An Investigation of the Help-Seeking Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: Evolution of a Dynamic Fracture System

n Gomez-Rivas, E., Bons, P.D., Koehn, D., Urai, J.L., Arndt, M., Virgo, S., Laurich, B., Zeeb, C., Stark, L., and Blum, P. (2014) The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: evolution of a dynamic fracture system. American Journal of Science, 314 (7). pp. 1104-1139. ISSN 0002- 9599 Copyright © 2014 American Journal of Science A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/94553/ Deposited on: 12 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 The Jabal Akhdar Dome in the Oman Mountains: evolution of a 2 dynamic fracture system 3 4 E. GOMEZ-RIVAS*, P. D. BONS*, D. KOEHN**, J. L. URAI***, M. ARNDT***, S. 5 VIRGO***, B. LAURICH***, C. ZEEB****, L. STARK* and P. BLUM**** 6 7 * Department of Geosciences, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Germany; enrique.gomez-rivas@uni- 8 tuebingen.de 9 ** School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom 10 *** Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geomechanics, RWTH Aachen University, Germany 11 **** Institute for Applied Geosciences (AGW), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany 12 13 ABSTRACT. The Mesozoic succession of the Jabal Akhdar dome in the Oman Mountains 14 hosts complex networks of fractures and veins in carbonates, which are a clear example of 15 dynamic fracture opening and sealing in a highly overpressured system. -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

Persian Gulf States, Old and New Co-Exist in Innovative and Intriguing Ways

PERsiAn OMAN, ABU DHABI, GulF QATAR AND DUBAI Aboard the Crystal Esprit CRUISE January 2–12, 2020 DUBAI FEATURING Trevor Marchand Emeritus Professor of Social Anthropology at SOAS, London DEAR TRAVELER, You are invited to join Archaeological Institute of America lecturer and host Trevor Marchand for this compelling cruise aboard the yacht-like, all-suite, 31-cabin Crystal Esprit. In the Persian Gulf states, old and new co-exist in innovative and intriguing ways. During this exploration of Dubai, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Oman you will visit the mosques, souks, educational institutions, and museums that reflect a fascinating juxtaposition of past and present that is unique to the Islamic world. Begin your exploration among the dazzling skyscrapers of Dubai, the business and cultural hub of the Middle East and home to some of the most stunning architectural masterpieces of the 20th and 21st centuries. Continue to Qatar, where visits to the old souq and the new Education City illustrate how dramatically change has come to the Gulf States. In the emirate of Abu Dhabi, museums, mosques, and Masdar City amaze with both their sheer grandeur and minute detail. Wrap up your journey with a cruise through the fjord-like waterways of Oman’s Musandam Peninsula and visits to some of the country’s culturally rich museums, mosques, and markets. For those who wish to further explore the region, optional pre- and post-cruise extensions in Dubai and Oman’s interior are also available. You will learn about the cultures, art, architecture, and history of this region on daily shore excursions and during an enriching onboard educational program with AIA lecturer Trevor Marchand and other onboard lecturers. -

The Two Yemens

1390_A24-A34 11/4/08 5:14 PM Page 543 330-383/B428-S/40005 The Two Yemens 171. Telegram From the Department of State to the Embassy in the People’s Republic of Southern Yemen1 Washington, February 27, 1969, 1710Z. 30762. Subj: US–PRSY Relations. 1. PRSY UN Perm Rep Nu’man,2 who currently in Washington as PRSYG observer at INTELSAT Conference, had frank but cordial talk with ARP Country Director Brewer February 26. 2. In analyzing causes existing coolness in USG–PRSYG relations, Ambassador Nu’man claimed USG failure offer substantial aid at time of independence and subsequent seizure of American arms with clasped hands insignia3 in possession of anti-PRSYG dissidents had led Aden to “natural” conclusion that USG distrusts PRSYG. He specu- lated this due to close US relationship with Saudis whom Nu’man al- leged, somewhat vaguely, had privately conveyed threats to overthrow NLF regime, claiming USG support. Nu’man asserted PRSYG desired good relations with USG and hoped USG would reciprocate. 3. Recalling history of USG attempts to develop good relations with PRSYG, Brewer underlined our feeling it was PRSYG which had not re- ciprocated. He reviewed our position re non-interference PRSY internal affairs, regretting publicity anti-USG charges (e.g. re arms) without first seeking our explanation. Brewer noted USG seeks maintain friendly relations with Saudi Arabia as well as PRSYG but we not responsible for foreign policy of either. 4. Nu’man reiterated SAG responsible poor state Saudi-PRSY con- tacts. Brewer demurred, noting SAG had good reasons be concerned over hostile attitude PRSYG leaders. -

UAE ROCK CLIMBING Five Years Later - an Update

UAE ROCK CLIMBING five years later - an update 1 UAE Rock Climbing - 2015 update INTRODUCTION pages 6 - 17 Information and Updates The web forum at uaeclimbing.com is no longer in active use. Various Facebook groups exist. Of these, "Real UAE Rock Climbers" is the most credible. It is a closed group - apply to join. Accidents The advice given in the guidebook on accident procedure is still broadly correct. Regrettably the UAE has still not implemented a national rescue service. Abu Dhabi emirate has helicopters with paramedics available but these would not necessarily be available in other emirates. One observation from a serious incident in Oman in 2010 is that it may be hard to direct local police to an accident location. Carrying GPS equipment and knowing how to communicate GPS coordinates would be helpful in those situations. Visiting climbers should of course make sure they have medical insurance. Climbing Walls Two major resources have appeared since the guidebook: Rock Republic in Dubai and the wall at Sorbonne University in Abu Dhabi. The latter has a private registration process. Instruction Courses The advice given in the guidebook on instruction is out of date. Ask for the latest situation at "Real UAE Rock Climbers". 2 UAE Rock Climbing - 2015 update KHASAB pages 23 - 27 Access situation: No substantial change Route development since the guidebook: Nothing new at Khasab Beach. A very strong North Face sponsored team (Alex Honnold, Hazel Findlay, others) toured the Musandam peninsula in a catamaran, recording some mountain routes on Jebel Letub near Sibi village and elsewhere. Also one multi-pitch seacliff route and some DWSing. -

Draft Provisonal Agenda and Time-Table

IT/GB-5/13/Inf. 2 June 2013 FIFTH SESSION OF THE GOVERNING BODY Muscat, Oman, 24-28 September 2013 NOTE FOR PARTICIPANTS Last Update: 15 July 2013 1. MEETING ARRANGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 DATE AND PLACE OF THE MEETING ........................................................................................................... 2 COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE SECRETARIAT ........................................................................................... 2 INVITATION LETTERS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ADMISSION OF PARTICIPANTS .................................................................................................................... 2 States that are Contracting Parties ......................................................................................................... 2 States that are not Contracting Parties................................................................................................... 3 Other international bodies or agencies .................................................................................................. 3 2. REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................................. 3 ONLINE PRE-REGISTRATION ..................................................................................................................... -

Late-Stage Tectonic Evolution of the Al-Hajar Mountains

Geological Magazine Late-stage tectonic evolution of the www.cambridge.org/geo Al-Hajar Mountains, Oman: new constraints from Palaeogene sedimentary units and low-temperature thermochronometry Original Article 1,2 3 4 3 4 5 Cite this article: Corradetti A, Spina V, A Corradetti , V Spina , S Tavani , JC Ringenbach , M Sabbatino , P Razin , Tavani S, Ringenbach JC, Sabbatino M, Razin P, O Laurent6, S Brichau7 and S Mazzoli1 Laurent O, Brichau S, and Mazzoli S (2020) Late-stage tectonic evolution of the Al-Hajar 1 Mountains, Oman: new constraints from School of Science and Technology, Geology Division, University of Camerino. Via Gentile III da Varano, 62032 2 Palaeogene sedimentary units and low- Camerino (MC), Italy; Department of Petroleum Engineering, Texas A&M University at Qatar, Doha, Qatar; temperature thermochronometry. Geological 3Total E&P, CSTJF, Avenue Larribau, 64000 Pau, France; 4DiSTAR, Università di Napoli Federico II, 21 Via vicinale Magazine 157: 1031–1044. https://doi.org/ cupa Cintia, 80126 Napoli, Italy; 5ENSEGID, Institut Polytechnique de Bordeaux, 1 allée Daguin, 33607 Pessac, 10.1017/S0016756819001250 France; 6Total E&P, Paris, France and 7Géosciences Environnement Toulouse (GET), Université de Toulouse, UPS, CNRS, IRD, CNES, 14 avenue E. Belin, 31400, Toulouse, France Received: 8 July 2019 Revised: 5 September 2019 Accepted: 15 September 2019 Abstract First published online: 12 December 2019 Mountain building in the Al-Hajar Mountains (NE Oman) occurred during two major short- – Keywords: ening stages, related to the convergence between Africa Arabia and Eurasia, separated by nearly Oman FTB; Cenozoic deformation; remote 30 Ma of tectonic quiescence. Most of the shortening was accommodated during the Late sensing; thermochronology Cretaceous, when northward subduction of the Neo-Tethys Ocean was followed by the ophio- lites obduction on top of the former Mesozoic margin. -

Geological Passport

Geological Passport www.moei.gov.ae Contact Details Ministry of Energy & Industry Geology & Mineral Resources Department PO Box 59 - Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates Phone +971 2 6190000 Toll Free 8006634 Fax +971 2 6190001 Email: [email protected] Website: www.moei.gov.ae © Ministry of Energy & Industry, UAE Geological Setting of the UAE e United Arab Emirates (UAE) are located on the southern side of the Arabian Gulf, at the north-eastern edge of the Arabian Plate. Although large areas of the country are covered in Quaternary sediments. e bedrock geology is well exposed in the Hajar Mountains and the Musandam Peninsula of the eastern UAE, and along the southern side of the Arabian Gulf west of Abu Dhabi. e geology of the Emirates can be divided into ten main components: (1) e Late Cretaceous UAE-Oman ophiolite; (2) A Middle Permian to Upper Cretaceous carbonate platform sequence, exposed in the northern UAE (the Hajar Supergroup); (3) A deformed sequence of thin limestone’s and associated deepwater sediments, with volcanic rocks and mélanges, which occurs in the Dibba and Hatta Zones; Geological map of the UAE (Scale 1:500 000) 1 (4) A ploydeformed sequence of metamorphic rocks, seen in the Masafi – Ismah and Bani Hamid areas; (5) A younger, Late Cretaceous to Palaeogene cover sequence exposed in a foreland basin along the western edge of the Hajar Mountains; (6) An extensive suite of Quaternary fluvial gravels and coalesced alluvial fans extending out from the Hajar Mountains; (7) A sequence of Late Miocene sedimentary rocks exposed in the western Emirates; (8) A number of salt domes forming islands in the Arabian Gulf, characterised by complex dissolution breccias with a varied clast suite of mainly Neoproterozoic (Ediacaran) sedimentary and volcanic rocks; (9) A suite of Holocene marine and near-shore carbonate and evaporate deposits along the southern side of the Arabian Gulf forming the classic Abu Dhabi sabkhas and Extensive Quaternary to recent aeolian sand dunes which underlie the bulk of Abu Dhabi Emirate. -

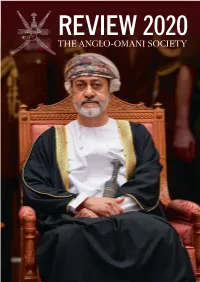

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development

Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Al-Hashmi, Julanda S. H. 2019. Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development.. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004191 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rifts in Omani Employment Culture: Emerging Joblessness in the Context of Uneven Development. A Julanda S. H. Al-Hashmi A Thesis in the Field of Government for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 Copyright ! Julanda Al-Hashmi 2019 Abstract Beginning in 1970, Oman experienced modernization at a rapid pace due to the discovery of oil. At that time, the country still had not invested much in infrastructure development, and a large part of the national population had low levels of literacy as they lacked formal education. For these reasons, the national workforce was unable to fuel the growing oil and gas sector, and the Omani government found it necessary to import foreign labor during the 1970s. Over the ensuing decades, however, the reliance on foreign labor has remained and has led to sharp labor market imbalances. Today the foreign-born population is 45 percent of Oman’s total population and makes up an overwhelming 89 percent of the private sector workforce. -

Iran and UAE in Yemen: Regional and Global Ambitions

Iran and UAE in Yemen: Regional and Global Ambitions Aaron Tielemans ABSTRACT fog of war to further their own regional and global interests. Moreover, some of their interests— and the strategies through which they seek to achieve them—contradict the United States’ strengthen its credibility in the Persian Gulf, it needs to critically reevaluate its strategy in the region and pay more attention to the behavior of its allies. INTRODUCTION !e narrow lens of the United States’ foreign policy in the Persian Gulf is evident when examining the civil war in Yemen. Currently, the United States is involved in the con"ict through its support for the Saudi Arabia-led coalition against the Houthi rebels. While this approach allows the United States to maintain in"uence, monitor interests, and limit its physical engagement, it also allows other actors to easily implement policies that contradict the U.S. foreign policy goals. Both Iran and the United Arab Emirates are involved in the civil war, but their behavior suggests motives that transcend the con"ict. As part of the Saudi- led coalition, the UAE has committed a signi#cant number of ground troops to the con"ict. !ough indirectly bene#ting from the U.S. support for Saudi Iran and UAE in Yemen 31 Arabia, the UAE has used the con"ict to further its own regional ambitions. Iran, which is backing the Houthi rebels, seeks to achieve its objectives without becoming entangled in the con"ict, similar to the United States. Both states use the fog of war to advance their respective hidden agendas and attempt to pro#t from the United States’ indirect engagement in the Yemeni Civil War. -

Omani Undergraduate Students', Teachers' and Tutors' Metalinguistic

Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Al Siyabi, Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education March 2019 1 Omani Undergraduate Students’, Teachers’ and Tutors’ Metalinguistic Understanding of Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Academic Writing and their Perspectives of Teaching Cohesion and Coherence Submitted by Jamila Abdullah Kharboosh Al Siyabi to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, March 2019. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signed) Jamila 2 ABSTRACT My interpretive study aims to explore how EFL university students verbally articulate their understanding of cohesion and coherence, how they perceive the teaching of cohesion and coherence and how they reflect on the way they have attempted to actualise cohesion and coherence in their EFL academic texts. The study also looks at how their writing teachers and tutors metalinguistically understand cohesion and coherence, and how they perceive issues related to the teaching/tutoring of cohesion and coherence. It has researched the situated realities of students, teachers and tutors through semi-structured interviews, and is informed by Halliday and Hasan’s (1976) taxonomy on cohesion and coherence.