White Gold the True Cost of Cotton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

Uzbekistan at Ten

UZBEKISTAN AT TEN: REPRESSION AND INSTABILITY 21 August 2001 ICG Asia Report No 21 Osh/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF UZBEKISTAN ..............................................................................................................................................................i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.....................................................................................................ii I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................1 II. UZBEKISTAN’S FRACTURED POLITICAL LANDSCAPE.....................................................................................3 A. SECULAR DEMOCRATIC OPPOSITION ........................................................................................................4 B. OFFICIAL PARTIES .....................................................................................................................................8 C. ISLAMIC OPPOSITION...............................................................................................................................12 III. REGIONAL, CLAN AND ETHNIC RIVALRIES.......................................................................................................16 IV. A RISING TIDE OF SOCIAL DISCONTENT ............................................................................................................21 V. EXTERNAL FORCES....................................................................................................................................................26 -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Asia Briefing N°54 Bishkek/Brussels, 6 November 2006 Uzbekistan: Europe’s Sanctions Matter I. OVERVIEW in their production, or to the national budget, but to the regime itself and its key allies, particularly those in the security services. Perhaps motivated by an increasing After the indiscriminate killing of civilians by Uzbek sense of insecurity, the regime has begun looting some security forces in the city of Andijon in 2005, the of its foreign joint-venture partners. Shuttle trading and European Union imposed targeted sanctions on the labour migration to Russia and Kazakhstan are increasingly government of President Islam Karimov. EU leaders threatened economic lifelines for millions of Uzbeks. called for Uzbekistan to allow an international investigation into the massacre, stop show trials and improve its human Rather than take serious measures to improve conditions, rights record. Now a number of EU member states, President Karimov has resorted to scapegoating and principally Germany, are pressing to lift or weaken the cosmetic changes, such as the October 2006 firing of sanctions, as early as this month. The Karimov government Andijon governor Saydullo Begaliyev, whom he has has done nothing to justify such an approach. Normalisation publicly called partially responsible for the previous of relations should come on EU terms, not those of year’s events. On the whole, however, Karimov continues Karimov. Moreover, his dictatorship is looking increasingly to deny that his regime’s policies were in any way at fragile, and serious thought should be given to facing the fault, while the same abuses are unchecked in other consequences of its ultimate collapse, including the impact provinces. -

Central Asia's Destructive Monoculture

THE CURSE OF COTTON: CENTRAL ASIA'S DESTRUCTIVE MONOCULTURE Asia Report N°93 -- 28 February 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE ECONOMICS OF COTTON............................................................................... 2 A. UZBEKISTAN .........................................................................................................................2 B. TAJIKISTAN...........................................................................................................................6 C. TURKMENISTAN ..................................................................................................................10 III. THE POLITICS OF COTTON................................................................................... 12 A. UZBEKISTAN .......................................................................................................................12 B. TAJIKISTAN.........................................................................................................................14 C. TURKMENISTAN ..................................................................................................................15 IV. SOCIAL COSTS........................................................................................................... 16 A. WOMEN AND COTTON.........................................................................................................16 -

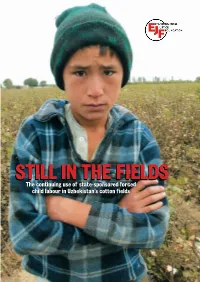

Still in the Fields: the Continuing Use

sitf 009 4/22/09 2:06 PM Page 1 STILLSTILL ININ THETHE FIELDSFIELDS The continuing use of state-sponsored forced child labour in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields sitf 009 4/22/09 2:06 PM Page 2 © www.un.org STILL IN THE FIELDS The continuing use of state-sponsored forced child labour in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields CONTENTS Executive summary Introduction Pressure to produce harvest – region by region Hard work, poor health & squalid living conditions… for no pay? Not only children Conclusions Recommendations References Acknowledgements The Environmental Justice Foundation This report was researched, written and produced is a UK-based non-governmental by the Environmental Justice Foundation. organisation. More information about Design Dan Brown ([email protected]) EJF’s work and pdf versions of this report can be found at www.ejfoundation.org. Cover photo © Thomas Grabka Comments on the report, requests for Tel 44 (0) 20 7359 0440 Back cover photos: (top) © EJF; further copies or specific queries about (bottom) © Thomas Grabka [email protected] EJF should be directed to www.ejfoundation.org [email protected]. Printed on % post-consumer waste recycled paper. This document should be cited as: EJF. Still in the fields: the continuing EJF would like to thank all those people and use of state-sponsored forced child labour in organisations who have given their valuable time Uzbekistan’s cotton fields. Environmental and assistance with information and visual Justice Foundation, London, UK. materials used in this report. We in no way imply these people endorse the report or its findings. In ISBN No. -

The Schroeder Institute in Uzbekistan: Breeding and Germplasm Collections

COVER STORY HORTSCIENCE 39(5):917–921. 2004. (Cannabis sativa L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), cereal crops, and forage crops. Later, separate research institutes were established to focus on The Schroeder Institute in Uzbekistan: individual crops and initiate specifi c breed- ing programs. TAES was the fi rst institute in Breeding and Germplasm Collections Central Asia established for studies of genet- ics/breeding and the cultural management of Mirmahsud M. Mirzaev and Uri M. Djavacynce fruits, grapes, and nuts. Richard R. Schroeder Uzbek Research Institute of Fruit Growing, Viticulture, and Schroeder developed improved cultivars of Wine Production, 700000 Tashkent, Glavpochta, ab #16, Republic of Uzbekistan cotton, rice, corn (Zea mays L.), and other crops (Schroeder, 1956). In tree fruits, he focused 1 2 David E. Zaurov, Joseph C. Goffreda, Thomas J. Orton, Edward G. on improving cold-hardiness, resistance to dis- Remmers, and C. Reed Funk eases and insects, and yield. In 1911, Schroeder Department of Plant Biology and Pathology, Cook College, Rutgers University, participated in the 7th International Congress New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8520 of Arid Lands in the United States for cotton and orchard crops. While in the United States, Additional index words. germplasm, apples, walnuts, peach, grapes, plums, almonds, he collected seeds of legumes, sorghum, and apricots, pistachios, breeding cotton cultivars and evaluated them in Central Asia. Shortly thereafter, Schroeder published Central Asia was largely isolated from the Uzbek Scientifi c Research Institute of Plant an agricultural monograph that was widely western world from the early 1800s until 1991, Industry (former branch of VIR) and Uzbek distributed throughout the Russian Empire and, when the former Soviet Union was dissolved. -

Uzbekistan, 2016

Michel GERVAIS [email protected] From 23/04/2016 to 13/05/2016 with my wife we visited Uzbekistan. Our targets were tulips, mammals and 3 historic cities. With the very clement winter Uzbekistan experienced this year, there was a month of delay to see tulips in bloom in the desert ! No problem for the monuments ! Regardless of the weather report they are always there ! For mammals we knew that it would be difficult ! We had found neither trip report nor book to help us prepare… Another complication : nature conservation is not a priority for Uzbekistan. Hunting seems to be a common practice, if it is not poaching ! For example in the historic city of Khiva, tourists buy Caps made of skin of wolf, fox and snow leopard !!!! Other complication : as a foreigner you are obliged to stay in accredited accommodations, which do not exist outside tourist zone ! Entering reserves and parks is very difficult for tourist and in some case it is forbidden ! So we contacted a local travel Agency and specially Salokhiddin who is not a naturalist but very interested in wildlife (for more informations please contact me). For mammals, he planned for us a trip 130 km north of Uchquduq with hunters, staying first near Aydarkul lake, then in moutains of Nouratau and finally in Chimgan (Foothills of the mountain Thian Chan). Thian Chan was in the clouds during the 3 days of our visit. So we don’t see any mammals exept one little rodent with very long incisors that was not identified ! In Nouratau we stayed in Hayat near the reserve of Nuratinsky which unfortunately we were not authorized to enter ! On crests we were able to observe several Argali ( Ovis severtzovi ). -

State of Forests of the Caucasus and Central Asia

State of Forests of the Caucasus and Central Asia State of Forests of the Caucasus and Central Asia GENEVA TIMBER AND FOREST STUDY PAPER Overview of forests and sustainable forest management in the Caucasus and Central Asia region New York and Geneva, 2019 2 State of Forests of the Caucasus and Central Asia COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMER Copyright© 2019 United Nations and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved worldwide. The designations employed in UNECE and FAO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) or the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal status of any country; area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this study and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and its publication does not constitute an endorsement by UNECE or FAO of the opinions expressed. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply their endorsement by UNECE or FAO, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. This work is copublished by the United Nations (UNECE) and FAO. ABSTRACT The study on the state of forests in the Caucasus and Central Asia aims to present the forest resources and the forest sector of the region, including trends in, and pressures on the resource, to describe the policies and institutions for the forest sector in the region and to list the major challenges the sector faces, and the policy responses in place or planned. -

Mission to Uzbekistan 6-11 October 2017

Appendix V.II.C - 17GC/E/5 Mission to Uzbekistan 6-11 October 2017 General context 1. In spring 2017 the ITUC delegation visited Uzbekistan and met with FTUU the leadership, visited several organisations where unions were operating and also informally discussed activities of the trade unions with human rights defenders. That mission formulated recommendations to the FTUU and the FTUU developed a plan of work to address them. That plan was communicated to the ITUC in summer 2017. On that basis the FTUU invited ITUC to take part in a set of activities they run as a part of the World Day for Decent Work campaign. 2. leave the country for international voyages is to be gradually lifted. Foreign relations with neighbouring countries were relaunched (including Tajikistan, despite water conflict). Some political dissidents were released. Local currency, sum, was made convertible. That move improved export and brought investment promises (the level of foreign investments already grew remarkably this year). It abolished the black market, facilitated transparent exchange rate. However, official value of Sum was decreased in two times. That did not resulted in price increase yet as the main products for population are produced in the country and not imported. The government changed its approach to Uzbek citizens abroad. Previously, gnised responsibilities for them. For the first time the government provided immediate assistance to the victims of the tragic road accident in Russia. In general relations with neighbouring countries improved significantly, even with Tajikistan despite the water conflict. Privatisation of dozens healthcare facilities was announced, special economic zones established where industrial parks shall be opened. -

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Uzbekistan

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Uzbekistan N.B. To check the official, current database of UN/LOCODEs see: https://www.unece.org/cefact/locode/service/location.html UN/LOCODE Location Name State Functionality Status Coordinatesi UZ 6BT Kungrad QR Road terminal; Recognised location 4304N 05854E UZ AGN Ohangaron TO Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4054N 06938E UZ AKT Akaltyn Port; Road terminal; Recognised location 4126N 06104E UZ ALK Almalyk Road terminal; Request under consideration UZ ALT Altyaryk FA Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4023N 07128E UZ ASA Asaka AN Port; Road terminal; Request under consideration 4038N 07214E UZ AST Astana XO Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4120N 06036E UZ AZN Andizhan Airport; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC UZ BHK Bukhara Airport; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC UZ CHU Chukur-Say TO Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4122N 06913E UZ CKT Chimkent FA Road terminal; Recognised location 4029N 07138E UZ FEG Fergana Airport; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC UZ GST Guliston Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4030N 06847E UZ JIZ Jizzakh JI Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4006N 06750E UZ KAM Kamashi QA Road terminal; Recognised location 3849N 06627E UZ KBZ Karaulbazar Road terminal; Recognised location 3929N 06447E UZ KGS Kengsoy QA Road terminal; Recognised location 3821N 06551E UZ KHM Khamza Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 4025N 07130E UZ KKH Khanabad QA Road terminal; -

Karmana Tumani Nurota Tumani

O‘zbekiston Respublikasi Yoshlar ishlari agentligining hududiy boshqarmalari, tuman bo‘limlari, hududlardagi yoshlar bilan ishlash bo‘yicha tashkil etilgan shtablar va sektorlar to‘g‘risida MA’LUMOT O‘zbekiston Respublikasi Yoshlar ishlari agentligining hududiy boshqarmalari manzil va Shtab (mazili ma’sul xodim F.I.Sh tel Sektorlar (mazili ma’sul xodim F.I.Sh tel № telefon raqamlari raqami) raqami) Tuman shahar Viloyat boshqarmasi bo‘lim raxbari (mazili F.I.Sh tel raqami) Navoiy shahar 1.Hokim sektori Navoiy shahar 2-Maktab binosi 1. M.Xudoyberdiyev 99-750-15-06 2.Prokuror sektori Navoiy shahar Me`morlar Navoiy shahar A.Temur ko‘chasi 4a-uy. 2. Navoiy shahar A.Temur ko‘chasi 4a-uy kochasi Yoshlar ishlar agentligi Navoiy shahar Navoiy viloyati Shtab boshlig`i U.Murodullayev A.Avazov 99-575-09-69 bo‘limi boshlig‘i X.Hakimov 90-732-27-28 3.Ichki ishlar Sektori Navoiy shahar G`alaba 3. (99)-750-88-10 shoh kochasi 224-a-uy F. Normurodov 4.Soliq sektori Navoiy shahar Spitamin ko`chasi 4. 14-uy O.Xasanov 97-365-52-88 Karmana tumani 1.Hokim sektori Karmana tumani Talqoq MFY 5. Z.Tursunov 99 5901031 2.Prokuror sektori Karmana tuman Jaloyir MFY 6. Karmana tumani Talqoq MFY Karmana tumani Talqoq MFY Sh.Fayziyev 99 3378886 Navoiy viloyati Yudupov Fuzoyiddin Dushanovich O`rinov Og`abek To`lqin o`g`li 3.Ichki ishlar Sektori Karmana tuman 7. 90-619-02-77 99-715-11-94 Narpay MFY Sh.Xolmurodov 97 3661912 4.Soliq sektori M.Baxrom MFY 8. N.Ergashev 90 6191715 Nurota tumani 1.Hokim sektori Nurota tuman Dehibaland 9. -

The Schroeder Institute in Uzbekistan: Breeding and Germplasm Collections

COVER STORY HORTSCIENCE 39(5):917–921. 2004. (Cannabis sativa L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), cereal crops, and forage crops. Later, separate research institutes were established to focus on The Schroeder Institute in Uzbekistan: individual crops and initiate specifi c breed- ing programs. TAES was the fi rst institute in Breeding and Germplasm Collections Central Asia established for studies of genet- ics/breeding and the cultural management of Mirmahsud M. Mirzaev and Uri M. Djavacynce fruits, grapes, and nuts. Richard R. Schroeder Uzbek Research Institute of Fruit Growing, Viticulture, and Schroeder developed improved cultivars of Wine Production, 700000 Tashkent, Glavpochta, ab #16, Republic of Uzbekistan cotton, rice, corn (Zea mays L.), and other crops (Schroeder, 1956). In tree fruits, he focused 1 2 David E. Zaurov, Joseph C. Goffreda, Thomas J. Orton, Edward G. on improving cold-hardiness, resistance to dis- Remmers, and C. Reed Funk eases and insects, and yield. In 1911, Schroeder Department of Plant Biology and Pathology, Cook College, Rutgers University, participated in the 7th International Congress New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8520 of Arid Lands in the United States for cotton and orchard crops. While in the United States, Additional index words. germplasm, apples, walnuts, peach, grapes, plums, almonds, he collected seeds of legumes, sorghum, and apricots, pistachios, breeding cotton cultivars and evaluated them in Central Asia. Shortly thereafter, Schroeder published Central Asia was largely isolated from the Uzbek Scientifi c Research Institute of Plant an agricultural monograph that was widely western world from the early 1800s until 1991, Industry (former branch of VIR) and Uzbek distributed throughout the Russian Empire and, when the former Soviet Union was dissolved.