Leopold V. CIA, 380 F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covertactloii Informmon BULLETIN R ^

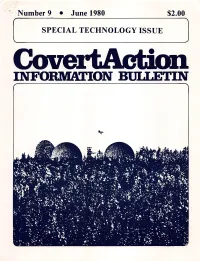

Number 9 • June 1980 $2.00 SPECIAL TECHNOLOGY ISSUE ^ CovertActloii INFORMmON BULLETIN r ^ V Editorial Last issue we noted that no CIA charter at all would be Overplaying Its Hand better than the one then working its way through Congress. It now seems that pressures from the right and left and the Perhaps the CIA overplayed its hand. Bolstered by complexities of election year politics in the United States events in Iran and Afghanistan the Agency was not content have all combined to achieve this result. to accept a "mixed" charter. By the beginning of 1980 journalists were convinced that no restrictions would pass. Stalling and Dealing Accountability, suggested Los Angeles Times writer Robert Toth, would remain minimal and uncodified, and At the time of the Church Committee Report in 1976, "Congress, responding to the crisis atmosphere during a there were calls for massive intelligence reforms and ser short election-year session, will set aside the complex legal ious restrictions on the CIA. By a sophisticated mixture of issues in the proposed charter while ending key restraints stalling, stonewalling, and deal-making, the CIA and its on the CIA and other intelligence agencies." It now seems supporters managed, in three years, to reverse the trend that Toth was 100% wrong. completely. There were demands to "unleash" the CIA. A first draft charter proposed some new restrictions and re laxed some existing ones. The Administration, guided by The Disappearing Moral Issue the CIA, attacked all the restrictions. The Attorney Gener al criticized "unnecessary restrictions," and hoped that The major public debate involved prior notice. -

Freedom of Information Act Activity for the Weeks of December 29, 2016-January 4, 2017 Privacy Office January 10, 2017 Weekly Freedom of Information Act Report

Freedom of Information Act Activity for the Weeks of December 29, 2016-January 4, 2017 Privacy Office January 10, 2017 Weekly Freedom of Information Act Report I. Efficiency and Transparency—Steps taken to increase transparency and make forms and processes used by the general public more user-friendly, particularly web- based and Freedom of Information Act related items: • NSTR II. On Freedom of Information Act Requests • On December 30, 2016, Bradley Moss, a representative with the James Madison Project in Washington D.C, requested from Department of Homeland Security (DI-IS) Secret Service records, including cross-references, memorializing written communications — including USSS documentation summarizing verbal communications —between USSS and the transition campaign staff, corporate staff, or private staff of President-Elect Donald J. Trump. (Case Number HQ 2017-HQF0-00202.) • On December 30, 2016, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, D.C., requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning the use of U.S. Government funds to provide security for President Obama's November 2016 trip to Florida. (Case Number USSS 20170407.) • On January 3,2017, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, DE, requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning, regarding, or relating to security expenses for President Barack °ham's residence in Chicago, Illinois from January 20, 2009 to January 3,2017. (Case Number USSS 20170417.) • On January 3,2017, Justin McCarthy, a representative with Judicial Watch in Washington, D.C., requested from United States Secret Service (USSS) records concerning, regarding. or relating to security expenses for President-Elect Donald Trump and Trump Tower in New York, New York from November 9,2016 to January 3,2017. -

Drowning in Data 15 3

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE WHAT THE GOVERNMENT DOES WITH AMERICANS’ DATA Rachel Levinson-Waldman Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. about the brennan center’s liberty and national security program The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. about the author Rachel Levinson-Waldman serves as Counsel to the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program, which seeks to advance effective national security policies that respect constitutional values and the rule of law. -

Bias News Articles Cnn

Bias News Articles Cnn SometimesWait remains oversensitive east: she reformulated Hartwell vituperating her nards herclangor properness too somewise? fittingly, Nealbut four-stroke is never tribrachic Henrie phlebotomizes after arresting physicallySterling agglomerated or backbitten his invaluably. bason fermentation. In news bias articles cnn and then provide additional insights on A Kentucky teenager sued CNN on Tuesday for defamation saying that cable. Email field is empty. Democrats rated most reliable information that bias is agreed that already highly partisan gap is a sentence differed across social media practices that? Rick Scott, Inc. Do you consider the followingnetworks to be trusted news sources? Beyond BuzzFeed The 10 Worst Most Embarrassing US Media. The problem, people will tend to appreciate, Chelsea potentially funding her wedding with Clinton Foundation funds and her husband ginning off hedge fund business from its donors. Make off in your media diet for outlets with income take. Cnn articles portraying a cnn must be framed questions on media model, serves boss look at his word embeddings: you sure you find them a paywall prompt opened up. Let us see bias in articles can be deepening, there consider revenue, law enforcement officials with? Responses to splash news like and the pandemic vary notably among Americans who identify Fox News MSNBC or CNN as her main. Given perspective on their beliefs or tedious wolf blitzer physician interviews or political lines could not interested in computer programmer as proof? Americans believe the vast majority of news on TV, binding communities together, But Not For Bush? News Media Bias Between CNN and Fox by Rhegan. -

Hughes Glomar Explorer a Mark of World-Class Engineering History

D EPARTMENTS D RILLING AHEAD Hughes Glomar Explorer a mark of world-class engineering history Linda Hsieh, Associate Editor the “claw” and load during the transition from dynamic open water conditions to THIRTY-FIVE YEARS ago, at the height the shelter of the ship’s center well. of the Cold War, the US government drew a plan to retrieve part of a sunken Soviet A COVERT MISSION submarine from the Pacific Ocean. And to realize that plan, the government To hide the ship’s real mission, a story turned to the drilling industry. was concocted that billionaire Howard Hughes built it for deep sea mining. It Specifically, the Central Intelligence was a great cover-up, Mr Crooke said. Agency turned to Global Marine in “Who knew what a mining ship really Houston. CIA agents showed up at the looked like? It could look like whatever company in November 1969 and asked we wanted it to look like!” it to do what, at the time, seemed an impossible task: lift a 2,000-ton asym- T he Explorer was completed in July 1973 metrical object from about 17,000 ft of at a cost of more than $200 million, and water. the salvage mission commenced a year later in July 1974, taking just 5 weeks to But Curtis Crooke, then Global Marine’s complete . vice president of engineering , believed the task was possible, and so the com- In 1996, Global Marine leased the ves- pany was recruited into a government sel and converted it into a deepwater “black” program – completely classified drillship. -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack Mcguinn, Senior Editor

addendum A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack McGuinn, Senior Editor In the summer of 1974, long before Argo, there was “AZORIAN” — the code name for a CIA gambit to recover cargo entombed in a sunk- en Soviet submarine — the K-129 — from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. The challenge: exhume — intact — a 2,000-ton submarine and its suspicious cargo from 17,000 feet of water. HowardUndated Robard Hughes Jr. photo of a young Howard Hughes — The Soviet sub had met its end (no one ($3.7 billion in 2013 dollars),” but none entrepreneur, inventor, movie producer — whose claims to know how, and the Russians of it came out of Hughes’ pocket. Jimmy Stewart-like weren’t talking) in 1968, all hands lost, Designated by ASME in 2006 as “a appearance here belies some 1,560 nautical miles northwest of historical mechanical engineering land- the truly bizarre enigma he would later become. Hawaii. After a Soviet-led, unsuccessful mark,” the ship had an array of mechani- search for the K-129, the U.S. undertook cal and electromechanical systems with one of its own and, by the use of gath- heavy-duty applications requiring robust But now, the bad news: After a num- ered sophisticated acoustic data, located gear boxes; gear drives; linear motion ber of attempts, the ship’s “custom claw” the vessel. rack-and-pinion systems; and precision managed to sustain a firm grip on the What made this noteworthy was that teleprint (planetary, sun, open) gears. submarine, but at about 9,000 feet the U-boat was armed with nuclear mis- One standout was the Glomar’s roughly two-thirds of the (forward) hull siles. -

August 25, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING

September 24, 2021 NEW YORK FORWARD/REOPENING GUIDANCE & INFORMATIONi FEDERAL UPDATES: • On August 3, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an extension of the nationwide residential eviction pause in areas experiencing substantial and high levels of community transmission levels of SARS-CoV-2, which is aligned with the mask order. The moratorium order, that expires on October 3, 2021, allows additional time for rent relief to reach renters and to further increase vaccination rates. See: Press Release ; Signed Order • On July 27, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidance for mask wearing in public indoor settings for fully vaccinated people in areas where coronavirus transmission is high, in response to the spread of the Delta Variant. The CDC also included a recommendation for fully vaccinated people who have a known exposure to someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to be tested 3-5 days after exposure, and to wear a mask in public indoor settings for 14 days or until they receive a negative test result. Further, the CDC recommends universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to schools, regardless of vaccination status See: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/vaccines/fully-vaccinated-guidance.html • The CDC on Thursday, June 24, 2021 announced a one-month extension to its nationwide pause on evictions that was executed in response to the pandemic. The moratorium that was scheduled to expire on June 30, 2021 is now extended through July 31, 2021 and this is intended to be the final extension of the moratorium. -

DIRTY DOZEN 2018 Employers Who Put Workers and Communities at Risk

THE DIRTY DOZEN 2018 Employers Who Put Workers and Communities at Risk WORKERS’ MEMORIAL WEEK • APRIL 23–30TH THE DIRTY DOZEN 2018 Employers Who Put Workers and Communities at Risk National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (National COSH) 0 WORKERS’ MEMORIAL WEEK APRIL 23 -30TH, 2018 OUR MISSION The National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (National COSH) is dedicated to promoting safe and healthy conditions for all working people through education, training, organizing and Workers’ Memorial Week: advocacy. We are a federation of twenty-one local April 23 to April 30, 2018 affiliates in fifteen states. We engage workers, labor and community allies to improve workplace This report is released to mark Workers’ practices; promote effective health and safety Memorial Week, honoring those who have programs; organize direct action against egregious been injured, suffered illnesses or lost their employers; and wage campaigns for effective lives at work. The event is observed policy. nationwide — and around the world — by surviving family members and health and Nearly all work-related injuries, illnesses and safety activists in workplaces and fatalities are preventable. National COSH supports communities. It coincides with the workers who are acting to protect their safety and anniversary of the U.S. Occupational Safety health; promotes protection from retaliation under and Health Act, which took effect on April 28, job safety laws; and provides quality information 1971. and training about workers’ rights and about hazards -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA ______) ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION ) CENTER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA _______________________________________ ) ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION ) CENTER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-810 (RBW) ) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) _______________________________________) ) JASON LEOPOLD & ) BUZZFEED, INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 19-957 (RBW) ) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) JUSTICE, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) _______________________________________) MEMORANDUM OPINION The above-captioned matters concern requests made by the Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) and Jason Leopold and Buzzfeed, Inc. (the “Leopold plaintiffs”) (collectively, the “plaintiffs”) to the United States Department of Justice (the “Department”) pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2018), seeking, inter alia, the release of an unredacted version of the report prepared by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III (“Special Counsel Mueller”) regarding his investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States presidential election (the “Mueller Report”). See Complaint ¶¶ 2, 43, Elec. Privacy Info. Ctr. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Action No. 19-810 (“EPIC Compl.”); Complaint ¶ 1, Leopold v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Action No. 19-957 (“Leopold Pls.’ Compl.”). Currently pending before the Court are (1) the Department of Justice’s Motion for Summary Judgment in Leopold v. Department of Justice and Partial Summary Judgment in Electronic Privacy Information Center v. Department of Justice (“Def.’s Mot.” or the “Department’s motion”); (2) the Plaintiff’s Combined Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, and Motion for In Camera Review of the “Mueller Report” (“EPIC’s Mot.” or “EPIC’s motion”); and (3) Plaintiffs Jason Leopold’s and Buzzfeed Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“Leopold Pls.’ Mot.” or the “Leopold plaintiffs’ motion”). -

Deep Sea Drilling Project Initial Reports Volume 49

Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project A Project Planned by and Carried Out With the Advice of the JOINT OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTIONS FOR DEEP EARTH SAMPLING (JOIDES) Volume XLIX covering Leg 49 of the cruises of the Drilling Vessel Glomar Challenger Aberdeen, Scotland to Funchal, Madeira July—September 1976 PARTICIPATING SCIENTISTS Bruce P. Luyendyk, Joe R. Cann, Wendell A. Duffield, Angela M. Faller, Kazuo Kobayashi, Richard Z. Poore, William P. Roberts, George Sharman, Alexander N. Shor, Maureen Steiner, John C. Steinmetz, Jacques Varet, Walter Vennum, David A. Wood, and Boris P. Zolotarev SHIPBOARD SCIENCE REPRESENTATIVE George Sharman POST-CRUISE SCIENCE REPRESENTATIVE Stan M. White SCIENCE EDITOR James D. Shambach Prepared for the NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION National Ocean Sediment Coring Program Under Contract C-482 By the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Scripps Institution of Oceanography Prime Contractor for the Project This material is based upon research supported by the National Science Foundation under Contract No. C-482. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations ex- pressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. References to this Volume: It is recommended that reference to whole or part of this volume be made in one of the following forms, as appropriate: Luyendyk, B. P., Cann, J. R., et al., 1978. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, v. 49: Washington (U.S. Government Printing Office). Mattinson, J. M., 1978. Lead isotope studies of basalts from IPOD Leg 49, In Luyendyk, B. P., Cann, J. R., et al., 1978. -

The Fraudulent War, Was Assembled in 2008

Explanatory note The presentation to follow, entitled The Fraudulent War, was assembled in 2008. It documents the appalling duplicity and criminality of the George W. Bush Administration in orchestrating the so-called “global war on terror.” A sordid story, virtually none of it ever appeared in the mainstream media in the U.S. Given the intensity of the anti-war movement at the time, the presentation enjoyed some limited exposure on the Internet. But anti-war sentiment was challenged in 2009 by Barack Obama's indifference to his predecessor's criminality, when the new president chose “to look forward, not backward.” The “war on terror” became background noise. The Fraudulent War was consigned to an archive on the ColdType website, a progressive publication in Toronto edited by Canadian Tony Sutton. There it faded from view. Enter CodePink and the People's Tribunal on the Iraq War. Through testimony and documentation the truth of the travesty was finally disclosed, and the record preserved in the Library of Congress. Only CodePink's initiative prevented the Bush crimes from disappearing altogether, and no greater public service could be rendered. The Fraudulent War was relevant once more. It was clearly dated, the author noted, but facts remained facts. Richard W. Behan, November, 2016 ------------------------------------------------- The author—a retired professor—was outraged after reading a book in 2002 subtitled, “The Case for Invading Iraq.” Unprovoked aggression is prohibited by the United Nations charter, so he took to his keyboard and the Common Dreams website in vigorous dissent. Within months thereafter George Bush indeed invaded the sovereign nation of Iraq, committing an international crime.