Origins of the Girmitiyas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

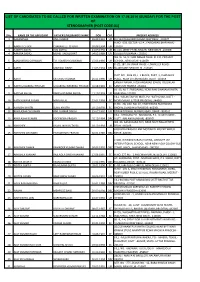

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

Uttar Pradesh.Xlsx

Uttar Pradesh Production Grant for the Group Dance S.no File No organisation Address unique ID project Deficiency Contact No. 1 UP(G)(D)1 Sanskritik Samajik Samiti Vill&Post-Tari Badagaon, Tehsil- UP/2013/0069255 Charon oor Gopiyan Beech Rasra, Distt. Ballia me Kanhaiya 2 UP(G)(D)2 Ravindranath Tagore Gramosthan Plot No.1, Hanumant Nagar, UP/2012/0052849 Avdhi Birha Karyakram ka evam Shiksha Prasar Sansthan Triveni Nagar-3, Near Neuton pradarshan Public School, Seetapur Road, Lucknow 3 UP(G)(D)3 Vaishali Kala Kendra C-36, Sector-56, NOIDA, Gautam UP/2012/0054234 Shakuntala Budh Nagar 4 UP(G)(D)4 Adarsh Aruna Vidya Mandir Vill&Post-Kothava, Dist-Hardoi UP/2013/0058995 Dance performance of Samiti Kathak 5 UP(G)(D)5 Pt. Ram Asare Mishra Shikshan Nagar Panchayat Koiripur, Dist UP/2014/0074197 Cultural programs Sansthan Sultanpur, UP 6 UP(G)(D)6 Gram Vikas Sansthan E-39, Shivani Vihar Kalyanpur, UP/2009/003312 Devbhoomi Uttarakhand Lucknow Ki Prernadeeya Paramparaon par acharit karyakram 7 UP(G)(D)7 Kalika Bindabeen Pramparik Village-Pure Raghav Pandir, Post- UP/2010/0037633 Kathak Natwari Kathak Natwari Lok Achalpur, District-Amethi 8 UP(G)(D)8 Ashok Evam Tripurari Maharaj Mo. Ram Nagar, Panchayat- UP/2010/0037669 Kathak Natya Shiksha Paramparik Kathak Natya Koiripur, Post-Koiripur, District- Sanskritik Kendra Sultanpur 9 UP(G)(D)9 Samanvaya, Sahitya, Samajik and 241, HIG, Ptam Nagar, Allahabad UP/2010/0035771 Antarik Lay Sansritik Sanstha 10 UP(G)(D)10 Gramin Mahila Kalyan Samiti village-Badodhi Post-Bharliya, UP/2010/0032261 Basti Mandal -

List of Villages [Below 2000 Population] Covered by Bank Through BC Model No

List of Villages [below 2000 population] covered by Bank through BC Model No. of S No. Zone Name of State District Name of Base Branch Name of village Population Household 1 AGARTALA MIZORAM AIZAWL AIZAWL ZOHMUN 1363 235 2 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR NINGTHOUKHONG AWANG 1540 181 3 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR SUNUSHIPHAI 1388 253 4 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR YUMNUM KHUNOU 1116 188 5 AGARTALA Tripura Khowai Baganbazar Halong matai 1485 348 6 AGARTALA Tripura Khowai Baganbazar Prem Sing Orang 1127 238 7 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Abdullapur 400 67 8 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Dulakandi 900 113 9 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Durgapur 1000 125 10 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur East Sakaibari 1180 135 11 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Kuterbasa 550 92 12 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Madhya Chandrapur 975 122 13 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Nathpara 900 112 14 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur North Chandra Pur 950 135 15 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Radhanagar 500 72 16 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur South Sakaibari 800 133 17 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Chandrapur 1050 150 18 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Raghna 600 86 19 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Sakai bari 1125 142 20 AGARTALA Tripura West Tripura Mohanpur Kambukcherra 1908 317 21 AHMEDABAD GUJARAT Amreli Amreli Bhutia 1800 40 22 AHMEDABAD GUJARAT Amreli Amreli Giria 1900 30 23 AHMEDABAD -

The Localization of Caste Politics in Uttar Pradesh After Mandal and Mandir

Institut d'études politiques de Paris ECOLE DOCTORALE DE SCIENCES PO Programme doctoral Science politique, mention Asie Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches Internationales (CERI) PhD in Political Science, specialization Asia The localization of caste politics in Uttar Pradesh after Mandal and Mandir Reconfiguration of identity politics and party-elite linkages Gilles Verniers Under the supervision of Christophe Jaffrelot, Directeur de recherche, CNRS-CERI Defended on December 16, 2016 Jury: Mrs Mukulika Banerjee, Associate Professor, London School of Economics and Political Science (rapporteure) Mr Christophe Jaffrelot, Directeur de recherche, CNRS-CERI Mr James Manor, emeritus Professor of Commonwealth studies and Senior Research fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies Mr Philip K. Oldenburg, Adjunct Associate Professor and Research Scholar, South Asia Institute, Columbia University Mrs Stéphanie Tawa Lama-Rewal, Directrice de recherche, CNRS-EHESS, CEIAS (rapporteure) Table of Contents List of Figures and Maps ................................................................................................................ 3 List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Form GST REG-06 Registration Certificate

Government of India Form GST REG-06 [See Rule 10(1)] Registration Certificate Registration Number :09AAACP0252G2ZQ 1. Legal Name POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD 2. Trade Name, if any M/S POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD 3. Constitution of Business Public Sector Undertaking 4. Address of Principal Place of 2nd , 3rd and 4th floor, 12, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Business Pradesh, 226001 5. Date of Liability 01/07/2017 6. Period of Validity From 01/07/2017 To NA 7. Type of Registration Regular 8. Particulars of Approving Authority Signature Name Designation Jurisdictional Office 9. Date of issue of Certificate 22/09/2017 Note: The registration certificate is required to be prominently displayed at all places of business in the State. This is a system generated digitally signed Registration Certificate issued based on the deemed approval of the application for registration Annexure A GSTIN 09AAACP0252G2ZQ Legal Name POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD Trade Name, if any M/S POWER GRID CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD Details of Additional Places of Business Total Number of Additional Places of Business in the State 47 Sr. No. Address 1 182, Parshwanath Panchwati, 1st and 2nd Floor, Agra- Lalitpur Consultancy Project Office, 100 Ft. Road, Fatehabad Road, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, 282001 2 Baghpat 400/220 KV GIS Sub Station, 5 KM Milestone, Baghpat - Saharanpur Road, Tyodi, Baghpat, Uttar Pradesh, 250611 3 303, 3rd, Chintel House, Station Road, Hussain Ganj, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, 227105 4 C-27/210A, Hindustan Times Campus, Aligarh House, -

Monograph Series, Pasi, Part V, Series-1

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY No.1: (No. 17 of 1961 Series) CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES I-INDIA MONOGRAPH SERIES PART V PASI (A Scheduled Caste in Uttar Pradesh) Field Investigation and Draft : H. N. SINGH Editing: H. L. HARIT, ~esearch (JJ?7cer N. O. NAG, Officer on Special Duty Consultant : B. K. Roy BURMAN, Deputy Registrar General OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS, NEW DE LID CONTENTS PAGE FOREWORD • • • • • • • • • • V PREFACE • • • • • • • • • • • vii Chapters : I Name, Identity, Origin and History • • 1·9 Affinity and sub~castes • • • • 3 History and migration • • • 8 H Distribution and Population Trend • • • • 10.13 Rural-urban distribution • • • • 12 Sex-ratio by broad age-groups • • 12 POPulation. trend • 13 III Physical Characteristics • • • • • 14 IV Family, Clan, I4inship and other Analogous Divisions • 15 V Dwelling, Dress, Food, Ornaments and other Material Objects distinctive of the Community • • • • 21 .. 23 Settlement and dwellings • • 21 Dress . • • • 22 Ornaments . • • 22 Tattooing • 22 Food' habits . 23 vt Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Disease and Treatment. • • • • • • • 25-27 Environmental sanitation and hygienic habits. 25 Disease and treatment • • • • • • • 25 VII Language and Education 28 .. 33 Language • • • 28 Literacy and Education • 28 VIII Economic Life 37.45 Working force • 37 Industrial classification of workers 39 t Agriculture • • 41 PAGE Agricultural labour 42 Pig and goat rearing 43 Qccup,.atio~ of ~igrapts 43 Qrimlq.al ac"tiviti~s in ~he tr~nsiti9nal ~eriog . 44 IX Life cycle • • • 48-61 Birth 48 Tonsure • • • 51 ~ar.boring ceremony 52 Sex taboos and marriage 52 Age at martiage 52 Marrl'age roles . 55 Mode of acquiring a mate 56 Consummation of marriage . -

A History of the East Indian Indentured Plantation Worker in Trinidad, 1845-1917

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 A History of the East Indian Indentured Plantation Worker in Trinidad, 1845-1917. John Allen Perry Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Perry, John Allen, "A History of the East Indian Indentured Plantation Worker in Trinidad, 1845-1917." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1612. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1612 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Tv-Aav PERRY, John Allen, 1S33- A HISTORY OF THE EAST INDIAN INDENTURED PLANTATION WORKER IN TRINIDAD, 1845 -1917. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © John Allen Perry 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A HISTORY OF THE EAST INDIAN INDENTURED PLANTATION WORKER IN TRINIDAD, 1845-1917 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Latin American Studies Institute by John Allen Perry B.S., California State Polytechnic College, 1959 B.S., Henderson State College, 1961 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1967 June, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost the writer would like to acknowledge his debt to Dr.