Monograph Series, Pasi, Part V, Series-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

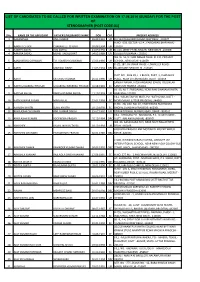

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge. -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Compliance Or Defiance? the Case of Dalits and Mahadalits

Kunnath, Compliance or defiance? COMPLIANCE OR DEFIANCE? THE CASE OF DALITS AND MAHADALITS GEORGE KUNNATH Introduction Dalits, who remain at the bottom of the Indian caste hierarchy, have resisted social and economic inequalities in various ways throughout their history.1 Their struggles have sometimes taken the form of the rejection of Hinduism in favour of other religions. Some Dalit groups have formed caste-based political parties and socio-religious movements to counter upper-caste domination. These caste-based organizations have been at the forefront of mobilizing Dalit communities in securing greater benefits from the Indian state’s affirmative action programmes. In recent times, Dalit organizations have also taken to international lobbying and networking to create wider platforms for the promotion of Dalit human rights and development. Along with protest against the caste system, Dalit history is also characterized by accommodation and compliance with Brahmanical values. The everyday Dalit world is replete with stories of Dalit communities consciously or unconsciously adopting upper-caste beliefs and practices. They seem to internalize the negative images and representations of themselves and their castes that are held and propagated by the dominant groups. Dalits are also internally divided by caste, with hierarchical rankings. They themselves thus often seem to reinforce and even reproduce the same system and norms that oppress them. This article engages with both compliance and defiance by Dalit communities. Both these concepts are central to any engagement with populations living in the context of oppression and inequality. Debates in gender studies, colonial histories and subaltern studies have engaged with the simultaneous existence of these contradictory processes. -

Vishnu's Crowded Temple

Vishnu’s Crowded Temple This page intentionally left blank MARIA MISRA Vishnu’s Crowded Temple India since the Great Rebellion Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. First published in the United Kingdom in 2007 by the Penguin Group. First published in the United States in 2008 by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2007 by Maria Misra. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in 10.5/14 pt PostScript Linotype Sabon by Rowland Phototypesetting Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2007936529 ISBN 978-0-300-13721-7 (cloth : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father, Manmohan Nath Misra, 1926–2006 . This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi Maps xii Introduction xxiii 1 Tropical Gothic 1 2 Babel-Mahal 47 3 Far Pavilions 102 4 Spinning the Nation 144 5 A House Divided 206 6 The Last Viceroy 259 7 Flames 311 8 Levelling the Temple 368 Epilogue, or Divine Developments 435 Glossary 451 Sources and Bibliography 456 Index 495 . -

100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities

100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities A Report Edited by John Dayal ISBN: 978-81-88833-35-1 Suggested Contribution : Rs 100 Published by Anhad INDIA HAS NO PLACE FOR HATE AND NEEDS NOT A TEN-YEAR MORATORIUM BUT AN END TO COMMUNAL AND TARGETTED VIOLENCE AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A report on the ground situation since the results of the General Elections were announced on16th May 2014 NEW DELHI, September 27th, 2014 The Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, led by Bharatiya Janata Party to a resounding victory in the general elections of 2014, riding a wave generated by his promise of “development” and assisted by a remarkable mass mobilization in one of the most politically surcharged electoral campaigns in the history of Independent India. When the results were announced on 16th May 2014, the BJP had won 280 of the 542 seats, with no party getting even the statutory 10 per cent of the seats to claim the position of Leader of the Opposition. The days, weeks and months since the historic victory, and his assuming ofice on 26th May 2014 as the 14th Prime Minister of India, have seen the rising pitch of a crescendo of hate speech against Muslims and Christians. Their identity derided,their patriotism scoffed at, their citizenship questioned, their faith mocked. The environment has degenerated into one of coercion, divisiveness, and suspicion. This has percolated to the small towns and villages or rural India, severing bonds forged in a dialogue of life over the centuries, shattering the harmony build around the messages of peace and brotherhood given us by the Suis and the men and women who led the Freedom Struggle under Mahatma Gandhi. -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

Indian Dalits and Hindutva Strategies Seth Schoenhaus Denison University

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 16 Article 1 2017 Indian Dalits and Hindutva Strategies Seth Schoenhaus Denison University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Schoenhaus, Seth (2017) "Indian Dalits and Hindutva Strategies," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 16 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol16/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Schoenhaus: Indian Dalits and <i>Hindutva</i> Strategies INDIAN DALITS AND HINDUTVA STRATEGIES Indian Dalits and Hindutva Strategies Seth Schoenhaus The Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, is a right-wing nationalist political party charged by its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Singh (RSS), to spread its ideology of Hindutva (Hindu nationalism) through the political process.1 In doing this, the BJP has gained national prominence, as seen most recently in its resounding 2014 victory in which Narendra Modi shot to power as Prime Minister of India.2 However, the party has made itself into the stalwart political arm of In- dia’s burgeoning middle class: conservative, fairly wealthy voters who tend to see themselves as the backbone of India’s emerging global might and economic prow- ess.3 In order to increase its share of power, the BJP and other Hindutva organiza- tions have increasingly realized the need to reach out to Scheduled Caste voters, specifically Dalits: those who have largely existed at the bottom of the Indian caste system, below even those considered “untouchable.”4 Dalits often find themselves on the fringe of acceptable Indian society due to their historically low caste posi- tion, so their receptiveness to Hindutva politics is quite curious. -

THE SCHEDULED CASTES and SCHEDULED TRIBES LISTS (L\Tiodl

lEltO ia EXTRAORDINARY PART II-Section 3 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY '1',1' ;::.-;:::.::.=:_-;::..==~=:':===---=====:_:':"":""--::::::'-:-':" . ----- ':=:=::'=:=.=,-=:::-'-:"'-':':=="::==-.=--';: =-=-:: :'.-=-==.:"-==-=.: -:.::;:.-.:':'="::"-=:=:--=:":':::":~~::':7=-:-':'-=-'=~,:.-. :=.:-_.~=:":' :=.:.. ,·;f~o.316-A] NEW DELHI, MONDAY, OCTOBER, 29, 1956 MINISTRY OF HOl\'IE AFFAIRS NOTIFICA TION New Del1ii, the 29th OctobeT 1956 S.R,O. 2477A.-The following Order made by the President is published Jorgeneral information:- ,:lTHE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES LISTS (l\tIODl . FICATION) ORDER, 1956 In pursuance of section 41 of the States Reorganisation Act, HI;)lj (.37 of1956) I and section 14 of the Bihar and West Bengal (Transfer of Terri tories) Act, 1956 (40 of 1956), the President hereby nlakes Lhe following Order, namely:- 1. This Order may be called the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes .,.Lists (Modification) Order, 1956. 2. (1) The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Or~er, 1950, is hereby modi .', nE'd in the manner and to the extent specified in Schedule I. ,3. (2) The Co.nstit~tion (Sch'eduled Castes) (Part C Sta~es) ~rd~eJ~,1951, 'IS hereby modIfied m the manner and to the extent specIfied m Schedule .II. ( 3, (1) The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, is herl"by modified in the manner and la the exLenL specified in Schedule lIT. , (2) The Constitution (ScheGuled Tribes) (Part C States) Order. 1:Fd, 'JJiS;', IV.hereby modified' in the manner and Lo the extent specified in Sc!.-,.·d·de SCHEDULE I [See pa~agr8ph 2(1)J J\lodifications to tlle Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order.. ) 950. 1. In pcuag1'8ph 2, for "Part5 I jo XVI", substitute "Parts I to XIII" ( 21(;1/1 ) '.