Alexandria in the Time of Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

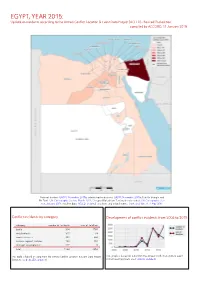

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

Egypt: Palestinian Pilgrims Stranded in Arish

Egypt: Palestinian DREF operation n° MDREG006 Pilgrims Stranded in 16 December 2008 Arish The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the International Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: CHF 150,000 (USD 129,650 or EUR 94,975) was allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 31 December 2007 to support the Egyptian Red Crescent (Egyptian RC) in delivering assistance to Palestinian pilgrims and to replenish disaster preparedness stocks. The first instalment of the DREF allocation was used to replenish the basic disaster preparedness stocks (relief items) of the Egyptian RC depleted to cover the immediate needs of the Palestinian pilgrims who were returning from pilgrimage and were stranded for days in the Egyptian Sinai. On 24 April, an extension of the timeframe of the operation was requested until the end of August 2008 based on the information given by the Egyptian RC and due to the repeated crises on the Egyptian borders. <click here for the final financial report, or here to view contact details> Map of Egypt showing El-Arish The situation Palestinian pilgrims returning from pilgrimage arrived in Egypt on 30 December 2007, mostly by ferries and through the Nuweiba port of the Red Sea. The pilgrims had planned to go back home through the Rafah border crossing point, which was the border used on their way to Mecca. -

Wadi AL-Arish, Sinai, Egypt

American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER 2017 American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) e-ISSN: 2320-0847 p-ISSN : 2320-0936 Volume-6, Issue-5, pp-172-181 www.ajer.org Research Paper Open Access Developing Flash Floods Inundation Maps Using Remote Sensing Data, a Case Study: Wadi AL-Arish, Sinai, Egypt 1 2 3 Mahmoud S. Farahat , A. M. Elmoustafa , A. A. Hasan 1Demonstrator, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. 2Associate Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, 3Professor of Environmental Hydrology, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt Abstract: Due to the importance of Sinai as one of the major development axes for the Egyptian government which try to increase/encourage the investment in this region of Egypt, the flood protection arise as a highly important issue due to the damage, danger and other hazards associated to it to human life, properties, and environment. Flash flood, occurred at the last fiveyears in different Egyptian cities, triggered the need of flood risk assessment study for areas highly affected by those floods. Among those areas, AL-Arish city was highly influenced and therefore need a great attention. AL-Arish city has been attacked by many floods at the last five years; these floods triggered the need of the evaluation flood risk, and an early warning system for the areas highly affected by those floods. The study aims to help in establishing a decision support system for the study area by determining the flood extent of wadiAL-Arish, so the damages and losses can be avoided, to reduce flood impact on the developed areas in and around wadi AL-Arish and to improve the flood management in this area in the future. -

The Egypt-Palestine/Israel Boundary: 1841-1992

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1992 The Egypt-Palestine/Israel boundary: 1841-1992 Thabit Abu-Rass University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1992 Thabit Abu-Rass Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Abu-Rass, Thabit, "The Egypt-Palestine/Israel boundary: 1841-1992" (1992). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 695. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/695 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EGYPT-PALESTINE/ISRAEL BOUNDARY: 1841-1992 An Abstract of a Thesis .Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the ~egree Master of Arts Thabit Abu-Rass University of Northern Iowa July 1992 ABSTRACT In 1841, with the involvement of European powers, the Ottoman Empire distinguished by Firman territory subject to a Khedive of Egypt from that subject more directly to Istanbul. With British pressure in 1906, a more formal boundary was established between Egypt and Ottoman Palestine. This study focuses on these events and on the history from 1841 to the present. The study area includes the Sinai peninsula and extends from the Suez Canal in the west to what is today southern Israel from Ashqelon on the Mediterranean to the southern shore of the Dead Sea in the east. -

A Death Foretold, P. 36

Pending Further Review One year of the church regularization committee A Death Foretold* An analysis of the targeted killing and forced displacement of Arish Coptic Christians First edition November 2018 Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 al Saray al Korbra St., Garden City, Al Qahirah, Egypt. Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 *The title of this report is inspired by Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981) Acknowledgements This report was written by Ishak Ibrahim, researcher and freedom of religion and belief officer, and Sherif Mohey El Din, researcher in Criminal Justice Unit at EIPR. Ahmed Mahrous, Monitoring and Documentation Officer, contributed to the annexes and to acquiring victim and eyewitness testimonials. Amr Abdel Rahman, head of the Civil Liberties unit, edited the report. Ahmed El Sheibini did the copyediting. TABLE OF CONTENTS: GENERAL BACKGROUND OF SECTARIAN ATTACKS ..................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND ON THE LEGAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT OF NORTH SINAI AND ITS PARTICULARS ............................................................................................................................................. 12 THE LEGAL SITUATION GOVERNING NORTH SINAI: FROM MILITARY COMMANDER DECREES -

? S 37/ Contract NEB-0042-C-00-1008-O0 January, 1982 AA1# 82-2

Submitted to: U.S. Agency for International Development Informal Housing in Egypt I ? S 37/ Contract NEB-0042-C-00-1008-O0 January, 1982 AA1# 82-2 Project Director: Stephen K. Mayo Field Director: Judith L. Katz Study Participants Abt Associates, Inc. Dames & Moore, Inc. GOHBPR Cambridge, Mass. (Center for International Dokki Development and Technology) Cairo, Egypt Cambridge, Mass. Project Directors Stephen K. Mayo Harry Garnett Mohamed Ramez Principal Investigators Stephen K. Mayo Harry Garnett Hamed Fahmy Stnff/Consultants Ahmad Shawqi Khallaf ** Joseph Friedman Lata Chatterjee Suzette Aziz Judith L. Katz Aziz Fathy Nahid Naja al-Abyari Safia Mohsen Atef Dabbour Clay Wescott Aza Eleish Donna S. Wirt Maha Farid Mohamed al-Gowhari** Lamya Hosny Rida Sayid Ibrahim** Nasamat Abdel Kader Sherif Kamel Mahmud Abd al-Mawgud Sherifa Medwar Ahmad al-Baz Mohamed** Leila Muharram Nura Fathy Abdul Rahman Ahmad Salah ** Hisham Sameh Hamdi Shaheen Ahmed Sa'ad Sheikh** Nabila Ahmed Zaki** Mahmud Ibrahim Mahmud Adib Mena ikha'el **Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. Raga'a Ail Savid TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Number Abstract v Acknowledgements vii List of Tables ix List of Figures xii Summary xv Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Study Design 5 2.1 Scanning Survey 5 2.2 Occupant Survey 6 2.3 In-Depth Interviews 12 Chapter 3: Growth and Change in Cairo and Beni Suef 15 Chapter 4: The Role of the Informal Sector 25 4.1 Factors Cor tributing to the Growth of Informal Housing 34 4.2 Subdivision 36 4.3 Factors Contributing to Illegal Subdivision -

THE MINIA UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY CENTER by Donna G

A CONCEPT PAPER: THE MINIA UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY CENTER by Donna G. Weisenborn Coordinator of Community Education Bozeman, Montana Public Schools Ray E. Weisenborn Associate Professor of Communication Montana State University A report submitted to U.S. AID-Cairo July, 1978 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................... RECOMMENDATIONS......................... 2 THE SCOPE OF HIGHER EDUCATION.......... ..................... 5 Figure I - "Egyptian University System - 1978". .......... 7 MINIA GOVERNORATE ........... ........................... .13 Figure 2 - "Minia Governorate: Marakiz and Geographics"......... 14 Figure 3 - "Minia Governorate Educational Levels and chools/Classes/Enroliments................... 17 MINIA UNIVERSITY ........... ........................... .18 TECHNICAL ANALYSIS ........... .......................... .20 Non-Formal Education in Support of Change Serving LDC Needs . 20 Figure 4 - "Formal and Non-Formal Cyclic Bipolarism of Education Systems' Affect on National Development"....... .......... .22 Figure 5 - "Comparison of Formal and NFE Cyclic Bipolarism and Maslow's Hierarchy of Human Needs"........ ............... 23 Minia University Social Development Center .... ............ .25 PROJECT GOAL ............ ............................. .. 31 PROJECT PURPOSE ........... ........................... .. 34 Center Development ........... ........................ .39 Project Design........... ........................... .40 Establish Priority Needs ......... ...................... .42 PROJECT INPUTS ........... -

A Practical Guide to Cairo and Its Environs

UC-NRLF $B m DES 14 CAIRO OF TO-DAY visitors, and must be considered as approxi The tariff for the whole day is 60 p. There is a special tariff for the foUowinf Single. Eetiini. Polo Ground (Ghezireh) 5 P. 15 P. 1 hour's A '„ Abbassieh Barracks 7 15 „ 1 » Citadel . V „ 15 „ 1 5) Ghezireh Eace-Stand (race days) . 10 „ 30 „ 3 5J Tombs of the Caliphs 10 „ 30 „ 3 » Museum . 10 „ 20 „ 2 5> Hehopolis . 20 „ 40 „ 2 3> Pyramids . 50 „ 77 „ 3 5> Bargaining is, however, advisable, as cab-driver wiU occasionally take less, es the visitor speaks Arabic. Donkeys.—A good way of getting about quarters of Cairo is to hire a donkey b;y (3 or 4 piastres), or by the day (10 to 12 the donkey-boy as a guide. These donke one of the recognised institutions of Ca: are a smart and intelligent set of lads, and very obliging and communicative. The playful habit of christening their donkey names of English celebrities, both male anc a somewhat equivocal compliment. Electric Tramway.—Four lines have opened : from the Citadel to the Railway ; PKACTICAL INFOKMATION 15 Citadel to Boulaq ; Eailway Station to Abbassieh Esbekiyeh to the Kbalig (opposite Eoda Island). Fares for the whole distance, 1 p. first, and 8 mill, second class, with a minimum charge of 6 and 4 mill, respectively. A line is being constructed to the Ghizeh Museum and the Pyramids. Saddle-horses.—The usual charge is 30 p. the half day and 50 p. the whole day. Carriages.—Victorias and dog- carts can be hired at the Cairo ofi&ce of the Mena House Hotel, or at Shepheard's or the Continental. -

Population Census and Land Surveys Under the Umayyads (41–132/661–750)1

Population Census and Land Surveys under the Umayyads 341 Population Census and Land Surveys under the Umayyads (41–132/661–750)1 Wa d a d al-Qadi (University of Chicago) For Gernot Rotter On his 65th Birthday Envy is not a very good thing. Yet envy is precisely what an early Islamicist feels when he reads Roger Bagnall and Bruce Frier’s The De- mography of Roman Egypt.2 These Roman historians had at their dis- posal over 300 original census returns/declarations preserved on papyrus and covering the period from 11/12 to 257/258 AD.3 Many of these returns 1) I would like to thank Jeremy Johns, Chase Robinson, Paul Cobb, and Law- rence Conrad for reading drafts of this paper and giving me valuable feedback. 2) Roger S. Bagnal and Bruce Frier, The Demography of Roman Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). 3) There are records of later censuses in Roman/Byzantine Egypt. We know of a call for a census by the “Prefect of Egypt” in 297 AD, but neither the prefect’s edict nor the breviary have survived; see Allen Chester Johnson and Louis West, Byzantine Egypt: Economic Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949) 259; Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 17, 20. Johnson and West also mention (p. 260) that we have records of a census of the rural population that was carried out in two places in 309 AD. The rule in Byzantine Egypt was that, for the purpose of tax col- lection, “a formal ‘house by house’ census was instituted at fourteen-year inter- vals, corresponding to the age of male majority. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970 El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd How to cite: El-Aal, Wassim A.E. -H. M. Abd (1977) Spatial patterns of population dynamics in Egypt, 1947-1970, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7971/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk SPATIAL PATTERNS OF POPULATION DYNAMICS , IN EGYPT, 1947-1970 VOLUME I by Wassim A.E.-H. M. Abd El-Aal, B.A., M.A. (Graduate Society) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences for the degree of Doctor of PhDlosophy Uru-vorsity of Dm n?n' A.TDI 1077 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged Professor J.