - 5B Solar (center) at the completion of the Doomagee Solar Farm project • •• in September, 2019. ••• • BELOW: Energy Queensland was recognised at the 2018 Queensland Reconciliation Awards, winning Acknowledgement the Partnership Category, with Queensland Theatre/ Energy Queensland would like to acknowledge Lonestar Company for the production ‘My Name is Jimi’. and pay respect to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestors across Queensland where we work and travelled to develop this Reconciliation Action Plan. The foundations laid by these ancestors – our First Nations peoples – gives strength, inspiration and courage to current and future generations, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, towards creating a better Queensland. • We would especially like to acknowledge • • --,·§·~~~ the Traditional Owners and Custodians who honoured us by spending time sharing their • knowledge and wisdom. Their participation • in this process ensures that our Plan will be a • mechanism to ensure meaningful relationships are built between our businesses and the First Nations communities throughout Queensland. 2 First Nations Connections Plan January 2020-23 • • Contents A message from our Chairman and Chief Transformation Officer 4 A message -

The Yarning Up! Project Report 2013-2014

THE YARNING UP! PROJECT REPORT 2013-2014 Barbara Blair James Chapman Bruce Little Lavina Little Kathy Prentice Georgina Tanner Coral Walker Artwork 1 e feelings, thoughts, words and opinions expressed in this report are those of the Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and South Sea Islander peoples of the Bundaberg area. Artwork by James Chapman Artwork 2 Artwork 1 Title: e Teaching Description: is artwork explains how an ancestral gure hovers over an initiation ceremony where teenage Aboriginal males are led into circular rocks formation (bora ring). is is an example of how ancestors pass down knowledge to elders, who provide the teaching to the younger generation. Artwork 2 Title: e Separation Description: Explains the period of the “Stolen Generation” where the half caste Aboriginal children were taken away from their home land, culture and families. On the le hand side of the painting it represents the full blood “dark skinned” children and on the right hand side of Artwork 3 the painting is the half caste “fair skinned” children. is is one of the most damaging events that took place in our Aboriginal history that was put in place by the government. Artwork 3 Title: Our Healing Description: Us mob creating a solution to take a cultural approach to work together within the community as one, towards a healing in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and families with minimal mainstream involvement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Traditional Acknowledgement ..............................................................................................................4 -

2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022

DRAFT V20 2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022 Working to recover, rebuild and reconnect more resilient Queensland communities following the 2019 Queensland Bushfires August 2020 to come Document details Interpreter Security classification Public The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have Date of review of security classification August 2020 difficulty in understanding this report, you can access the Translating and Interpreting Authority Queensland Reconstruction Authority Services via www.qld.gov.au/languages or by phoning 13 14 50. Document status Final Disclaimer Version 1.0 While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no QRA reference QRATF/20/4207 responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. ISSN 978-0-9873118-4-9 To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Copyright Copies This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. © The State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority), August 2020. Copies of this publication are available on our website at: https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/fitzroy Further copies are available upon request to: Licence Queensland Reconstruction Authority This work is licensed by State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority) under a Creative PO Box 15428 Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International licence. City East QLD 4002 To view a copy of this licence, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Phone (07) 3008 7200 In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this annual report, as long as you attribute [email protected] the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority). -

Authorisation and Decision-Making in Native Title

Authorisation and decision-making in native title Nick Duff Goldfields Land and Sea Council Authorisation and decision-making in native title Authorisation and decision-making in native title Nick Duff Goldfields Land and Sea Council First published in 2017 by AIATSIS Research Publications © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2017. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this publication, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4285 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Duff, Nick, author. Title: Authorisation and decision-making in native title / Nick Duff. -

Statement of Eminent Australians on the Continuing Damage

Statement of Eminent Australians on the continuing damage caused by the discrimination, racism and lack of justice towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, exemplified by the continuation of the Northern Territory Intervention Whi le the Australian nation deliberates on the future of its relationship with the First ations of this land, most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples arc focussed on the continuing discrimination, racism and lack of justice, shown towards them by Federal, State and Territo') Governments in so many areas. An obvious example is the failure often years of Federal Government INTERVENTION in the Northern Territory where 73 remote Aboriginal communities (and hundreds more in homelands in hinterlands) remain subjected to discriminatory legislation that no other Australian citizen endures in its crushing totality. The signatories to this statement suppo1t the recent demands by orthem Territory Elders for an immediate repeal of the Intervention measures, some of which were strengthened and extended for ten years in 2012, by the misleadingly renamed 'Stronger Futures' legislation. We support the calls by Elders in their June 29th 2017 statement for an end to government control of community livi ng areas and the return of community control of housing, employment and local governance. We also support their insistence on an apology and their right to determine their futures and distinctive pathways. 1 First ations' voices have been increasingly ignored since the abolition of ATS IC in 2004 and the Intervention in 2007 and conditions have deteriorated. It is time that Federal and Territory politicians acknowledged the independent assessments2 that the Intervention measures continue to fai l3 and the necessity of establishing genuine self-determination and community control. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

James Fredric Weiner: a Bibliography

JAMES FREDRIC WEINER: A BIBLIOGRAPHY 2 INTRODUCTION In 2017, James Fredric Weiner decided that he didn’t want to be Jimmy any more, so the next year he turned into Jaimie Pearl Bloom. Or maybe it was Jaimie who decided to dispose of Jimmy. This bibliography lists Jimmy’s publication and reports written between the time he arrived in Canberra in 1979 and the time when he made his choice to start a new life in 2017. Jimmy spent seven years, from 1979 to 1985, as a PhD student and post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Anthropology in what was then the Research School of Pacific Studies at the Australian National University (ANU). He was awarded his doctorate in 1984. The focus of his research was the lifeworld of the Foi (or Foe) people who live in the Southern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea (PNG). His doctoral thesis, The Heart of the Pearl Shell, was published in 1988. By the time of its publication, Jimmy was ensconced in the ‘other’ anthropology department at the ANU – the one then known as the Department of Prehistory (later Archaeology) and Anthropology, which belonged to the so-called ‘Faculties’, where undergraduates were taught. Jimmy spent four years, from 1986 to 1989, lecturing in that department. Then, between 1990 to 1994, Jimmy spent another four years lecturing in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Manchester. Jimmy came back to Australia towards the end of 1994 to take up a position as Professor and Head of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Adelaide. -

APPLICATIONS National the National Native Title Tribunal Now Posts Summaries of Registration Test Decisions on Their Website At

APPLICATIONS National The National Native Title Tribunal now posts summaries of registration test decisions on their website at: http://www.nntt.gov.au The following decisions are listed for September and October: People of Naghir #1 pass Tjupan sff Rubibi #10 sff Rubibi (combined application) pass Warrwa People sff Gunggandji pass North West Nations sff Wadja People sff M.Dawson, F.Wally & Pine Hill Station pass L.Whibby sff Wirri Clan pass Rosie Mulligan & Ors sff Nyigina and Mangala Rubibi Claim #12 sff (combined application) pass Rubibi #9 sff Spinifex People pass Bidjara People #4 pass Gooniyandi (combined Wulgurukaba People #1 pass application) pass Wulgurukaba People #2 pass Bunjalung People sff Bardi/Jawi pass Dharawal People pass Kudjala & Jirandali People pass Djabera-Djabera People pass Butchulla People pass Ngarrawanji pass Gurang People Darug # 3 dnp (amended 13/9/99) dnp Ngunawal (ACT) sff Harris Family pass Ngunnawal (ACT) sff Undumbi People dnp Indjilandji/Dithannoi People pass Warburton - Mantamaru pass Central East Goldfields Gooreng Gooreng People dnp (combined application) pass Indjilandji pass Central West Goldfields Waanyi Peoples pass (combined application) pass Lamboo (combined application) pass Ngarrindjeri #1 dnp Moorawarri Aboriginal People Yankunytjatjara/Antakirinja pass (amended 17/9/99) pass Eringa pass Ngawarr pass Karajarri #2 pass Swan Valley Nyungah Purnululu pass Community sff Gumilaroi sff Dja Dja Wurrung People Willi Willi (Dodd) sff (combined application) pass Wulli Wulli People sff Gomilaroi #3 sff Dieri Mitha dnp Widi Marra sff Wangkangurru/Yarluyandi Widi Marra sff People pass Bodney dnp Gobawarrah Minduarra Leregon #2 sff Yinhawanga (amended Mr Corrie Bodney (Snr) dnp 29/10/99) pass Sir Samuel Number 2 sff Walbunja pass Sff - Short form failure - means that the application was tested against a limited number of conditions. -

Native Title Information Handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Native Title Information Handbook Queensland 2016 © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies AIATSIS acknowledges the funding support of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Native Title Research Unit (NTRU) acknowledges the generous contributions of peer reviewers and welcomes suggestions and comments about the content of the Native Title Information Handbook (the Handbook). The Handbook seeks to collate publicly available information about native title and related matters. The Handbook is intended as an introductory guide only and is not intended to be, nor should it be, relied upon as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If you are aware that this publication contains any errors or omissions please contact us. Views expressed in the Handbook are not necessarily those of AIATSIS. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 02 6261 4223 Fax 02 6249 7714 Email [email protected] Web www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Native title information handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN: 9781922102539 (ebook) Subjects: Native title (Australia)--Queensland--Handbooks, manuals, etc. Aboriginal Australians--Land tenure--Queensland. Land use--Law and legislation--Queensland. Aboriginal Australians--Queensland. Other Creators/Contributors: Australian Institute of Aboriginal -

MS 5070 the Indigenousx Collection 2013-2016

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5070 The IndigenousX Collection 2013-2016 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………………… page 2 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………… page 2 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………………….. page 3 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………… page 4 ADMINISTRATIVE NOTE……………………………………….. page 4 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………….. page 5 BOX LIST …………………………………………………………. page 12 MS 5070 The IndigenousX Collection COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Sarah Kennedy Title: The IndigenousX Collection Collection no: MS 5070 Date range: 2013-2016 Extent: 17cm (1 archive box) Repository: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT It is a condition of use of this finding aid, and of the collection described in it, that users ensure that any use of the information contained in it is sympathetic to the views and sensitivities of relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This includes: Language Users are warned that this finding aid may contain words and descriptions which may be culturally sensitive and which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Terms and descriptions which reflect the author’s attitude, or that of the period in which the manuscript was written, and which may be considered inappropriate today in some circumstances, may also be used. Deceased persons Users of this finding aid should be aware that, in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, seeing images of deceased persons in photographs, film and books or hearing them in recordings etc. may cause sadness or distress and in some cases, offend against strongly held cultural prohibitions. Back to top 2 MS 5070 The IndigenousX Collection ACCESS TO COLLECTION Access and use conditions Materials listed in this finding aid may be subject to access conditions required by Indigenous communities and/or depositors. -

AIATSIS Lan Ngua Ge T Hesaurus

AIATSIS Language Thesauurus November 2017 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Language Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://aiatsis.gov.au/atsilirn/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task.