Nepal Pavitra Vegetable Seed Cooperative Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Bangad Kupinde Municipality Profile 2074, Salyan All.Pdf

aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsf aguf8 s'lk08] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] sfof{no ;Nofg, ^ g+= k|b]z, g]kfn gu/ kfZj{lrq @)&$ c;f/ b'O{ zAb o; gu/kflnsf cGtu{t /x]sf ;fljs b]j:yn, afd], 3fFem/Llkkn, d"nvf]nf uf=lj=;= df k|rlnt aGuf8L ;F:s[lt / ;Nofg lhNnfnfO{ g} /fli6«o tyf cGt/f{li6«o ¿kdf lrgfpg ;kmn s'lk08]bxsf] ;+of]hgaf6 gfdfs/0f ul/Psf] aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsfsf] klxnf] k|sflzt b:tfj]hsf] ¿kdf cfpg nfu]sf] kfZj{lrq 5f]6f] ;dod} tof/L ug{ kfpFbf cToGt} v';L nfu]sf] 5 . /fHosf] k'g;{+/rgfsf] l;nl;nfdf :yflkt o; gu/kflnsfsf] oyfy{ ljBdfg cj:yf emNsfpg] kfZj{lrq tof/Ln] gu/sf] ljsf;sf] jt{dfg cj:yfnO{ lrlqt u/]sf] 5 . o:tf] lrq0fn] cfufdL lbgdf xfdLn] th'{df ug'{kg]{ gLlt tyf sfo{qmdx¿nfO{ k|fyldsLs/0f u/L xfdLnfO{ pknAw ;Lldt >f]t tyf ;fwgsf] clwstd ;b'kof]u u/L gu/ ljsf;nfO{ ult k|bfg ug{ cjZo klg ;xof]u k'¥ofpg] cfzf tyf ljZjf; lnPsf] 5' . o; cWoog k|ltj]bgn] k|foM ;a} If]q tyf j:t'ut oyfy{nfO{ ;d]6\g k|of; u/]sf] ePtfklg ;Lldt ;do tyf ;|f]t ;fwgsf] ;Ldfleq ul/Psf] cWoog cfkm}df k"0f{ x'g ;Sb}g . o;nfO{ ;do ;Gbe{cg';f/ kl/is[t / kl/dflh{t ug]{ bfloTj xfd|f] sfFwdf cfPsf] dxz'; xfdL ;a}n] ug'{ kg]{ x'G5 . of]hgfj4 ljsf;sf] cfwf/sf] ¿kdf /xg] of] kfZj{lrq ;dod} tof/ ug{ nufpg] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] ;Dk"0f{ l6d, sfo{sf/L clws[t tyf cGo j8f txdf dxTjk"0f{ lhDd]jf/L k'/f ug]{ sd{rf/L Pj+ lgjf{lrt hgk|ltlglw nufot tYofÍ pknAw u/fpg] ;Dk"0f{ ljifout sfof{no, ;+3;+:yf tyf cGo ;a}df gu/kflnsfsf] tkm{af6 cfef/ k|s6 ug{ rfxG5' . -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

35173-013: Third Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project

Due Diligence Report Project number: 35173-013 January 2016 NEP: Third Small Towns’ Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project – Birendranagar, Surkhet District Prepared by the Third Small Town Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Ministry of Urban Development Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project (STWSSSP) Project Management Office (PMO) Panipokhari, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Enhance Functionality in Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project (STWSSSP) Resettlement Due Diligence Report For Birendranagar Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project Surkhet District Kathmandu, January 2016 Submitted by: Joint Venture in Between ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd. SILT Consultants (P) Ltd. Unique Engineering P. O. Box 2147 P.O. Box 2724 Consultancy (P) Ltd. Min Bhawan, Kathmandu, Nepal Ratopul, -

Whitewater Packrafting in Western Nepal a Senior Expedition Proposal for the SUNY Plattsburgh Expeditionary Studies Program ______

Whitewater Packrafting in Western Nepal A Senior Expedition Proposal for the SUNY Plattsburgh Expeditionary Studies Program ______________________________________________________________________ Ted Tetrault Professor Gerald Isaak EXP435: Expedition Planning December 1, 2016 Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 2. Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………….... 7 3. Design and Methodology…………………………………………………………………… 16 4. Risk Management……………………………………………………………………………. 29 5. References……………………………………………………………………………………. 38 6. Appendix A: Expedition Field Manual…………………………………………………… 39 7. Appendix B: Related Maps and Documents……………………………………………. 42 8. Appendix C: Budget………………………………………………………………………… 44 9. Appendix D: Gearlist………………………………………………………………………... 47 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________________________ This expedition plan outlines a whitewater packrafting trip on the Bheri and Seti Karnali rivers in western Nepal that will serve as my capstone project for the Bachelor’s of Science in the Expeditionary Studies program at SUNY Plattsburgh. While these rivers will count as my own personal senior expedition, the trip in its entirety will also include the running of the Sun Kosi river in eastern Nepal, and that plan can be found in a separate document authored by Alex LaLonde as that segment will be serving as his capstone project for the same program. Adventure travel expeditions give us the -

Male Out-Migration, the Feminization of Agriculture, and Integrated Pest Management in the Nepali Mid-Hills

“When He Comes Home, Then He Can Decide”: Male Out-Migration, the Feminization of Agriculture, and Integrated Pest Management in the Nepali Mid-Hills Kaitlyn A. Spangler Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Geography Maria Elisa Christie Luke Juran Ralph Hall April 20, 2018 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: feminization of agriculture, collective spaces, integrated pest management, agrarian change, feminist political ecology Copyright © Kaitlyn A. Spangler, 2018 “When He Comes Home, Then He Can Decide”: Male Out-Migration, the Feminization of Agriculture, and Integrated Pest Management in the Nepali Mid-Hills Kaitlyn A. Spangler ABSTRACT (Academic) As part of a USAID-funded integrated pest management (IPM) project, this thesis presents research conducted across four communities in midwestern Nepal We conducted semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and participant observation with local farmers and NGOs. Grounded in feminist political ecology (FPE) and drawing on the social relations approach (SRA), we sought to engage with the feminization of agriculture narrative and understand how it interacts with IPM practices and decision- making. This research responds to a growing interest within development in the feminization of agriculture as a potentially empowering or disempowering global process of change, conceptualized through the ways that male out-migration affects the labor and decision-making roles of women and other household members left behind on the farm. We find that contextual factors change the implications of the feminization of agriculture narrative. Co-residence with in-laws and varied migration patterns influence the dynamic nature of household structure and headship. -

Pdf | 268.57 Kb

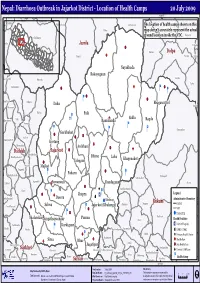

Nepal: Diarrhoea Outbreak in Jajarkot District - Location of Health Camps 20 July 2009 82°30'0"E Jubika Ramchuli Pakha Dah Malikathota Guthichaur The location of health camps shown on this Haku map doesn't accuratelyRIMI represent the actual ground location inside the VDC. Kaigaun Chilkhaya Gela Jumla &! Pahada Kalikot Sarmi Dolpa Tamti GF Narku Likhu Nayakbada Rokayagaun Kalika Kasikandh Odanku Laha GF ! Baluwatar &! Ý & Ý &! &! Raniban Odhari Ý Bhagawatitol Daha Suhun Bhawani Kalika Paik ; &! Sakla Kharigera Toli Ý Ramidanda Ragda Nomule Ý Ý Ý Ý Gautamkot &! Garkhakot ! Salleri &! & Narayan N.P. Kortang GF Chauratha Archhani &! GF Dailekh Jajarkot &! Moheltolee Dhime Bindhyabasini Laha Khagenakot &! Talegaun Room Majkot Pagnath ! Padaru & BadaBhairab Ý Ý Syalagadi AathbisKot Jaganath Lakuri &!Suwanauli Dandagaun Sisne ! & h AathbisDanda Katti ! Jhapra Æ Ý Legend & Ý GF × q DadaParajul Dasera Khalanga Administrative Boundary ! Rukum Jang Ghetma Magma District AwalParajul ! Salma Jajarkot (Khalanga) & Ý &! VDC Ý &! ! District HQ Thalarekar &! Punma Baflikot Jungathapachaur Duli Health Facilities Æ Pwang Lalikanda Karkigaun Pipalq District Hospital Piladi Matela Ý PurtimKanda Garayala × DPHO / DHO GF Ý Jhula ; Primary Health Centre Ratu GF Kotjahari GF GF Sima Bhur Health Post Simli ! AWALCHING Jagatipur & SubPokhara Health Post Rangsi Surkhet Syalapakha Garpan Ghoreta Chaurjahari( (Bijayashwari) h District Cold Room Kholagaun MusikotKhalanga( Ranibas Arma Chhiwang Kanda Pamka Bame Health Camp Rajena Agragaun Suikot Sankha Sobha Satakhani Kafalkot Salyan Kalagaun Nuwakot Pyaugha Bhalakacha Ý 82°30'0"E Produced on: 2 July 2009 Disclaimers: Map Produced by OCHA, Nepal Map Doc Name: D_Outbreak_Jajarkot_3W_A4_21072009_v01 The boundaries and names shown and the 02 4 Km Data Source(s): Data are collected from DPHO, UN Agencies and I/NGOs Web Resources: http://www.un.org.np designations used on this map do not imply official I Boundaries - Department of Survey, Nepal Projection/Datum: Geographic/Everest 1830 endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

An Assessment of School Deworming Program in Surkhet and Kailali District

2010 AN ASSESSMENT OF SCHOOL DEWORMING PROGRAM IN SURKHET AND KAILALI DISTRICT 2010 Nepal Health Research Council Acknowledgement I am grateful to all the members of steering committee of Nutrition unit of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) for their efforts and commitment for the completion of this report. I am greatly indebted to Dr. Laxmi Raj Pathak, Dr. Baburam Marasini and Mr. Rajkumar Pokharel for their invaluable advice in this project. I would like to give thanks to Dr. Shanker Pratap Singh, Member Secretary for his kind contribution in this study. I express my special thanks to core research team, Dr. Gajananda Prakash Bhandari, Senior Epidemiologist, Ms. Femila Sapkota, Research Officer, Ms. Chandika Shrestha Assistant Research Officer and Ms. Kritika Paudel, Senior Research Assistant of Nepal Health Research Council for their great effort in proposal development, data collection, and data analysis and further more in completion of research project. I extend my sincere thanks to the D(P)HO and DEO office of Surkhet and Kailali district. Similarly, I am very pleased to acknowledge all the school teachers, parents and health institution incharge of the selected schools and health institution who helped by providing the valuable data and information without which the research could not have been accomplished. I am highly indebted to resource person and school inspector of DEO Surkhet and Kailali for their help during data collection. Similarly, special thanks go to BaSE office, Kailali for the valuable information. I express thanks to all the enumerators for their endless labor and hard working during data collection. Lastly, I am grateful to all those direct and indirect hands for help and support in successful completion of the study. -

![आकाश स िंह राम प्रघट स िंह राकेश स िंह P]G Axfb"/ Af]Xf]/F L;Krg](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4868/p-g-axfb-af-xf-f-l-krg-1494868.webp)

आकाश स िंह राम प्रघट स िंह राकेश स िंह P]G Axfb"/ Af]Xf]/F L;Krg

खुला प्रलतयोलगता配मक परीक्षाको वीकृ त नामावली वबज्ञापन नं. : २०७७/७८/३४ (कर्ाला ी प्रदेश) तह : ३ पदः कलनष्ठ सहायक (गो쥍ड टेटर) सम्륍मललत हुन रोल नं. उ륍मेदवारको नाम उ륍मेदवारको नाम (देवनागरीमा) ललंग थायी म्ि쥍ला थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स बािेको नाम बाबुको नाम चाहेको समूह 1 AAKASH SINGH आकाश स िंह Male ख쥍ु ला Banke Nepalgunj Sub-Metropolitian City राम प्रघट स िंह राके श स िंह 2 AIN BAHADUR BOHARA P]g axfb"/ af]xf]/f Male ख쥍ु ला Jumla Patarasi l;krGb| af]xf]/f ;fk{ nfn af]xf]/f 3 AISHWARYA SHAHI ऐश्वर् य शाही Female ख쥍ु ला Surkhet Gurbhakot असिपाल शाही बृज ब शाही 4 AJAR ALI MIYA अजार अली समर्ााँ Male ख쥍ु ला Dailekh Bhairabi आशादली समर्ााँ मर्ु यदली समर्ााँ 5 ALINA BAIGAR Plngf a}uf/ Female ख쥍ु ला, दललत Surkhet Birendranagar bn axfb"/ a}uf/ /d]z a}uf/ 6 ANIL BISHWOKARMA असिल सिश्वकमाय Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Salyan Marke VDC ^f]k axfb'/ ;"gf/ शासलकराम सिश्वकमाय 7 ANUP BISHWOKARMA cg"k ljZjsdf{ Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Dang Deokhuri Gadhawa alx/f sfdL t]h] sfdL 8 ARBINA THARU clj{gf yf? Female ख쥍ु ला Bardiya Geruwa dga'emfjg yf? x]jtnfn yf? 9 BABITA PANGALI alatf k+ufnL Female ख쥍ु ला Surkhet Jarbuta dlg/fd k+ufnL ofd k|;fb k+ufnL 10 BHAKTA RAJ BHATTA eSt /fh e§ Male ख쥍ु ला Doti Ranagaun 6Lsf /fd e§ nId0f k||;fb e§ 11 BHANU BHAKTA ROKAYA भािभु क्त रोकार्ा Male ख쥍ु ला Bajura Himali उसजरे रोकार्ा चन्द्र बहादरु रोकार्ा 12 BHARAT NEPALI भरर् िेपाली Male ख쥍ु ला, दललत Surkhet Gutu राम स िं दमाई गाेेपाल स िं िेपाली 13 BHARAT RAWAL भरर् रािल Male ख쥍ु ला Mugu Khatyad RM जर् रु रािल जर्लाल रािल 14 BHUPENDRA BAHADUR CHAND e"k]Gb| axfb"/ rGb Male ख쥍ु ला Dailekh sinhasain etm -

Progress Report on Procurement, 2013/14 (JAR 2015)

Form B ongoing Progress Report on Procurement, 2013/14 (JAR 2015) Annex 3.4: Implementation Progress on Civil Works Planned Before 2013/14 (Expenditure Details) Progress shown is up to mid-July 2014 Government of Nepal Ministry of Urban Development DUDBC, Health Building Unit Implementation Progress Report for Civil Works Planned Before 2070/71 (Ongoing) Trimester Period: Annual (Form B) Currency: in NPR and in 000's Amount DUDBC Division Authorized Contract Amount Paid to SN ID Description District Budget Head Exp Head Contract ID Budget Allocation Release Amount Expenditure Exp % Supplier/ Contractor Nationality invoice to Status Physical Progress Office Budget date Currency Value date Yakthumka/Gajurmukhi/Sewalun Worked in Finishing/ Electrical 1 0324 Ilam PHCC Bldg. Construction, Tellok, Taplejung Taplejung 3708044 29221 NHSP-Ilam-2065/066-324 100 100 0.00 0 - g/Thebe JV Nepal NRs 38,749.31 - 30,410.16 / Sanitary 90 Worked in Finishing/ Electrical 2 0328 Ilam Gauradaha HP Bldg. Const., Jhapa Jhapa 3708044 29221 NHSP-Ilam-2066/067-328 3494 3494 0.00 3319 94.99 Kunsaling / Puspanjali JV Nepal NRs 15,216.57 - 7,619.00 / Sanitary 90 3 0329 Ilam Kafalbote HP Bldg. Const., Panchthar Panchthar 3708044 29221 NHSP-Ilam-2066/067-329 4765 4765 0.00 4537 95.22 Kankai Builders Nepal NRs 20,775.88 - 19,339.49 Work Completed 100 Worked upto RCC in 1st floor 4 0330 Ilam Mangalbare PHCC Bldg. Const., Ilam Ilam 3708044 29221 NHSP-Ilam-2066/067-330 8000 8000 0.00 7211 90.14 Danfe / Mahadev Khimti JV Nepal NRs 38,761.31 - 14,490.00 / Roofing 65 Shankarmali / Puspanjali / 5 0331 Ilam Khajurgachhi PHCC Bldg. -

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (Fiscal Year 2017/18)

LoanLoan No.: No.: 796−NP 796−NP GrantGrant No.: No.: DSF−8050−NP DSF−8050−NP Government of Nepal Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development High Value Agriculture Project in Hill and Mountain Areas (HVAP) ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (Fiscal Year 2017/18) Implementing Partners Connecting People’s Capacities Project Management Unit (PMU) Birendranagar, Surkhet, Nepal Phone No.: 977-83-520038, Fax No.: 977-83-525403 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hvap.gov.np September 2018 September, £017 Government of Nepal Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2017/18 (16 July 2017 to 17 July 2018) HIGH VALUE AGRICULTURE PROJECT IN HILL AND MOUNTAIN AREAS (HVAP) Project Management Unit Birendranagar, Surkhet, Nepal Phone No.:977-83-520038, Fax No.:977-83-525403 Email: [email protected] www.hvap.gov.np September, 2018 (Annual Progress Report 2017/18) September 2018 Project at a Glance Country Nepal Title of the Report Annual Progress Report 2017/18 High Value Agriculture Project In Hill and Mountain Areas Project Title (HVAP) Project Number Loan No.: 796-NP; Grant No.: DSF-8050-NP Donor Agency International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Ministry of Agriculture and LIvestock Development, Executing Agency Government of Nepal Partners SNV-Nepal and Agro Enterprise Centre Location of the Project 6 Districts from Province 6 and 1 District from Privince 7 Fiscal Year/Reporting Year 2017/18 Reporting Period 16July 2017 to 17July 2018 Year of Implementation 8th Year Total Project Budget (US$) 18.87 Million Date of Loan Effectiveness 5 July 2010 Date of Project Start 6 Feb 2011 Project Duration 7.5 Years Date of Project Completion 30 September 2018 Date of Financing Closing 31 March 2019 Budget of FY 2016/17 Year NRs. -

Politics of R Esistance

Politics of Resistance Politics Tis book illustrates an exciting approach to understanding both Indigenous Peoples of Nepal are searching for the state momentous and everyday events in the history of South Asia. It which recognizes and refects their identities. Exclusion of advances notions of rupture and repair to comprehend the afermath indigenous peoples in the ruling apparatus and from resources of natural, social and personal disasters, and demonstrates the of the “modern states,” and absence of their representation and generality of the approach by seeking their historical resolution. belongingness to its structures and processes have been sources Te introduction of rice milling technology in a rural landscape of conficts. Indigenous peoples are engaged in resistance in Bengal,movements the post-cold as the warstate global has been shi factive in international in destroying, relations, instead of the assassinationbuilding, their attempt political, on a economicjournalist and in acultural rented institutions.city house inThe Kathmandu,new constitution the alternate of 2015and simultaneousfailed to address existence the issues, of violencehence the in non-violentongoing movements,struggle for political,a fash feconomic,ood caused and by cultural torrential rights rains and in the plainsdemocratization of Nepal, theof the closure country. of a China-India border afer the army invasionIf the in Tibet,country and belongs the appearance to all, if the of outsiderspeople have in andemocratic ethnic Taru hinterlandvalues, the – indigenous scholars in peoples’ this volume agenda have would analysed become the a origins, common anatomiesagenda and ofdevelopment all. If the state of these is democratic events as andruptures inclusive, and itraised would interestingaddress questions the issue regarding of justice theirto all.