Review Article Kennedy's Alliance for Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

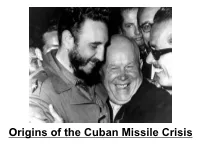

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

BRAZIL AND THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS: US-BRAZILIAN FINANCIAL RELATIONS DURING THE FORMULATION OF JOÃO GOULART‟S THREE-YEAR PLAN (1962)* Felipe Pereira Loureiro Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations, University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), Brazil [email protected] Presented for the panel “New Perspectives on Latin America‟s Cold War” at the FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference, Buenos Aires, 23 to 25 July, 2014 ABSTRACT The paper aims to analyze US-Brazilian financial relations during the formulation of President João Goulart‟s Three-Year Plan (September to December 1962). Brazil was facing severe economic disequilibria in the early 1960s, such as a rising inflation and a balance of payments constrain. The Three-Year Plan sought to tackle these problems without compromising growth and through structural reforms. Although these were the guiding principles of the Alliance for Progress, President John F. Kennedy‟s economic aid program for Latin America, Washington did not offer assistance in adequate conditions and in a sufficient amount for Brazil. The paper argues the causes of the US attitude lay in the period of formulation of the Three-Year Plan, when President Goulart threatened to increase economic links with the Soviet bloc if Washington did not provide aid according to the country‟s needs. As a result, the US hardened its financial approach to entice a change in the political orientation of the Brazilian government. The US tough stand fostered the abandonment of the Three-Year Plan, opening the way for the crisis of Brazil‟s postwar democracy, and for a 21-year military regime in the country. -

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe a Film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe A film by Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDE William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers NEw YorK , 2010 Dear Colleague, William kunstler: Disturbing the Universe grew out of conver - sations that Emily and I began having about our father and his impact on our lives. It was 2005, 10 years after his death, and Hurricane Katrina had just shredded the veneer that covered racism in America. when we were growing up, our parents imbued us with a strong sense of personal responsibility. we wanted to fight injustice; we just didn’t know what path to take. I think both Emily and I were afraid of trying to live up to our father’s accomplishments. It was in a small, dusty Texas town that we found our path. In 1999, an unlawful drug sting imprisoned more than 20 percent of Tulia’s African American population. The injustice of the incar - cerations shocked us, and the fury and eloquence of family members left behind moved us beyond sympathy to action. while our father lived in front of news cameras, we found our place behind the lens. our film, Tulia, Texas: Scenes from the Filmmakers Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler. Photo courtesy of Maddy Miller Drug War helped exonerate 46 people. one day when we were driving around Tulia, hunting leads and interviews, Emily turned to me. “I think I could be happy doing this for the rest of my life,” she said, giving voice to something we had both been thinking. -

July-August 2017

July-August 2017 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume VIII. Issue 5. President John F. Kennedy and his son, John Jr., 1963 (AP Photo) In this issue: President John F. Kennedy Zoom in on America The Life of John F. Kennedy John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massa- During WWII John applied and was accepted into the na- chusetts, on May 29, 1917 as the second of nine children vy, despite a history of poor health. He was commander of born into the family of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose PT-100, which on August 2, 1943, was hit and sunk by a Fitzgerald Kennedy. John was often called “Jack”. The Japanese destroyer. Despite injuries to his back, an ail- Kennedys had a powerful impact on America. John Ken- ment that would haunt him to the end of his life, Kennedy nedy’s great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, emigrated managed to rescue his surviving crew members and was from Ireland to Boston in 1849 and worked as a barrel declared a “hero” by the New York Times. A year later Joe maker. His grandfather, Patrick Joseph (P.J.) Kennedy, was killed on a volunteer mission in Europe when his air- achieved success first in the saloon and liquor-import craft exploded. businesses, and then in banking. His father, Joseph Pat- Joseph Patrick now placed all his hopes on John. In 1946, rick Kennedy, made investments in banking, ship building, John F. Kennedy successfully ran for the same seat in real estate, liquor importing, and motion pictures and be- Congress, which his grandfather held nearly five decades came one of the richest men in America. -

The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

The Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress and the Burdens of the Marshall Plan Christopher Hickman Latin America is irrevocably committed to the quest for modernization.1 The Marshall Plan was, and the Alliance is, a joint enterprise undertaken by a group of nations with a common cultural heritage, a common opposition to communism and a strong community of interest in the specific goals of the program.2 History is more a storehouse of caveats than of patented remedies for the ills of mankind.3 The United States and its Marshall Plan (1948–1952), or European Recovery Program (ERP), helped create sturdy Cold War partners through the economic rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan, even as mere symbol and sign of U.S. commitment, had a crucial role in re-vitalizing war-torn Europe and in capturing the allegiance of prospective allies. Instituting and carrying out the European recovery mea- sures involved, as Dean Acheson put it, “ac- tion in truly heroic mold.”4 The Marshall Plan quickly became, in every way, a paradigmatic “counter-force” George Kennan had requested in his influential July 1947 Foreign Affairs ar- President John F. Kennedy announces the ticle. Few historians would disagree with the Alliance for Progress on March 13, 1961. Christopher Hickman is a visiting assistant professor of history at the University of North Florida. I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2008 Policy History Conference in St. Louis, Missouri. I appreciate the feedback of panel chair and panel commentator Robert McMahon of The Ohio State University. I also benefited from the kind financial assistance of the John F. -

REGISTER Further Information Or Reser Ground Will Be Broken Sunday, Jan

Laywomento Sponsor Member of 'Audit Bureau of Circulation Loretto Heights Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1951— Permission to Reproduce, Except on Press Speaker Day of Recollection Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue. Work to Be Started In Littleton Jan. 27 The 17th annual day o f recol lection will be sponsored by the Catholic Laywomen’s Retreat as sociation Sunday, Jan. 27, iir St. Mary’s church and hall, Littleton. DENVER CATHOLIC The retreat Jhaster will be the On St. John s Church Rev. Frederick Mann, C.SS.R., of S t Joseph’s Redemptorist parish, Denver. « Transportation may be pbtained Gtound-Breaking Ceremonies Jan. 13 via either Trailways or tramway bus. The fee for the day is $2. REGISTER Further information or reser Ground will be broken Sunday, Jan. 13, at 3 o ’clock for the new Church vations may be obtained by calling of St. John the Eyangelist in East Denver at E. Seventh avenue parkway and Mrs. Thomas Carroll, PE. 5842, or VOL. XLVIl. No. 21. THURSDAY, JANUARY 10, 1952 DENVER, dOLO. Littleton 154-R. Elizabeth street. The Rt. Rev. Monsignor John P. Moran, pastor, announced that construction will begin immediately on the long-needed new church. The construction contract has been awarded to the Originality, Co-Operatioa Keynote All-Parochial Play Frank J. Kirchhof Construction company of Denver, who submitted the low base bid of $300,400. The electrical and + + + + + Co-operation is the keynote + + + + + heating contracts increase this figure to $345,688. John K. Monroe of the all-parochial play pro is the architect o f the structure, which is patterned on modernized duction. -

Anuario 2020

REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA ANUARIO REAL AC ADEMIA ESPAÑOLA ANUARIO REAL ACADEMIA E SPAÑOLA Felipe IV, Madrid C E N T RO D E ESTUDIOS Serrano, - Madrid http://www.rae.es Medalla de la Real Academia Española. En uso desde . Emblema: un crisol en el fuego con la leyenda Limpia, fija y da esplendor Portada de la primera edición de Fundación y estatutos de la Real Academia Española (). ORIGEN DE LA REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA La Real Academia Española se fundó el año por iniciativa del Excmo. Sr. D. Juan Manuel Fer- nández Pacheco, marqués de Villena. Se aprobó la fundación por Real Cédula de Felipe V, expe- dida a de octubre de . En ella se autorizó a la Academia para formar sus estatutos y se con- cedieron varios privilegios a los académicos y a la corporación. Esta adoptó por divisa un crisol puesto al fuego, con la leyenda Limpia, fija y da esplendor. La Academia tuvo, desde luego, la prerroga- tiva de consultar al rey en la forma de los Supre- mos Tribunales, y los académicos gozaron de las preeminencias y exenciones concedidas a la ser- vidumbre de la Casa Real. El de diciembre de se le concedió la dotación de reales anuales para sus publicaciones, y el rey Fernando VI le dio facultad para publicar sus obras y las de sus miembros sin censura previa. En , el monarca cedió a la corporación para sus juntas, que hasta entonces se habían celebrado en casa de sus directores, una habitación en la Real Casa del Tesoro; el de agosto de le fue con- cedida por Carlos IV la casa de la calle de Val- verde, señalada actualmente con el número ; y allí permaneció hasta su traslado al edificio que hoy ocupa, construido de nueva planta para este cuerpo literario e inaugurado el de abril de con la asistencia de la regente María Cristina de Habsburgo y el rey Alfonso XIII. -

Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatã¡N Katherine Warming Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatán Katherine Warming Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Warming, Katherine, "Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatán" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16484. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16484 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tourist-Technicians: Civilian diplomacy, tourism, and development in Cold War Yucatán by Katherine Warming A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Bonar Hernández, Major Professor Michael Christopher Low Amy Erica Smith The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright © Katherine Warming, 2018. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2. HISTORIOGRAPHY 7 CHAPTER 3. THE POWER OF PEOPLE: EMERGENCE OF THE CIVILIAN 13 PARTNERSHIP MODEL CHAPTER 4. -

Redalyc.Descripción De La Ciudad Y Su Tiempo Por Los Poetas Y La Poesía: El Caso Chileno

Literatura y Lingüística ISSN: 0716-5811 [email protected] Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez Chile Morales, Andrés Descripción de la ciudad y su tiempo por los poetas y la poesía: el caso chileno Literatura y Lingüística, núm. 13, 2001, p. 0 Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez Santiago, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35201305 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto DESCRIPCIÓN DE LA CIUDAD Y SU TIEMPO POR LOS POETAS Y LA POESÍA: EL CASO CHILENO Andrés Morales Univ. de Chile / Univ. Diego Portales Resumen El presente trabajo1 aborda panorámicamente el tópico de la ciudad en buena parte de la poesía chilena escrita por la generación de 1957 hasta nuestros días. El objetivo central es demostrar cómo este tema ha sido capital para el desarrollo de las promociones del '72, del '87 y del 2002 y cuáles han sido las modalidades que éste ha adoptado en el transcurso de la evolución de este género en Chile. Abstract The following study (published at the XX Congress of Poets in Thessaloniki, Greece in August 2000) approaches the theme of 'the city' in most of Chilean poetry written by the generation of 1957 until nowadays. The main objective is to demonstrate the mechanism by which this topic has been essential for the development of the '72, '87 and year 2002 generations, and to discover which have been the modalities adopted in the evolution of the gender in Chile. -

The Rules of the Game: Allende's Chile, the United States and Cuba, 1970-1973

The Rules of the Game: Allende’s Chile, the United States and Cuba, 1970-1973. Tanya Harmer London School of Economics and Political Science February 2008 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in International History, Department of international History, LSE. Word Count (excluding bibliography): 99,984. 1 UMI Number: U506B05 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U506305 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ti4es^ 5 F m Library British Litiwy o* Pivam* and Economic Sc«kk* li 3 5 \ q g Abstract This thesis is an international history of Chile and inter-American relations during the presidency of Salvador Allende. On the one hand, it investigates the impact external actors and international affairs had on Chilean politics up to and immediately following the brutal coup d’etat that overthrew Allende on 11 September 1973. On the other hand, it explores how the rise and fall of Allende’s peaceful democratic road to socialism affected the Cold War in Latin America and international affairs beyond.