The Mediated Ambiguities of the Syrian Nation State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

COUNCIL DECISION 2013/255/CFSP of 31 May 2013 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Syria

L 147/14 EN Official Journal of the European Union 1.6.2013 COUNCIL DECISION 2013/255/CFSP of 31 May 2013 concerning restrictive measures against Syria THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to (1) On 27 May 2013, the Council agreed to adopt for a determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. period of 12 months restrictive measures against Syria in the following fields, as specified in Council Decision 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning 2. It shall be prohibited to: restrictive measures against Syria ( 1): — export and import restrictions with the exception of arms and related material and equipment which (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering might be used for internal repression; services or other services related to the items referred to in paragraph 1 or related to the provision, manufacture, main — restrictions on financing of certain enterprises; tenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, Syria; — restrictions on infrastructure projects; — restrictions of financial support for trade; (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraph 1, — financial sector; including in particular grants, loans and export credit insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any — transport sector; sale, supply, transfer or export of such items, or for the provision of related technical assistance, brokering services or other services to any natural or legal person, entity or — restrictions on admission; body in, or for use in, Syria. -

Syria, a Country Study

Syria, a country study Federal Research Division Syria, a country study Table of Contents Syria, a country study...............................................................................................................................................1 Federal Research Division.............................................................................................................................2 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................5 Preface............................................................................................................................................................6 GEOGRAPHY...............................................................................................................................................7 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS....................................................................................8 NATIONAL SECURITY..............................................................................................................................9 MUSLIM EMPIRES....................................................................................................................................10 Succeeding Caliphates and Kingdoms.........................................................................................................11 Syria.............................................................................................................................................................12 -

The Road to Peace in the Balkans Is Paved with Bad Intentions

Pregledni rad Gregory R. Copley 1 UDK: 327.5(497) THE ROAD TO PEACE IN THE BALKANS IS PAVED WITH BAD INTENTIONS (An Address to the Conference on A Search for a Roadmap to Peace in the Balkans, organized by the Pan-Macedonian Association, Washington, DC, June 27, 2007) This conference is aptly titled “A Search for a Roadmap to Peace in the Balkans”, because we have yet to find a road map, let alone, should we find it, the right road to take. In any event, because of the short-term thinking, greed, fear, and ignorance which have plagued decision making with regard to the region by players inside it and out, the road to peace in the Balkans is paved with bad intentions. The short-term thinking, greed, fear, and ignorance have plagued decision making with regard to the region by players inside it and out. As a consequence, the road to peace in the Balkans is paved with bad intentions. It has been long and widely forecast that the security situation in the Balkans — indeed, in South-Eastern Europe generally — would become delicate, and would fracture, during the final stages of the Albanian quest for independence for the Serbian province of Kosovo and Metohija. As pessimistic as those forecasts were, however, the situation was considerably worsened by the eight-hour visit to Albania on June 10, 1 Gregory Copley is President of the International Strategic Studies Association (ISSA), based in Washington, DC, and also chairs the Association’s Balkans & Eastern Mediterranean Policy Council (BEMPC). He is also Editor of Defense & Foreign Affairs publications, and the Global Information System (GIS), a global intelligence service which provides strategic current intelligence to governments worldwide. -

The Middle East in International Relations Power, Politics and Ideology

This page intentionally left blank The Middle East in International Relations Power, Politics and Ideology The international relations of the Middle East have long been dominated by uncertainty and conflict. External intervention, interstate war, poli- tical upheaval and interethnic violence are compounded by the vagaries of oil prices and the claims of military, nationalist and religious move- ments. The purpose of this book is to set this region and its conflicts in context, providing on the one hand a historical introduction to its character and problems, and on the other a reasoned analysis of its politics. In an engagement with both the study of the Middle East and the theoretical analysis of international relations, the author, who is one of the best known and most authoritative scholars writing on the region today, offers a compelling and original interpretation. Written in a clear, accessible and interactive style, the book is designed for students, policy- makers and the general reader. is Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics. His publications include Nation and Religion in the Middle East (2000), Two Hours that Shook the World (2001) and 100 Myths about the Middle East (2005). The Contemporary Middle East 4 Series editor: Eugene L. Rogan Books published in The Contemporary Middle East series address the major political, economic and social debates facing the region today. Each title com- prises a survey of the available literature against the background of the author’s own critical interpretation which is designed to challenge and encourage indepen- dent analysis. While the focus of the series is the Middle East and North Africa, books are presented as aspects of a rounded treatment, which cut across disci- plinary and geographic boundaries. -

Owen Harris Hellenes and Arabs at Home and Abroad Greek

Hellenes and Arabs at Home and Abroad: Greek Orthodox Christians from Aleppo in Athens Owen Harris A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2021 Committee: Kathie Friedman Mary Kay Gugerty Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2021 Owen Harris University of Washington Abstract Hellenes and Arabs at Home and Abroad: Greek Orthodox Christians from Aleppo in Athens Owen Harris Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kathie Friedman Jackson School of International Studies Abstract: In this thesis, I show how communities living together in relative equality in Aleppo, Syria, and fleeing the same conflict, experienced very different outcomes depending on which religious community they belonged to. Members of the Greek Orthodox Christian community from Aleppo who have moved to Athens reported that their new home is exactly the same as the community they left behind. Members of the Muslim community from Aleppo in Athens did not agree with this statement. Why do Greek Orthodox Christians fare so much better than their Muslim compatriots in Greece? I argue that this inequality is a result of opportunities and challenges created by policies instituted during the great unmixing of peoples in the early 20th century and the refugee crisis in the early 21st century. Greek Orthodox Christians are equal citizens in a secular Arab republic that values ecumenism and members of the Greek diaspora in a Hellenic republic that privileges Greek ethno-religious belonging. They are Arab Hellenes, equally Greek and Syrian. Drawing on data collected in interviews with members of the Greek Orthodox Syrian community in Greece, as well as Syrians of different faiths in other countries, I examine what went right for Greek Orthodox Syrians in Athens and suggest policy tools that government and civil society can use to create similar conditions for Muslim Syrians in Greece. -

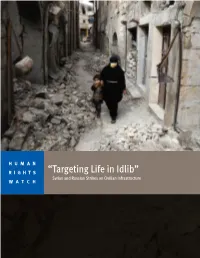

“Targeting Life in Idlib”

HUMAN RIGHTS “Targeting Life in Idlib” WATCH Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Map .................................................................................................................................. i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Arab Nationalism from a Historical Perspective: a Gradual Demise?

| 11 Yalova Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi Arab Nationalism from a Historical Perspective: A Gradual Demise? İsmail KURUN1 Abstract Arab nationalism emerged as a secular ideology in the early 20th century in the Ottoman Empire. During the First World War, it proved influential enough to motivate an Arab rebellion against the Ottomans and, following the war, several Arab states were founded. Its popularity rose in the interwar period, and many Arab mandates became independent after the Second World War. Its popularity peaked at the hands of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1958 when Syria and Egypt united to form the United Arab Republic. After the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Arab nationalism began losing its appeal and declined dramatically during the 1970s and 1980s. At the turn of the 21st century, Arab nationalism became an almost irrelevant ideology in the Middle East. This study examines the birth, the dramatic rise, and the sudden decline of Arab nationalism from a historical perspective and concludes that Arab nationalism today, as an ideology, is on the brink of demise. Keywords: political history;Arab nationalism; pan-Arabism; Islam Tarihsel Perspektiften Arap Milliyetçiliği: Tedrici Bir Ölüm Mü? Özet Arap milliyetçiliği 20. yüzyılın başlarında Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda seküler bir ideoloji olarak ortaya çıktı. Birinci Dünya Savaşı sırasında Osmanlılara karşı bir Arap ayaklanmasını motive edecek kadar etkili oldu ve savaştan sonra birkaç Arap devleti kuruldu. Arap milliyetçiliğinin popülaritesi iki savaş arası dönemde yükseldi ve birçok Arap devleti İkinci Dünya Savaşı’ndan sonra bağımsız hale geldiler. 1958’de Suriye ve Mısır, Birleşik Arap Cumhuriyeti’ni kurmak için birleştiklerinde Arap milliyetçiliğinin popülaritesi zirve yaptı. -

ARB 14 Syrie Yassin Haj Saleh

Arab Reform Brief June 14 2006 Political Reform and the Reconfiguration of National Identity in Syria Yasseen Haj-Saleh* Is it necessary for a conversation about cultural or social diversity in Levantine or Arab societies to be tied to another conversation about the disintegration of these societies and the risk of allowing powerful western powers a firm foothold in the area? Is there not a way to strengthen the unity and cohesiveness of these societies without dropping a wall of silence over the realities of diversity, all in the name of “national unity”? Could we not develop an approach that brings together these realities without camouflaging, exaggerating or down- playing their importance? Could we not place this approach within the context of a national democratic policy that guarantees equality and equal rights to all the country’s citizens regardless of their origin and background? Iraq’s current predicament is living proof that we need to transcend these ostrich-like policies as far as the social, cultural and religious make up of Arab societies are concerned. Syria cannot afford to be unconcerned by the ramifications of the long suppressed problems of diversity, especially given the intense and belligerent foreign presence in the region. Ever since the “oriental problem” surfaced, western presence in the region has traditionally been associated with the destabilisation of Levantine societies. Redefining the roots of Syrian national identity, as this paper argues, will end the risks of a possible resurgence of the oriental or the Greater Syria problems that operate under the old-new dilemma of “protecting minorities or spreading democracy.” The paper proposes the reconfiguration of the Syrian national identity based on an all- encompassing principle that considers Arabism as part of being Syrian, and one of the cornerstones of the democratic Syrian national identity. -

4457 Beamish.Pdf

R Beamish, David Thomas (2018) Intellectual currents and the practice of engagement : Ottoman and Algerian writers in a francophone milieu, 1890‐1914. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/26169 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Intellectual Currents and the Practice of Engagement: Ottoman and Algerian Writers in a Francophone Milieu, 1890-1914 David Thomas Beamish Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2017 Department of History SOAS, University of London Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Uncertain Refuge, Dangerous Return: Iraq's Uprooted Minorities

report Uncertain Refuge, Dangerous Return: Iraq’s Uprooted Minorities by Chris Chapman and Preti Taneja Three Mandaean men, in their late teens and early twenties, await their first baptism, an important and recurring rite in the Mandaean religion. The baptism took place in a stream on the edge of Lund, in southern Sweden. Andrew Tonn. Acknowledgements Preti Taneja is Commissioning Editor at MRG and the Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowledges author of MRG’s 2007 report on Iraq, Assimilation, Exodus, the following organizations for their financial contribution Eradication: Iraq’s Minority Communities since 2003. She towards the realization of this report: United Nations High also works as a journalist, editor and filmmaker specialising Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), The Ericson Trust, in human rights and development issues. Matrix Causes Fund, The Reuben Foundation Minority Rights Group International The authors would like to thank the following people: Abeer Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non- Dagestani, Salam Ghareb, Samira Hardo-Gharib, Kasem governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the Habib, Termida Salam Katia, Nuri Kino, Father Khalil, rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and Heatham Safo, Kate Washington, all those who contributed indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation their time, skills and insights and all those who shared their and understanding between communities. Our activities are experiences with us during the research for this report. focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and Report Editor: Carl Soderbergh. Production Coordinator: outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our Kristen Harrision. Copy Editor: Sophie Mayer. worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent minority and indigenous peoples.