Signature Redacted for Privacy. Abstract Approved: David Brauner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

How to Identify Old Chinese Porcelain

mmmKimmmmmmKmi^:^ lOW-TO-IDENTIFY OLD -CHINESE - PORCELAIN - j?s> -ii-?.aaig3)g'ggg5y.jgafE>j*iAjeE5egasgsKgy3Si CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THE WASON CHINESE COLLECTION DATE DUE 1*-^'" """"^*^ NK 4565!h69" "-ibrary 3 1924 023 569 514 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023569514 'a4^(A<-^^ %//3 HOW TO IDENTIFY OLD CHINESE PORCELAIN PLATE r WHITE PORCELAIN "BLANC-DE-CHINE" PAIR OF BOWLS of pierced fret-work divided by five circular panels or medallions of raised figures in relief, supposed 10 represent the Pa-Sien or eight Immortals and the God of Longevity. Height, if in. Diameter, sfin. SEAL in the form of a cube surmounted by the figure of a lion Height, i^in. INCENSE BURNER, eight sided and ornamented by moulding in relief with eight feet and four handles. The sides have three bands enclosing scrolls in ancient bronze designs. At each angle of the cover is a knob; it is ornamented with iris and prunus, and by pierced spaces. The stand has eight feet and a knob at each angle ; in the centre is a flower surrounded by detached impressed scrolls, round the outside are similar panels to those on the bowl. Height, 4|in. Diameter of stand, 6f in. THE FIGURE OF A CRAB on a lotus leaf, the stem of which terminales in a flower. Length, 6| in. From Sir PV. fraiik^s Collection at the BritisJi Museum. S3 HOW TO IDENTIFY OLD CHINESE PORCELAIN BY MRS. -

Nature, Porcelain and the Age of the Enlightenment

Nature, Porcelain and the Age of the Enlightenment. A Natural History of Early English Porcelain and its place in the eighteenth century home. Paul Crane 92 The Age of Enlightenment in eighteenth century Europe established rules and rationalism in science and nature which swept aside the former superstitions and old medieval orders to highlight reality and learning within the educated classes. This in turn led to a fantasy of playful imagination that was to be the playground where Rococo design and form could firmly take root. Therefore just as Porcelain was a new European product and invention of the Enlightenment, it also became a substance with which modellers and designers, inspired by and developing the Rococo style, could play and entice. Europe in the mid eighteenth century was riveted by an insatiable appetite for knowledge, exploration and discovery. This forged a new scientific approach, which was to spearhead the Age of the Enlightenment. Through new eminent publications, science and nature became the pinnacle of taste and fashion amongst the aristocracy, who decorated their homes with this organic natural force of life. It is important to understand that the development of porcelain in England is directly inspired by a natural yearning to question and learn from the scientific breakthroughs and new understandings, which categorise this period of learning and discovery. the 5th March 1745 the Daily Advertiser stated that Exploration and science, both essentially funded by the ‘Chelsea China is arrived to such perfection, as to equal ruling classes now began to go hand in hand with new if not surpass the finest old Japan’1. -

Some Continental Influences on English Porcelain

52925_English_Ceramics_vol19_pt3_book:Layout 1 24/7/08 09:12 Page 429 Some Continental Influences on English Porcelain A paper read by Errol Manners at the Courtauld Institute on the 15th October 2005 INTRODUCTION Early French soft-paste porcelain The history of the ceramics of any country is one of We are fortunate in having an early report on Saint- continual influence and borrowing from others. In the Cloud by an Englishman well qualified to comment case of England, whole technologies, such as those of on ceramics, Dr. Martin Lister, who devoted three delftware and salt-glazed stoneware, came from the pages of his Journey to Paris in the year 1698 (published continent along with their well-established artistic in 1699) to his visit to the factory. Dr. Lister, a traditions. Here they evolved and grew with that physician and naturalist and vice-president of the uniquely English genius with which we are so Royal Society, had knowledge of ceramic methods, as familiar. This subject has been treated by others, he knew Francis Place, 2 a pioneer of salt-glazed notably T.H. Clarke; I will endeavour to not repeat stoneware, and reported on the production of the too much of their work. I propose to try to establish Elers 3 brothers’ red-wares in the Royal Society some of the evidence for the earliest occurrence of Philosophical Transactions of 1693. 4 various continental porcelains in England from Dr.. Lister states ‘I saw the Potterie of St.Clou documentary sources and from the evidence of the (sic), with which I was marvellously well pleased: for I porcelain itself. -

Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era

Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era Kin-Yee Ian Shin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Kin-Yee Ian Shin All rights reserved ABSTRACT -- Making “Chinese Art”: Knowledge and Authority in the Transpacific Progressive Era Kin-Yee Ian Shin This dissertation presents a cultural history of U.S.-China relations between 1876 and 1930 that analyzes the politics attending the formation of the category we call “Chinese art” in the United States today. Interest in the material and visual culture of China has influenced the development of American national identity and shaped perceptions of America’s place in the world since the colonial era. Turn-of-the-century anxieties about U.S.-China relations and geopolitics in the Pacific Ocean sparked new approaches to the collecting and study of Chinese art in the U.S. Proponents including Charles Freer, Langdon Warner, Frederick McCormick, and others championed the production of knowledge about Chinese art in the U.S. as a deterrent for a looming “civilizational clash.” Central to this flurry of activity were questions of epistemology and authority: among these approaches, whose conceptions and interpretations would prevail, and on what grounds? American collectors, dealers, and curators grappled with these questions by engaging not only with each other—oftentimes contentiously—but also with their counterparts in Europe, China, and Japan. Together they developed and debated transnational forms of expertise within museums, world’s fairs, commercial galleries, print publications, and educational institutes. -

China, China Export Porcelain, and the Construction of Orientalism During the American

The Lie In the Teapot: China, China Export Porcelain, and the Construction of Orientalism during the American Republic Kiersten Strachan Strachan 2 At the time of the American Revolution, China boasted a thriving economy and a booming population which was quadruple that of the United States. An elaborate welfare and taxation system, benchmarks the Constitutional Congress struggled to enact effectively, had been fully implemented by the time the first American trading ship reached China in 1783. However, the pervading narrative of China in the collective consciousness of citizens of the American Republic was that of an exotic fascination, instead of a developed nation-state. China was the subject of myth, having only ever been seen by a select and daring few, whose plunder and risk resulted in decadent spoils that adorned the homes of an exclusive American class. Of these spoils, Chinese porcelain was the most desired. Decorated with depictions of mountains, nature, delicate women and children, or intricate patterns, export porcelain was sometimes the only lens through which Americans formed their conceptions of China. A dangerous cyclical process emerged: the demand for typically ‘Chinese’ porcelain encouraged the production of essentializing depictions of Chinese culture. The increasing dispersion and popularity of this porcelain, in turn, reinforced the idea that China was static and undeveloped, confined to ceremony and the tradition of an Eastern empire. Rather than representing the start of a multifaceted relationship that led to cultural diffusion between America and China, the porcelain trade provided the basis for the misunderstanding of Chinese culture through essentialism and orientalism. This paper will substantiate the previous argument in four sections. -

Passion for Porcelain

A Passion for Porcelain Including The Paul and Helga Riley Collection The catalogue is dedicated to the memory of Helga Riley 15 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DB Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 6550 Fax: +44 (0)20 7389 6556 Email: [email protected] www.haughton.com All exhibits are for sale Foreword Foreword So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see and sharing conversations with like-minded collectors, museum curators and dealers, to finally contributing to ceramic So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. research, Paul has emerged from his pupae and has become as colourful a collector as one of his butterflies, William Shakespeare. Sonnet xviii. and a beacon to us all. We have also welcomed Paul and Helga many times here in the gallery, and usually, following a It is our privilege to introduce this catalogue dedicated to the memory of Helga Riley, who died in the autumn much discussed and well chosen purchase to fill a ‘gap’, we have all toddled round to one of the Clubs of 2008. She is sadly missed by all who knew and loved her. in Pall Mall to enjoy a leisurely fish lunch, and a chance to catch up on the latest news. Paul Riley, known to us all as Dr. Paul Riley, has become a towering figure in the annals of English The collection begins with a particularly fine Chelsea ‘Goat and Bee’ jug, No. 1, one of the finest and most tactile that Porcelain over the last fifty years, and needs no introduction to most of you who have read his intricate we have had the pleasure of handling. -

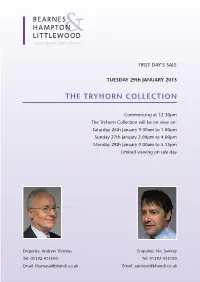

The Tryhorn Collection

FIRST DAY’S SALE TUESDAY 29th JANUARY 2013 THE TRYHORN COLLECTION Commencing at 12.30pm The Tryhorn Collection will be on view on: Saturday 26th January 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 27th January 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 28th January 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Tryhorn Collection The collection of the late Donald Tryhorn of Kingsbridge in Devon. Comprising 154 lots was accumulated with almost curatorial care over a period of 30 years. Although a private man, he was a regular face in both provincial and national auction rooms, indeed the collection includes a number of pieces acquired from the dispersal of other major collections. He was also an active buyer from many of the most recognised dealers of 18th century porcelain who no doubt will be keen to repatriate the odd ‘old friend’. He kept at least a dozen notebooks in which he recorded and cross referenced his acquisitions and in addition recorded the details of other pieces of interest that he had come across in salerooms but was unable to purchase at the time. These note and scrapbooks were almost constantly updated and annotated when new information came to light or when he perceived a previously overlooked characteristic. Donald Tryhorn’s collection has several main themes but primarily his passion was for Bow porcelain which is reflected in the fact that nearly a quarter of the lots in the collection are from that factory and range from simple tea bowls and large mugs through to desirable bottle vases. -

"The Coming Man from Canton": Chinese Experience in Montana (1862-1943)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2010 "The Coming Man From Canton": Chinese Experience in Montana (1862-1943) Christopher William Merritt The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merritt, Christopher William, ""The Coming Man From Canton": Chinese Experience in Montana (1862-1943)" (2010). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE COMING MAN FROM CANTON” CHINESE EXPRERIENCE IN MONTANA (1862-1943) By CHRISTOPHER WILLIAM MERRITT Master’s of Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, Michigan, 2006 Bachelor’s of Arts, The University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2004 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2010 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Dr. Kelly J. Dixon, Committee Chair Department of Anthropology Dr. John Douglas Department of Anthropology Dr. Richard Sattler Department of Anthropology Dr. Philip West The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Center Dr. Ellen Baumler Montana Historical Society Merritt, Christopher, Ph.D., May 2010 Cultural Heritage The Coming Man from Canton: Chinese Experience in Montana (1862-1943) Chairperson: Dr. -

The Roy Davids Collection of Chinese Ceramics Thursday 6 November 2014

the roy davids collection of chinese ceramics Thursday 6 November 2014 international chinese ceramics and works of art team Colin Sheaf Dessa Goddard Asaph Hyman asia and australia Xibo Wang Gigi Yu John Chong Shaune Kong Susie Quek Yvett Klein Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong Beijing Singapore Sydney europe Olivia Hamilton Sing Yan Choy James Hammond Rachel Hyman Rosangela Assennato Ben Law Smith Ian Glennie Asha Edwards London, London, London, London, London, London, Edinburgh Edinburgh New Bond Street New Bond Street Knightsbridge Knightsbridge Knightsbridge Knightsbridge USA Bruce MacLaren Nicholas Rice Edward Wilkinson* Mark Rasmussen* New York New York New York New York Henry Kleinhenz Daniel Herskee Andrew Lick Ling Shang Tiffany Chao San Francisco San Francisco San Francisco San Francisco Los Angeles asia representatives Hongyu Yu Summer Fang Bernadette Rankine Akiko Tsuchida Beijing Taipei Singapore Tokyo * Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art the roy davids collection of chinese ceramics Thursday 6 November 2014 at 10am 101 New Bond Street, London Lots 1 - 153 viewing enquiries customer services physical condition of Sunday 2 November 11.00 - 17.00 Colin Sheaf Monday to Friday 8.30 to 18.00 lots in this auction Monday 3 November 9.00 - 19.30 +44 (0) 20 7468 8237 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Tuesday 4 November 9.00 - 16.30 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS Wednesday 5 November 9.00 - 16.30 Please see page 4 for bidder NO REFERENCE IN THIS Asaph Hyman information including after-sale CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL sale number +44 (0) 20 7468 5888 collection and shipment CONDITION OF ANY LOT. -

Historical Archaeology of an Overseas Chinese Community In

AREA 2: 513/515 I STREET (FORMERLY 139/141 I STREET) Figure 18 is a plan view of the area after the excavation of Layer 954; Figure 19 is the Harris Matrix for these addresses; Figure 20 shows the cross section through the area after the excavation of Layer 954. SITE STRUCTURE Pier Bases After Context 976 and other demolition-associated contexts were cleared, 11 brick pier bases were exposed (Contexts 916, 921, 922, 923, 924, 925, 926, 927, 928, 929, 930). As these features were somewhat irregularly placed, it is unclear exactly how many buildings they represent. However, it seems likely that Contexts 923 through 930 were associated with a building toward the rear of the parcels, while the others are the remains of a second building that faced I Street. The pier bases ranged from 3 feet square to 3 feet 6 inches square and consisted of a series of stepped courses surmounted, in some cases, by the remnant of a brick pier 2 feet 6 inches square. Artifacts from the footing trenches did not provide tight dating evidence. However, the same lead water pipe that was found on 507 I Street also appeared on the present parcel. This pipe, designated Context 970, was clearly in place when the pier bases were constructed, whereas Wall 904 was constructed around the pipe. The footing trenches of all pier bases were excavated into Context 902, a layer of fine, yellow-brown, sandy silt. This stratum was from 2 to 8 inches in thickness and covered the entire area. It has an artifact-based TPQ of 1853 and appears to be an alluvium deposited by the flood of 1861-1862. -

Fine British Pottery & Porcelain

FINE BRITISH POTTERY & PORCELAIN Wednesday 12 November 2014 fine britiSh pottery & porCelain Wednesday 12 November 2014 at 14.00 101 New Bond Street, London Viewing bidS enquirieS CuStomer SerViCeS Sunday 9 November +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Fergus Gambon Monday to Friday 8.30 to 18.00 11:00 to 15:00 +44 (0) 20 7447 4401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8245 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Monday 10 Novemebr To bid via the internet please [email protected] 9:00 to 16:30 visit bonhams.com Please see page 4 for bidder John Sandon Tuesday 11 November information including after-sale +44 (0) 207 468 8244 9:00 to 16:30 Please note that bids should be collection and shipment submitted no later than 4pm on [email protected] Sale number the day prior to the sale. New James Peake important information bidders must also provide proof 21957 +44 (0) 207 468 8347 The United States Government of identity when submitting bids. [email protected] Failure to do this may result in has banned the import of ivory Catalogue your bid not being processed. [email protected] into the USA. Lots containing ivory are indicated by the £20.00 Telephone bidding European Ceramics symbol Ф printed beside the lot Bidding by telephone can only and Glass Department number in this catalogue. be accepted on lots with a low Simon Cottle estimate in excess of £1,000. +44 (0) 207 468 8383 [email protected] Live online bidding is Sebastian Kuhn available for this sale +44 (0) 20 7468 8384 Please email [email protected] with ‘live bidding’ in the subject [email protected] line 48 hours before the auction Nette Megens to register for this service +44 (0) 20 7468 8348 [email protected] Sophie von der Goltz +44 (0) 207 468 8349 [email protected] [email protected] Department Administrator Vanessa Howson +44 (0) 207 468 8243 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No.