Reflections on the Mercury Music Prize in 2016, Simon Frith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

Laura Marling - Song for Our Daughter Episode 184

Song Exploder Laura Marling - Song For Our Daughter Episode 184 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Hrishikesh: Before we start, I want to mention that, in this episode, there’s some discussions of themes that might be difficult for some: sexual harassment and assault, as well as a mention of rape and suicide. Please use your best discretion. Laura Marling is a singer and songwriter from London. She won the Brit Award for Best British Female Solo Artist - she’s been nominated five times for that, along with the Mercury Prize, and the Grammy for Best Folk Album. Since 2008, she’s released seven albums. The most recent is called Song for Our Daughter. It’s also the name of the song that she takes apart in this episode. I spoke to Laura while she was in her home studio in London. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Laura: My name is Laura Marling. (Music fades out) Laura: This is the longest I've ever taken to write a record. You know, I started very young. I put out my first album when I was 17, and I'm now 30. When I was young, in a really wonderful way, and I think everybody experiences this when they're young, you're kind of a functioning narcissist [laughter], in that you have this experience of the world, in which you are the central character. -

Een Greep Uit De Cd-Releases 2012

Een greep uit de cd-releases 2012 Artiest/groep Titel 1 Aborted Global flatline 2 Allah -las Allah -las 3 Absynthe Minded As it ever was 4 Accept Stalingrad 5 Adrenaline Mob (Russel Allen & Mike Portnoy) Omerta 6 After All Dawn of the enforcer 7 Aimee Mann Charmer 8 Air La voyage dans la lune 9 Alabama Shakes Boys & girls 10 Alanis Morissette Havoc and bright lights 11 Alberta Cross Songs of Patience 12 Alicia Keys Girl on fire 13 Alt J An AwsoME Wave 14 Amadou & Mariam Folila 15 Amenra Mass V 16 Amos Lee As the crow flies -6 track EP- 17 Amy MacDonald Life in a beautiful light 18 Anathema Weather systems 19 Andrei Lugovski Incanto 20 Andy Burrows (Razorlight) Company 21 Angus Stone Broken brights 22 Animal Collective Centipede Hz 23 Anneke Van Giersbergen Everything is changing 24 Antony & The Johnsons Cut the world 25 Architects Daybreaker 26 Ariel Pink Haunted Graffitti 27 Arjen Anthony Lucassen Lost in the new real (2cd) 28 Arno Future vintage 29 Aroma Di Amore Samizdat 30 As I Lay Dying Awakened 31 Balthazar Rats 32 Band Of Horses Mirage rock 33 Band Of Skulls Sweet sour 34 Baroness Yellow & green 35 Bat For Lashes Haunted man 36 Beach Boys That's why god made the radio 37 Beach House Bloom 38 Believo ! Hard to Find 39 Ben Harper By my side 40 Berlaen De loatste man 41 Billy Talent Dead silence 42 Biohazard Reborn in defiance 43 Black Country Communion Afterglow 44 Blaudzun Heavy Flowers 45 Bloc Party Four 46 Blood Red Shoes In time to voices 47 Bob Dylan Tempest (cd/cd deluxe+book) 48 Bob Mould Silver age 49 Bobby Womack The Bravest -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

CST2110 Individual Programming Assignment #2 Deadline For

CST2110 Individual Programming Assignment #2 Deadline for submission 16:00, Friday 16rd April, 2021 Please read all the assignment specification carefully first, before asking your tutor any questions. General information You are required to submit your work via the dedicated Unihub assignment link in the ‘week 24’ folder by the specified deadline. This link will ‘timeout’ at the submission deadline. Your work will not be accepted as an email attachment if you miss this deadline. Therefore, you are strongly advised to allow plenty of time to upload your work prior to the deadline. Submission should comprise a single ‘ZIP’ file. This file should contain a separate, cleaned1, NetBeans project for each of the three tasks described below. The work will be compiled and run in a Windows environment, so it is strongly advised that you test your work in a Windows environment prior to cleaning and submission. When the ZIP file is extracted, there should be three folders (viewed in Windows explorer) representing three independent NetBeans projects as illustrated by Figure 1 below. Figure 1: When the ZIP file is extracted there should be three folders named Task1, Task2 and Task3 Accordingly, when loaded into NetBeans, each task must be a separate project as illustrated by Figure 2 below. Figure 2: Each task must be a separate NetBeans Project To make this easier, a template NetBeans project structure is provided for you to download. 1 In the NetBeans project navigator window, right-click on the project and select ‘clean’ from the drop-down menu. This will remove .class files and reduce the project file size for submission. -

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

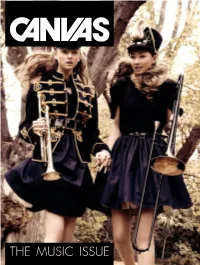

Canvas 06 Music.Pdf

THE MUSIC ISSUE ALTER I think I have a pretty cool job as and design, but we’ve bridged the editor of an online magazine but gap between the two by including PAGE 3 if I could choose my dream job some of our favourite bands and I’d be in a band. Can’t sing, can’t artists who are both musical and play any musical instrument, bar fashionable and creative. some basic work with a recorder, but it’s still a (pipe) dream of mine We have been very lucky to again DID I STEP ON YOUR TRUMPET? to be a front woman of some sort work with Nick Blair and Jason of pop/rock/indie group. Music is Henley for our editorials, and PAGE 7 important to me. Some of my best welcome contributing writer memories have been guided by a Seema Duggal to the Canvas song, a band, a concert. I team. I met my husband at Livid SHAKE THAT DEVIL Festival while watching Har Mar CATHERINE MCPHEE Superstar. We were recently EDITOR PAGE 13 married and are spending our honeymoon at the Meredith Music Festival. So it’s no surprise that sooner or later we put together a MUSIC issue for Canvas. THE HORRORS This issue’s theme is kind of a departure for us, considering we PAGE 21 tend to concentrate on fashion MISS FITZ PAGE 23 UNCOVERED PAGE 28 CREATIVE DIRECTOR/FOUNDER CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Catherine McPhee NICK BLAIR JASON HENLEY DESIGNER James Johnston COVER COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER EDITORIAL MANAGER PHOTOGRAPHY Nick Blair Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission by Canvas is strictly prohibited. -

Antony and the Johnsons Til Northside

2015-04-14 13:30 CEST Antony and the Johnsons til NorthSide Med tilføjelsen af i alt fem nye navne inklusive et fænomenalt nyt hovednavn, der laver en unik koncert sammen med Aarhus Symfoniorkester, er den endelige plakat klar til NorthSide 2015 Mange måneders hårdt arbejde er nu overstået, og resultatet præsenteres i dag i form af en plakat med 41 navne, der spænder fra legendariske Grace Jones, popsensationen Sam Smith, hiphop-kongerne Wu-Tang Clan, fænomenale Antony and the Johnsons sammen med Aarhus Symfoniorkester og det mest ønskede NorthSide-navn nogensinde – The Black Keys. Med offentliggørelsen af plakaten sættes de sidste fem navne på plakaten, og heriblandt finder man Antony and the Johnsons, der til lejligheden har allieret sig med Aarhus Symfoniorkester. Den unikke sanger Antony Hegarty har en kompromisløs og udfordrende karriere bag sig, hvor det Mercury Prize- vindende mesterværk ”I Am a Bird Now” og albummet ”Cut the World” står som højdepunkter. Sidstnævnte blev indspillet i 2011 sammen med DR UnderholdningsOrkestret til to roste koncerter i København, og denne fantastiske musik vil nu blive genskabt på NorthSide. Antony Hegarty får følgeskab af norske Emilie Nicolas, der har imponeret med hittet ”Pstereo” fra det forrygende debutalbum ”Like I’m A Warrior” samt de to danske navne S!vas og Rangleklods. S!vas har redefineret dansk hiphop og introduceret så mange nye ord til det danske sprog, at han sidste år blev hædret med GAFFAs Specialpris for sin banebrydende musik, og duoen Rangleklods er efter stribevis af koncerter på de største europæiske festivaler både klar med et nyt album og klar til at præsentere deres intelligente og nuancerede klubmusik på NorthSide. -

October 23, 1993 . 2.95, US 5, ECU 4

Volume 10 . Issue 43 . October 23, 1993 . 2.95, US 5, ECU 4 AmericanRadioHistory.Com START SPREADING THE NEWS. CHARLES AZNAVOUR you make me feel so young ANITA BAKER witchcraft TONY BENNETT "new york, new york" BONO i've got you under my skin NATALIE COLE they can't take that away from me Frank Sinatra returns to the recording studio for the -first time in fifteen years. And he's GLORIA ESTEFAN come rain or come shine come home to the label and studio that are synonymous with the most prolific years of ARETHA FRANKLIN his extraordinary career. what now my love KENNY G Capitol Records proudly releases DUETS. all the way/one for my baby Thirteen new recordings of timeless Sinatra (and one more for the road) classics featuring the master of popular song JULIO IGLESIAS in vocal harmony with some of the world's summer wind greatest artists. LIZA MINNELLI. i've got the world on a string Once again, Sinatra re -invents his legend, and unites the generation gap, with a year's CARLY SIMON guess i'll hang my tears out to dry/ end collection of songs that make the perfect in the wee small hours of the morning holiday gift for any music fan. BARBRA STREISAND i've got a crush on you It's the recording event of the decade. LUTHER VANDROSS So start spreading the news. the lady is a tramp Produced by Phil Ramone and Hank Kattaneo Executive Producer: Don Rubin Released on October 25th Management: Premier Artists Services Recorded July -August 1993 CD MC LP EMI ) AmericanRadioHistory.Com . -

Das Große Alan-Bangs-Nachtsession -Archiv Der

Das große Alan-Bangs-Nachtsession1-Archiv der FoA Alan Bangs hatte beim Bayerischen Rundfunk seit Februar 2000 einen besonderen Sendeplatz, an dem er eine zweistündige Sendung moderieren konnte: „Durch die Initiative von Walter Meier wurde Alan ständiger Gast DJ in den Nachtsession‘s, welche jeweils in der Nacht vom Freitag zum Samstag auf Bayern2 ausgestrahlt werden. Seine 1.Nachtsession war am 18.02.2000 und seit dieser ist er jeweils 3 bis 4mal pro Jahr zu hören – die letzte Sendung wurde am 1.12.2012 ausgestrahlt. Im Jahr 2001 gab es keine Nachtsession, 2002 und 2003 jeweils nur eine Sendung.“ (Zitat aus dem bearbeiteten Alan-Bangs-Wiki auf http://www.friendsofalan.de/alans-wiki/ Ab 2004 gab es dann bis zu vier Sendungen im Jahr, die letzte Sendung war am 1.12. 2010. Alan Bangs‘ Nachtsession- Sendungen wurden zeitweise mit Titeln oder Themen versehen, die auf der Webseite bei Bayern 2 erschienen. Dazu gab es teilweise einleitende Texte zusätzlich zu den Playlisten dieser Sendungen. Soweit diese (noch) recherchierbar waren, sind sie in dieses Archiv eingepflegt. Credits: Zusammengestellt durch FriendsofAlan (FoA) unter Auswertung von Internet- Quellen insbes. den auf den (vorübergehend) öffentlich zugänglichen Webseiten von Bayern 2 (s. die aktuelle Entwicklung dort im folgenden Kasten ) IN MEMORIUM AUCH DIESES SENDEFORMATS Nachtsession Der Letzte macht das Licht aus Nacht auf Donnerstag, 07.01.2016 - 00:05 bis 02:00 Uhr Bayern 2 Der Letzte macht das Licht aus Die finale Nachtsession mit den Pop-Toten von 2015 Mit Karl Bruckmaier Alle Jahre wieder kommt der Sensenmann - und heuer haut er die Sendereihe Nachtsession gleich mit um. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Where to Next? a Dynamic Model of User Preferences

Where To Next? A Dynamic Model of User Preferences Francesco Sanna Passino∗ Lucas Maystre Dmitrii Moor Imperial College London Spotify Spotify [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ashton Anderson† Mounia Lalmas University of Toronto Spotify [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION We consider the problem of predicting users’ preferences on on- Online platforms have transformed the way users access informa- line platforms. We build on recent findings suggesting that users’ tion, audio and video content, knowledge repositories, and much preferences change over time, and that helping users expand their more. Over three decades of research and practice have demon- horizons is important in ensuring that they stay engaged. Most strated that a) learning users’ preferences, and b) personalizing existing models of user preferences attempt to capture simulta- users’ experience to match these preferences is immensely valuable neous preferences: “Users who like 퐴 tend to like 퐵 as well”. In to increase engagement and satisfaction. To this end, recommender this paper, we argue that these models fail to anticipate changing systems have emerged as essential building blocks [3]. They help preferences. To overcome this issue, we seek to understand the users find their way through large collections of items and assist structure that underlies the evolution of user preferences. To this them in discovering new content. They typically build on user pref- end, we propose the Preference Transition Model (PTM), a dynamic erence models that exploit correlations across users’ preferences. model for user preferences towards classes of items. The model As an example within the music domain, if a user likes The Beatles, enables the estimation of transition probabilities between classes of that user might also like Simon & Garfunkel, because other users items over time, which can be used to estimate how users’ tastes are who listen to the former also listen to the latter.